The Skalvians were one of the tribal entities to evolve out of the ancient Balts, Baltic-speaking peoples living in north-central Europe, by the ninth century c. e. Like the Nadruvians living to their south, they are thought to have been linguistically related to the Borussians, but it is possible that their dialects were closer to those of the Lithuanians, who bordered their territory on the east. The Skalvian homeland stretched inland from the Baltic Sea on both sides of the Neman River in present-day western Lithuania and the northern part of the enclave of Russian territory around Kaliningrad.

The territory of the Skalvians and that of the Nadruvians lay between lands seized by Germanic military and religious orders, the Livonian Knights of the Sword in the north and the Teutonic Knights to their south. In 1274 the united orders occupied this region. Along with other Baltic peoples of the region the Skalvians were ancestral to inhabitants of the modern nations of Lithuania and Russia (see Lithuanians: nationality; Russians: nationality).

Slavs (Slays; Slaves; Sclavi; Sklavoi; Sclaci; Slaveni; Slovani; Slovonici;

Sclaveni; Sclavini; Sclavenoi; Sclavenes; Sclavesians; Sklaveni; Sklavini; Sklavenoi; Sklavenes; Sklabenoi; Sthlaboi; Sporoi; Esklabinoi; Antes; Venedi; Vinadi; Vinades; Wends; Welatabians; Slavic peoples)

The name Slavs applies to all those European peoples speaking the Slavic language throughout history, known by a variety of names. There were many ancient tribal groups, some among whom have endured to modern times, maintaining an ethnic identity despite extensive intermingling among fellow Slavs and among other groups as well. Like the Celts and Germanics before them the Slavs spread through a vast portion of Europe.

ORIGINS

Perhaps for no other of the major peoples of Europe has the process of identifying how and

SLAVS

Location:

Central and eastern Europe

Time period:

Late fifth century C. E. to present

Ancestry:

Slavic

Language:

Slavic

When they emerged as a distinct ethnicity been more shrouded in uncertainty and controversy than for the Slavs. Slavic identity is importantly based on linguistic ties; the first Slavs emerged in part as a communication communi-

Ty all speaking the same language, a fact stressed by one of the models for the meaning of the Slavs’ name, that it derived from the word slovo, meaning “word” or “speech”—that is, that the Slovani, in contrast to their neighbors, the Germanics, whom they called Nemcy (the dumb, mute), were the people of the word or of commonly intelligible speech. (Another theory maintains that Slavic is derived from Slava for honor or glory.) But a common language is not enough to establish a common ethnic identity, especially in the ancient world in which the Slavs emerged. It was common for ancient peoples, especially those living in border regions with many ethnicities, to speak a number of tongues. In the Western Roman Empire (see Romans) most people spoke Latin in addition to their native tongue. Slavs who migrated into the Balkans during the sixth century and later probably spoke Greek as well as Slavic, and possibly the language of the Avars. Other elements than language are needed to knit a group together in an ethnic entity

Modern concepts of what is meant by an “ethnic group” have evolved as a result of archaeological and ethnographic study. The latter widened the term beyond the meaning it was given early in the 20th century as being based on types or assemblages of archaeological material, conceived of as “cultures.” The concept of “communication communities” enlarged but did not replace the archaeological culture model, because material culture is, of course, another kind of communication between people and a potent means of selfidentification, of belonging to a specific group. Additional components of what goes to create an ethnic group in current thinking include a collective name, a common myth of descent, a shared history, an association with a specific territory, and a sense of solidarity. Among tribal societies such as that of the Slavs the sense of solidarity and the myth of common descent were often provided by the tribal leaders and their dynasties, who in a sense formed the core family or clan linked (more in a mythic than an actual genealogical sense) to all the other clans in the tribe. The thrust of current thinking about ethnicity is that it is created rather than inborn, more a cultural construct than something inherited or “in the blood.”

It is obvious that none of these components can be seen directly in the archaeological record, but only, very tentatively, inferred. The realities behind what are used as “markers” for given ethnic groups—such as Early Slavic pottery or Lombard fibulae—were probably far more complex and are very uncertainly known. A piece of broken pottery tells us, by itself, absolutely nothing about its user’s language, for example. It has to be said that many scholars of the early Slavs (especially Polish and

Ukrainian ones) have seriously overinterpreted the available evidence and even indulged in wishful thinking on occasion.

This is certainly the case for claims that the origins of the Slavs can be seen in cultures of the distant past, for example, the so-called Pit Grave or Kurgan culture of the fifth millennium B. C.E. Questionable also is the claim that by about 2,000 B. C.E. the Slavs occupied the whole basin of the Vistula and most of the Oder, in addition to their eastern settlements between the Pripet Marshes and the Black Sea. Beyond the fact that the uncertainties noted in postulating the existence of an ethnic group from material remains alone are multiplied many times over when studying people so far distant in the past, it is nearly certain that the common ancestor of modern Slavic languages, which constitute such an important part of the Slavic identity, emerged thousands of years later, in the middle of the first millennium C. E. This proto-Slavic may well have emerged from precursors bearing a resemblance to modern Slavic languages, but these too must have been of relatively recent date and can have had only the most distant of relations to languages spoken by people several millennia earlier, according to the rate of language change over time known to linguists. Since the makers of the Pit Grave culture must have spoken a language (or languages) with only the remotest resemblance to proto-Slavic, it is hard to see that they or any other people of their time can be claimed as being “Slavs.” (It is not even certain that they spoke an Indo-European language.)

