"Alabama" is derived from Alibamu, "plantgather-ers," "medicine gatherers," or "thicket clearers." Alabamas were culturally related to the neighboring Creeks and Choctaws. Alabamas spoke a Musko-gean language.

The people worshipped the sun (fire), as well as a host of lesser deities and beings. Alabamas conducted the Green Corn ceremony as well as other ceremonies throughout the spring, summer, and fall. Most councils and ceremonies began with an emetic tea (black drink). Priests, doctors, and conjurers underwent a rigorous training period that included healing techniques, songs, and formulas.

Alabamas were part of the Creek Confederacy, although each village was politically sovereign. In most towns of the confederacy, a chief (miko) was chosen largely by merit. He was head of a democratic council that had ceremonial and diplomatic responsibilities.

Chunkey (a variety of hoop-and-pole in which an arrow was shot through a loop) was one of many popular games, most of which involved gambling. The dead were buried with their heads to the east and sometimes a knife in the hand for fighting eagles on the way to the afterworld. Alabamas had over fifty clans in the eighteenth century, although probably fewer before contact. Infidelity in marriage was an offense punishable by public whipping and exile.

Towns were laid out in a square and enclosed by walls up to several hundred feet long. By design, entry and egress were difficult: On one side the gate was too low for a horse to enter, and another side might open onto a steep embankment. Many towns were surrounded by mud-covered wooden stockades.

Dwellings were pole-frame structures with plastered walls and bark-covered or shingled, gabled roofs. The outer covering was of mud and grass or mats. Many families had a winter house and a summer house. These buildings, plus a granary and possibly a storehouse, were placed to form a square, in the manner of the ceremonial square ground.

Alabamas ate fish, squirrels and other small game, deer and other large game, and their crops. The winter hunt, during which men traveled up to 250 miles or more, lasted from after the harvest until the spring planting. Fish were taken with spears, bows and arrows, and poison. Women wove cane or palmetto baskets. Many points and knives were made of flint, although mortars and pestles were generally wooden. Bows were also made of wood (cedar was considered the best), with strings of hide (perhaps of bark in earlier times). Men also hunted with blowguns and possibly spears.

Alabamas exported flint and animal products and imported pipes and shells. Women made pottery and wove geometric designs into their baskets. Artisans worked silver ornaments from the sixteenth century on. Most pre-contact transportation was via dugout pirogues. Personal adornment included ornaments in pierced ears and noses, body paint, and various armbands, bracelets, and necklaces. In the late eighteenth century, women wore cloth skirts, as well as shawls, or capes. Men wore

Breechclouts, cloaks or shirts, and bear or buffalo robes in the winter. In battle, the war chief carried along the sacred war ark or medicine bundle. Life (of one's own people) was considered precious, and warriors were extremely careful not to risk inopportune or imprudent fighting or capture.

Alabamas probably descended from Mound Builder cultures and may have originated north and west of the Mississippi. They encountered a hostile Spanish party under Hernando de Soto in 1540. By the early eighteenth century they had become allies of the French, who built Fort Toulouse in Alabama country in 1713.

Many Alabamas left their homeland following the French defeat in 1763. Some joined the Semi-noles in Florida. Some resettled north of New Orleans, and later some of that group moved on to western Louisiana and Texas. Land given them in recognition of their contribution in the 1836 fight against Mexico was promptly stolen by nonNatives. In 1842, the Alabamas and the Coushatta Indians were given a 1,280-acre reservation along the Trinity River. The United States added 3,081 acres to that reservation in 1928. In 1954 the tribe voluntarily terminated its relationship with the federal government, at which time the state took over control of the reservation. The tribe reverted to federal status in 1986.

Those who remained in Alabama fought unsuccessfully with the Creeks against non-Natives in the 1813-1814 Creek War. Survivors of that conflict settled in the Alabama town of Tawasa. Most were resettled in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) with the Creeks in the 1830s. Part of the Creek Nation until 1938, the Alabama-Quassartes at that time received a federal charter, several hundred acres of land, and political, but not administrative, independence.

Louisiana Alabamas maintained a subsistence economy during the early twentieth century, gradually entering the labor market. Tourism and tourist-related sales of cane baskets and woodcrafted items began to grow in midcentury.

See also Creek War; Mound Cultures of North America; Muskogean Language; Seminole Wars.

See Tunica.

"Caddo" means "true chiefs," from Kadohadacho, "principal tribe." The Caddo Indians included people of the Natchitoches Confederacy (Louisiana), the Hasinai (Tejas or Texas) Confederacy (Texas), the Kadohadacho Confederacy (Texas and Arkansas), and the Adai and Eyish people. There were about twenty-five Caddo tribes in the eighteenth century. Caddos spoke a Caddoan language.

The people's supreme deity was known as Ayanat Caddi. There were also other deities and spirits, including the sun. Most annual ceremonies revolved around the agricultural cycle. Each Caddo tribe was headed by a powerful chief, who was assisted by other people of authority. Among the Hasinais (at least), a high priest had supreme authority. Clans were more hierarchical and social classes more pronounced among the western Caddos than in the east. Shell beads were used as a medium of exchange. Premarital sexual liaisons were condoned. In some tribes, men were allowed to have more than one wife, although in others a woman might not allow it. Divorce was easily obtained and occurred regularly.

At least one seventeenth-century town had over 100 houses. Some villages may have been reinforced with towered stockades. Houses in the east were round, about fifteen feet high and between twenty and sixty feet in diameter. They were constructed of a pole frame covered with grass thatch, through which smoke from the cooking fires exited; roofs came all the way to the ground. Western Caddos built earth lodges, with wooden frames and brush, grass, and mud walls reaching to the top. There were also outside arbors. Sacred fires always burned in circular temples.

Women grew two corn crops a year, as well as beans, pumpkins, sunflowers, and tobacco. They also gathered wild foods such as nuts, acorns, mulberries, strawberries, blackberries, plums, pomegranates, persimmons, and grapes. Agricultural products were most important in the diet, although buffalo grew in importance as the group moved westward. Men hunted deer, bear, raccoon, turkey, fowl, and snakes. They stalked deer using deer disguises. Dogs may have assisted them in the hunt. Fish were caught where possible.

Caddos exported Osage orange wood and salt, which they obtained from local mines (licks) and boiled in earthen (later iron) kettles. They imported Quapaw wooden platters, among other items. Their

Fine arts included basketry, pottery, and carved shells, and they used single-log dugout canoes and cane rafts to navigate bodies of water.

