Russian history holds that Russia's first settlers were Slavic tribes migrating from the west in the fifth century. In the ninth century the Slavs were invaded by the Varangians, Scandinavian Vikings, who followed the Russian rivers to trade with Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. One group of Norsemen, called the Rus, established trading posts at Kiev and Novgorod in Slav territory. Kiev was the seed out of which the first Russian kingdom grew. In AD 989-90, soon after the grand prince of Kiev, Vladimir the Great (980-1015), embraced the Byzantine Orthodox Christian faith, the Kievan pagan state was forcibly converted to Christianity. From Kiev, the Eastern Orthodox faith spread to the other Russian principalities.

Thenceforth, until the sacking of Russia by the Tatars in the thirteenth century, the infant Russian state - which was little more than a scattering of principalities - continued to extend its power and foster its relations with Byzantium.

Central to the story of Russia's past is the influence of war, want, struggle and suffering. Russians are acutely aware of the burden of the past.

Old Russia [Stalin once remarked] ... was ceaselessly beaten for her backwardness. She was beaten by the Mongol Khans. She was beaten by the Turkish beys. She was beaten by the Swedish feudal lords. She was beaten by the Polish-Lithuanian gentry. She was beaten by Anglo-French capitalists. She was beaten by the Japanese barons.1

Not all Russia's suffering has come from other hands. Listen to the Russian poet, Yevgeny Yevtushenko (b. 1933):

She was christened in childhood with a lash, torn to pieces,

Scorched.

Her soul was trampled by the feet, inflicting blow upon blow, of Pechenegs,

Varangians,

Tatars,

And our own people -

Much more terrible than the Tatars.

From these roots stem Russia's melancholia, paranoia, passivity, xenophobia and national self-pity.

For 250 years, from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, the Russians made war against the Tatars2 (the Mongols and their Turkic-speaking allies). The Mongol yoke was a catastrophe of such proportion that Russians have never forgotten it. Only by submissively paying tribute and fighting for the Mongol Golden Horde were they tolerated. Several times Moscow was overrun and destroyed. A Russian victory over a Mongol army at Kulikovo on the Don in 1380 - the first time that the Russians had beaten the Tatars - is a hallowed day in Russian history.3 Kulikovo signalled the eventual waning of Mongol power and the waxing of the Russian states. Yet it was not until 1480, when Ivan III refused to kiss the stirrup of the khan, that Russia broke the vice-like grip of Mongol rule. It is thought that by then the Mongols had killed at least one-tenth of Russia's population and had deported many thousands into slavery.

When in 1453 Constantinople perished at the hands of the Ottoman Turks, it was taken for granted that Moscow, the largest of the Russian principalities, would become the centre of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Russian authority. (Kiev had been destroyed by the Mongols in 1240.) When Ivan III, the Great, came to the Russian throne in 1462 - by which time Russians had successfully repulsed invasions by Lithuanians, Poles and Swedes - he emphasized Russia's connection with Byzantium by declaring himself the successor of the last of the Greek Byzantine emperors. He adopted as his insignia the Byzantine doubleheaded eagle. In 1471 the rival principality of Novgorod was subdued by Moscow; in 1485 Tver suffered the same fate; the fall of Pskov, Riazan, Yaroslavl and Rostov followed.

Underpinning Ivan III's rule was the expansion of the gentry military cavalry, which became the corps of his army and reduced its dependence on the feudal lords. He also introduced the practice of recruiting infantry from the towns. Although his communications were blocked by Swedes, Poles and Turks, he was able to obtain English weapons by way of Archangel on the White Sea.

In 1492 Ivan III began Russia's westward expansion by invading Lithuania and reaching the coveted harbours of the Baltic Sea. The push to the sea - a traditional Russian goal - had begun in earnest. Before Ivan III's death in 1505, by conquest or diplomacy, the unification of modern Russia had taken place. By the time Ivan's son Vasili III died in 1533 a nation had been born. In 1547 the Kievian tradition of a confederation of equal sovereign princes gave way to the absolute rule of Tsar Ivan IV, the Terrible (1530-84), who was crowned Russia's first tsar. His 51-year reign was marred by tyranny and terror. He struck and killed his eldest son in a fit of rage; whole communities remotely suspected of opposing him were wiped out; thousands of citizens of Novgorod were put to death. As his reign progressed he took all power from the assembly of boyars, the nobles who had advised him, and ruled single-handedly and dictatorially. In 1560, on the death of his wife, he is thought to have become increasingly mad.

