Jose de Hermosilla was undoubtedly aware of the delicate predicament he was entering when he accepted the commission to complete the interiors of Santissima Trinita, and it is also likely that he found the case against Rodriguez Dos Santos extremely disconcerting. The commission to work on a notable building site in Rome alongside some of the most important architects in the city was an opportunity that no Spaniard before him had ever experienced. The conflict Hermosilla faced was that, as a devoted pupil of Fuga, he felt compelled to agree with his master’s criticisms of Rodriguez Dos Santos’ scheme. His description of the Portuguese architect’s shortcomings - both in his report of 1749 and his subsequent treatise Architectura civil (Hermosilla y Sandoval 1750: 113) - confirmed his belief that Fuga’s criticisms were for the most part fair and accurate. Yet, at the same time, Hermosilla was like Rodriguez Dos Santos, a stranger in Rome having arrived there to establish himself as a critically independent architect. His reaction to the treatment Rodriguez Dos Santos received was likely tinged with sympathy, for he surely knew that the power wielded by the various architects and giudici was enough to damage one’s personal reputation - if not career - permanently. Therefore, it is not surprising to find that when Hermosilla was appointed as the architect in charge of Santissima Trinita, he would only trust Roman precedent or proven authority.

Following his appointment, Hermosilla and Father Alonso Cano assembled a team of artists and craftsmen who were not only capable of carrying out their respective commissions but also were ready to modify and improve The existing structure (Hermosilla y Sandoval 1750: 113). The ornamental work and plastering of the church interior commenced on June 5, 1748, and continued through the summer months.14 UNder the direction of Hermosilla, Baldassare Mattei carried out much of the stucco work in general, Antonio Cervoni was responsible for gilding, Domenico Palacios completed the decoration of the main vault, Pedro Bernabe was responsible for the decorative work in the sotto-choir narthex, and Pietro Pacilli carved the coats of arms (Villarroel 1998: 282-3). As noted by Elisa Debenedetti (2001b: 60-1), the expense books of the Trinitarian archive show, however, that in 1749 Pietro Pacilli received more than 2,000 scudi for statuary work at Santissima Trinita. This would have included the sculpture group framing the main arch of the sanctuary and crowning the retable of the high altar, and sculpture work in general for all the lateral chapels, making him the most important figure in the church’s plastic ornamentation. Although Hermosilla’s name is not recorded in the expense books of the Trinitarians, from June 1748 through December of the followinG year, annual payments, as well as gifts of chocolate, tobacco, and silk handkerchiefs, were given to the architect in charge of the work.15

To complete the interior, Hermosilla removed the lanterns in the main vault and rendered the surface with a combination of eight decorative ribs and basket weave coffers (a canestro), creating perhaps the most striking surface treatment of any Roman vault to date. As noted by Manfredo Tafuri (1964: 11-12), the basket-weave coffering must have been inspired by Fuga’s diamond-shaped coffers in the dome of Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte, though Fuga also used them to articulate the barrel vault of the new portico for the church of Santa Maria Maggiore (1741-43), and the cappella mag-giore of Sant’Apollinare (1742-48). The French architect, Antoine Deriset, decorated the interior of San Luigi dei Francesi (1749-53) with a similar treatment as well. Hermosilla would have also been familiar with the rich decorative treatment that graced the Mozarabic structures in southern Spain, as well as the more recent Baroque architecture of Seville and his hometown Llerena, where such latticework (cesteria) was quite common. Though Hermosilla was responsible for the rich surface treatment of the interior, the full stucco work was not completed until 1767 when the vault was gilded and the pilasters marbleized to celebrate the beatification of Fr. Simon de Rojas (Mancini 1997: II, 163-4).