Such misconceptions are fueled by the assumption that people today assume and think of their own ethnicity in the same way peoples in the distant past did. Citizens of modern nation-states are assigned their ethnicity from birth and are “socialized” to think of themselves as a nationality. The process of group identification in tribal societies was far different and more fluid, particularly in the case of the mobile warrior societies that dominated central and eastern Europe after the Neolithic Age. Warriors with their families could choose to belong to a tribe or decide to leave it for another—a decision often based on the success of a tribe or group of tribes in waging war and obtaining plunder, and in providing security for lands and herds. In the tumultuous period when the historically known Slavs first appeared tribes had become less important than large multiethnic confederacies open to any warrior bands who wished to join them. Furthermore central and eastern Europe, on the edge of the great central steppe lands crossed for ages by tribes of mobile warriors and nomads from the time of the Pit Grave culture and before, were a meeting place of peoples from all over a vast region. For this reason the idea that groups there, living in periods some 4,000 years apart from one another, had any beyond the faintest of links is highly improbable.

Part of the problem in identifying the first Slavs lies in the great simplicity of their material remains. Their pottery especially is so plain and simple in shape that it provides few easily read distinguishing characteristics. The earliest claimed Slavic pottery, called the Korchak type, is actually quite similar to pottery made earlier over a wide region of central and eastern Europe, in places where there is no reason to believe Slavs lived at the time. This has made finding an original homeland of the Slavs an extremely difficult and contentious issue. Tracking the emergence and development of Slavic culture by using pottery has by necessity been an esoteric pursuit carried out by specialists. And here nationalist agendas, endemic among Slavs of different countries for centuries because of their long and troubled histories, can find a foothold. For it is all too easy for claimed affinities between different pottery assemblages found in different areas to be “in the eye of the beholder”—a scholar with the agenda to claim his country as the original homeland of the Slavs, for example, may see his pottery assemblage as more closely related to Korchak pottery than that from another country. Problems of dating also have plagued archaeological studies of Slavic material.

The archaeological remains of the earliest Slavs have been identified by excavating areas where the earliest of written sources place them—along the Danube in the sixth century C. E. and somewhat later in the Balkans. There is linguistic evidence that early Slavs may have lived in Moravia (modern Slovakia) and Bohemia (the modern Czech Republic), Ukraine, and other areas, and these places have been excavated as well. The material found in all of these regions shows enough similarity to assume, tentatively, that the Slavs at this time had “crystallized” into a group with a consciously shared ethnicity based on language, a common material culture, and possibly a shared ideology and religion. Before this period the existence of a distinctively Slavic ethnic group becomes a matter of increasingly tentative speculation.

The crystallization of Slavic identity may have taken place in the context of the conquest of the GOTHS, a German-led multiethnic confederacy north of the Lower Danube and the Black

Sea, and by the HUNS, a Turkic steppe people, in the fifth century. It is thought that part of the process of forging a Slavic identity involved the Huns. The latter’s disruption of the previous Gothic power structure may have opened opportunities for the first Slavs; some among them very probably joined the Hunnic forces, learning from them how to fight on horseback and thus becoming formidable and mobile warriors. Slavs may first have entered the Middle Danube region to the west, where they later lived, as part of the Hunnic hordes. The Huns’ example may have served the Slavs well as they began in the sixth century to spread quickly over a wide area of eastern and central Europe into most of the countries where Slavic peoples live today

This expansion was probably not a wholesale migration, because there is little evidence of depopulation in the areas inhabited by the earliest Slavs, nor of a reason why large groups would travel to lands far distant to settle. More likely, small bands of young Slavic warriors made such journeys into lands formerly held by Germanic elites, such as the Vandals and Lombards, who had departed to take advantage of the crumbling of Roman power in the south and west. These Slavic warriors may have been followed by small farming groups who were taking advantage of lands vacated by migrating Germanics and others.

LANGUAGE

All modern Slavic languages are thought to have diverged from a common language no longer in existence (and thus called protoSlavic). Features of this hypothetical language have been reconstructed by comparing modern Slavic languages, but attempts through linguistic study to discover where and when protoSlavic was first spoken have not yielded a theoretical consensus. Various places of origin proposed center on the general area between the Danube delta and the Pripet Swamp and from the oder River in the west to the Dniester in the east. The fact that the different modern Slavic languages, even those geographically distant from one another, are similar enough that their speakers today can roughly understand one another strongly suggests that they diverged from proto-Slavic in the recent past, probably not long after the earliest evidence for the emergence of Slavic ethnicity around the late fifth and early sixth centuries C. E., when archaeological evidence of these early Slavs appears in the different regions of Slavdom.

There are three basic groups of Slavic languages. East Slavic languages are Ukrainian and Belarusian, and Russian. South Slavic languages include Bulgarian, Serbo-Croatian (with separate Serbian and Croatian dialects), Macedonian, and Slovenian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin, also of the Serbo-Croatian group, have recently been cited by their national groups to be separate languages. West Slavic languages include Polish, Kashubian, Sorbian, Czech, and Slovak. Old Church Slavic (Slavonic) is an archaic form of the South Slavic language that was spoken in Bulgaria and Moravia; it was adopted in Bulgaria for use in Christian liturgy in the ninth century and is still used in the ritual of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Polabian is a Slavic language, now extinct, that was spoken in the region around the Elbe River east to the Oder. It is probable that there were other Slavic tongues, which have disappeared, especially in the isolated valleys of the Balkans.

HISTORY

First Phase of Expansion:

The Problem of a Slavic Homeland

Problems of dating the earliest Slavic archaeological finds have made it extremely difficult to identify a single homeland from which the Slavs expanded into the territories where they later dominated. Slavic material dating from the sixth century has been found, as noted, in Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and elsewhere.

