Prior to the American Revolution, most European-American women identified themselves primarily as members of households and families, deriving their status less from their own abilities and ambitions than from the statuses of their fathers and husbands. Women’s work focused largely on the household, including cleaning, child rearing, making clothing, processing and preserving food, and managing the dairy and the kitchen garden. The small number of women who managed businesses, farms, or plantations typically did so following a husband’s death (and even then this practice was exceptional). In New England, married women could serve as “deputy husbands,” an informal status allowing them to make legally recognized business decisions when their husbands were absent or ill. But a woman assumed the role of deputy husband as a temporary addition to their primary responsibilities, which remained centered in households. Even very wealthy women did not escape housework, although after midcentury, they were increasingly valued as loving wives and mothers rather than as productive household managers. The economic value of European-American women’s household labor was widely recognized, for few households could survive without the services that women provided. Nevertheless, gender relations within households were hierarchical, subordinating women to their fathers and husbands.

European-American women’s precise legal rights varied from colony to colony, although the shared British common law tradition made most practices fairly similar throughout the 13 colonies. Coverture was the most important legal principle in determining women’s rights and status. Under coverture, a woman’s legal and political identity was absorbed by her husband, who assumed control over his wife along with her property, earnings, and children. Coverture could be mitigated by antenuptial contracts, which allowed women to maintain control over property they inherited or acquired after marriage. But antenuptial contracts required the prospective husband’s consent and were only signed by a minority of wealthy couples. Women whose husbands were absent for extended periods or whose husbands had deserted them or gone bankrupt could petition for “feme sole” status, allowing them to engage in TRADE and control property. Widows were typically guaranteed of receiving a “dower right,” one-third of their husbands’ property; even so, they lacked total control over their inheritances. For example, in most colonies a widow could not sell inherited land without permission from the court; similarly, a husband might choose to make his wife’s inheritance contingent on remaining single. Access to divorce was extraordinarily limited, requiring a legislative act in most colonies. Although the New England colonies permitted “absolute divorce,” which allowed both parties to remarry, these divorces were granted rarely and mostly to men.

The development of colonial economic and legal systems affected enslaved women and Native American women differently. By midcentury, the expansion of SLAVERY dramatically increased the total number of slaves in the Chesapeake and the coastal South, enabling enslaved women to find partners and establish families and kin networks. And although most enslaved women continued to work in the fields, a small percentage worked as house servants, nurses, or midwives. Although these changes improved the quality of women’s lives, they did not mitigate the legal constraints of slavery. Slave marriages were not recognized by law; all children born to enslaved women followed the condition of their mother, regardless of their fathers’ status, and enslaved parents had no legal authority over their children. Native American women saw their status deteriorate over the course of the 18th century, as the growing reliance on European trade upset the balance of power between women and men in Indian communities. European traders sought goods such as skins and furs that resulted from hunting and trapping, work traditionally performed by Native American men; in return, they offered European weapons, clothing, and cooking utensils. When Indian communities became dependent on European goods, women were devalued because their work did not produce tradeable commodities. Women in many tribes, including the Cherokee and Iroquois, also appear to have lost political power during this period, partly because of men’s new economic dominance and partly because Native American-European diplomacy, which was conducted almost exclusively by men, played an increasingly pivotal role in political decision making.

The RESISTANCE movement (1764-75) and the Revolutionary War (1775-83) changed women’s status within both their households and the larger public sphere. Much of the agitation during the imperial crisis was aimed at encouraging resistance to taxation and the undermining of parliamentary authority by boycotting the imported goods that Parliament had taxed. Because many of these goods, especially tea and cloth, were purchased by women for use in households, European-American women’s work became politicized. A woman’s decision to buy tea for her family or boycott it was no longer private and personal; instead, it was a political choice with repercussions that affected her community and even the 13 colonies. Similarly, in order to avoid purchasing British cloth, women began spinning and weaving, tasks that many had abandoned by the 1760s. In the South, slave women were removed from the fields and set to spinning and weaving. And in northern urban areas, many women and children began making cloth at home for sale. Compared to British manufactures, “homespun” cloth was rough and coarse; wearing homespun became a visible badge of patriotism. And during the war, homespun was used not only for regular clothing but also for soldiers’ shirts and blankets. Domestic textile manufacture became even more explicitly politicized when women formed associations, often calling themselves “Daughters of Liberty,” to spin, weave, and sew.