In the protracted and exhausting Livonian War of 1557-82, against Lithuanians, Poles and Swedes, Ivan IV seized the ports of Narva and Dorpat. In 1578, in the on-going struggle between Russia, Sweden and Poland, Russia was defeated. At the end of 1610, because of renewed Polish and Swedish invasions, Russia had neither a government nor a tsar. In 1613 the crown was offered to Prince Mikhail Romanov (the Romanov dynasty was to last until 1917). In the early decades of the seventeenth century Russia was assailed by the Swedish king, Gustavus II Adolphus (reigned 1611-32), a leading military innovator. The struggle in the west and the north continued indecisively.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Russia also fought its way eastward against the Mongols and the Turks (Map X). In 1552, during the reign of Ivan IV, it seized Kazan, a Muslim Tatar stronghold on the middle Volga. (St Basil's Cathedral was built in the Red Square to celebrate the victory.) With the fall of Kazan the way was opened to cross the Urals into Siberia, rich in furs and minerals. By 1700 Europeans were the majority there. Ivan's triumph also led to increased trade with Persia. Astrakhan on

The Caspian Sea was taken in 1556. Yet Russian expansion eastward had constantly to be defended from the rear. In 1571 Moscow was once more sacked by an invading force of Crimean Tatars.

For the remainder of the sixteenth and the whole of the seventeenth centuries, Russia colonized the valleys of the Dnieper, the Don and the Volga. With control of the entire Volga region, Russian expansion to the southwest, as well as the east, was assured.

With the accession of Peter I, the Great (b. 1672, reigned 16821725), Russian fortunes changed dramatically. Peter was the first Russian sovereign to try to westernize his country and end its near-isolation. He recognized western Europe as militarily and economically superior, and culturally more advanced. After his travels in the west in 1697-8, he returned determined to change Russia's oriental outlook. Peter's courtiers were ordered to adopt European dress; the seclusion of upper-class women was ended; the Church was made subservient to the throne. Dutch, German and British technicians were induced to come to Russia to assist in its naval building and its earliest mining and manufactures. Symbolically, in 1703 Peter transferred Russia's capital from Moscow to St Petersburg on the Gulf of Finland. At this time, Russia was the most populous state in Europe next to France.5

Like his contemporaries, Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia and Louis XIV of France, Peter geared the state to the needs of the military. He built a navy and reorganized the army. Having lost Narva to the Swedes in 1700, he is said to have rebuilt his army in a single year. His two great victories in the Great Northern War (1700-21) over the Swedes at Poltava in the Ukraine in 1709, and on the Baltic in 1721, ended Swedish supremacy. Russia could now trade directly with the maritime powers of the West. Gustavus II Adolphus' boast that Russia could not 'sail a single ship into the Baltic' had come to naught. The Peace of Nystadt in 1721 began Russia's rise as a European power.

Peter is remembered for having freed Russia of the dead weight of the past; for having expanded Russian territory and power; for having abolished the patriarchate; and for allowing the education of Russians abroad. He is also praised for his leadership, his will, his courage and his inexhaustible energy. He was willing to learn from both East and West. Less favourable memories stem from his disregard of Russia's national traditions; for his introduction of western manners and ways; for his subjection of the Orthodox Church to the state; and for his tyranny and brutality.

In one day in October 1698 he had 250 suspected dissidents put to 'a direful death' (roasted alive). He also had his own son tortured to death.

Peter's objective - expansion at the expense of Sweden, Turkey and Poland - was furthered by Catherine the Great, who came to the throne with the help of British gold. Having helped to terminate the Seven Years War (1756-63), in which Russia had joined Austria and France against Prussia and Britain, Catherine was able to turn to other foreign challenges. Under her rule Russia came to be feared by the Turks on the Black Sea as well as by the Swedes on the Baltic. Catherine's wars against the Turks (1768-72 and 1787-92) eventually brought the northern shores of the Black Sea under Russian control and strengthened her position in the Caucasus. The Crimea was annexed in 1783. Odessa was founded in 1794 as a southern outlet for Russian trade. In 1772, 1793 and 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia. Meanwhile in 1780, Catherine, determined to play a leading international role, had offended both Britain and Spain with her Declaration of Armed Neutrality, which supported the efforts of the neutral countries to protect their merchant shipping. It became the cornerstone of a second League of Armed Neutrality (between Russia and Sweden, October 1799) to protect neutral seaborne trade against British and French seizures.