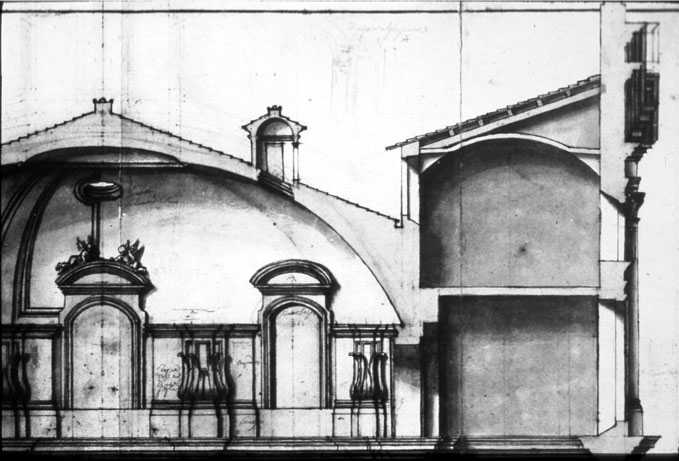

Hermosilla nevertheless increased the oval panel in the center of the dome so that Gregorio Guglielmi’s fresco of the Allegory of the Trinitarian Order (1748-49) could occupy a more prominent position within the dynamic space (Barroero 1990: 404-6; Barreda 2009: 69-70).16 Guglielmi, a Roman painter, had studied under Sebastiano Conca and in 1741 was appointed accademico di merito by the Accademia di San Luca, making him an ideal candidate to paint the central panel.17 HIs image depicts the vision of St. John of Matha, in which the Virgin appears in white, alongside two angels holding the cross and another angel below bearing the chains of a captive Christian slave (Figure 5.16). Previously, Guglielmi had executed a fresco of St. Ambrose with the Founders oF the Trinitarian Order (Figure 5.17) for the Sacristy vault (Barreda 2009: 69-70).18 GUglielmi would finish his work at Santissima Trinita in 1749 painting the fresco of the Apparition of the Virgin and Angels to Felix of Valois Above the choir vault (Barreda 2009: 71-2). Remarkably, Hermosilla’s interventions to the main space were noted on Rodriguez Dos Santos’ original drawings (Figure 5.18).19 Specifically, he indicated in free-hand that only the lanterns should be removed (levati solamente) and that the rest of the covering should remain intact. Hermosilla also noted in his Architectura civil that there was no need to carry out any further structural alterations to the vault, though he did provide a secondary layer of roof tiles over the exterior to prevent any further water infiltration (Hermosilla y Sandoval 1750: 113-14).

Hermosilla modified the attic story beneath the dome as well, and here his efforts were also noted on Rodriguez Dos Santos’ drawing. The upper right hand corner of the interior section contains a pencil sketch of the proposed new attic-story window, a rectangular opening capped by a semi-circular arch. The aedicule windows in Rodriguez Dos Santos’ section all have the letter “A” inscribed in pencil on their pediments, accompanied by the words tutto sesto on the further-most window on the right, suggesting that all of the attic-story

Figure 5.16 Gregorio Guglielmi, Allegory of the Trinitarian Order, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. BHR, bhpr32831a.

Figure 5.17 Gregorio Guglielmi, St. Ambrose with the Founders of the Trinitarian Order, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. BHR: bhpr32830a.

Windows were to be replaced by the one shown in the pencil sketch. For the six side chapels, Hermosilla produced a number of creative variations on the altar/retable motif (Figure 5.19). In all of these, aedicule surrounds framed the painted central panels, and statuary groups provided further sculptural effect. The chapels were further articulated with diamond shaped coffers on the central chapels and small ribbed domes on the diagonal ones (Figure 5.20). The arches separating the lateral chapels from the main body of the church were treated with shallow coffers. Hermosilla also designed all of the prayer rails that were carved by Francesco Cerrotti (Villarroel 1998: 284).

Hermosilla was also responsible for the scenic decoration of the main sanctuary with its monumental retable framing the high altar. As already noted, Pietro Pacilli carved the two angels atop the retable, and the celebrated Neapolitan painter, Corrado Giaquinto (1703-65), was commissioned to produce an altarpiece (Figure 5.21) with an image of The Holy Trinity Liberating a Christian Slave (Briganti 1990: I, 404 ff.). Giaquinto would eventually move to Spain in 1753 to assume the post of primer pintor del rey to Ferdinand VI (Perez Sanchez 2006). Around the same time, the Spanish artist, Antonio Gonzalez Velazquez, completed the paintings of the dome and pendentives above the main sanctuary (Figure 5.22), representing Abraham and the Three Angels and Moses and Three Other Prophets (Rius 1968; Urrea Fernandez 2006: 175-9). After training in Madrid at the drawing school of the Junta preparatoria of the Real Academia de San Fernando, he obtained a grant to

Figure 5.19 Side chapel with Gaetano Lapis’ St. John of Matha, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. Photo by author.

Figure 5.20 Max Hutzel, side chapel, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. © J. Paul Getty Trust. GRI 86.P.8.

Figure 5.22 Antonio Gonzalez Velazquez, Abraham and the Three Angels and Moses and Three Other Prophets, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. Photo by author.

