G. Fred Asbell

A bow without an arrow is a bent stick, secured in an arc-sort-of-shape. It is unrequited love, unfulfilled potential. Without an arrow, the bow can never fulfill its life's mission... it is the proverbial half-filled water glass. It is only a shaped and bent stick until the first arrow leaps from the string, and then it is a bow.

And, as in life, once the joy of that union has been experienced, and passed... once the marriage is made... expectations beyond exhilaration begin to surface. The blessed thing is supposed to go where you aim it!!! Herein lies the stuff of this chapter.

The marriage of the bow with the arrow is not completely unlike romantic marriage. It is dependent on the right matchup, upon understanding the idiosyncrasies of one the other, and of working together to create the desired effect. Matching the bow and the arrow together, so they function as a single cohesive unit, is the beginning and end of accuracy with all types of archery equipment. Unfortunately, traditionalists sometimes walk right by that. Sometimes accidentally, because it is not always understood. But probably more often it is our need to escape the trappings of modern equipment and technology which causes us to also reject anything that smells of precision and observation. That is a mistake.

I often hear fellas say "... that's why I quit shooting all that other junk, 'cause 1 didn't wanna do all that crap." I understand all of that, believe me I do. It is such a common feeling among those who have chosen the traditional way. But, when you step into the woods with a bow and arrow in your hand in pursuit of an animal, regardless of whether you are shooting the most primitive bow ever built or the most modern piece of high-tech machinery, you have the responsibility to kill that animal quickly and cleanly... and nothing else is acceptable, under any circumstances.

Part of the added challenge of traditional equipment, part of the fun, is in learning to shoot the equipment well... to make the arrows go where you point them.

As a group, we bowhunters have always been preoccupied with the bow itself. I think that is particularly true with traditional bowhunters. For the most part, our bows are what set us apart from other archers. The arrows can also be very different, but they are not the thing that identifies the traditionalist. Even though we've heard it hundreds of times, it bears repeating, because it is one of those things that is often said, sometimes heard, and rarely soaked up... the arrow is the most important part of the bow and arrow shooting equation. The finest bow in the world will shoot very inaccurately with unmatched, cheap arrows. On the other hand, a bent willow stick fresh from the river bank, with a piece of binder's twine for a string, will shoot precisely if it is matched with a good, straight, precision arrow.

IT ALL STARTS WITH THE ARROW

Matching the arrow to the bow is more difficult with the self-bow. It is more difficult than matching arrows to modern composite longbows with an arrow shelf cut-out, which in turn is more difficult than recurves. It all has to do with the degree to which the bow is centershot. The more centershot, the more simple is the arrow matchup. The less centershot the bow, the more difficult arrow matchup becomes, and the more important it is to accuracy.

When we say a bow is centershot, or not centershot, we are talking about whether the bow is cut in far enough at the arrow rest to allow the arrow, when

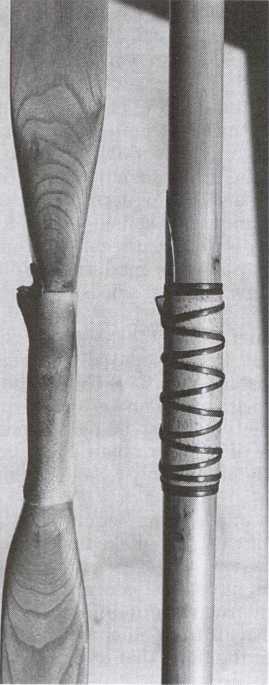

The bow on the left, a modern fiberglass recurve, is centershot; the other two are not. The Osage bow in the middle has a narrow, deep handle, in part so the arrow can pass closer to the center of the bow. The widest part of the pew longbow, at right, is at the handle. With properly matched arrows, all three can shoot with precision.

Shot, to pass the bow at about its left to right center, (making it center shot), or to the left of center (non-centershot). This is assuming a right-handed shooter. In general, self bows do not have a sight window cut-out and are not centershot. Because of this, the self bow is more difficult and more critical of bow and arrow matchup than any other type bow. But, I would add here for clarification that this difficulty has only to do with the centershot feature. A compound bow without any sight window cut-out would be every bit as difficult to set up... probably much more so.

When an arrow is shot, it goes through what is known as the archer's paradox. Here's what happens: the force of the string upon release begins driving the arrow forward. That force (the poundage of the bow) causes the arrow to first bend inward against the side of the bow, then the arrow flexes back in the opposite direction, then back to the original bend, and so on. It is a left to right fish-tailing that takes place every time an arrow is shot from any bow. An arrow shot from a centershot bow does much less of this fish-tailing business than does a bow which is non-centershot (your bow, for example). The reason for this is that the string is basically pushing the arrow straight forward from a centershot bow, and since the arrow is straight in front of the string, there is minimum contact with the inside of the sight window, although there is some. With the non-centershot bow, the arrow is not fully lined up ahead of the string, but is pointing off to the left (for right handed shooters). The string drives straight forward upon release, shoving the arrow into the side of the bow. The side of the bow (from where the arrow is touching) prevents the arrow from going straight ahead, and thus the arrow flexes considerably more to get past this obstruction.