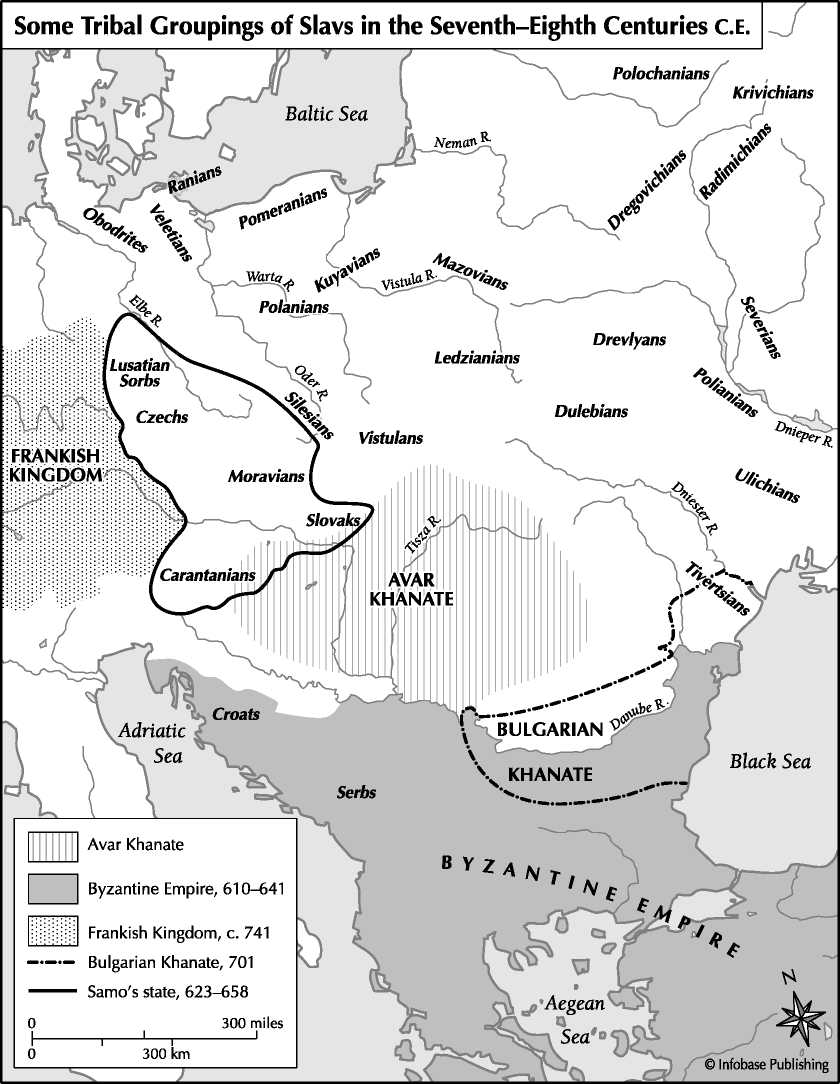

By using early manifestations of pottery of the Slavic Korchak culture, named for a region in Ukraine where it was first identified, and of the small, sunken-floored dwellings that are typical of Slavs, four important movements of early Slavs have been identified: first, along the east flank of the Carpathian Mountains toward the Danube plain and the Balkans; second, along the north flank of the western Carpathians through southern Poland; third, along the southern flank of the western Carpathians toward the Middle Danube and the Elbe; and fourth, eastward in Ukraine. These movements, perhaps emanating from two separate centers, one in Ukraine and the other along the Danube, or possibly all from Ukraine, are too little understood to resolve fully the question of the original Slavic homeland.

Danube Plain and the Balkans The appearance of Korchak pottery of the late fifth and early sixth centuries near the Lower Danube and the Balkans may have resulted from the crystallization there of a Slavic cultural identity possibly by a process such as that outlined previously. It could also have been carried there by peoples who were taking advantage of the depopulation of this region north and south of the northern Roman imperial frontier. If this happened, the most natural route would have been from the western Ukraine along the arc of a forest steppe beside the eastern and southern Carpathians, through Moldova and Romania, open country making for ease of movement. This scenario would furnish a strong argument for Ukraine as the homeland of the Slavs, because the other known Slavic movements consist of an expansion from the Lower Danube upriver, an expansion into Poland that could have originated in either the Danube region or Ukraine, and an expansion from the western Ukraine eastward. On the other hand, if the dating of Slavic sites along the Danube to the late fifth century is correct, they would predate Ukrainian Korchak pottery by more than half a century.