Most clothing was made of deerskin. Men wore breechclouts, untailored shirts, and cloaks. Women wore skirts and a poncho-style upper garment and painted their bodies. They parted their hair in front and fastened it behind. Both wore blankets or buffalo robes and tattooed their faces and bodies, especially in floral and animal patterns.

Caddoans are thought to have originated in the Southwest. They reached the Great Plains in the midtwelfth century and the fringes of the Southeast cultural area shortly thereafter. They gave the Spanish under Hernando de Soto a mixed reception in 1541. Few of the Spanish missions in their country had any success.

Trade with the French began in the early seventeenth century. The Indians traded their crops for animal pelts, which they then traded to the French for guns and other items of non-Native origin. During the eighteenth century, Caddo villages suffered from Spanish-French colonial battles. Many tribes were wiped out by disease during that period.

In 1835, the Caddos ceded their Louisiana land and moved to Texas. In the 1850s, however, nonNative Texans drove all Indians out of Texas, and the Caddos fled from their brutality to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma). In 1859, the United States confined them to a reservation along the Washita River, which the Wichitas and Delawares later joined.

Rather than support the Confederacy, most Caddos fled to Kansas during the Civil War, returning in 1868. Some scouted for the U. S. Army during the Plains wars, in part as a strategy of supporting farmers against nomads. The boundaries of their reservation were secured in 1872, but, despite Caddo objections, most of the reservation was allotted around 1900. After extensive litigation and appeals, the tribe won over $1.5 million in land claim settlements in the 1980s.

See also Agriculture; Confederacies; Fur Trade.

The Catawba people were also known as Issa or Esaw, "People of the River." Catawbas traditionally lived along the North Carolina-South Carolina border, especially along the Catawba River. Catawba is probably a Siouan language.

The people made use of wooden images in their ceremonies, which were relatively unconnected to the harvest. Enemies were killed to accompany the dead to an afterworld. There were two Catawba bands in the early eighteenth century. Some of their chiefs—men and women—were quite powerful.

Catawbas may have practiced frontal head deformation. The chunkey game was a variety of hoop-and-pole (in which an arrow was shot through a loop), played with a stone roller. They also played stickball (lacrosse). At puberty, young women learned the proper way to wear decorative feathers. Doctors and conjurers cured and detected thieves by consorting with spirits. Men alone were punished in cases of adultery. Divorce was easy to obtain, and widows could remarry at once.

Six early villages were located in river valleys. People lived in bark-covered pole-frame houses. The town houses were circular, as were the temples. Open arbors were used in the summer. Women grew corn, beans, squash, and gourds. Men hunted widely for large and small game, including buffalo, deer, and bear. The people also ate fish, pigeons, acorns, and various other wild plant foods. Blowguns with an average length of five to six feet and with an effective range of no more than thirty feet were used to bring down birds.

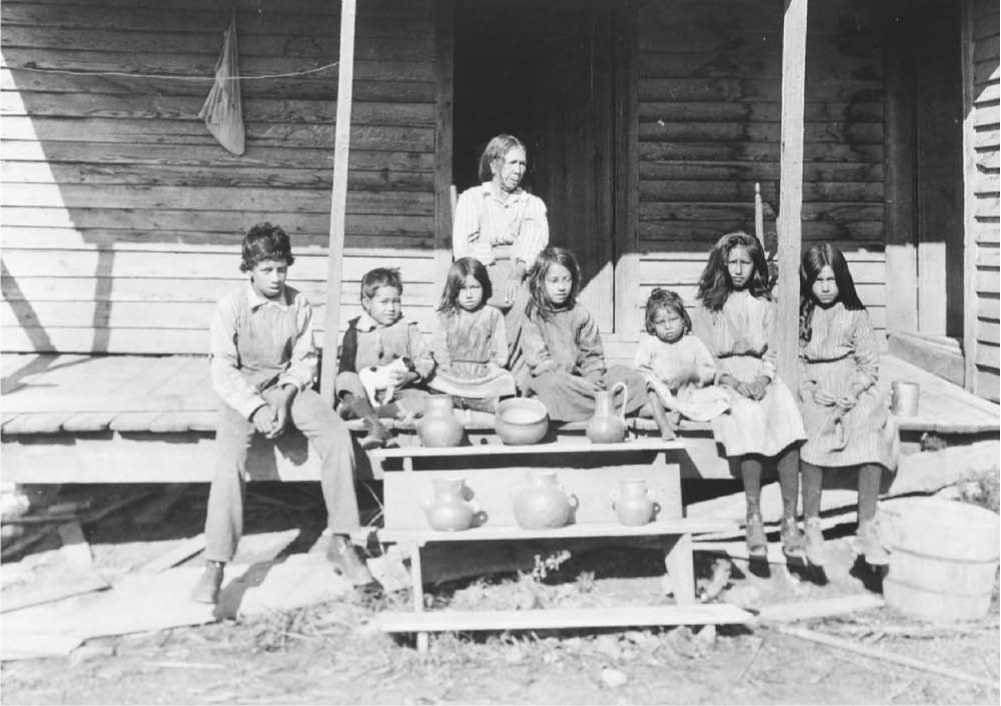

The main regional aboriginal trade routes ran right through Catawba territory. The Catawbas became heavily involved with British traders, especially in the mideighteenth century but beginning at least in 1673. Pottery was an ancient and highly developed Catawba art. It was often stamped with a carved piece of wood before firing. Rivers were navigated on dugout and possibly birchbark canoes. Chiefs wore headdresses of wild turkey feathers. Women may have worn leggings as well, when mourning, as special clothing made from tree moss.

Catawbas may have come to the Carolinas from the northwest. They first encountered non-Natives— Spanish explorers—in the midsixteenth century. Extensive contact with British traders in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries transformed their lives. A dependence on non-Native goods caused them to hunt ever farther afield for pelts with which to purchase such goods. Encroachment on other peoples' hunting grounds combined with the heavy volume of goods carried along the trade routes encouraged increased attacks by enemy Indians. Catawbas also underwent severe depopulation from disease.

Catawba potter Sarah Jane Ayers Harris and seven grandchildren, seated on her porch with her pottery, ca. 1910. (Library of Congress)

To maintain trade relations with the colonists, the Catawbas took their side in a 1711-1713 war with the Tuscarora Indians. By 1715, however, some Catawbas had taken the Indian side in the Yamasee War, rebelling against unfair trade practices, forced labor, and slave raids. The non-Native victory in this conflict broke the power of the local Indians.

In the mideighteenth century smallpox epidemics almost wiped the tribe out: Their pre-contact population of about 6,000 had declined by over 90 percent to 500 or fewer. Alcohol sold and aggressively promoted by Anglo traders took many more lives. Catawbas tended to absorb local tribes who suffered the same fate, such as the Cheraws, Suga-rees, Waxhaws, Congarees, Santees, Pedees, and Waterees.