The longer Catherine reigned, the more autocratic she became. Beginning as a progressive and benevolent ruler, she reversed her liberal policies after a peasant revolt in 1773. After that any challenge to her authority was crushed. The French Revolution with its reign of terror, and the execution of Louis XVI, ended her enchantment with Enlightenment ideas and those who espoused them.

Russia played a leading role in European power politics during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era. It joined the other European powers in their efforts to impede French expansion, which threatened Russian interests in the Balkans, the Turkish Straits and Poland. In 1798 it successfully intervened against France in the eastern Mediterranean. Austrian-Russian forces fought the French in Italy. Between 1805 and 1807 under Tsar Alexander I (b. 1777, reigned 1801-25) it fought Napoleon in central Europe. At the same time it fought the Turks (1806-12) and the Persians (1804-13). In 1807 it made a truce with Napoleon that divided

Europe into Russian and French spheres of influence. Also in 1807 in a war with Sweden, it annexed Finland as a grand duchy within the Russian Empire. In 1812 it repelled a French invasion in 'the first fatherland war', which was fought to decide who would be supreme on the continent: France or Russia. Napoleon's efforts to conquer Russia and drive the Russians into Asia failed.6 Napoleon's aim of a united Europe with France at its head remained a dream. Russia headed the continental powers which overthrew Napoleon in 1814. Its influence at the peace settlement in Vienna, which followed Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, brought Russia to the peak of its power under the tsarist regime. The defeat of the French left a vacuum of power in western Europe, which Russia proceeded to fill. It played a leading role in the Congress of Vienna, which established a European order able to avoid a general conflict in Europe for a hundred years (Map VII). Its further westward expansion, however, was impeded by Prussia and Austria.

In 1826 Russia went to war with Persia over Armenia. In 1827 it helped to destroy the Ottoman fleet at Navarino Bay, which brought to a head Russian-Ottoman conflicts in the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Black Sea, and led to war in 1828-9. By the mid-century Russia was at war again in the Crimea (1853-6). Earlier, in 1851, on the pretext that it was exercising its supposed rights as the guardian of the Orthodox Church, Russia had occupied the Turkish-controlled Danubian provinces. France had intervened as guardian of the western Roman Catholic rights. The British, unimpressed by the 'quarrel of monks', but equally alarmed at Russia's invasion of European Turkey and its growing power in the Black Sea, supported France.

In October 1853, encouraged by Britain and France, Turkey declared war on Russia. A month later Russian armoured vessels, using new shell guns, annihilated a Turkish squadron of wooden battleships off Sinope in the Black Sea (Map X). Although it was the Turks who had started the Crimean War, the 'Massacre of Sinope' did much to enrage public opinion in Paris and London. The cry went up to rid Europe of Russian tyranny. To prevent Russia from subduing Turkey and seizing the Dardanelles (Turkish Straits) which gave it access to the Mediterranean, and which had been closed to Russian warships since the international Straits Convention of 1841, British and French warships were sent into the Black Sea where they ordered the Russian fleet back to port.

The Russians became increasingly convinced that Britain and France intended to close the Straits against them. By March 1854, seemingly in a willy-nilly way, Britain and France had committed themselves to battle on the side of Turkey; landings were made in the Crimea.

Under the added threat of Austrian intervention,7 Russia, having lost almost half a million men (more by sickness than by combat), was eventually forced to evacuate European Turkey, and in 1856 (under the Treaty of Paris) to agree to the neutralization of the Black Sea. It was also forced to give up the mouth of the Danube and part of Bessarabia; its right as the protector of Christians in Turkey was rescinded. Britain, France and Austria declared that any future threat by Russia to Turkish independence would be met by them with war. The ailing Ottoman Empire was reinstated as a buffer against Russian expansion, and was admitted to the European concert of powers. Russia's humiliating defeat exposed its military and industrial weaknesses and helped to discredit the tsarist regime.