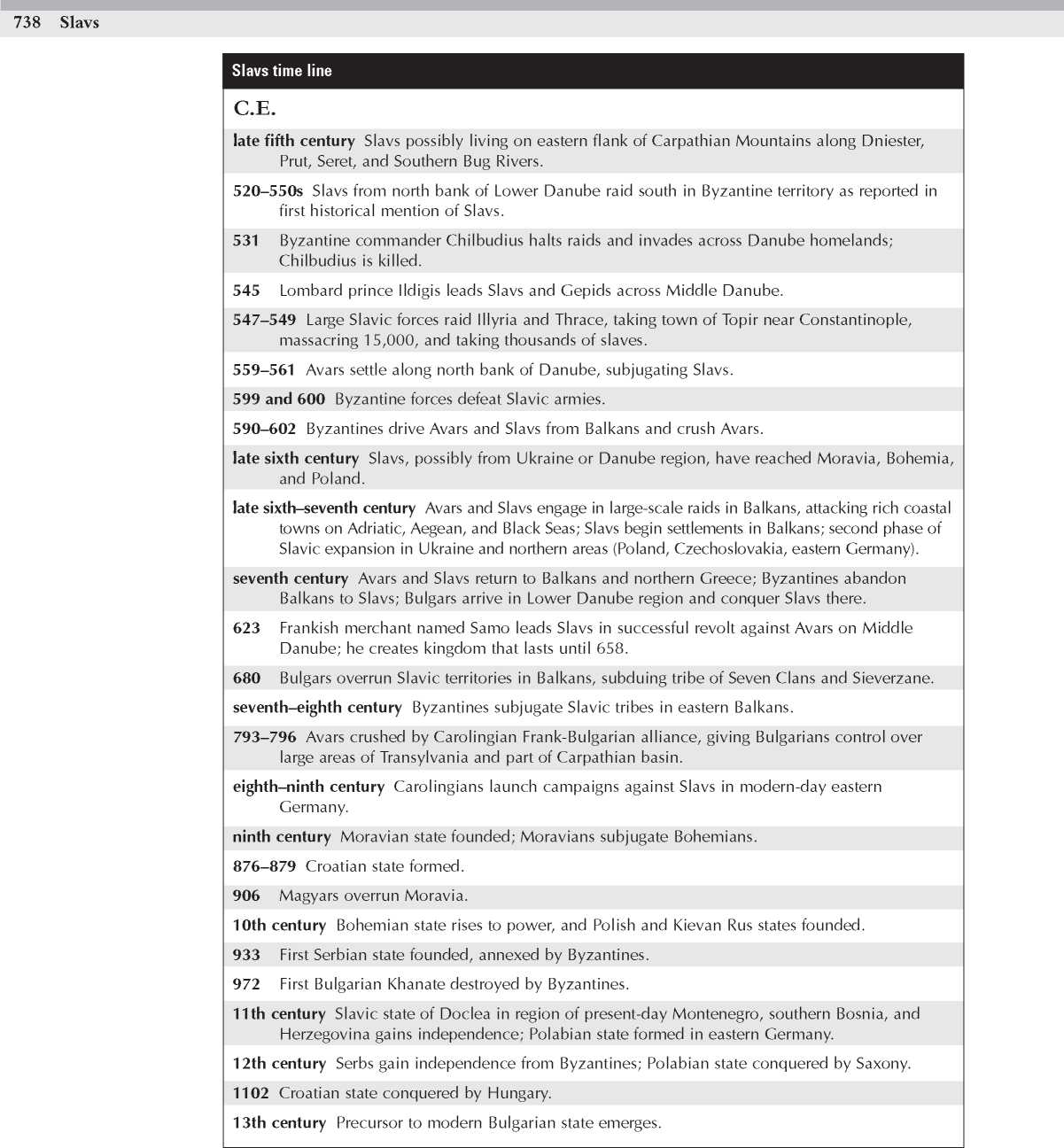

It is the Slavs along the Danube border with the Roman Empire who first appear in records written by the Byzantines of the Eastern Roman Empire, referring to raids by a people they called Sclaveni, who were also joined by another group called Antes. The sixth-century Roman writer Procopius says that the Antes were once a single people called Sporoi, a word that is close to a proto-Slavic word meaning “multitude.” He describes their raiding in the 550s, which they had begun in the 520s. Thus the Slavs who had arrived in the previous century may have been peasant communities rather than war bands, and indeed this accords with the character of their material culture. Several Germanic groups, probably including the Lombards, Gepids, and Heruli, remained in the area at this time. The Slavs settled away from these groups but met and mingled with the complex mix of other peoples in the area, natives of the region, people attracted by the lucrative Roman trade, and others introduced there as part of the multiethnic confederacies that had long impinged on this area so close to the Roman border. When the Slavs later began to raid Roman territory, it is thought that they probably took enough slaves with them back over the Danube to make a significant contribution to the population there. These and all but the Germanic groups soon adopted the Slavic Korchak pottery and house types, indicating that the Slavs were the most dominant non-Germanic group in the region.

Along the North Flank of the Carpathians into Poland

A variant of Korchak-type pottery is thought to represent the Slavs who moved along the Carpathians into Poland. When it was first made is unclear, but its later phase has been dated to the turn of the sixth and seventh centuries. Dates have been claimed for earlier such pottery found in Moravia as early as the late fifth century, but the most reliable dating is for the middle or later sixth century. Procopius, describing the migration of the Germanic Heruli north to Scandinavia in 512, writes that they passed through territory of the Sclaveni, but his account is ambiguous as to where this was. The Olsztyn culture (named for a region in northern Poland) shows substantial signs of change that began just before the middle of the sixth century and lasted for about a hundred years, its cemeteries containing what appear to be Slavic fibulae from the Lower Danube delta, and at least one site containing possibly Slavic pottery. The Olsztyn culture from this period seems to be a mixed one, with both Germanic and Slavic elements. The change in this culture may document the arrival of the Slavs, but whether from the Danube region, where the earliest historical accounts document the presence of Slavs, or from the western Ukraine, which is closer to Poland, is uncertain (although the Danubian Slavic fibulae suggest that they originated there).

Most signs of Germanic culture had disappeared from Poland by the early sixth century, but BALTS continued to live in the northeast.

Korchak pottery first appears at its type site in Ukraine around the middle of the sixth century. By the end of the century Korchak pottery makers seem to have expanded over large areas of the western Ukraine to the Dnieper in the east. Villages were built on terraces just above river floodplains, consisting of five to 10 huts. These were built in the Slavic style—of timber, square with sunken floors and a stone-built oven in one corner. Their dead were buried in small cremation cemeteries, some in urns and some not. On the basis of a text by Jordanes, a sixth-century historian of the Goths, some Russian scholars believe these to have been the Antes, whom Jordanes places from the Dniester to the Dneiper, but also near the Black Sea, a region that is steppe land different from the forest steppe and deciduous forest regions to the north where the makers of Korchak pottery lived. This region was probably a route frequented by warlike steppe nomads, therefore a dangerous area for settlers. Jordanes’s account of the Slavs is considered suspect because of his uncertain geography, which in some instances is nonsensical.