In 1760-1761 the Catawbas were forced by their dependence on the state of South Carolina to fight against the powerful Cherokees in the French and Indian War. By 1763 they were confined to a fifteen-square-mile (144,000-acre) reservation, as nonNatives continued to take their former lands. Part of the agreement creating the reservation stipulated that non-Indians would be evicted from it (which never happened) and that the Catawbas continued to enjoy hunting rights outside the area. Their last great chief, Haigler, or Arataswa, died at that time.

The declining tribe took the patriot side in the American Revolution. In 1840, the few remaining Catawbas signed a treaty with the state of South Carolina, agreeing to cede lands in that state and move to North Carolina. Unable to buy land there, however, most dispersed among the Cherokees and Pamunkeys, although a very few remained in South Carolina. In the 1850s, however, most Catawbas who had gone to live with the Cherokees returned to South Carolina. A few families moved to Arkansas, the Indian Territory, Colorado, Utah, or elsewhere. Those in South Carolina acquired a reservation of 630 (of the original 144,000) poor-quality

Acres. They also obtained the promise of annual payments from the state.

Many South Carolina Catawbas began sharecropping at that time but returned occasionally to live on the reservation. They also continued to speak their language and to make their traditional crafts. The Catawba Indian School opened in 1896 and ran until 1962. Mormons also played a large role in educating Catawba children beginning in the 1880s.

Many Catawbas worked in textile mills beginning after World War I. The Indians added to their reservation by purchasing land in the midtwentieth century. By that time, however, traditional Catawba culture had all but expired. Although the federal trust relationship was formally begun only in 1943 as a result of Catawba legal pressure, in 1962 the tribe voluntarily ended its relationship with the federal government, at which time individuals took over possession of the recently purchased tribal lands.

See also Pottery; Mormon Church; Trade.

"Cherokee" is probably from the Creek tciloki, "people who speak differently." Their self-designation was Ani-yun-wiya, "Real People." With the Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, the Chero-kees were one of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes; this non-Native appellation arose because by the early nineteenth century these Indians dressed, farmed, and governed themselves nearly like white Americans. At the time of contact the Cherokees were the largest tribe in the southeast. Cherokees were formerly known as Kituhwas.

Cherokee is an Iroquoian language. The lower towns spoke the Elati dialect; the middle towns spoke the Kituhwa dialect; the upper (overhill and valley) towns spoke the Atali dialect. The dialects were mutually intelligible with difficulty.

The tribe's chief deity was the sun, which may have had a feminine identity. The people conceived of the cosmos as being divided into three parts: an upper world, this world, and a lower world. Each contained numerous spiritual beings that resided in specific places. The four cardinal directions were replete with social significance. Tribal mythology, symbols, and beliefs were complex, and there were also various associated taboos, customs, and social and personal rules.

Many ceremonies revolved around subsistence activities as well as healing. The primary one was the annual Green Corn ceremony (Busk), observed when the last corn crop ripened. Medicine people (men and women) could, by magical means, influence events and the lives and fortunes of people. Witches, when discovered, were summarily killed. Learning sorcery took a lifetime. Medicine powers could be used for good or evil, and the associated beads, crystals, and formulas were a regular part of many people's lives.

The various Cherokee villages formed a loose confederacy. There were two chiefs per village: a red, or war, chief, and a white chief (Most Beloved Man or Woman), who was associated with civil, economic, religious, and juridical functions. Chiefs could be male or female, and there was little or no hereditary component. There was also a village council, in which women sat, although usually only as observers. The Cherokees were not a cohesive political entity until the late eighteenth century at the earliest.

There were seven matrilineal clans in the early historic period. Cherokees regularly engaged in ceremonial purification, and they paid careful attention to their dreams. Both men and women, married and single, enjoyed a high degree of sexual freedom. Divorce was possible; men who were thrown out returned to their mothers. Children were treated gently, and they behaved with decorum. In general, Cherokees, valuing harmony as well as generosity, tried to avoid conflict.

Intraclan, but not interclan, murder was a capital offense. Names were changed or added to frequently. As with chiefs, towns may also have been considered red and white. Women owned the houses and their contents; this custom, along with matrilin-eal descent and the clan system, weakened with increasing exposure to non-Native society. People did not address each other directly. In place of public sanctions, Cherokees used ostracism and public scorn to enforce social norms.

Towns were located along rivers and streams. They contained a central ceremonial place and in the early historic period were often surrounded by palisades. People built rectangular summer houses of pole frames and wattle, walls of cane matting and clay plaster, and gabled bark or thatch roofs. The houses, about sixty or seventy feet by fifteen feet, were often divided into three parts: a kitchen, a dining area, and bedrooms. Some were two stories high, with the upper walls open for ventilation.

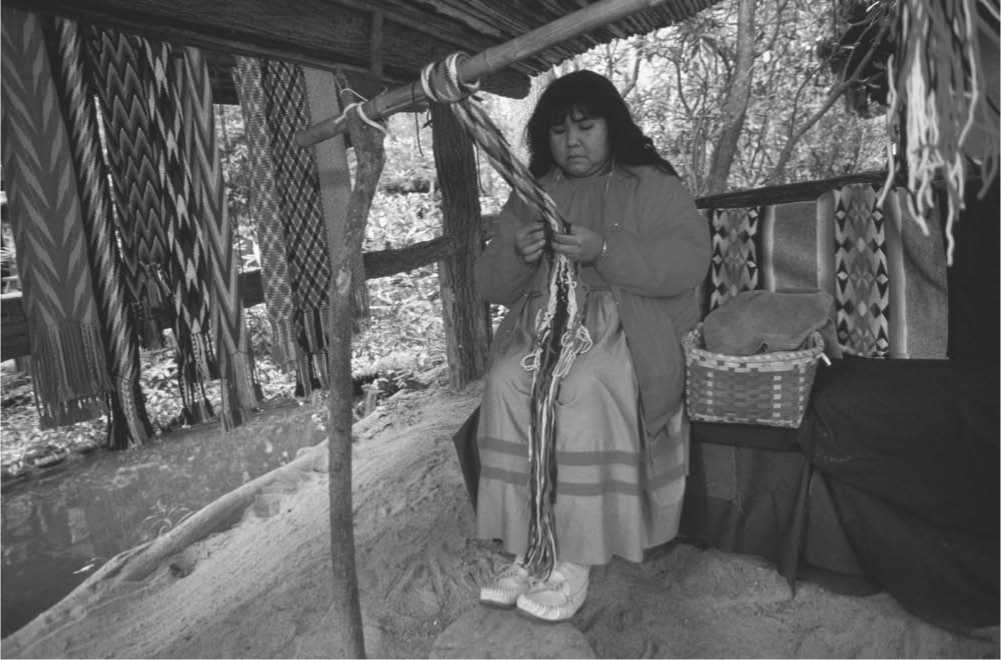

In a recreated Cherokee village, Cherokee tour guides show visitors the daily life and crafts of the Cherokees approximately 300 years ago. (Raymond Gehman/Corbis)

There was probably one door. Beds were made of rush mats over wood splints, and animal skins served as bedding.

