By the early 20th century, a growing number of Americans had become concerned about the rapid consumption, and possible depletion, of the nation’s natural resources, and the Progressive Era included efforts to address such problems. After ebbing in the 1920s, government involvement in environmental issues increased during the 1930s as part of the agendas of presidents Herbert C. Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Hoover had sought with some success to promote conservation and resource management in the 1920s during his tenure as secretary of commerce in the cabinets of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. He had advocated legislation that regulated aspects of the fishing industry, for example, and approved construction of Boulder Dam. As president, Hoover continued to work for environmental protection by such efforts as supporting the development of flood control measures and encouraging oil conservation.

Like Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt had a long-standing interest in environmental issues. As governor of New York, he campaigned for responsible forestry and sponsored a number of reforestation initiatives. Forest preservation remained an integral part of Roosevelt’s conservation program during his presidency. More forestland—more than 11 million acres—was added to the government’s holdings by FDR’s administration than had been added under any previous administration. Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior, Harold Ickes, worked to establish a number of new national parks, including Shenandoah National Park in Virginia and Olympic National Park in Washington State. Roosevelt and Ickes also supported various state reforestation plans.

Although forest management continued to be important to conservationists, natural disaster helped bring another environmental issue to the forefront during the 1930s. In the southwestern plains, prolonged drought coupled with soil-depleting farming techniques left the land barren and exposed. The resultant environmental damage in the DUST bowl heightened awareness of soil erosion and the need for soil conservation. In 1933, FDR established the Soil Erosion Service as an emergency measure. Soil conservation efforts were expanded when the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), a permanent agency housed under the Department of Agriculture, was created in 1935. These agencies oversaw a number of conservation initiatives, including scientific research, flood control, reforestation, grazing and pasture regulations, and farmer education and cooperation programs.

Some environmental projects undertaken by the government during this period were designed to control the environment rather than protect it, and to allow expansion into previously inhospitable areas. The Reclamation Service became the Bureau of Reclamation in 1933 and experienced enormous growth in the 1930s. Through the building of massive dams, the bureau provided vast areas of the American West with water for irrigation and

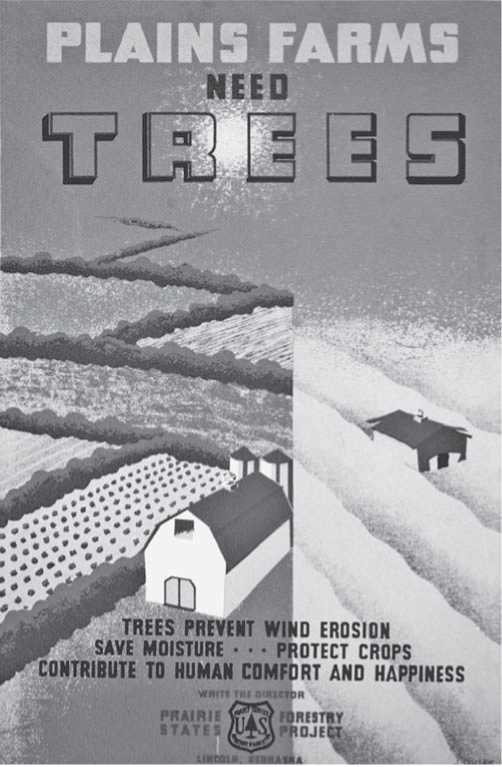

Poster, by Joseph Dusek (1940), advocating planting trees as a method of soil conservation (Library of Congress) hydroelectric power for industrial development. The dams were also designed to control flooding and soil erosion. Even more ambitious were the goals of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), an agency formed to spearhead the revitalization of the Tennessee Valley, one of the country’s most depressed areas. TVA planners hoped to combine reclamation and conservation projects with education and social programs in order to stimulate economic growth.

To accomplish his environmental goals, Roosevelt also incorporated conservation work into initiatives designed primarily to alleviate the nation’s economic woes. One of the most popular New Deal programs, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), established in 1933, furnished much of the labor for FDR’s forest and soil conservation programs. CCC enrollees planted over a billion trees, fought forest fires, and built roads, campgrounds, and recreation facilities in the national parks. They worked on flood control projects for the Army Corps of Engineers and carried out agricultural demonstrations for the SCS. They also worked on a number of reclamation projects carried out by the Bureau of Reclamation and assisted in improving wildlife habitats and grazing lands. Another program, the Public Works Administration, also provided laborers for a number of conservation projects.

The environmentalism of Hoover and Roosevelt, like that of their predecessors, was based largely on a belief in the importance of wise usage of the nation’s resources and a persuasion that the fundamental purpose of conservation was to ensure the availability of natural resources for future use and development. But government efforts in the 1930s also led to increased national consciousness about environmental issues. Private organizations such as the Sierra Club, Friends of the Land, and the National Wildlife Federation grew in size and number, helping build the foundation for a more preservationist environmentalism in the decades to follow.

Ironically, some of the very projects hailed as breakthroughs in environmental management in the 1930s and 1940s subsequently provoked criticism from environmentalists for being sources of ecological damage. Dam building, for instance, has frequently been blamed for a myriad of environmental problems in the American Southwest, including loss of wildlife habitat and increased salinity of the water supply. Similarly, some characterize the soil conservation programs of the era as misguided and overly expensive efforts to sustain commercial agriculture in areas essentially unfit for farming. And some developments of the war years, such as the increasing use of chemical pesticides, the harnessing of atomic power, and the expansion of suburbs, also presented significant environmental problems that would become issues in the postwar era.

Further reading: A. L. Riesch Owen, Conservation under FDR (New York: Praeger, 1983); John Salmand, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1935-1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press, 1967); Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

—Pamela J. Lauer

World History

World History