The timing of this initial phase of Slavic expansion is highly uncertain; it could have taken as little as 50 years or more than twice as long. In either case the expansion was remarkably rapid, whether accomplished by a large movement of people or by influences exerted by Slavic warriors on the natives in the new lands. Written sources suggest that the latter was accomplished, at least in part, by the Slavs’ practice of allowing prisoners taken in war to join their ranks and become Slavs. However it was achieved, by about the middle of the sixth century Slavic culture was established in an area several thousand kilometers in extent, with a population density estimated at several people per square kilometer.

Procopius writes that the Antes began raiding Byzantine territory in the reign of Justin I (518-527), when they were decisively defeated. When Justinian I ascended to power in 527 he turned much of his attention to regaining the territory of the Western Roman Empire. The Slavs’ many raids in the 530s may have benefited from undermanning of the empire’s frontier along the Danube as a result of Justinian’s campaigns in the west. Procopius mentions that the Slavs and Antes were joined in these raids by Huns. In 531 the commander Chilbudius halted the raids and carried the war into the raiders’ homelands, so that the Slavs and Antes assembled in massed armies. A large Sclaveni army met Chilbudius, who was killed in the melee.

The Sclaveni and Antes were not firm allies and sometimes even fought one another. The Byzantines probably exploited this friction to divide and conquer the raiders by enlisting the Antes asfoederati (federates), or allies. This possibility is suggested by the fact that in the middle of the sixth century after their war with the Sclaveni had been resolved Justinian offered the Antes an abandoned fort and surrounding lands on the northern bank of the Danube, and a large sum of money to protect that part of the frontier, ostensibly against the Huns, but possibly against their brother Slavs, the Sclaveni. The Antes accepted the offer; 300 of them even joined in a war against the OSTROGOTHS, formerly part of the Gothic confederacy that had taken Italy.

Justinian took steps to strengthen the Danube border against the Slavs, restoring many forts and building new ones; he also seems to have brought all trade across the border to a halt, judging by the lack of coins of his reign in the territories beyond the Danube. The large imperial armies were unsuccessful against the small mobile war bands of the Slavs, and the Byzantines’ countermeasures only encouraged the Slavs to become more organized.

In about 545 the Lombard prince Ildigis led a group of Slav and Gepid warriors across the Middle Danube possibly from southwest Slovakia or northeastern Austria. Procopius describes a Slavic army as large as 3,000 men raiding Illyria in 547-548; a Byzantine army of 15,000 in the area failed to engage with them, for unknown reasons. The Slavs raided Illyria again the next year and moved into Thrace as well. Their incursions placed them close to Byzantium itself when they took the fortified town of Topir nearby. Procopius writes that they massacred most of the men, some 15,000, leaving the area covered with unburied corpses, and took all women and children into slavery. According to Procopius their methods of killing were brutal (at least by modern standards, perhaps less so by theirs), including impaling the enemy through the anus on sharp stakes, beating them, and burning them alive. There seems little reason to doubt that Procopius’s account had at least some grounding in fact. The fruits of these raids for the Slavs included huge numbers of slaves, cattle, and sheep—too many of the latter to take away with them so that some were shut up in huts with their masters and burned to death. Numbers of the slaves taken north across the Danube were later ransomed and allowed to return home; some of these chose to stay and were accepted into Slavic society.

The Slavs were not always successful, and a raiding party on Thessalonica on the Greek Peninsula in 550 called off their attempt when they heard of the proximity of an imperial army led by Germanus. The Byzantines are known to have defeated Slavic forces in 599 and 600, according to letters of congratulation from Pope Gregory I.

There was an apparent cessation in raiding from the 550s to the 570s; then at least in part under the influence of the Avars, nomads out of Mongolia, raiding began again, now deep into the Balkans. The Avars had arrived and settled on the north bank of the Danube in 559-561, absorbing the Slavs as subject allies into their probably multiethnic confederacy made up of peoples the Avars had swept into their train as they moved across central Eurasia. They stopped for a time on the Pontic steppe, before continuing westward. Slavs from the east probably also accompanied the Avars.

The Byzantines again attempted their divide-and-conquer tactic, paying the Avars large amounts of gold to fight the Slavs and to desist from attacking Byzantium; the Avars were allowed to settle in Pannonia. Accordingly the Avars attacked Slavs living along the Lower Danube and an intense struggle ensued. Meanwhile in 578 after Avar forces were ferried across the Danube they began making incursions onto Byzantine lands ostensibly for the purpose of furthering their war against the Slavs. These led to a series of raids deep into Byzantine Greece, attacking rich coastal towns on the Adriatic, Aegean, and Black Seas. Slavs later followed in the wake of the Avar raids, which made their penetration easier, raiding in their turn and then settling lands depopulated by war and by an outbreak of bubonic plague that had decimated the population in the 540s. In addition Justinian’s legislation and fortification program seems to have destroyed the peasant economy of the Balkans. By the early seventh century the Avars had established a powerful hegemony in central Europe, from the eastern Carpathians to the eastern Alps. The Slavs participated in this by way of tribute and service provided to their Avar overlords, but some of them also in time became members of the Avar warrior elite. In this their earlier experience with the Huns may have helped them; at least some among the Slavs probably became masters of steppe-style warfare.