A decade later, Russia's attention was taken up by events in the Balkans. The long-term hope of the Pan-Slav movement in Russia was hegemony over the Slav states in eastern Europe. In July 1875 Orthodox Serbs in the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina - secretly armed by Russia - revolted against their Turkish masters who had ruled the area since 1463. The Turks responded fiercely. In 1876, to prevent Serbia's destruction, Russia issued an ultimatum to the Turks. Using Turkey's supposed brutal repression of Bulgarian insurrectionists as an excuse, in 1877 Russia penetrated Turkish territory as far as Adrianople (Edirne). The Turkish Army was overrun and Constantinople threatened.

The harsh peace terms imposed by Russia in 1878 caused England, Germany, France, Italy and Austria to call a second peace conference at Berlin, convened by Germany's Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. At this conference Russian terms were softened. In the new treaty the powers insisted upon the independence of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro; Austria was given the right to occupy - but not annex - Bosnia and Herzegovina; half of Bulgaria became a self-governing Turkish province named East Rumelia. To strengthen its hand further, several weeks before the congress took place in Berlin, Turkey had secretly formed a defence alliance with Britain. As a result of this alliance, Turkey ceded Cyprus - which it had taken from the Venetians in 1571 - to Britain. Russian attempts to reach the Mediterranean at Turkey's expense were again denied. Britain and France were opposed to Russia's presence either in the Balkans or the Mediterranean.

While all this was taking place, Russia had never ceased its constant march eastward. In less than a century, by the late 1630s, Russians had succeeded in crossing the whole of northern Asia and had reached the Sea of Okhotsk (Map X). They then swept southward to the banks of the Amur River, where for the next two centuries their expansion was held in check by the Manchus, who had established their rule in China in 1644. The treaty of Nerchinsk, concluded in 1689, which demarcated the Chinese-Russian border, was the first treaty between East and West. In 1707 the Kamchatka Peninsula was annexed. By 1741 Russian traders had crossed the Bering Straits to Alaska, which Catherine the Great claimed in Russia's name. Only in 1812, by which time the Russians had reached the vicinity of present-day San Francisco, did their eastern march finally come to a halt. While Russia had been outflanking the Islamic world by crossing northern Asia by land, the other European powers had bypassed the Islamic world by sea. With the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Russians withdrew from North America.

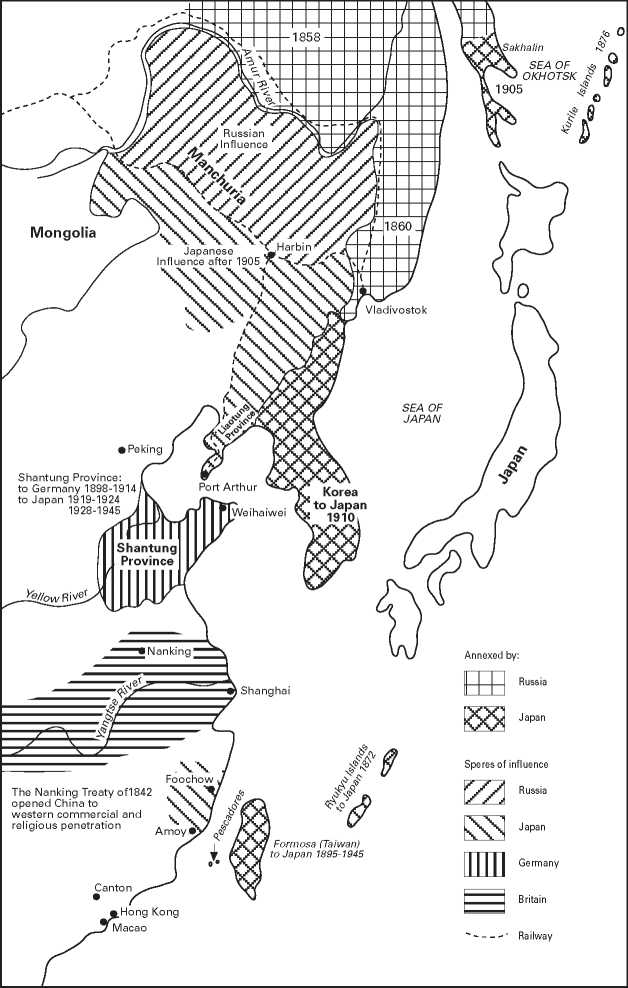

By 1914 Britain and Japan had become concerned to halt the extension of Russian power in eastern Asia. Britain had commercial interests in the Yangtze Valley, Japan had similar interests in Manchuria and Korea. The unequal treaties of Aigun (1858) and Peking (1860), forced upon China, had brought the Russian frontier to the Amur river, and to positions south of Vladivostok (founded by Russia in 1860). Under the Treaty of Aigun all the territory north of the Amur passed under Russian control. Territories which the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) had assigned to China, became Russian. China's attempts to dispute this treaty in 1859 resulted in Russia occupying parts of Manchuria. The seacoast north of Korea (territory which Russia still holds) was also annexed.

