Geography

Norway is flanked by Sweden to the east, by the Norwegian Sea to the west, by the Barents Sea to the north, and by the North Sea and the Skagerrak Strait to the south. Additional Norwegian territory includes Jan Mayen, a volcanic island; Svalbard, an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean; the unoccupied Bouvet island of the Atlantic Ocean; and Queen Maud Land in the Antarctic continent. About one-third of Norway lies north of the Arctic Circle. The country’s land area is 148,896 square miles. Norway’s terrain is generally mountainous; rolling hills and valleys are found in the east. Low plains make central Norway agriculturally important. To the south lie the Dovrefjell and Langfjell Mountain Ranges. Norway’s highest peak, Galdh0piggen (8,100 feet), is located in the Langfjell Mountains. To the west of the mountains lies Jostedalsbreen, Europe’s largest glacier field. Sognafjorden, situated along Norway’s west coastline, is the deepest and longest of the many fjords, about 5,000 feet deep and 127 miles long. Sharp plateaus, such as Dovrefjell, Hardangervidda, and Finnmarksvidde, rise up from the coast. The longest river, the Glama, and largest lake, Lake Mjosa, are both in the southeast.

INCEPTION AS A NATION

Norway was first united under King Harold I in about 900 C. E. during the age of the Vikings. However, the union dissolved by 940. Norway was not reunited until 1015 during the reign of Olaf ii, Harold’s son. in the late 13th century Norway gained control of Iceland. In 1397 Norway, Denmark, and Sweden joined under the Union of Kalmar. When Sweden pulled out of the union in 1523, Norway became a province of Denmark. Under Danish rule Norway lost Iceland to Sweden.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815) Denmark joined the French in a campaign against Britain. Upon defeat Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden (1814). Norway resisted this transfer and attempted to establish an independent government. The Swedish monarchy was forced on Norway, which was however, acknowledged as an independent kingdom in personal union with

NORWEGIANS:

NATIONALITY

Nation:

Norway; Kingdom of Norway (Kongeriket Norge)

Derivation of name:

From the old Norse root northrand veg, "northernway"; also rike, "kingdom"

Government:

Constitutional monarchy

Capital:

Oslo

Language:

Bokmal and Landsmal are two idioms of the official language Norwegian; Saami and Finnish are also spoken.

Religion:

About 86 percent of the population are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church; religious minorities include Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Muslims.

Earlier inhabitants:

Saami; tribal Germanics; Vikings

Demographics:

Ethnically people of Norway are homogeneous; several thousand Saami and Finns (some of them known as Kvens) make up the largest minority groups; others include Swedes, Danes, Americans, Pakistanis, Britons, Vietnamese, Chileans, and Iranians.

Sweden and allowed its own constitution and that status, Norway suffered from German legislature. occupation during World War II (1939-45) but

In 1905 Norway declared itself an inde - immediately restored its monarchy on Nazi pendent monarchy; Sweden soon recognized defeat in 1945.

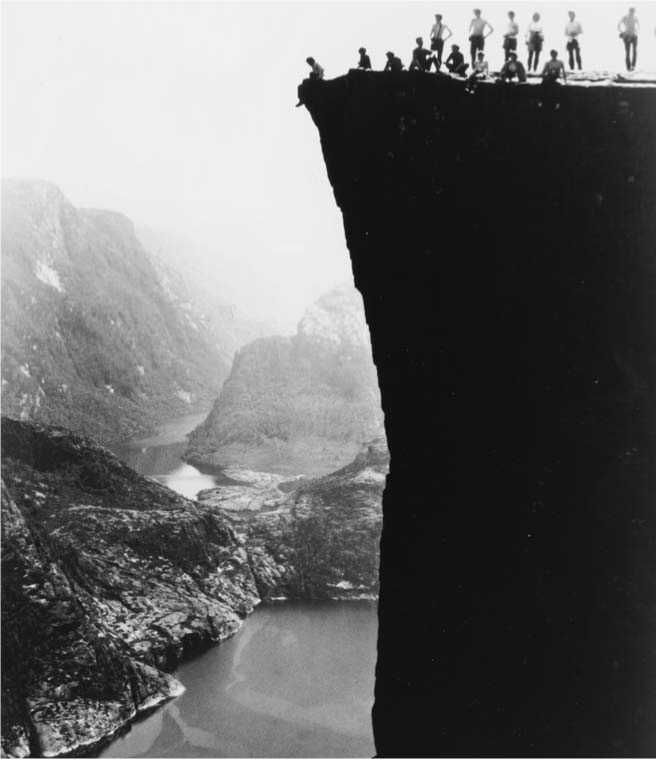

Norwegians stand atop Pulpit Rock near Stavanger at Norway's Lyse Fjord in the early 20th century. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-93696])