In all probability it was at first as part of the Avar order that the Slavs eventually spread their culture throughout the Balkans. From the end of the sixth century to the middle of the seventh a large-scale Slavic settlement of the Balkans occurred. These Slavs made no attempt to use abandoned Roman forts, suggesting that they were peasant farmers rather than warriors. But even while this peaceful migration occurred, Slavic warriors continued to conduct destructive raids on Byzantine cities at will, taking plunder.

It is unclear to what extent Slavs settled in Greece in these centuries; there is little archaeological evidence of them there at this time or in the southern Balkans. Few of the typical Slavic sunken-floored huts, pottery types, and burials have been found. Written sources claim that Slavs displaced Greeks in the western Peloponnese, sending them fleeing to Sicily; the region around Thessalonica became known as Macedonian Sclavinia. There is strong linguistic evidence for their presence at least by the seventh century in the number of Slavic place-names in the southern Balkans. It may be that at this time Slavs in Greece and the southern Balkans had abandoned their simple material culture, a strong likelihood if the accounts of their becoming rich through raiding are true.

The former province of Dalmatia (in modern Croatia), where Slavs began raiding in about 550, had been the last surviving Western Roman province and was currently part of the Eastern Empire. By the time of the arrival of the Slavs a significant number of the Romanized but multiethnic population had remained there. Over time as rapprochement between the Slavs and the Dalmatians took place the latter’s culture had a strong effect on the Slavs, perhaps greater than in any other Slavic territory, and was important in the development of Moravian culture. Slavs and Avars increasingly penetrated this area after the fall of Sirmium gave them access to the western Balkans, from the 570s to the 590s destroying towns and settlements all the way to the coast.

The Byzantines concluded a peace treaty in 590 with their great enemy, the Persians, which allowed them to divert a large part of their military resources from the east to their northern border. There they began a full-scale war on the Sclaveni and Avars, aided by their allies, the Antes, who had been attacking Sclavene settlements since the 580s. The Byzantines mounted a massive invasion across the Danube, defeating the Avars and killing the Avar khan’s four sons along with possibly as many as 30,000 Avar warriors. After the emperor Maurice Tiberius was assassinated in 602 in a military revolt provoked by the hardships of the war against the Avars, under his weak successor Phocas internal strife prevented the Byzantines from maintaining pressure on the Avars. They in turn recovered and attacked the Antes, who may have been destroyed or driven them from the region, for they are never mentioned in written sources again.

Byzantine disorder allowed the Avars and Slavs again to raid deep into the Balkans and Greece, concentrating on Dalmatia. In the period from 612 to 614 Slavs attacked Salona, the capital of Dalmatia, and its populace sought shelter inside Diocletian’s walled palace at Split. They then turned to Thessalonica on the east coast, using siege machines, an indication of the increasing sophistication of the Avar and Slav fighting forces. The chronicler Isidore of Seville in Visigothic Spain writes that in the fifth year of the rule of the emperor Heraclius (615) the “Slavs took Greece from the Romans.” During this period Slavs settled in abandoned countryside in the Balkans, where there is evidence of extensive soil erosion at this time (the thick deposition of soil in rivers that occurred is called the Younger Fill), which could have been caused by overgrazing or climate change and probably contributed to the collapse of the Byzantine economy in the 650s, when use of coins was abandoned for barter.

The weakening of the Byzantine military through lack of funds caused Heraclius to roll back the northern frontier and withdraw all troops from the Balkans, making a virtue of necessity and opening up the area to Slavic settlement, which continued to be sparse, in part because of the degradation of farmlands through the great erosion event of the Younger Fill.

Slavs were part of the siege of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) by combined Avar and Persian forces in 626, serving mainly as infantry but also manning dugout boats to ferry Persians across the Bosporus to the western side. The Byzantines were able to sink many of these and many Slavs drowned; this reverse caused most of the Slavs to leave the battle, which turned into a disaster for the Avars and Persians. The defeat and the Slavic loss of life seem to have caused a crisis of confidence among Slavs concerning the Avars, whose influence on the Slavs declined for several decades.

Slavic settlement of the Balkans continued throughout the seventh century, in Macedonia; near Thessalonica, Dalmatia, northern Thrace; and elsewhere until large areas were in Slavic hands. Local groups began to organize into tribes during this period, as their settlements stabilized. The former province of Lower Moesia along the Danube, which was probably one of the earliest areas settled, became known to the Byzantines as Sclavenia. Tribes here known from Byzantine sources include one called the Seven Clans; another was called the Sieverzane. A large number of tribes emerged in Macedonia in the region of Thessalonica (which remained in Byzantine hands). The mountainous interior of the Balkans seems to have been avoided by Slavic settlers—as few tribal names here are known. Only a few clearly Slavic archaeological sites in the Balkans in general have been found from this period, but several of those found were fairly large, comprising as many as 60 and more than 100 of the typical Slavic huts; these settlements had no defensive walls. They were not towns, however, and Byzantine towns and forts were mostly abandoned. Excavation of these has yielded coin and silverware hoards and destruction layers dating to the time of the Slavic raids.

Contrary to Isidore’s comment, important areas of Greece remained in Byzantine hands, particularly coastal areas near ports, as well as areas of the southeastern Balkans. Athens and the surrounding regions of Attica and Boeotia were still controlled by Greeks, and Athens remained a cultural center where scholarship and education thrived. The Byzantine theme (administrative region) of Hellas, which included Athens and surroundings, was established by the end of the seventh century The region of Thrace surrounding Constantinople also continued under Byzantine control.