This is why the non-centershot bow is more critical on arrow matchup. When you shoot such a bow, your arrow must go through considerably more acrobatics than does an arrow from a bow with more centershot, such as a modern fiberglass longbow, a recurve, or a compound. And because of this, your arrows must be matched to the bow as closely as possible before you can develop any level of consistency and accuracy.

The critical thing to understand here is that if the correctly spined arrow is used in this non-centershot bow, the arrow will actually bend around the bow and go straight ahead, just as though the bow were actually centershot. You may want to read through the above again, because what it says is that if you shoot the correctly spined arrow from your self bow, it will shoot just as true and straight at where you are looking as it will from any fancy centershot bow.

As I said earlier, the tendency is for traditional archers to want to pay less attention to doing things just right, when in fact, they really do need to pay more attention to it all. Sorry.

Without exception, you will need to shoot a lighter spined arrow from a non-centershot bow. And I know that you often hear you should shoot a heavier spined arrow from a non-centershot bow. Trust me. Lighter spined is the correct choice (I said lighter spined, not lighter physical weight). Again, this is because the non-centershot bow forces the arrow to go through the bending of paradox to a much greater degree. And this means that a lighter spined arrow is required to allow the additional bending. If we consider the modern composite longbow.

Which has some sight window cut out, and is more centershot... more that a self bow, and less than a centershot bow... we see that it will have different spine requirements than will the self bow, because it is "more centershot." You match the spine of the arrow to (1) the weight of the bow, (2) the weight of the arrowhead. These two in combination determine the correct arrow for your bow.

Consider this: if your self bow is 3/4 inch wide at the handle, and mine is 1 inch wide, we will need different arrows, even though our bows are the same weight. This is because my wider handle is forcing the arrow to move farther from the vertical center line of the bow and the thrust of the string than your narrower handle. It would not surprise me if the popularity of the stacked limb longbow over the flatbow was partially a product of its narrower handle section.

There is no magic formula for determining what arrow is correct for your bow. It can only be done by going out and shooting and watching to see what happens. You might find an arrow shoots perfectly from a given bow, and I might not be able to shoot the same arrow from that bow for love nor money. Sometimes having a friend stand behind you to watch your arrow in flight is a help. I stand up on a chair, slightly above and behind the shooter, and that gives me a perfect view of the arrow in flight.

Continuing with this arrow thing; you also need to consider that because your bow is non-centershot, and thusly your arrows are going through more paradox, arrow straightness is more important than it is with other bows. And I know you probably didn't want to hear that either. I am convinced that a handful of somewhat crooked arrows will shoot a baseball-sized group from a centershot bow, and a dinner plate-sized group from a non-centershot bow. Your arrow is flexing and whipping left to right as it comes from your non-centershot bow to a much greater degree than it is with a centershot bow. Any imperfection in the arrow itself will be magnified by this exaggerated motion. This is why broadhead selection is more critical with longbows and self bows... an air foil is created on the end of the arrow by the broadhead itself. This oversized object out on the end of the arrow multiplies the effect of the arrow paradox and can possibly even cause the arrow to go careening off in a wind plane.

Sometimes just the additional weight of the broadhead on the end of the arrow messes things up. That weight on the very tip of the shaft serves to magnify the left to right action of the arrow. A 125 grain broadhead might shoot fine, but a 165 grain head in the same design might cause your arrow to do all kinds of crazy things.

This whole non-centershot, additional flexing, arrow straightness thing is why traditional archers typically must shoot bigger feathers. The bigger the feather, the more air it grabs, and the quicker the arrow stabilizes and goes straight forward. Big, helically applied feathers will cure lots of ills in arrow matchup. And if you don't want to use helical fletching, then angle them slightly. The idea is to get the arrow spinning as quickly as possible, and either helical or angled feathers will do that better than will a straight fletch. The formula is based on total feather surface. So look at how much actual feather... length and height... you have to determine what is best. Three 5 inch die-cut feathers, 5/8 inch high, are not going to stabilize like three trimmed or burned feathers, 5 1/2 inches long by 3/4 inch high. The 5 1/2 x 3/4 inch, which is what I use.

Has almost 3 1/2 square inches more surface area. In general, feather height is more important than length. I feel that each 1/8 inch difference in height in the equivalent to at least 1/2 inch in length. It doesn't actually need to be mathematically figured. Just use the amount of feather required to straighten up your arrow. I would add, however, that I've yet to see anyone who was getting decent arrow flight from a self bow with three 5 inch die-cuts.

You must test shoot each arrow from your self bow. This applies even if you are using the finest store-bought arrows available, built by the world's finest fletcher. If you are hand-spining your arrows by feel, you should most definitely test shoot each arrow repeatedly. The same is true tenfold with broadheads. Each arrow should be shot several times, and only those which shoot consistently should be considered as acceptable for taking to the deer woods.

World History

World History