A twenty-first-century observer might guess that the pogrom of 1881 would have put a stop to continue Jewish migration to Kiev, or that the official restrictions on Jewish residence, which under some bureaucrats were enforced very harshly indeed, would have been a deterrent for many. But Jews continued to settle in Kiev. Of the hundreds of interactions between Jews and Christians that took place every day in the city, very few seem to have been openly hostile. Surely some fraction of such incidents would have made their way into the press and memoirs, but those sources contain very few descriptions of everyday animosity. It seems unlikely that they were so common as not to be considered worthy of mention.

The 1905 pogrom was not only an outburst of antisemitic violence; it was a symbolic reconquest of Kiev from the "seditionist Jews" whose influence, in the minds of many Christians, had grown far too great in the city. The "patriotic" demonstrations on the main thoroughfares of Kiev that took place throughout the pogrom were a show of force and strength; they were meant to broadcast a message: we control the city. The violence and looting were yet another way of saying, albeit in a less civilized manner, that the "true Russians" and the "native population" were the only people who had the right to be in Kiev, and Jews, their property, and even their lives were all "rightless"—what in Yiddish might be called hefker. The inaction of the authorities, and the lack of self-defense among Jews, only strengthened this argument.

After the 1905 pogrom, however, Jewish insecurity grew to unprecedented heights. Now Jews not only feared being caught without a residence permit and being expelled from the city, but they also dreaded the next deadly riot. An observer remarked in 1912 that Kiev's Jews, always haunted by the specter of pogrom, "lived with a sword hanging over their heads."183 What would spark the next pogrom? Whether it was Passover, the anniversary of Stolypin's assassination, or even Election Day, their enemies were sure to find a propitious time to attack. The numerous near-pogroms that occurred during these years were fictionalized poignantly by Sholem Aleichem in his novel The Bloody Hoax (Der blutiger shpas), which described wealthy Jews taking out foreign passports to ensure a quick escape, prosperous middle-class Jews hocking furs and jewels at the city's pawnshops, and poor Jews rushing to the train station only to sit waiting with thousands of others like them until, finally, the governor issued a declaration banning a pogrom.184 For all their talk of defending Jewish national pride, self-defense groups such as those organized by the Bund had little chance of success in the face of official repression and internal division.

Nonetheless, Kiev continued to be a magnet for Jews. Perhaps Kiev's Jews so needed (or wanted) to remain in the city, despite all the problems, that they learned to downplay the gravity of their situation, as in their reported reaction to the expulsion of 1910: "The affair was not as terrible as the newspapers make it out to be."185 The article, one of a series in Haynt entitled "The Truth about Kiev," added that this opinion was expressed by "all kinds of Jews in Kiev, from the communal leaders to the people in the street." In another article in the series, the correspondent wrote that to understand the importance of Kiev for Jews, one had to understand its geographical and economic role in the region. When Jews were restricted from going to a city outside the Pale like Moscow, they figured out a way to do it through agents. But, he explained, it was different with Kiev: it was full of Jews, and right in the middle of the Pale—indeed, it was the heart and nerve center of the entire region: "Kiev is where merchandise is bought and sold; the seat of the district court and all of the administrative and governmental bureaus that almost everyone has need of; . . . Kiev is where you find a good lawyer, and where you go when you are sick. . . !’ Kiev was a hub for the sugar industry, for import-export, for trade in real estate and forested properties, and was a port handling tens of millions of rubles of merchandise. In short, "without Kiev, a Jew is lost."186

FIGURE 1.1. Lazar’ Brodsky. Photograph courtesy Leonid Finberg and the Kiev Institute of Jewish Studies.

FIGURE 1.3. Max Mandel’shtam.

Photograph courtesy Leonid Finberg and the Kiev Institute of Jewish Studies.

FIGURE 1.2. D. S. Margolin. Photograph courtesy Leonid Finberg and the Kiev Institute of Jewish Studies.