Despite the warnings of Britain and Japan, in the 1890s Russia continued to penetrate Manchuria as well as China and Korea. The Trans-Siberian Railway8 to the Pacific, which gave Russia control of northern Manchuria and made it a great power in the East, was begun in 1891 and completed in 1903. It spurred industrialization, facilitated eastern migration, and consolidated Russia's hold on eastern Siberia. Built with French money, it was also meant to woo Russia into an alliance against Germany. In 1898 Russia leased Port Arthur (Lushun) on the southern half of the Liaotung Peninsula from the Chinese. Five days later the British occupied the port of Weihaiwei (Map XI). In 1902, with insufficient strength to meet both a German threat of war in the west and Russian advances in the east, the British made a formal Naval Agreement with Japan. Japan was thus emboldened to request Russia to evacuate Manchuria - a request that was treated with contempt. In 1904 Japan struck at Russia's eastern forces without warning. In 1905 Russia was defeated by Japan on land and sea. Japan's victory signalled the beginning of the end of western hegemony in the Orient.

Russia's defeat in eastern Asia was so humiliating that it gave rise to the Russian revolution of 1905. Although the revolution failed to overthrow the tsarist regime, it provided Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (original surname Ulyanov [1870-1924]), Leon Trotsky (alias for Leib Davydovich Bronstein [1879-1940]) and other revolutionary leaders with valuable lessons and enhanced their reputation within the Communist Party. It also resulted in political concessions by the tsarist regime, the most important of which was the establishment in 1905 of the Duma (a largely ineffective parliament).

Under the subsequent Treaty of Portsmouth between Russia and Japan, Russia left southern Manchuria and returned southern Sakhalin to Japan. To the satisfaction of Britain and Japan, further Russian ambitions in the east were terminated. Yet Russia still retained control of northern Manchuria (including the Chinese Eastern Railway), parts of Mongolia, and the Chinese maritime provinces (which the Chinese alleged had been seized illegally). Henceforth, with France and Britain, Russia focused its attention on the growing threat of imperial Germany in Europe.

Halted in the east, Russian expansion had grown in central Asia. Russia's encroachment into Turkestan in the mid-nineteenth century, encouraged by military ambition and its presumed civilizing mission, had been regarded by Britain as a threat to India. Britain's response was to use Persia and Afghanistan as buffer states. By the 1860s, with Russian control of the Caucasus complete, Russia extended its influence to still wider areas of central Asia. In 1868 it took Samarkand and subdued Bukhara in Uzbekistan; in 1873 Khiva fell. Bukhara was occupied in 1874, Kokand in 1876. With the occupation of the Merv Oasis in southern Turkestan in 1884, Russia approached the frontiers of Persia and Afghanistan.

Map XI COLONIZATION OF EAST ASIA

By 1885 the Russian Trans-Caspian Railway had reached Ashkabad. From there, it was extended through Merv to Chardzhou on the Oxus in 1886. When the Russians defeated the Afghan Army at Penjdeh in March 1885, Britain prepared for war. War was avoided because the Germans sided with Russia, and also because Russia became preoccupied in Bulgaria. Only mountains now separated Russia from Persia, Afghanistan, India and China. The threat of war between Russia and Britain over Afghanistan ended in a diplomatic compromise.

Thenceforth, Russian interests were played out in Persia, which, like Afghanistan, the British regarded as a buffer state to India. In 1907, prompted by the revolution in Persia and the growing German threat in southwest Asia (the Germans had undertaken to build a railway from Berlin to Baghdad), the Russians eager to reach the Persian Gulf, secretly divided Persia with Britain. Without consulting the Persians, the British agreed to exercise tutelage over the southeast, which was chiefly desert, the Russians settled for the entire northern half of the country containing three-quarters of Persia's population. The southwestern part remained neutral. Britain, the leading sea power, retained control of the Gulf. The agreement with Russia also recognized Britain's predominant position in Afghanistan. Ignoring Persian protests, the Russian-British secret agreement on Persia was implemented when war came in 1914.

