By 10000 BC, perhaps much earlier, humans had arrived in the area now forming Mexico. Our knowledge of Mexico’s first inhabitants is limited since few of the utensils, clothes, or buildings they produced have survived.1

The best known of these early arrivals is an individual known as Tepexpan Man, found on the northeast edge of Lake Texcoco not far from modern Mexico City. The age of the skeleton was never established since it is unclear exactly what soil stratum it came from. In any case, the remains, actually those of a woman about 5 feet 3 inches tall, are often referred to as the first Mexican, since she is likely the earliest individual we know of.

Just to the southeast of Tepexpan Man, the remains of an imperial mammoth were discovered. It was butchered in situ, and flint projectile points were found associated with it. Knife marks scar the bone where meat was cut off. We know little of the culture of Tepexpan Man and of those who killed the mammoth, since no artifacts other than the projectile points were encountered at either site. Presumably these individuals had a widely varied diet in addition to mammoth, as is typical of hunter-gatherers who hunt big game.2

For millennia the descendents of the first arrivals in Mexico survived as hunter-gatherers. They formed loose, egalitarian groups, each one probably numbering fewer than one hundred members who were united by bonds of kinship. Such groups lived in caves and temporary campsites. These highly mobile groups possessed few material goods. They were constantly migrating, skirmishing, and intermarrying with other groups. The imposition of centralized control was impossible since disaffected people could too easily vote with their feet.

From what we know of hunter-gatherer peoples, they enjoyed a comfortable margin of existence and did not have to toil endlessly to survive. A key to their survival was low population density. They also developed superior weaponry. These early hunter-gatherers used the spear thrower, or atlatl, which could launch a projectile at fifteen times the speed of a hand-held spear, giving it more than 200 times the kinetic energy.3

Between 8000 and 2000 BC, the early Mexicans turned to planting, rather merely gathering, seeds. Various plants, including squash, corn, beans, and chile peppers were domesticated. The development of agriculture allowed the formation of permanent villages by the third millennium BC. These villages were quite small, having perhaps twelve households or sixty individuals. Residence in villages allowed the development of such arts as pottery making and loom weaving. Since they were no longer constantly on the move, village dwellers could accumulate a much wider range of goods. These included milling stones (metates) to grind corn, baskets, nets, cordage, mats, and wattle-and-daub huts. This early material culture is remarkably similar to the material culture still found in many homes of those living in isolated rural areas of Mexico.4

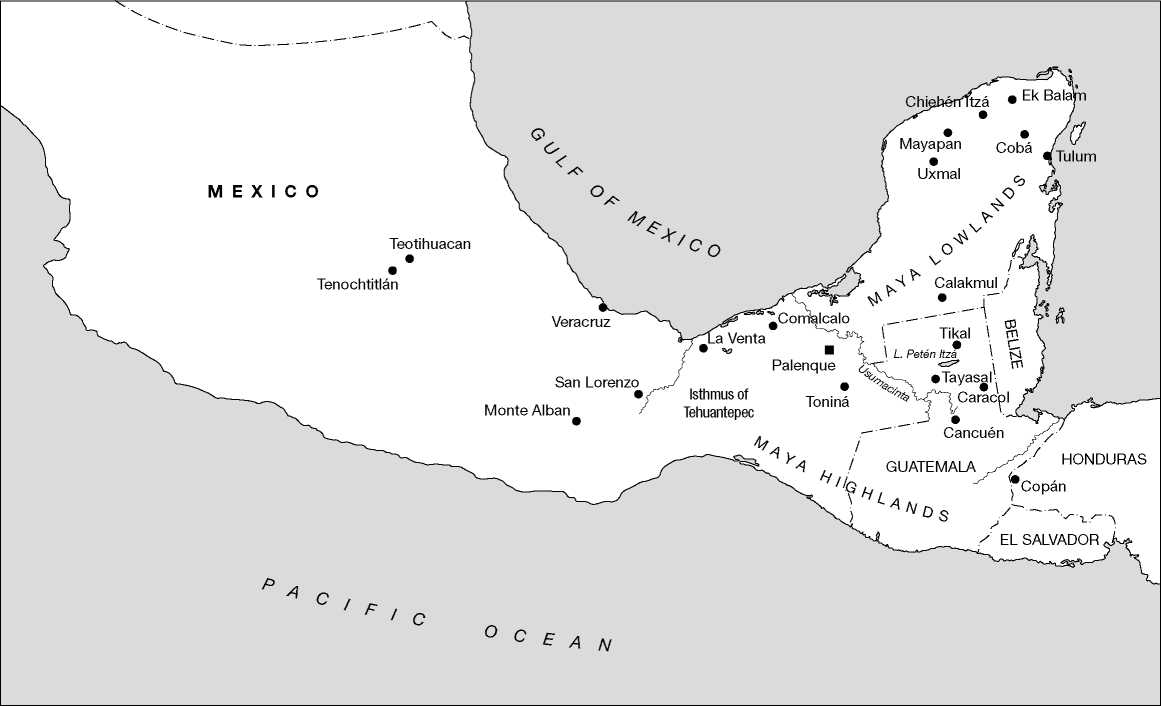

Figure 1.1 Mesoamerica

Source: Drawn by Philip Winton. From David Stuart and George Stuart (2008), Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya. London and New York: Thames & Fludson

The shift to agriculture occurred over a wide area and was a very slow evolutionary process occurring over millennia. Just as with their hunter-gatherer fore-bears, these early villages remained egalitarian for millennia. A major change produced by agriculture was increased population density.5

World History

World History