With the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, many Whig and Loyalist women faced new challenges. The absence of their husbands, sons, and fathers left them responsible for managing farms, plantations, and businesses under uncertain and dangerous conditions. Other women became CAMP followers, traveling with the Continental army to provide laundry, cooking, and sewing. Elite urban women formed associations to raise money in support of the revolution. While some women saw these new responsibilities as burdens, others saw them as opportunities. All these activities enlarged women’s interests, turning many into passionate political advocates, broadening their vision of the world, and changing their understanding of themselves. Many women no longer identified themselves only as members of families and communities. Instead, women and men alike began to see themselves as patriots, as participants in a political process that extended far beyond their households and communities.

Revolutionary agitation and a deepening commitment to REPUBLICANISM also politicized European-American households in more abstract ways. Political thinkers had long drawn analogies between political and family structures, arguing, for example, that a king’s right to rule his subjects was analogous to a man’s right to rule his wife and children. In the revolutionary context, the tyranny of Crown and Parliament seemed to parallel the tyranny of an unequal marriage. Revolutionaries aspiring to create a society based upon virtue, in which citizens were bound by affection and respect rather than duty, invoked more egalitarian marriages as the model for a republic. This less hierarchical vision of marriage celebrated husbands and wives as each other’s companions and gave Anglo-American women new stature. Sermons, periodicals, and fiction

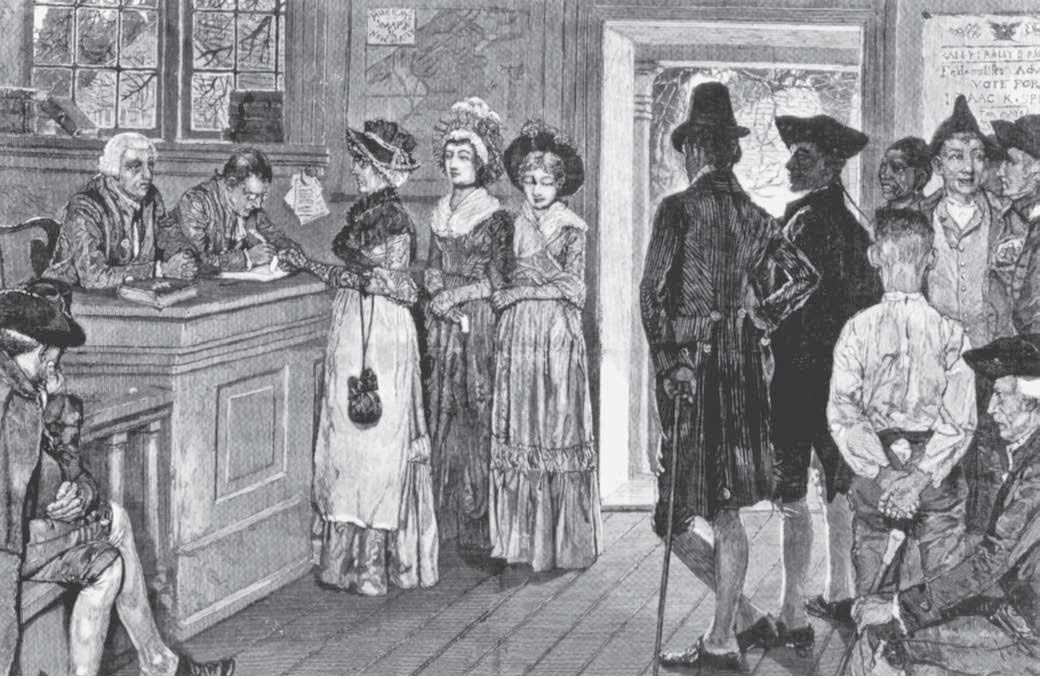

This drawing of women voting in New Jersey depicts the sole instance in revolutionary America when property qualifications for suffrage were defined without regard to sex, from 1790 to 1807. (Howard Pyle Collection, Delaware Art Museum)

Trumpeted the republican woman for her virtue, patience, and industry, qualities that had been valued long before the war. But this literature also singled out new qualities for praise, including reason, education, and civic-mindedness. By emphasizing the virtue and importance of the abstract, idealized wife, politicians and writers necessarily raised the status of real European-American women.