Study in Rome in 1746, and he stayed there until 1752, working in the studio of Giaquinto. In 1748 he executed a canvas of the Good Shepherd for the entry chapel of the church, and portraits of Pope Innocent III Recognizing the Trinitarian Order, and The Two Founders of the Trinitarian Order for the chancel walls. To accommodate these works, Hermosilla removed the central pilasters along the lateral sides (the words deve levarsi can be found inscribed on Rodriguez Dos Santos’ drawing), and the central rib in the cupola (which had the word levato stamped on it). Additionally, the lunettes between the pendentives were articulated with coffered bands providing the space with a much more sculptural and scenic effect that contrasted beautifully with the basket weave treatment of the main vault.20

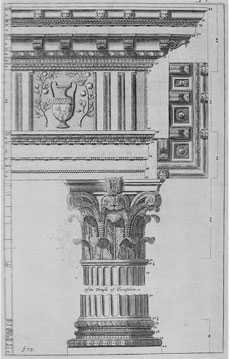

The chancel was undoubtedly the most important space in the church with its monumental retable whose columns resembled the “Order of Orders” from Villalpando’s reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (Figure 5.23). The two Corinthian columns - both semi-engaged, fluted and gilded - were set slightly on the diagonal to enhance the drama of Corrado Giaquinto’s painting of The Holy Trinity. More importantly, the two columns supported a frieze that was painted with floral garlands suspended in such a way that they appear to be defining a series of Doric triglyphs, like Villalpando’s order. Additionally, the frieze was arched between the two columns, with the triglyphs simply following the curve, a motif similarly

Figure 5.23 Juan Bautista Villalpando, the “Order of Orders” from Roland Freart, A Parallel of the Ancient Architecture with the Modern (1733). © Heidelberg University Library. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Employed on the interior of the church of Nuestra Senora de la Granada in Llerena (Figure 5.24). Certainly, by the middle decades of the eighteenth-century, the motif was well-known and much used, though the repetition of

Figure 5.24 Jose de Hermosilla, interior, Nuestra Senora de la Granada, Llerena. Photo by author.

The exact same version in both Rome and Llerena clearly points to Hermosilla’s involvement. To complete the retable, Hermosilla articulated the lunette above with a gilded sunburst and symbol of the Holy Trinity in the center, all surrounded by putti, a motif clearly inspired by Bernini’s Cathedra at Saint Peter’s.

Finally, Hermosilla altered the sotto-choir vestibule by refining the arched balcony that divided the two levels, introducing two Ionic columns (from Michelangelo’s Palazzo dei Conservatori) to soften the transition from major to minor order. Hermosilla further refined the balcony with an elaborate cartouche celebrating the Jubilee year of 1750, when the structure was finally completed. When seen from the nave, the arched opening and balcony perfectly frame Gregorio Guglielmi’s fresco of the Apparition of the Virgin atop the choir vault (Figure 5.25). Though modest in scope, all of these designs and alterations provided Hermosilla with the perfect opportunity to fulfill many of his architectural ambitions in Rome.

Among the important altarpieces commissioned for the church was the Immaculate Conception (1750) for the first chapel to the left of the high altar (Figure 5.26), by Francisco Preciado de la Vega (Cornudella i Carre 1997: 109-10). His painting touched upon a theme of unsurpassed importance to artists from Seville (Brown 1998: 222-3). Dispute of the Virgin’s immaculacy had divided the church since at least the Renaissance with the Immaculists, led by the Franciscans, believing that the Virgin was miraculously conceived without original sin, and the Sanctification party, led by

Figure 5.25 Max Hutzel, choir balcony, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. © J. Paul Getty Trust. GRI 86.P.8.

Figure 5.26 Max Hutzel, side chapel with Francisco Preciado de la Vega’s Immaculate Conception, Santissima Trinita degli Spagnoli, Rome. © J. Paul Getty Trust. GRI 86.P.8.

The Dominicans, holding that Mary was conceived in sin and later purified in the womb of her mother. Both the Crown and Church of Castile were ardent Immaculists, so when Alexander VII Chigi declared Mary immune from original sin in 1661, the news was met with great joy in Spain, and Seville in particular where the faithful were extraordinarily passionate. Yet the Immaculada theme was not only of unsurpassed importance to painters from Seville, such as Juan de Valdes Leal and Bartolome Esteban Murillo - both of whom would have been great inspirations to Preciado - it was also common in many Spanish churches and convents in Rome (Anselmi 2008: 239-300). It would have been inconceivable not to have one in a new Spanish church even if the theme had by now become somewhat tired.

