Henry’s religiosity is best known from the elaborate provision which he made for the good of his soul after his death. His will, notoriously, requested 10,000 Masses for his soul. However, there was more to his relationship with the Church than this prodigious expenditure on somewhat mechanical and quantitative devotion. Henry was interested in the Church, as in so much else, primarily as a source of revenue. The ‘translation’ of bishops (that is, the transfer of a bishop from one diocese to another) was probably more widespread under this king than under any of his predecessors. The reason for this was not that he had strong and shifting views as to which churchman should serve which diocese, but that the royal prerogative included ‘regalian rights’ over Church property: during episcopal vacancies, the revenues of the diocese went to the king and incoming bishops were also mulcted for entry fines.

Besides that, the Church served as a source of reward for favoured servants and councillors. Episcopal appointments themselves were for the most part of trusted servants or their relatives. Stanleys and Audleys did pretty well on the basis of the political influence of their families, but without notably raising the intellectual or moral standards of the bench. James Stanley was made bishop of Ely for no better reason than that he was the stepson of the king’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort.

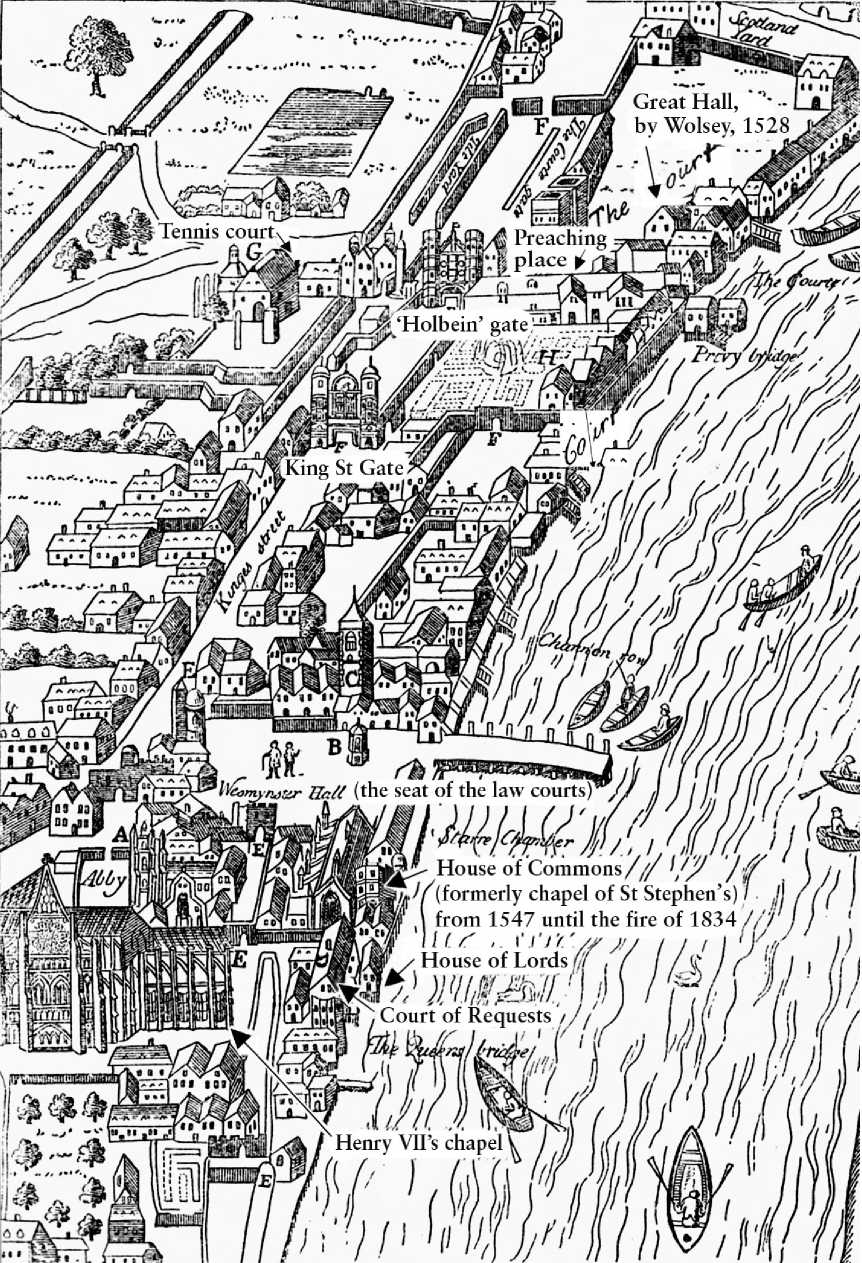

Plan of the palaces of Westminster and Whitehall, from a later version of the 1578 map known as Ralph Agas’s map (but not in fact by him). The Thames was in effect the main highway connecting London, Westminster, Lambeth, Southwark and Greenwich.