Cherokees were primarily farmers. Women grew corn (three kinds), beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco, the latter used ceremonially. Wild foods included roots, crab apples, persimmons, plums, cherries, grapes, hickory nuts, walnuts, chestnuts, and berries. Men hunted various animals, including deer, bear, raccoon, rabbit, squirrel, turkey, and rattlesnake. They fished occasionally, and they collected maple sap in earthen pots and boiled it into syrup. Hunting gear included the bow and arrow, stone hatchet, and flint knife. Smaller animals and birds were shot with darts blown out of hollow nine - to ten-foot-long cane stems; these blowguns were accurate up to sixty feet.

Cherokee pipes were widely admired and easily exported. The people also traded maple sugar and syrup. They imported shell wampum that was used as money. Their plaited cane baskets, pottery, and masks carved of wood and gourds were especially fine.

Men built thirty - to forty-foot-long canoes of fire-hollowed pine or poplar logs. Each canoe could hold between fifteen and twenty people. Women made most clothing of buckskin and other skins and furs as well as of mulberry-bark fibers. Men wore breechclouts; women wore skirts. In the winter, both wore bear or buffalo robes. Men also wore shirts and leggings, and women wore capes. Both sexes wore moccasins as well as nose ornaments, bracelets, and body paint.

Each village had a red (war) chief as well as a War Woman, who accompanied war parties. She fed the men, gave advice, and determined the fate of prisoners. Women also distinguished themselves in combat and often tortured prisoners of war. The people often painted themselves, as well as their canoes and paddles, for war. The party carried an ark or medicine chest to war, and it left a war club engraved with its exploits in enemy territory.

The Cherokees probably originated in the upper Ohio Valley, the Great Lakes region, or someplace else in the north. They may also have been related to the Mound Builders. The town of Echota,

On the Little Tennessee River, may have been the ancient capital of the Cherokee Nation.

They encountered Hernando de Soto about 1540, probably not long after they arrived in their historic homeland. Spanish attacks against the Indians commenced shortly thereafter, although new diseases probably weakened the people even before Spanish soldiers began killing them. There were also contacts with the French and especially the British in the early seventeenth century. Traders brought guns around 1700, along with debilitating alcohol.

The Cherokees fought a series of wars with Tus-carora, Shawnee, Catawba, Creek, and Chickasaw Indians early in the eighteenth century. In 1760 the Cherokees, led by Chief Oconostota, fought the British as a protest against unfair trade practices and violence practiced against them as a group. Cherokees raided settlements and captured a British fort but were defeated after two years of fighting by the British scorched-earth policy. The peace treaty cost the Indians much of their eastern land, and, in fact, they never fully recovered their prominence after that time.

Significant depopulation resulted from several mideighteenth century epidemics. Cherokee support for Britain during the American Revolution encouraged attacks by North Carolina militia. Finally, some Cherokees who lived near Chattanooga relocated in 1794 to Arkansas and Texas and in 1831 to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). These people eventually became known as the western Cherokees.

After the American Revolution, Cherokees adopted British-style farming, cattle ranching, business, and government, becoming relatively cohesive and prosperous. They also owned slaves. They sided with the United States in the 1813 Creek War, during which a Cherokee saved Andrew Jackson's life. The tribe enjoyed a cultural renaissance between about 1800 and 1830, although they were under constant pressure for land cession and riven by internal political factionalism.

The Cherokee Nation was founded in 1827 with "Western" democratic institutions and a written constitution (which specifically disenfranchised African Americans and women). By then, Cherokees were intermarrying regularly with non-Natives and were receiving increased missionary activity, especially in education. Sequoyah (also known as George Gist) is credited with devising a Cherokee syllabary in 1821 and thus providing his people with a written language. During the late 1820s, the people began publishing a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix.

The discovery of gold in their territory led in part to the 1830 Indian Removal Act, requiring the Cherokees (among other tribes) to relocate west of the Mississippi River. When a small minority of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, ceding the tribe's last remaining eastern lands, local nonNatives immediately began appropriating the Indians' land and plundering their homes and possessions. Indians were forced into internment camps, where many died, although over 1,000 escaped to the mountains of North Carolina, where they became the progenitors of what came to be called the eastern band of Cherokees.

The removal, known as the Trail of Tears, began in 1838. The Indians were forced to walk 1,000 miles through severe weather without adequate food and clothing. About 4,000 Cherokees, almost a quarter of the total, died during the removal, and more died once the people reached the Indian Territory, where they joined—and largely absorbed—the group already there. Following their arrival in Indian Territory, the Cherokees quickly adopted another constitution and reestablished their institutions and facilities, including newspapers and schools. Under Chief John Ross, most Cherokees supported slavery and also supported the Confederate cause in the Civil War.

The huge "permanent" Indian Territory was often reduced in size. When the northern region was removed to create the states of Kansas and Nebraska, Indians living there were again forcibly resettled. One result of the Dawes Act (late 1880s) was the "sale" (the virtual appropriation) of roughly 2 million acres of Indian land in Oklahoma. Oklahoma became a territory in 1890 and a state in 1907. Although the Cherokees and other tribes resisted allotment, Congress forced them to acquiesce in 1898. Their land was individually allotted in 1902, at about the same time their Native governments were officially "terminated."

Ten years after the Cherokee removal, the U. S. Congress ceased efforts to round up the eastern Cherokees. The Indians received North Carolina state citizenship in 1866 and incorporated as the eastern band of Cherokee Indians in 1889. In the early twentieth century, many eastern Cherokees were engaged in subsistence farming and in the local timber industry. Having resisted allotment, the tribe took steps to ensure that it would always own

Its land. Although the Cherokees suffered greatly during the Depression, the Great Smoky Mountain National Park (1930s) served as the center of a growing tourist industry.

