At the beginning of the 20th century, art was undergoing a process of transformation. Traditionally, art was expected to serve as a civilizing and inspirational force, a carryover from the Victorian ideals of the previous century. A new generation, however, struggled to redefine the role of art. Many artists were impatient with the standardized, approved academic form and struggled to be recognized as American artists, rather than artists in America. These artists worked against cultural norms of the time.

American high culture valued art that exhibited the traditional ideals of discipline and restraint, not artistic individualism and freedom. American neoclassical artists Kenyon Cox and Abbott Handerson Thayer worked within these traditional academic forms. In order to avoid overt personal expression, they used the standard models of art: smooth-painted surfaces, detailed execution, crisp outlines reminiscent of the French-derived neoclassical art. Drawing on images and symbols of the past, Cox and Thayer portrayed order and harmony. They believed in the civilizing power of art, creating work that was academic, mythical, and standard in form. Architecture of the time also followed neoclassical standards. Many monuments, sculptures, and murals were executed for public buildings during this period.

Society portraitists used their subject matter to focus on the private experience and personal gesture, rather than the classical imagery and controlled style of neoclassical art. In illustrating the domestic world of refinement, portraitists chose romantic idealism over honesty or duty toward the public world. John Singer Sargent’s work embodied the English and German tradition of society portraiture. Other artists such as Cecilia Beaux, John White Alexander, and Charles Hawthorne took their cues from Sargent, composing a world of refined elegance distanced from the harsh reality of contemporary life. As artists, they were “safe” in a technique removed from actual experience. Thomas Eakins, a painter from Philadelphia, along with his pupil Thomas Anshutz, began to illustrate the change from romantic idealism to realistic and more contemporary life portraits. Eakins’s portrait, The Thinker: Portrait of Louis N. Kenton, combined thoughtful pensiveness with native realism, illustrating the ambivalence of an individual contemplating an uncertain future. In a similar style, Anshutz’s portrait, A Rose, reflected the upper-class world at the turn of the century. It portrayed a reflective, confident woman, something modern America would confront in the near future. Anshutz’s work laid the foundation for the urban realists who would later emerge in New York under the leadership of his pupil Robert Henri.

Henri was a realist painter who observed the activity around him. Unlike his predecessors, his scenes were almost exclusively urban. He also changed the focus and function of art. He believed that art must be a record of daily life with no glossing over its harsher aspects. The academic, mythological scenes of the past had no part in his art. The motion and activity of the urban streets were where Henri’s perspective lay.

Exhibition opportunities for American artists were controlled almost exclusively by two New York-based institutions—the Society of American Artists and the National Academy of Design. When the two organizations merged in 1906, the jury’s exclusion of works by several of Henri’s friends, and two of his own works, provoked a controversy. Henri, a man who believed that art must reflect the spirit of the time and nation, became so frustrated by the lack of artistic vision, that he and his colleague John Sloan arranged for their work to be exhibited at the MacBeth Galleries. In February 1908, “The Eight” opened the Exhibition of Paintings. Known as the AsHCAN SCHOOL of artists, this group had enough experience as journalists to know how to market themselves and promoted their ideas of independence and freedom along with a distinctly American point of view.

In an attempt to address the lack of exhibition opportunities and patronage that artists were facing, Robert Henri and his colleagues organized the 1910 Independents Show. It had only limited success, because of its stipulation that any artists applying to the show were not allowed to submit paintings to the National Academy that year. The group then began discussing the possibility of exhibiting a more ambitious show of American art. In January 1912 a group of 25 artists formed the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. The relatively conservative J. Alden Weir was selected as president. Unable to find an exhibition site after a year and faced with the resignation of Weir as president, the group persuaded Arthur B. Davies to take over. Davies satisfied both conservative and realist factions. He sought to break from the well-established American aesthetic provincialism and successfully pushed for the association to include European art in its exhibition.