A hard-riding nobleman of the old school, he divided his time between the episcopal palace at Somersham, with his mistress and two children, and the family estates in Lancashire. His professional qualities are best summed up in the fact that we have no bishop’s register for his working career. Stanley, though, was something of an exception. Most of Henry’s bishops were hardworking, effective administrators, irrespective of whether their primary commitments were to Church or to Crown. John Morton, William Warham, Richard Fox, Thomas Ruthal, Oliver King, Richard Sherborne and the rest of the royal servants who were rewarded with bishoprics did not disgrace their calling, and one or two (such as Sherborne and Fox) proved, after their retirement from service at court, zealous and reform-minded pastors.

Henry’s rather cynical churchmanship should not be allowed to obscure his obviously genuine and entirely traditional piety. He showed consistent favour to the Observant Franciscans (that wing of the Franciscan friars which sought to revive strict observance of the original rule of St Francis), whom he may well first have come across during his years of exile in Brittany and France, where they were spreading rapidly in the later fifteenth century. In the first year of his reign he confirmed the recent foundation (1482) of an Observant house at Greenwich, and in 1500 founded another at Richmond, both of them beside his palaces - and the terms of his will show that he regarded both these houses as his own foundations. He also encouraged existing Franciscan houses to adopt the Observant lifestyle. In 1499, the Observants of England became a province of the order in their own right, numbering five houses by the time Henry died. Even after his death, his generosity continued, with substantial cash bequests made on behalf of the Observants in his will.

The piety of Henry VII was displayed in gestures which were made on a truly royal scale, but which were perfectly in tune with the devotional practices of his people. This entirely traditional piety was apparent in his attachment to the cult of the saints. After his victory at Stoke in 1487, Henry had donated a splendid votive statue of himself to the shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham, to which he had been on pilgrimage shortly before embarking on the military campaign of that year. Throughout his life he remained a devout and regular pilgrim. The shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury was a particular favourite, to which he returned frequently. In his will, he requested a statue identical to that which he had given to Walsingham to be made for the Canterbury shrine. Among Henry’s other favourite saints was the patron of England, St George. Louis XII of France, who conquered the Duchy of Milan around the turn of the century, found a relic of St George - a leg - among the booty of war. In due course this was sent to Henry as a present, and he was so pleased that on St George’s Day (23 April) 1505 he arranged and took part in a solemn procession which culminated in the public veneration of the relic, displayed for the purpose in St Paul’s Cathedral. In his will, Henry bequeathed the leg to the chapel royal of St George at Windsor.

Another of Henry’s works of devotion was the foundation in Westminster Abbey of a magnificent chantry chapel, the Lady Chapel, whose construction began in 1503. He intended it to house the shrine of his uncle, Henry VI (whose relics he planned

A view of Westminster, drawn by Anthony Van Wyngaerde, about 1550, from a collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Charing Cross, at the west end of the Strand, is among the landmarks clearly visible.

To transfer from Windsor to Westminster), as well as his own tomb. A third votive statue of the king was ordered in his will, to be donated to the shrine of St Edward the Confessor, which was also housed there. The chapel itself was glazed with splendid windows - sadly, long since destroyed - depicting scenes from the Bible. These windows were to serve as models for those which still survive in King’s College, Cambridge, and which, in their turn, give us a fair idea of what the glass in Henry’s chapel was like. The chapel at the back of the abbey church was to become, in effect, the Tudor mausoleum. All the Tudor monarchs apart from Henry VIII were to be laid to rest there.

Besides his foundation at Westminster, Henry founded the Savoy Hospital for the benefit of the London poor. His religious foundations sat squarely in the tradition of fifteenth-century English kingship. There was no sign in Henry of any humanist distaste for popular superstition and mechanical religion, still less of Reformation anxiety about the effectiveness of the Church’s intercession. But then Henry did not share his son’s passion for theology: his interest in religion was entirely practical - designed to get him into heaven, if only by the skin of his teeth. His reign saw the high tide of traditional piety in England, at least as far as it can be measured in material terms. Partly, no doubt, because his largely peaceful foreign policy minimised the fiscal burden on the population at large, expenditure on parish worship and on prayers for the dead reached record levels around 1500 (the costs of war followed by the onset of the English Reformation depressed the figures in his son’s reign). Henry played a full part in this movement, spending lavishly on the Church and on his own soul.