In the 1930s, the United Keetoowah Band (UKB), a group of full-bloods opposed to assimilation, formally separated from the Oklahoma Cherokees. (The name "Keetoowah" derives from an ancient town in western North Carolina.) The group originated in the antiallotment battles at the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century the UKB reconstructed several traditional political structures, such as the seven clans and white towns, as well as some ancient cultural practices that did not survive the move west. They received federal recognition in 1946.

See also Cherokee Nation v. Georgia; Cherokee Phoenix and Indian Advocate; Creek War; Indian Removal Act; Mankiller, Wilma; Ross, John; Sequoyah; Trail of Tears.

"Chickasaw" is a Muskogean name referring to the act of sitting down. The Chickasaws were culturally similar to the Choctaws. Along with the Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, the Chickasaws were one of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes. Chickasaw is a Muskogean language.

The supreme deity was Ababinili, an aggregation of four celestial beings: Sun, Clouds, Clear Sky, and He That Lives in the Clear Sky. Fire, especially the sacred fire, was a manifestation of the supreme being. Two head priests (hopaye) presided over ceremonies and interpreted spiritual matters. Healers (aliktce), who combated evil spirits by using various natural substances, and witches were two types of spiritual people.

Political leadership was chosen in part according to hereditary claim but also according to merit. The head chief, chosen from the Minko clan, was known as the High Minko. Each clan also had a chief. There was also a council of advisers, which included clan leaders and tribal elders. The fundamental units were local groups.

Key Chickasaw values included hospitality and generosity, especially to those in need. Two divisions were in turn divided into many ranked matri-lineal clans. The people played lacrosse, chunkey (in which an arrow was shot through a hoop), and other games, most of which included gambling and had important ritual components. Tobacco was used ritually and medicinally. Murder was subject to retaliation.

Boys were toughened by winter plunges into water and special herbs. Women were secluded in special huts during their menstrual periods. Marriage involved various gift exchanges, mainly food or clothing. A man might have more than one wife. Men avoided their mothers-in-law out of respect. In cases of adultery only the woman was punished, often by a beating or by an ear or nose cropping. Chickasaws practiced frontal head deformation.

The dead were buried in graves under houses, along with their possessions, after an elaborate funeral rite. They were placed in a sitting position facing west, with their faces painted red. After death they were only vaguely alluded to and never directly by name. All social activities ceased for three days following a death in the village. Chicka-saws maintained the concept of a heaven generally in the west, the direction of witchcraft and uneasy spirits.

Chickasaws built their villages on high ground near stands of hardwood trees. They were often palisaded and more compact during periods of warfare. Rectangular summer houses were of pole-frame construction, notched and lashed, with clapboard sides and gabled roofs covered with cypress or pine-bark shingles.

Winter houses were semiexcavated and circular, about twenty-five feet in diameter, with a narrow, four-foot-high door. They were plastered with at least six inches of clay and dried grass. Bark shingles or thatch covered conical roofs with no smoke holes. Furniture included couches and raised wood-frame beds, under which food was stored. Town houses or temples were of similar construction.

Crops—corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers— were the staple foods. Men also hunted buffalo, deer, bear, and numerous kinds of small game, including rabbits but probably not beaver or opossum. Birds and their eggs were included in the diet. Women gathered nuts, acorns, honey, onions, persimmons, strawberries, grapes, and plums. Tea was made from sassafras root. Chickasaws ate a variety of fish, including the huge Mississippi catfish (up to 200 pounds).

Earthen pots of various sizes and shapes served a number of purposes. Men stunned fish with buckeye or green walnut poison. Women wove mulberry bark in a frame and used the resulting textile in

Floor and table coverings. Most clothing was made of deerskin, although other hides, including beaver, were also used. Men wore breechclouts, with deerskin shirts and bearskin robes in cold weather. Most kept their hair in a roach soaked in bear grease. There were also high boots for hunting. Women wore long dresses and added buffalo robes or capes in the winter. People generally went barefoot, although they did make moccasins of bear hide and occasionally elk skin.

Chickasaws traded as far away as Texas and perhaps even Mexico. Among other items, they traded deerskins for conch shell to use as wampum. Cloth items (from woven mulberry inner bark) were decorated with colorful animal and human figures and other designs. The people also made exceptional dyed and decorated cane baskets. Men hollowed dugout canoes out of hardwood trees.

Chickasaws were known as fierce, enthusiastic, and successful warriors. Raiding parties usually consisted of between twenty and forty men, their faces painted for war. They engaged in ritual preparation before they departed, and, upon their return, ritual celebration, which might include the bestowal of new war names.

The Chickasaws may once have been united with the Choctaws. The people encountered Hernando de Soto in 1541. At first welcoming, as their customs dictated, they ultimately attacked the Spanish when the latter tortured some of them and tried to enslave others.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, warfare increased with neighboring tribes as the Chickasaws expanded their already large hunting grounds to obtain more pelts and skins for the British trade. Increasingly dependent on this trade, they did not shrink from capturing other Indians, such as the Choctaws, and selling them to the British as slaves. In general, the Chickasaws' alliance with the British during the colonial period acted as a hindrance to French trade on the Mississippi.

Constant warfare with the French and their Choctaw allies during the eighteenth century sapped the people's vitality. In part to compensate, they began absorbing other peoples, such as several hundred Natchez as well as British traders. A pattern began to emerge in which descendents of British men and Chickasaw women (such as the Colbert family) became powerful tribal leaders. Missionaries began making significant numbers of converts during that time.

Tribal allegiance was divided during the American Revolution, with some members supporting one side, some the other, and some neither. The overall goal was to preserve traditional lands. With game growing scarce, many Chickasaws became exclusively farmers during the early to midnineteenth century. Some also began cotton plantations, and the tribe owned up to 1,000 African-American slaves during that period. By 1830 they had a written code of laws (which banned whiskey) and a police force.

As non-Native settlement of their lands increased during the 1820s, many Chickasaws migrated west, ceding land in several treaties (1805, 1816, 1818) during the period. Finally they ceded all lands east of the Mississippi in 1832. Roughly 3,000 Chickasaws were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) after 1837, where many died of disease, hunger, and attacks by Plains Indians who resented the intrusion. The Chickasaws fared somewhat better than the Cherokees, being able to purchase many supply items, including riverboat transportation, with tribal funds. Most settled in the western part of Choctaw lands.

Survivors of the ordeal resumed farming and soon, with the help of their slaves, grew a surplus of crops. However, as a tribe the people had lost most of their aboriginal culture. Their own reservation and government were formally established in 1855 and lasted until Oklahoma statehood in 1907. In the years before the Civil War, the people operated schools, mills, and blacksmith shops, and they had started a newspaper. Chickasaws fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Unlike some other Oklahoma tribes of southeast origin, the Chicka-saws never adopted their freed slaves.