The International Exhibition of Modern Art opened its doors on February 17, 1913, at the armory of the New York Guards Sixty-ninth Regiment. Popularly known as the Armory Show, the exhibition originated out of artists’ concerns over the lack of exhibition opportunities and patronage that American artists faced. The impact of the show was incredible, closing the gap between American and European standards of reference. The reaction of the press elevated the show to a position of prominence by labeling its unconventional inclusions MODERNISM. Thus, a foundation for modern art was established, giving it at a stature more equal to that enjoyed by European art.

Other traditional artistic forms of the past were giving way to artistic expression, and they reflected the rapid impact that industrialization had on American culture. Artists began to draw on their experiences and in ways that were seen in the American urban landscape—where the power of American modernity opened up. Artists used the city to express what it meant to be American. Symbols of progress and futurity were the urban architecture of skyscrapers, electric streetcars, automobiles, elevated trains, and subways.

One of the first artists to use this urban landscape style was Alfred Stieglitz, through the medium of photography. Other artists also turned their attention to the urban landscape. Childe Hassam used New York street scenes, skyscrapers, and bridges to achieve the idea of mood and nature, and artists like Jonas Lie responded to the powerful force of American urban life. He painted a scene of industrial steamers at work on the river, their billowing clouds of steam serving as a metaphor for American prosperity and power. John Sloan’s painting Sunday, Wo-men Drying Their Hair used scenes from the lives of working-class women, revealing his understanding of their freedom. In his painting, they appeared unconfined by the more rigid codes of conduct and behavior expected of middle-class women.

Other urban scenes reflected the growing forces of American social reform, where artists used their art as a tool for social change. Abastenia St. Leger believed artists had a duty to be responsible to others, and her 1913 sculpture of a young woman being auctioned into prostitution was reproduced on the cover of The Survey magazine. By the 1920s, artists were engaged with questions concerning issues such as WOMAN SUFFRAGE, BIRTH CONTROL, racism, Freudian analysis, and SOCIALISM.

Forum magazine sponsored the Forum Exhibition of Advanced American Painters in order to advance the public’s understanding of abstract art. The realists also sponsored an exhibition at the Grand Central Palace in New York on April 10, 1917, to encourage the country’s enthusiasm for American art and the realist agenda. Unfortunately, public attention centered around a dispute over whether or not the organizers would accept Marcel Duchamp’s controversial Fountain into what was supposed to be an unjuried exhibition. Another reason for the failure of the show was that four days before it was scheduled to open, America declared war on Germany.

The wartime prosperity and the proliferation of new technology and machines allowed Americans to raise industry into a national religion. Communication transformed public life. Domestic machines converted American society into what was thought to be a more efficient, hygienic, mechanized environment. The impact of machines was so pervasive that many people referred to it as the machine age. Businessmen and engineers became the predominant icons of the era.

Technology associated with the United States penetrated the American consciousness in the 1920s. Precision-ism was the American version of the “call to order” that swept Europe after the war. Initially labeled cubist, preci-sionism gave geometric lines to architectural and machinist subjects and expressed stability and permanence. Charles Demuth and Preston Dickinson were two artists who focused on exploring abstract arrangements of flat, uncomplicated shapes without giving up recognition.

The United States became more isolationist in the twenties, reflecting a period of contradiction and excess. Opulence found expression in art through decoration and adornment. The discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb brought the popularity of Egyptian art to the United States. The carefully organized patterns of Art Deco built upon the popularity of technology and Egyptian art, mixing the ancient with the modern. Artists Florine Stettheimer and Paul Manship expressed the deco movement with their highly ornamented and stylized motifs. This movement drew from earlier, more orderly and tranquil times, while incorporating materials and inventions of the modern world.