In addition to his Immaculada altarpiece, Preciado painted an even more symbolic canvas for the church, the Vision at the Mass of St. John of Matha (1757), an allegory on the foundation of the Trinitarian Order (Cornudella i Carre 1997: 112). The painting was placed above an altar in the sacristy opposite the portrait bust of Fr. Diego Morcillo. The vault of the sacristy already contained a fresco by Gregorio Guglielmo depicting the two founding saints of the order, John of Matha and Felix of Valois. Seen together, the three works completed the allegory of the Trinitarian church and their new foundation in Rome.

Finally, Preciado produced a portrait of Simon de Rojas, a work that was first exhibited at Saint Peter’s Basilica on May 19, 1766, to celebrate the saint’s beatification (Fagiolo 1997: 178-9; Cornudella i Carre 1997: 113-14).21 THe church was decorated by the Roman architect Marco David and Preciado’s portrait was placed in the tribune, in front of Bernini’s Cathedra. The existence of this work remains in question as it may not have been the same painting he produced for the church of Santissima Trinita, a work which was signed and dated 1767 and produced for the Triduum feast for the Saint’s beatification on June 14-16 of the same year (Fagiolo 1997: 180). For this celebration, Preciado collaborated with D. Michele de Espinosa e la Torre to decorate the church’s fagade and interior. His painting of the Saint was placed in the entry chapel to the right dedicated to Simon de Rojas, where Antonio Gonzalez Velazquez’ Good Shepherd already hung. The painting remained there until the 1970s when it was re-located to the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (Villarroel 1998: 291).

For the remaining chapels, altarpieces were commissioned to various Roman and foreign artists, all of whom had studied under Sebastiano Conca or were connected with the Spanish community in Rome (Villarroel 1998: 284-6). These included the Martyrdom of St. Agnes (patron of the Trinitarian Order) by the Roman Marco Benefial (1684-1764), St. John of Matha by the Marchesan Gaetano Lapis (1706-76), a pupil of Conca, St. Catherine of Alexandria by the Sicilian Giuseppe Paladini (1721-94), and a portrait of St. Felix of Valois by the little known German painter and pupil of Benefial, Lambert Krahe (1712-90), who also produced a painting of St. Peter of Alcantara Giving Communion to St Teresa of Avila (c. 1751-56) for the church of San Pasquale Baylon. Krahe’s altarpiece for Santissima Trinita no longer exists, replaced by the Roman Andrea Casali’s portrait of St. Felix of Valois in 1775. A pupil of Conca, Andrea Casali (1705-84) also provided a painting of the Passion of Christ for the remaining altar and another eleven paintings in total that were located throughout the church and monastery.

On September 29, 1750, the ninth anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone, the church was consecrated (Villarroel 1998: 286). The Roman Diario Ordinario noted a few days later on October 3, 1750, that the church of Santissima Trinita had been completed, with the exception of the sacristy and a series of paintings for the remaining side chapels (Mancini 1997: II, 88-9). In 1752, Baldassare Mattei would complete the Spanish coat of arms for the fagade of the church. The Roman architect, Marco David (1739-65) finished the sacristy in 1758 by designing the wooden furniture to store the liturgical vestments and other sacred vessels. David also designed the wooden entrance (bussetto) to the church. In 1760, Gaspare Sibilla would complete the sculptural portrait of Morcillo for the sacristy. And as already mentioned, in the 1770s Andrea Casali would provide the Trinitarians with several canvases to complete the artistic build-out of the church. But perhaps most importantly, the Trinitarians’ expense book shows that in December 1750, Jose de Hermosilla was paid 250 scudi for his design of the church interiors (ATSR, Cuento del Gasto de la Fdbrica). At this point, Hermosilla achieved what no Spaniard before him had accomplished, the realization of a major monument in Rome and the recognition that comes with it.

The case of Santissima Trinita reveals a number of compelling design issues and cultural problems that extend well beyond the value of relating a particular moment in eighteenth-century Rome. Funding for the project came largely from South America, and it was associated with the exalting of the Trinitarian Order and the promotion of Spanish saints. The principal architects and artists involved in its completion came from the Iberian peninsula, and their contributions highlighted the importance that Roman planning strategies, building typologies and decorative vocabularies would continue to play in the early-modern world. More importantly though, the case of Santissima Trinita reveals how ardently the new Bourbon monarchs hoped to continue the tradition of Spanish donation in Rome, creating at the same time a distinct artistic culture that represented a truly global perspective of Ibero-American patronage.

World History

World History