Their lands were allotted around 1900. All tribal governments in Oklahoma were dissolved by Congress in 1906. By 1920, of the roughly 4.7 million acres of preallotment Chickasaw land, only about 300 remained in tribal control, a situation that severely hampered tribal political and economic development well into the century. Many prominent twentieth-century Oklahoma politicians were mixed-blood Chickasaws. From the 1940s on, individuals received payments from the sale of land containing coal and asphalt deposits.

See also Agriculture; Indian Removal Act; Muskogean Language; Slavery; Trade.

"Chitimacha" may have meant "those living on Grand River," "those who have pots," or "men altogether red." They may have comprised three or four separate tribes in the early sixteenth century. The Chitimachas traditionally lived along the lower Louisiana coast, especially around Grand Lake, Grand River, and Bayou Teche. Chitimacha may be a language isolate, or it may be related to Tunican.

Chitimachas recognized a sky god, possibly feminine in nature. Boys and girls sought and obtained guardian spirits through solitary quests. Priests oversaw religious life. A twelve-foot-square temple on Grand Lake served as a center of religious activity, especially for the annual six-day midsummer festival. The main event here was the male adult initiation ceremony, during which the young men fasted and danced until exhausted.

There was a chief in each town and a subchief in each village; leadership was largely hereditary. Head chiefs possessed a large measure of authority and power and were fed, at least in part, by others. Among the different social classes, priests, headmen, and curers constituted a nobility. There may also have been clans. Women might obtain any religious or political position. The dead may have been laid on scaffolds, where special people (Buzzard Men) disposed of flesh and returned cleaned bones to the families, where they were eventually buried under mounds of earth.

Village populations reached up to 500 in the early historic period. Pole-frame houses were covered with palmetto thatch. The people ate bear, alligators, turtles (and their eggs), and deer, among other animals. They were highly dependent on fish and shellfish. Women grew sweet potatoes as well as beans, squash, sunflowers, and possibly four varieties of corn. They also gathered water lily seeds, palmetto seeds, nuts, and various wild fruits and berries.

Exports included fish and salt; imports, mainly from inland tribes, included flint, stone beads, and arrow points. They traded often with the Atakapa and the Avoyel Indians. Patterned black-and-yellow cane baskets, made with a unique double weaving technique, were especially fine arts. Extensive canoe transportation was made easier by the natural harbor provided by Grand Lake. Nose ornaments, bracelets, and earrings were common personal adornments. Both sexes kept their fingernails long.

Men wore their hair in roaches, or perhaps long, and decorated with feathers and lead weights.

Resident in their historic area for at least 2,500 years, the Chitimachas may have migrated south from the region of Natchez at some early time and east from Texas still earlier. Their decline began with the French arrival in the late seventeenth century. French slaving among the Indians created a generally hostile climate between the two peoples, especially in the early eighteenth century. Peace was established in 1718, but by then the Chiti-macha population had suffered great losses through warfare and disease. Survivors were forcibly relocated north or taken away as slaves.

The influx of French Acadians in the late eighteenth century led to intermarriage (with Acadians as well as with other surviving local Indian groups), further land thefts, and the increased influence of Catholicism. In 1917, the Indians' remaining land base was privately purchased and sold to the United States. Throughout the twentieth century, chiefs have continued to govern the people and struggle to retain tribal land and sovereignty.

See also Basketry; New France and Natives; Slavery.

"Choctaw" was originally Chahta. An early name for the tribe might have been Pafallaya, or "long hair." They were culturally related to the Chickasaws and Creeks. With the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, they were regarded by whites as one of the Five Civilized Tribes. Choctaw is a Muskogean language.

Choctaws worshipped the sun and fire as well as a host of lesser deities and beings. They celebrated the Green Corn ceremony and other festivals, mainly in the late summer and fall. The tribe was organized into two divisions. Three or four districts were each headed by a chief and a council. Also, each town had a lesser chief and a war chief. The power of these chiefs was relatively limited, and the Choctaws were among the most democratic of all southeastern Indians. Although there was no overall head chief, a national council did meet on occasion.

The people placed a high priority on peace and harmony. Lacrosse, played with deerskin balls and raccoon-skin-thong stick nets, was a huge spectator

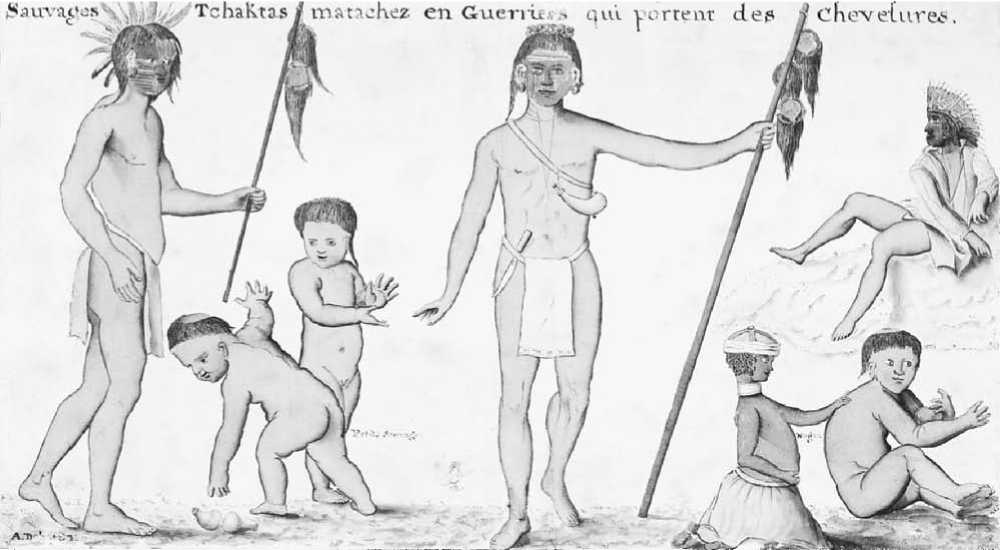

An eighteenth-century sketch of Choctaw warriors and children. One of the Five Civilized Tribes of the Old South, the Choctaws were an ethnically mixed people who occupied three river valleys in modern Mississippi. Although the Choctaws' assistance was vital to the victories of Major General Andrew Jackson's army in the south, their land was stolen and they were removed to the Indian Territory in the 1830s. (Corbis)

Sport as well as a means for settling disputes. Rituals and ceremonies began days before a game. There was always gambling; sometimes the stakes included a person's net worth.