A year after this agreement, in October 1908, Russia came close to war with Austria concerning the Serbian-claimed territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Austria, the occupying power, thinking it had Russia's informal agreement, had annexed the area.9 In support of Serbia, and as mother of the Slavs, Russia called upon Austria to withdraw. Austria refused. Instead Emperor Franz Joseph (b. 1830, reigned 1848-1916) of Austria appealed to Emperor Wilhelm II (b. 1859, reigned 1888-1918, d. 1941) of Germany. France, with whom Russia had closed ranks against the Germans since the 1890s, showed little interest in becoming involved. Britain watched the growing crisis with studied unconcern. Under threat of war from Germany, Russia capitulated. The problem would re-emerge in August 1914.

If Russia's traditions appear less humane than those of other parts of Europe, it is because for a thousand years it has had to fight for the right to exist. Besieged from east, west, north and south,

Russia has had every reason to be nervous about the territorial ambitions of others. Hence, an expansive, imperial Russian state able to protect its frontiers has always been acceptable to the Russian psyche. Its historical preoccupation with security explains why the Russian state has always dominated every aspect of political, social, economic and religious life. Without a heritage of common law or of public political debate that will support the individual against the state, the state became the end, the individual the means. Security and order are what freedom and individualism have been to the West. Russia never knew Roman law, the Age of Chivalry, the Renaissance, the Reformation (with its challenge to authority), the Counter-Reformation, and the Enlightenment. Nor did it experience the challenge to political authority which the French Revolution presented to other parts of Europe. While Peter the Great introduced some western ideas, and Catherine the Great flirted with western liberalization, the oriental traits in the Russian soul (in spite of the European inheritance of the Russian Orthodox Church) have remained.

In the nineteenth century, despite palace revolts, military coups, dynastic chaos, revolutionary agitation, government corruption, conspiracy and upheaval, the exercise of absolute monarchy and absolute bureaucracy continued. Ironically, the only tsar seriously to attempt reform, Alexander II, the Tsar Liberator (b. 1818, reigned 1855-81), was assassinated. There followed the repressive rule and absolute monarchy of Alexander III (b. 1845, reigned 1881-94) and Nicholas II (b. 1868, reigned 1894-1918) the last of the Romanovs. Alas, Nicholas' claim to divine right was coupled with extraordinary incompetence. When he came to the throne, a fatal clash in Russia between the desire for modernity and absolute monarchy was a matter of time.

From the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries most Russians - overwhelmingly rural and agrarian - continued to be isolated, bound and hobbled by a rigid serfdom enforced by the state. The Russian serf knew freedom from his master only for two weeks each year. From 1593 onward even this right was revoked. After 1648 a runaway serf had no rights whatsoever; servility and conformity were enforced. All that was expected of him was that he should work and obey. Those who did not conform were regarded as a threat to society; dissidence was feared.

The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 by Tsar Alexander II did little to improve their lot. The emancipation edict, coupled with rural overpopulation (between 1861 and 1910 there was a remarkable growth in Russian numbers), exacerbated the problem of land hunger. In order to repay the cost of their emancipation, the ex-serfs were required to ransom their own persons to the state (in effect, the village), which left them in economic if not legal bondage. Land was held in common. For most serfs personal freedom and individual ownership of land remained a mirage.10

The vested interests of the aristocracy and the landowners, added to the general inertia and incompetence of the bureaucracy, ensured that nothing would be done to abate the suffering of the serfs. Genuine emancipation had to wait for the Stolypin reforms of the early 1900s. Although some relief was obtained by migration to Siberia and to the growing urban centres, rural unrest, culminating in violent uprisings, was endemic in the halfcentury after 1861.

In 1914 Russia was still a great imperial state. It had the necessary territory and numbers for such a role. Yet it lacked some of the sinews of power needed to become supreme. Eighty-five per cent of its people still worked the land. Its state-promoted industrial revolution had commenced only in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. Although state direction of industry resulted in rapid development, Russia lagged behind the more dynamic western powers and Japan. Politically, socially, industrially and economically it was ill-equipped to enter the Great War of 1914-18.

World History

World History