Henry’s piety, like that of many worldly Christians, was susceptible to dramatic intensification under tribulation or the threat of death. When he himself fell dangerously ill in 1504, one year after the death of his wife and two years after the death of his eldest son, he experienced a spiritual awakening. Repenting his ruthless fiscal exploitation of the Church, he vowed henceforth to appoint only worthy and devout men as bishops, making a fine start with his choice of John Fisher (spiritual director to Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort) as bishop of Rochester. As he put it in his letter to his mother, seeking her blessing for the promotion:

I have in my days promoted many a man unadvisedly, and I would now make some recompense

To promote some good and virtuous men, which I doubt not should please God.

Upon his recovery, however, the vow was forgotten, and as far as the episcopate was concerned it was business as usual. Church reform, like the crusade (to which Henry also paid lip service from time to time, especially in his declining years, when there was little prospect of his health permitting him to go on one), was something which everybody thought it would be a good idea for someone else to try. Five years later, on his deathbed, Henry recalled, or rather reiterated, his vow, promising that ‘the promotions of the church that were of his disposition should from henceforth be disposed to able men such as were virtuous and well learned’.

At a time when many of his subjects, especially the educated clergy, were keen to increase the quantity and quality of preaching available in the Church, Henry enjoyed a good sermon. Fisher was just one of many learned clerics from both Oxford and Cambridge who were summoned to court to edify their sovereign. And Henry’s chantry foundation in Westminster Abbey called for regular preaching by the learned monks both to their brethren and to the people. Not that he always took the spiritual admonitions of the Church too much to heart. Erasmus relates how a zealous friar preached censoriously before Henry VII on the vices of kings. Asked afterwards what he had made of it, Henry commented that putting that friar in the pulpit was rather like handing a naked blade to a madman. Nevertheless, it is plain from Henry’s immense provision for his soul after death that he was worried about what lay ahead, although not too much should be read into this. His provision for his soul represented a prodigious expenditure, but it was not disproportionate to the sort of amounts which the nobility and gentry were accustomed to devote to such purposes.

Henry’s increasingly frequent bouts of illness worsened early in 1509, and by March it was apparent that he was dying. He made his will on 31 March and died on 21 April in the palace he had built at Richmond. His agonies of conscience were reportedly intense, and his bodily agony more so. His only discernible achievement was to bequeath his throne to his son, and even that bequest looked distinctly shaky just five years before his death. Yet perhaps this was achievement enough. His three immediate predecessors had failed in this, the prime responsibility of the royal father, whatever other successes they might have enjoyed. And the throne that Henry bequeathed to his second son was more secure than it had been for a century at least. Luck there still was aplenty. King Arthur might have found his younger brother Henry rather a handful, and not even Henry VII’s notorious disinclination to dissipate the Crown lands and establish magnates had prevented him from equipping Prince Henry with a substantial apanage in Arthur’s lifetime. When Arthur died, Prince Henry’s lands as Duke of York were as yet worth less than ?i, ooo a year, but it is hard to believe that his father would not in due course at least have elevated him above the wealthiest nobleman in the country (the Duke of Buckingham). Henry of York might well have turned out as dangerous as Richard of York before him.

John Fisher, the most accomplished preacher among the bishops, was the obvious choice to preach the sermon at Henry’s funeral. There were the inevitable passages of eulogy. Fisher summarised Henry’s kingly virtues even while dismissing them as ‘vain transitory things’:

His politic wisdom in governance it was singular, his wit always quick and ready, his reason pithy and substantial, his memory fresh and holding, his experience notable, his counsels fortunate and taken by wise deliberation, his speech gracious in diverse languages, his person goodly and amiable, his natural complexion of the purest mixture, his issue fair and in good number, leagues and confederacies he had with all Christian princes, his mighty power was dread everywhere, not only within his realm, but without also.

There is little to quarrel with in this assessment. Yet his sermon was not just the usual encomium. Fisher also emphasised Henry’s repentance as death approached, recalling his promise to undertake ‘a true reformation of all them that were officers and ministers of his laws to the intent that justice from henceforward truly and indifferently might be executed in all causes’, and his forlorn vow that ‘if it pleased God to send him life they should see him a new changed man’. There is a passion about his call to his audience to assist their late sovereign with their prayers which leaves the unmistakable sense that Fisher really felt they were needed. A few months later he was called upon to preach in memory of the king’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, and the difference between the two sermons is striking. Whereas that on Lady Margaret is practically a case for canonisation, that on Henry is a meditation on the mysterious and wonderful mercy of God. Fisher is confident that Henry’s soul is safe, yet it is clearly the salvation of a repentant thief rather than a royal road to heaven that he presents to his listeners and readers. Fisher’s Lady Margaret is a model of sanctity; his Henry VII an object lesson in penitence. For all his own admiration for and gratitude to the king, Fisher knew how few there were who were really sorry to see him go:

Ah, King Henry, King Henry, if thou were alive again, many one that is here present now would pretend a full great pity and tenderness upon thee!

World History

World History