Women adulterers were severely punished; some contributed to a class of prostitutes. Both men and women observed food taboos when a child was born. Infants' heads were generally shaped at birth. Maternal uncles taught and disciplined boys. At puberty, boys were tattooed, and some wore bear claws through their noses. Homosexuality was accepted.

Perhaps 100 or more Choctaw villages (summer and winter) existed in the seventeenth century. Border towns, especially in the northeast, were generally fortified, whereas interior towns were more spread out. Towns, which were groups of villages and houses surrounded by farms, usually contained a public game/ceremonial area.

Men built pole-frame houses roofed with grass or cane reed thatch and walled with a number of materials, including crushed shell, hide, bark (often pine or cypress), and matting. Summer houses were oblong or oval with two smoke holes. The winter houses were circular and insulated with clay.

Choctaws farmed bottomland fields along the lower Mississippi. They often realized food surpluses. Women, with the assistance of men, grew corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, tobacco, and later potatoes and melon. Also, in the eighteenth century they grew leeks, garlic, cabbage, and other garden produce, the latter strictly for trade. Corn was also made into bread, as was sweet potato seed.

Large game, such as buffalo, deer, and bear (killed mainly for their fat), were particularly important when the harvest was poor. Small game included squirrel, turkey, beaver, otter, raccoon, opossum, and rabbit. Other foods included birds' eggs, fish, and wild fruits, nuts, seeds, and roots.

Fields were cleared using slash-and-burn technology. People fished using spears, nets, stunning poison, and buffalo hide traps. They carved bows, mortars, and stools of wood; made skin-covered gourd and horn pouches; and wove bags from twisted tree bark. Women wove and dyed baskets. Spun buffalo wool was also used as a fabric. Cane, another important raw material, was used for such items as knives, blowguns, darts, and baskets. Musical instruments included drums of skins stretched over hollowed logs, rattles, and rasps. Traders devel-

Oped a regional trade language mixed with sign language for wide communication.

Choctaws followed the general Southeastern dress of deerskin breechclouts, skirts, and tunics and buffalo or bear robes and turkey feather blankets for warmth. Some women made their skirts of spun buffalo wool plus a plant fiber. Both men and women wore long hair except for men in time of mourning. Both also tattooed their bodies. The Choctaws partook less of war than did many of their neighbors, although they did not shirk from defensive fighting. Adult captives were regularly burned; others were enslaved.

Choctaws probably descended from the Missis-sippian Temple Mound Builders and may once have been united with the Chickasaws. Early encounters with the Spanish, starting with Hernando de Soto about 1540, were not peaceful, as de Soto generally burned Choctaw villages as he passed through the region.

The French established a presence in Choctaw territory in the late seventeenth century, and the two groups soon became important allies, although there was always a faction of Choctaws friendly to the British. Fighting along with the French and other Indian tribes, the Choctaws helped defeat the Natchez revolt of 1729. Bitter internal fighting around 1750 between French and British supporters was resolved generally in favor of the former.

Intertribal war continued with the Chickasaws and the Creeks until the French cession in 1763 (at the conclusion of the French and Indian War). Choctaws fought the Creeks even after that, until the United States took "possession" of greater "Louisiana" in the early nineteenth century. Small bands of Choctaws began settling in Louisiana in the late eighteenth century. At the same time, alcohol, supplied mainly by British traders, was taking a great toll on the people.

Largely under the influence of their leader, Pushmataha, the Choctaws refused to join the panIndian Tecumseh confederacy. However, nonNatives continued pushing into the Choctaws' territory. One strategy that non-Natives used to gain Indian land was to encourage trade debt by offering unlimited credit. Under relentless pressure and threats, the Choctaws began ceding land in 1801. Although treaties usually called for an exchange of land, in practice the Indians seldom received the western land they were promised, in part because the United States traded land that was not the government's to give or that it had no intention of allowing the Indians to have.

By the 1820s, the Choctaws had adopted so many lifeways of the whites that the latter regarded them as a "civilized tribe." Nevertheless, and although the Choctaws had never fought the United States, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, requiring the Choctaws and other Southeast tribes to leave their homelands and relocate west of the Mississippi. A small minority of unrepresentative Choctaws signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, ceding all of their land in Mississippi, over 10 million acres. Articles in the treaty providing for Choctaws to remain in Mississippi were so full of loopholes that most of those who did so were ultimately dispossessed. At the same time, the state of Mississippi formally made the Indians subject to state laws, thus criminalizing tribal governments.

Removal of roughly 12,000 Choctaws took place between 1831 and 1834. Terrible conditions on this forced march of several hundred miles caused about a quarter of the Choctaws to die of fatigue, heartbreak, exposure, disease, and starvation. Many more died once they reached the Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Roughly 3,000 to 5,000 Choctaws escaped to the back country rather than join the removal. Many of these people were removed in the 1840s, but some remained. Although they continued living as squatters in a semitraditional manner, their condition declined. Officially illegal, they were plied with alcohol and relentlessly cheated, and they became disheartened.

The bulk of the people reestablished themselves out west and prospered in the years before the Civil War, with successful farms, missionary schools, and a constitutional government. Most Choctaws fought for the Confederacy; the war was a disaster for them and the other tribes. A relatively high percentage of Indians died in the war, and further relocations and dispossessions followed the fighting. After the war, the Choctaws paid for the removal of African Americans living on their territory, although most were eventually adopted into the tribe.

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the General Allotment Act and the Curtis Act were passed over the opposition of the tribes. These laws deprived Oklahoma Indians, including the Choctaws, of most of their land. The "permanent" Indian Territory became the state of Oklahoma in 1907 (the name "Oklahoma," a Muskogean word for "Red People," was introduced by a Choctaw

Indian), at which time the independent Choctaw nation became subject to U. S. control. The tribe spent decades attempting to reassert control over its institutions.

After the Reconstruction period, the Mississippi and Louisiana Choctaws lived by sharecropping, subsistence hunting, some wage labor, and selling or bartering herbs and handicrafts. Their community and traditions were kept alive in part by the retention of their language and their rural isolation, both from Euro-Americans, who branded them nonwhite, and African Americans, with whom the Choctaw refused to identify.

The government finally recognized the Mississippi Choctaws in the early twentieth century, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs began providing services, such as schools and a hospital, during the 1920s and 1930s. It began purchasing land for them as well. Reservations were created in 1944, and the tribe adopted a constitution and bylaws in 1945. Educational and employment opportunities remained severely limited until the 1960s owing to Mississippi's Jim Crow policies.

See also Agriculture; Forced Marches; Indian Removal Act; Mississippian Culture; Muskogean Language.