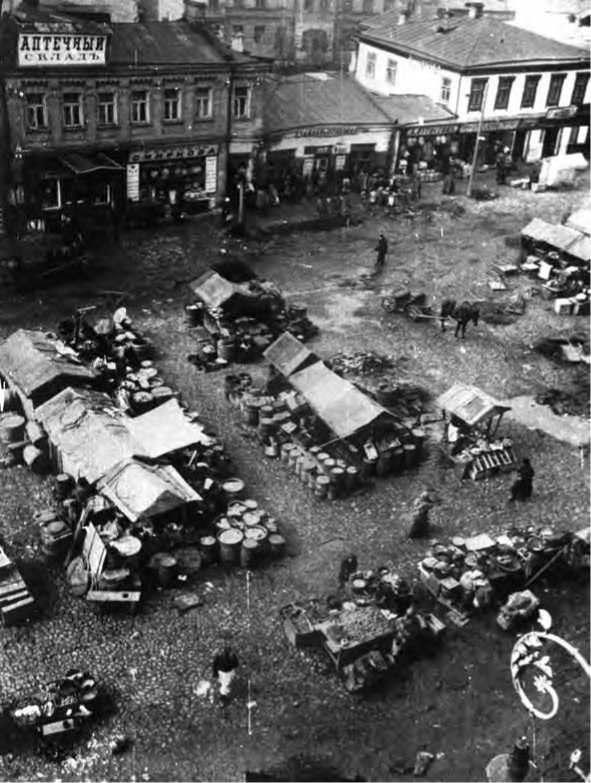

FIGURE 1.4. Evreiskii bazar ("The Jewish Bazaar"), also known as Galitskii Market, undated photograph. Courtesy Leonid Finberg and the Kiev Institute of Jewish Studies.

FIGURE 3.1. Studio portrait of the Rutov family, 1911: Mordkhe, who ran a hardware store, his wife Eta Bella, and their sons Iosif (r.) and Aleksandr. From family collection of Viktor Khamishon. From the Archive of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York (RG120, Russia II, folder 145.13).

FIGURE 3.2. Evreiskii bazar ("The Jewish Bazaar"), also known as Galitskii Market, 1905.

Courtesy Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (Ru 441, no 49). Original in TsentraVnyi derzhavnyi arkhiv kino-foto-fonodokumentiv, Kiev.

FIGURE 3.3. view of Podol, ca. 1890-1900. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

FIGURE 3.4. view of Podol, ca. 1902. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

FIGURE 3.5. view of Kreshchatik, ca. 1890-1900. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

FIGURE 3.6. Crowd in front of City Hall (Duma), 1905 or 1906. Photograph taken as part of relief mission of the Russo-Jewish Committee in the wake of the pogroms of 1905. Courtesy University of Southampton Special Collections (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ 22IAI7).

FIGURE 3.7. House on Zhilianskaia street with windows smashed and debris in front of building as a result of the 1905 pogrom. Courtesy University of Southampton Special Collections (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ 22/A/7).

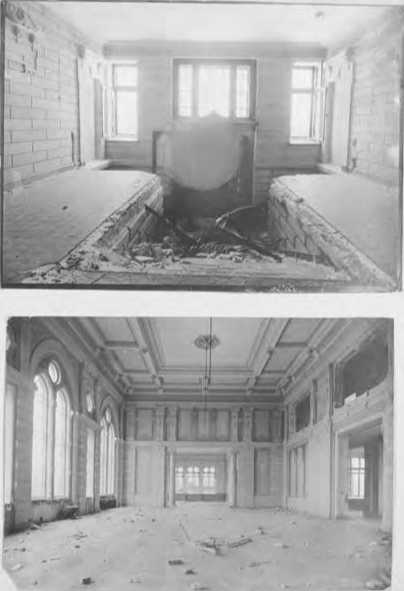

FIGURE 3.8. Entrance hall in house of M. B. Gal’perin showing destruction after 1905 pogrom. Courtesy University of Southampton Special Collections (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ 22/A./7).

FIGURE 3.9. Salon in house of M. B. Gal’perin showing destruction after 1905 pogrom.

Courtesy University of Southampton Special Collections (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ 22IAI7).

FIGURE 3.10. Destruction inside Brodsky School, 1905. Courtesy University of Southampton Speeial Colleetions (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ22/A/7).

FIGURE 3.11. Crowd of peasants marching with flags and portraits of the tsar, 1905. Courtesy University of Southampton Special Collections (MS 128, Papers of Carl Stettauer, AJ 22IAI7).

FIGURE 3.13. Mendel Beilis with his family, ca. 1913. Courtesy of YIVO Institutefor Jewish Research (collection MG).

World History

World History