Gradually the Byzantines imposed their control on Slavs in the eastern Balkans, partly driven by the impoverished empire’s need for revenue. Tribes here were subjugated by the emperors Constans II in 656-657 and Justinian II, who consolidated control in campaigns in 688-695 and 705-711. A Thracian theme was created in 680-687, and Slavs there were obliged to pay tribute and supply military aid, including grain. Slavs in Macedonia and Greece were more resistant against expeditions sent against them in 656 and 686. Numerous Slavs were taken prisoner in these campaigns; some of these were recruited into the Byzantine army; others were resettled in Bithynia in Asia Minor. The subjugated Slavs revolted repeatedly. In areas where Slavic tribes remained independent, some developed new, more organized political institutions, probably to mount more effective resistance to any Byzantine attempts to subjugate them. As in the case of Germanic tribes near the Roman borders in the first centuries C. E. Slavs soon became influenced by Byzantine civilization and its governmental and military system, whether they were part of the empire or not.

In the western Balkans Slavs expanded up the valleys of the Drava, Sava, and Mura Rivers into the flanks of the eastern Alps and had settled large areas of Dalmatia, including coastal regions and islands, by 642. Slavs ransomed prisoners and religious relics to Pope John IV around this time. As elsewhere archaeological remains of the Slavs from the seventh century here are sparse. Those in the eastern Alps apparently joined with indigenous populations, including Germanics, to develop the Carinthian culture of the seventh and eighth centuries, which has Germanic elements as well as elements rooted in the culture of late antiquity (see Carantanians).

According to a mid-10th-century account by a Byzantine writer, Constantine Porphyro-genitus (the emperor Constantine VII), one of whose informants lived in Dalmatia, Croats and Serbs settled in the eastern Alps in the reign of Heraclius in the first half of the seventh century. This would antedate any known Slavic archaeological remains in the Balkans; yet, given the scarcity of any signs at all of the Slavs there in this century, this early settlement by Croats and Serbs is not impossible. Yet some of the material in this text has features that make it appear more a legend than a straightforward account, with elements characteristic of Slavic folktales, and there are duplications suggesting that it was simply a compilation of earlier material—different versions of the same story, as in many medieval annals and histories, which often are collections of oral traditions—with no attempt at verification. Along with factual errors and other problems, this makes it difficult to assess how far Porphyrogenitus’s account can be trusted.

Slavic Expansion beyond the Balkans

In the latter sixth and seventh centuries Slavic societies elsewhere continued to expand their territory and to consolidate settlement in lands already occupied; their social organization also stabilized. Some archaeologists identify a “second wave” of Slavic migration to the area north of the Danube, possibly from Ukraine, in the middle of the sixth century; these settlements have much less material from other cultures and are more “purely” Slavic. The new territories elsewhere were mostly located in the forest zone of central and eastern Europe, marking a break in the former Slavic concentration on forest steppe lands. In spite of the new ecology the Slavs confronted, which probably necessitated new methods of subsistence, Slavic material culture remained remarkably uniform over its whole extent.

A puzzle in this uniformity is the question of why the huge quantities of plunder that the Danubian Slavs took in the raids on Byzantine territory seem to have made so little impression on Slavic culture until the mid-seventh century Where did all of the gold and silver go? Where are the great stores of weapons taken from Byzantine cities? Why indeed are iron weapons not found in Korchak sites? And again, if theirs was a deliberately simple culture in terms of material goods as some scholars have suggested, why did they raid at all? Even though only the Danubian Slavs took part in raids, it would seem likely that given that people over a wide area seem to have become part of a pan-Slavic culture, some of this loot would circulate through the Slavic lands, to Ukraine, Poland, and elsewhere. This is one of the many mysteries that shroud early Slavic history, which may in time be elucidated with more archaeological finds and the secure dating provided by the recently developed science of dendrochronology (tree-ring dating).

Slavic sites found in the Middle Danube in southwestern Slovakia and northeastern Austria may date from the mid-sixth century, because an incursion by Slavs and Gepids into

Byzantine territory noted by Procopius, which took place in about 545, seems to have originated here.

In Ukraine the second wave of Slavic expansion involved the Penkova culture, named for a site near the village of Penkova. Penkova sites occur in a zone distinct from that of the Korchak culture, located to the southeast over a wide area from the edge of the Pripet Marshes across the Dnieper into eastern Ukraine. Some Penkova huts had hearths freestanding rather than in one corner, and the pottery is more varied in form and sometimes decorated with pinched rims to give a frilled effect. The general impression given by Penkova pottery—to the nonspecialist, however—is that it is nearly identical to Korchak pottery. Abandoned iron tools have been found in Penkova contexts, in contrast to Korchak sites, and some decorative metalwork.

Further expansion in Poland beyond the rich farmlands in the southeast during this time was limited, mostly following the major river valleys, and the culture remained largely unchanged here. Material from the latter sixth century in southern Slovakia, Moravia, and Bohemia is very similar to that from contemporary Poland to the north, and the Czech and Slovak languages in their early stages were similar to South Slavic languages, making the origin of the Slavic groups here uncertain. Material in Bohemia has been called the Prague Culture, although it is very similar to that found in Ukraine and elsewhere.

Prague-type pottery from the latter seventh century (dated by dendrochronology to the 660s) is found in former Germanic areas near the Elbe, Saale, and Havel Rivers, in the later territory of a tribe called the SORBS (whose language has survived to the present). Slavs here moved into areas formerly settled by Germanic peoples that were reverting to forest. In the northern part, north of Brandenburg in Mecklenburg and Pomerania, where until the 19th century a now extinct Slavic language called Polabian was spoken, a distinct culture, named for the town of Sukow in Mecklenburg and Dziedzice in Pomerania, has been identified. The Sukow-Dziedzice culture differed from that of most Slavs in having ground-level rather than sunken-floored dwellings and almost no cemeteries, and their pottery is more varied. The Sukow-Dziedzice culture also occurs over much of northwestern and western Poland. This distinct tradition may have resulted from assimilation of native Germanic peoples with incoming Slavs.