Although the American Revolution did not abolish slavery, enslaved African-American women and men took advantage of the war to pursue freedom. In peacetime, both before and after the Revolutionary War, runaway slaves were disproportionately male; women’s ties to children made escape especially difficult. During the war, however, the British army offered enslaved women and men protection and freedom in return for abandoning their Whig masters, enabling entire families to escape together. And the chaos of war made it possible for groups of slaves to escape regardless of the presence of the British army. Thomas Jefferson later estimated that some 30,000 Virginia slaves ran away over the course of the war, many of them women. Of the 23 slaves who escaped from Jefferson himself, more than half were female. In Massachusetts, groups of slaves, including women, joined together to petition the legislature for freedom. Immediately after the war, a small flurry of voluntary manumissions helped create a free black community in the Upper South. Both during and after the war, slaves throughout the colonies and states pointed out the contradiction between the defense of slavery and the revolutionary ideal of self-determination.

Just as the Revolution did not abolish slavery, it did not change European-American women’s legal status. Nevertheless, the creation of a republic did lead to subtle changes in white women’s status. Although the founders never considered granting women suffrage, they did consider them to be citizens of the nation. Thus, women were entitled to civil rights, which included representation in the lower house of Congress, where legislators were apportioned by a state’s population, male and female alike. From the founders’ perspective, not all citizens were entitled to the same rights; suffrage depended not on citizenship, but on a combination of factors, including gender, race, and property ownership, that excluded many men as well as women from voting. Men who could vote were expected to represent the interests of their dependents, including women, children, and slaves, at the polls. European-Ameri-can women were thus excluded from full political rights but entitled to civil rights such as representation and legal protection. (A few propertied women in New Jersey could vote from 1790 to 1807, when the right of the franchise was deliberately removed from them.) Significantly, this ambiguous status did nothing to challenge the fundamental legal principle of coverture, which continued to restrict married women’s property rights and structure their relationship to the state.

As nonvoting citizens, European-American women were expected to serve the state primarily through their families as “republican wives” and “republican mothers.” The ideology of republican wife - and motherhood incorporated the notions of female virtue that had emerged during the Revolution into a broad program for producing virtuous citizens. The republican wife inspired and encouraged her husband, the voting citizen, to adhere to the highest moral standards both at home and in the public sphere. The republican mother was charged with inculcating republican virtues in her children, especially her sons, from early infancy. Revolutionary Americans thus imbued traditional female roles with new political significance. This new valuation of wife - and motherhood appears to have changed expectations of marriage, at least among the middle and upper classes. Diaries and letters suggest that both women and men began to view marriage as a source of emotional fulfillment and personal happiness rather than as only Christian duty and economic strategy.

These new expectations manifested themselves in divorce proceedings and in new educational opportunities. Following the Revolutionary War, several states enacted legislation to make divorce more accessible, allowing “loss of affection” to be cited as grounds for divorce. Moreover, although divorce remained rare, a greater percentage of divorces were sought and received by women. Indeed, access to divorce was women’s clearest legal gain in the early republic. But these changes did not benefit poor women, who could not afford legal costs. Nor did they apply to women of any class in the South. There, state legislatures retained the right to grant divorce through individual acts of law until well into the 19th century.

Ideals of republican womanhood contributed to a dramatic expansion of educational institutions that benefited middle-class and wealthy women throughout the nation. Because republican virtue demanded reason and intellect as well as affection, increasing numbers of people in the United States committed family resources to finance their daughters’ educations. Hundreds of private female academies opened throughout the nation, offering young women an unprecedented curriculum in reading, composition and rhetoric, mathematics, history, the sciences, ART, Music, and, less frequently, Greek and Latin. But these gains did not extend to poor women or African-American women.

See also MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE.

Further reading: Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: ‘Wo-man’s Sphere in New England, 1778-1835” (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977); Linda

K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980); Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of the American Woman, 1750-1800 (New York: Little, Brown, 1980); Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986); Rosemary Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

—Catherine E. Kelly

World History

World History