See Alabama.

"Creek," taken from Ochesee Creek, is the British name for the Ocmulgee River. The so-called Creeks were actually composed of many tribes, each with a different name, the most powerful of which was called the Muskogee (or Mvskoke), itself a collection of tribes who probably migrated from the Northwest. With the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, the Creeks became known by nonNatives in the early nineteenth century as the Five Civilized Tribes.

The Creek confederacy was a loose organization that united many Creek and non-Creek villages. Muskogee-speaking towns and tribes formed the core of the confederacy, although other groups joined as well. It was founded some time before 1540 but strengthened significantly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Traditionally, Upper Creeks lived along the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers, in Alabama. Creeks spoke two principal Muskogean languages.

The Green Corn ceremony, also called the Busk, marked the new year. It was both a thanksgiving ceremony and one of renewal. Some participants drank a black drink that was mainly caffeine and that induced vomiting when consumed in quantity; it was designed to purify the body. The ceremony also included dancing, fasting, feasting, games, and contests. It ended with a communal bath and an address from the head chief. Other ceremonies in the spring and early summer included "stomp dances." Another group of feasts culminated in the late fall Dance of the Ancient People.

The supreme being, "master of breath," presided over the Land of the Blessed Dead. It received an offering of the first buck killed each season and also a morsel of flesh at each meal. Its representative on earth was the Busk fire. There were also many spiritual beings, particularly dwarfs, fairies, and giants.

Tribal towns (talwas) were the main political unit. Each contained about 100 to over 1,000 people, and each was politically sovereign, the alliance among them determining the nature of the confederacy. Towns chiefs (mikos) were largely chosen by merit. The power of the chiefs was to influence (and to carry out certain duties), not to command. They were head of the democratic council, which had ceremonial and diplomatic responsibilities. Decisions were made by consensus. There was also a subchief and a war chief. A town crier announced governmental decisions to the people.

The council met daily in the square ground or the town house. The people drank "black drink" and smoked tobacco before each important council meeting. Part of the council was a group of elders known as the Beloved Men. There were also Beloved Women, although women generally did not have formal power. Another council, composed of white clan members, oversaw internal public works affairs.

A dual division within most tribes manifested itself in the existence of red towns and white towns. Red was associated with war, white with peace. There were also about forty matrilineal clans, unequal in prestige, with animal names. Clans were the fundamental social unit.

Lacrosse games were played between towns of different divisions, in part to relieve tensions. Games also had significant political and ritualistic signifi-

Cance. Unmarried women had considerable sexual freedom. Men could marry more than one wife. Marriage was formalized by gift giving, repeatedly in the case of multiple wives. Divorce was unusual, especially if there were children. Both parties were killed or punished in cases of adultery, unless they could escape punishment until the next Busk. Rape, incest, and witchcraft were capital offenses, as was nonseclusion during a woman's periods. Infanticide was permitted within the first month of life.

Women made pottery, baskets, mats, and other such items; prepared food and skins; made clothing; helped with the communal fields; and grew all the garden crops. Men also helped with the communal fields, and they hunted, fished, fought, played ball games, led ceremonies, built houses and other structures, and made tools. Men also carried skin pouches containing medicines, tobacco, and knives that hung by their sides.

Fifty towns, each with between thirty and 100 houses and located on river or creek banks, formed the original core of the confederacy. Each town was organized around a central square or plaza, which contained several features: a circular town (or hot) house; a game field; and a summer ceremonial house, or square ground. The square ground was actually four sheds around a square of one-half acre or so, in the center of which was the sacred fire. Private homes were clustered in groups of up to four. Each reasonably prosperous family had a winter house and a summer house, both generally rectangular.

A third structure was a two-story granary, one end of which was used for storing grain and roots (lower) and for meetings (upper). The other end, with open sides, was a general storage area (lower) and a reception area (upper). A fourth building, if one could afford it, was a storehouse for skins. The four buildings were placed to form a square, after the ceremonial square ground design.

Crops—corn, beans, and squash—were the staples. Hunting was important for meat and skins. Most men left the villages during the winter to hunt. Women often accompanied the hunting parties, mostly to attend to the meat and skins along the way. The people also ate fish.

Creeks utilized the Choctaw trade language. Some groups exported flint and salt. A pictographic system represented historical events. Women made pottery, glazed with smoky pitch, and cane and hickory splint baskets. Men made large cypress dugout canoes. Except on the Georgia coast, where they used tree moss, women made their clothes largely from skins and textiles. Skirts that reached below the knee were tied around the waist. Men wore breech-clouts and often leggings. Some young men wore nose ornaments and enlarged their ears with copper wire. Both sexes wore buffalo hide and deerskin moccasins as well as extensive tattoos. Boys often went naked until puberty. Rank was reflected in clothing and adornment.

There were three levels of warriors: war chiefs, big warriors, and little warriors, depending on their level of accomplishment. Most fighting took place in spring. The purpose was generally honor and revenge. Men painted their bodies black and red for war. A successful war party left signs to indicate who had done the deeds. Parties that resulted in the loss of many men, no matter how successful otherwise (captured horses, war honors, and so on) were considered failures. Enemies were often scalped and dismembered; those remaining alive might be enslaved or whipped and otherwise tortured by the women, unless they could escape.

The Creek people probably descended from Mississippian Temple Mound Builders, entering their historic area from the west. Hernando de Soto passed through the region in 1540. In the colonial wars, Creeks were traditional allies of the British, although they were often successful in playing the European nations against one another. Early on, the Creeks were grouped very informally into a lower section, located in eastern Georgia and more accommodating to Anglo society, and an upper section, more traditional and resistant to assimilation.

As British allies in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Creeks fought the Spanish as well as other Indian tribes, such as the Apalachees, the Timucuas, the Choctaws, and the Cherokees. They also absorbed some of the tribes they defeated in battle, such as part of the Apalachicolas and the Apalachees about 1704. Creeks took part in the 1715 Yamasee War, because years of British abuse, including slaving, rape, and cheating, had temporarily disrupted the Creek-British alliance. Following the Yamasee defeat, the bulk of the Creeks moved inland to the Chattahoochee River.

The Creeks were more cautious about choosing sides in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Few favored the colonists, however, which was reason enough for the victors to demand land cessions after the fighting. In the late eighteenth century, the Creek leader Alexander McGillivray

Dominated the confederacy's diplomatic maneuvering and attempted to reorganize its political structure to his advantage. In 1790 he signed a treaty, later repudiated by the leaders of the confederacy, accepting U. S. protection and involvement in the people's internal affairs.

World History

World History