Discussions about identifying what was uniquely American became more commonplace, spreading along with the nationalist fervor in the 1920s. Americans wanted to identify what was uniquely American. Stuart Davis was an artist who combined modernism with his vision of contemporary America. He condensed contemporary American culture through collage-like painted images, incorporating themes of jazz, radio, movies, consumer products, and ADVERTISING. Davis restrained the idea of three-dimensional space and provided visual movement by adding dots, stripes, dashes, and grids. His street scenes also controlled dimension, but they portrayed a particular place. Davis’s work illustrated the fascination art had for the visual expressions in advertising.

Themes of art shifted along with American demographics, going from the rural to the urban. American scene painters believed that realism was an attitude toward life and humanity. Edward Hopper’s work focused on melancholy and isolation, derived from his sense of a loss of values and an abandoned way of life. He identified with an American past that had been rendered obsolete and transformed it into universal and timeless commentary on the human condition.

The search for American identity also was evident in the Harlem Renaissance, which began with the migration of a new generation of African-American artists to Harlem. It had as its consequence, an attempt to cultivate racial tolerance by promoting the cultural accomplishments of African Americans. Concentrations of African Americans in cities provided a new sense of self-determination and opportunity. The incorporation of African art and so-called

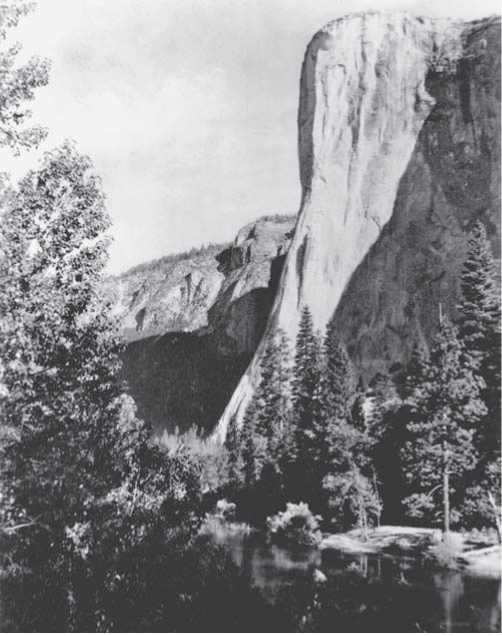

"El Capitan in the Yosemite Valley," by Ansel Adams (Library of Congress) primitive culture integrated modernism with international themes.

American abstract art flourished in the 1920s. Those interested in pursuing art outside the realism genre were encouraged by new galleries and patrons that emerged after the 1913 Armory Show. Alfred Stieglitz ran one of those galleries. In 1925 he opened an exhibition called the “Seven Americans,” and nine months later he opened the “Intimate Galleries.” His intent was to support the work of American artists committed to the creation of a national culture, and he considered the focal point of that culture to be the land. These artists viewed mechanization as psychologically damaging and saw nature as a means for spiritual wholeness.

Artists such as Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and Oscar Bluemner created organic shapes, drawing out nature to its essential quality in order to translate its mystical essence into powerful abstract forms. The transcendental connection is apparent in Dove’s work. He had a complex personal style that worked with nature and modern movement in his painting. O’Keeffe’s geometrically inspired botanical themes represented expressive, luxuriant visions of nature. Marin saw the architecture in nature very much like the architecture of urban areas, referring to the pushing and pulling of natural forces. Bluemner reduced landscape motifs to bold color planes, seeing color as a “visible creative force.”

Artistic debates over which type best represented American national identity continued. But on October 29, 1929, the stock market collapsed, and along with it went the sense of prosperity that Americans had been experiencing. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s most urgent duty was to find relief and promote recovery of the nation’s economy. Art and its institutions continued to change in response to the growing economic crisis and the political message of the New Deal.

Further reading: Abraham A. Davidson, Early American Modernist Fainting, 1910-1935 (New York: Harper and Row, 1981); Henry Geldzahler, American Painting in the Twentieth Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1965); Barbara Haskell, The American Century: Art and Culture, New York, 1900-1930 (New York: Norton, 1999); Barbara Rose, American Fainting: The Twentieth Century (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1986).

—Marcia M. Farah

World History

World History