CULTURAL IDENTITY

Modern Norwegian cultural identity has been marked by the resurgence in interest in the culture of the ancestral Vikings and in folk music and art that began with the romantic nationalist movement of the latter 19th century. The composer Edvard Hagerup Grieg, with his evocative arrangements of Norwegian folk music both for piano and for orchestra, brought out a sense of the Norwegian national character, sometimes lusty and spirited, as in the Norwegian Dances, at others dour or wistful. Parts of the music of his Peer Gynt suite, for example, “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” evoke the dark underside of this northern people’s traditional belief in trolls and other malevolent spirits that haunt the long winter nights. This folk consciousness informed the planning of the entertainments during the Winter Olympics in Lilliehammer, which included an elaborate staging of a battle between spirit folk.

In the 20 th century Norwegian folk musicians have returned to the use of traditional instruments and styles, instead of adapting folk tunes to symphonic style. The so-called Hardanger fiddle (hardingfele) has been called the national instrument of Norway and provides an important focus for the revival of traditional music. Dating at least from the 17th century (and possibly earlier) the Hardanger fiddle differs from the violin primarily in having eight strings, four of which are not directly played but add sonority to the instrument through their sympathetic vibrations. It is used primarily for dance music. Many Norwegian folktales tell of fiddle players in communion with the supernatural, either receiving their powers from the spirit world or captured by trolls to perform for them.

Modern Norwegians have engaged in lively debate about what it means to be Norwegian. (Other groups, such as the Saami and Kvens, maintain their identity as minorities.) The stereotype—accepted by many Norwegians themselves—is that they are mainly a nation of fishermen and farmers who live close to nature and are simple, bucolic, gauche, and awkward when abroad among strangers or in cities. This is, of course, a vast oversimplification and largely untrue—many modern Norwegians are as cosmopolitan and urban as any other Europeans, and like other Europeans have been greatly influenced by American mass culture. They joke that the Norwegian national costume is not the bunader—finely embroidered red vests and white aprons for women and black jackets with green piping and pewter buttons and knee breeches for men—but blue jeans. Yet the myth persists of Norway as a country of people living and skiing in rural isolation amid dramatic fiords and great mountains.

There is some accuracy in the stereotype, at least in the recent past. Norway has had neither a strong landed gentry nor a solid urban bourgeoisie, and the vast majority of Norwegians were farmers or fishermen right up to the early 20th century. This has fostered a strong sense of individualism and egalitarianism and a dislike of central authority. Norwegian self-government is marked by the need for consensus and an ideology that demands a highly exacting degree of equality and fairness. The influence of these values on the administration of the Norwegian social welfare state, which temper its central planning aspect by giving due regard to the needs and priorities of localities, has caused analysts to consider it a laboratory for the future.

Some Norwegians point to the downside of being “farmers in the city”—of lacking a well-

See Ilmen Slavs.

Rooted urban culture and of having a fundamentally rural outlook on city life. Their compatriots, they say, tend to lack the flexibility, tolerance for difference, and perspective typical of city dwellers in other countries. The debate over “Norwegianness” includes a critique of the nationalistic version of recent history written by some Norwegian historians, especially Norway’s role in World War II. Overly glowing accounts of this role have succumbed to an uncritical and exaggerated patriotism strongly tainted with mythological and national ideology, skeptics say.

It is also pointed out that much of what is considered traditional Norwegian culture is really a construct by the urban bourgeoisie of the 19 th century, who hailed the culture of the mountain peasantry—in an idealized version—as the one true Norwegian cultural identity, ignoring the fact that the cultural identity of any people is constantly evolving through time.

Further Reading

Thomas Kingston Derry. A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1979).

-. A History of Modern Norway, 1814-1972

(Oxford: Oxford, 1973).

Knut Heidar. Norway: Center and Periphery (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 2000).

Byron S. Nordstrom. Dictionary of Scandinavian History (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1986). Arne Selbyg. Norway Today: An Introduction to Modern Norwegian Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987).

Frank Noel Stagg. South Norway (London: Allen & Unwin, 1958).

Janice S. Stewart. The Folk Arts of Norway (Rhinelander, Wis.: Nordhus, 1999).

World History

World History