Arrival of the Bulgars in the Danube Region

In the seventh century the Slavs in the Danube frontier region were under the control of the BULGARS, a Turkic-speaking people who had emerged as a power in the steppe region near the Sea of Azov; their coalition may have included Hunnic remnants, Avars, and possibly ALANS. The breakup of a powerful confederacy of Bulgars on the Don and Caucasus steppe (sometimes called the Khanate of Great Bulgaria) caused one group of Bulgar horsemen to ride westward, they reached the eastern fringes of Avar territory on the north bank of the Danube, where they established hegemony over the Slavs.

These Danubian Bulgars, led by Khan Asparukh, began attacking the Byzantine frontier and imperial territory in Thrace. In 680 they overran the former Lower Moesia, now the largely Slav-settled “Sclavenia,” subduing the Seven Clans and the Sieverzane. Emperor Constantine IV (Pogonatus) could do no more than cede the Bulgars this territory, although the Bulgars agreed to pay tribute.

A third phase of Slavic expansion was marked by relative stability in Slavic territories, and by a slow development away from the simple egalitarianism of the past, as Slavs began to accept non-Slavic influences, especially from the Byzantines, the Lombards in Italy, and the Avars. The pace of this change increased greatly in the mid-seventh century, as new pottery types developed, made more regular in form apparently through the use of a kind of turntable (not a potter’s wheel), and the use of mounds to cover burials was adopted.

Developments North of the Carpathians

In the Polish region north of the Carpathians significant changes in material culture, from the mid-seventh century, seem to signal a departure from the simple Slavic culture of the past. In southern Poland more accomplished pottery was made, finished on what is called a “slow wheel” that allowed for a more regular shape. Pottery was decorated and made in a greater variety of shapes; influences from south of the Carpathians are apparent. Dwellings continued to be of the familiar sunken-floor type, but burials of cremated remains now were commonly covered with earthen barrows and placed in small cemeteries, possibly for clan or family members. Such burials, memorials to the dead that would have been visible in the landscape, may signal a deeper connection with place than the mobile Slavs had ever had. In eastern Poland hilltop strongholds (albeit with relatively weak defenses) were first built in the early seventh century. Rich ornamental metalwork has been found in these strongholds, showing mixed influences of Byzantine, Lombard, and Avar cultures.

The impetus for some of these changes seems to have been the Avar khanate, where pottery similar to the southern Polish type was made. The change to barrow burial started south of the Carpathians, moving first to Moravia and Bohemia and then northward, but because Avars themselves did not make barrow graves, this change was not a matter of direct influence. It may be that the raising of barrows commemorating the dead was of a piece with the Slavs’ new interest in a more elaborate material culture. Personal ornaments and barrows may signal the rise of a sense of pride and individualism among elites, similar to that of the Germanic elites. The style of Slavic metalwork at this time shows influences from the late Cherniakhovo culture, the Ostrogoths in Italy, and the Gepids in the Carpathian basin. A type of fibula particular to the Slavs (called the Slavic fibula) was made in a considerable variety of forms, thought to have symbolic significance and to announce group affinities. Slavic fibulae are found from the Mazurian Lake district in northeastern Poland to the lower Danube and Crimea, in Southern Slavic areas, in Penkova lands in eastern Ukraine, but rarely in the former Korchak territories on the west bank of the Dnieper, where a distinct style of fibula developed, or in Western Slavic areas. Fibulae in parts of the Balkans derived their form from Late Roman models.

Another common ornament whose variants seem to show relationships between groups in different regions was the temple ring; numbers of these were worn by women attached to a leather headband (hence the name temple). Similarities in temple rings from the Danubian area and Penkova lands may suggest cultural links between these two areas. By the eighth century temple rings here were being influenced by Byzantine fashions. Temple rings are found in Western Slavic areas sporadically in the seventh century and more commonly in the eighth.

Avar Influences in the Seventh Century

A zone between the Danube and the southern Carpathians east of Bohemia has cemeteries where both Avars and Slavs were buried. Some of these are large; one near Bratislava has a thousand graves. Most of these were inhumations. Some burials had grave goods, either Avar or

Slav; a typical artifact of the latter were S-shaped temple rings. Pottery was decorated by incising the wet clay with a comb-shaped implement to make parallel lines, either straight or in “squig-gles,” or by stamping. Some pots were wheel-thrown. In general Slavs here had reached a higher state of development, under Avar influence, than had their brethren elsewhere. The wide-ranging Avar society combined traits from Byzantine and Frankish Merovingian cultures.

This Slavo-Avar culture is found in present-day Slovakia and Hungary, where large cemeteries attest to the stability of settlements. There is major disagreement between Hungarian and Slovakian researchers as to the ethnic affinities of the deceased in these cemeteries. Although there are graves with clearly Slavic material and others with Avar artifacts—one of the markers of difference is the presence or absence of the Avar stirrup—Slovakian scholars claim that some of the apparently Avar graves are of Slavs who had adopted Avar dress and equipment, whereas Hungarians believe them to be foreign nomads. Skeletally Mongol or Asian features are claimed for some of the bodies, possibly evidence of a new wave of steppe nomads. Artifacts of late Avar type from the eighth century found in these cemeteries could have been introduced in this migration, although they could also have been the products of a local development. In any case the material culture here was rich by Slavic standards; there are even glass vessels, probably imported from Francia.

Avar-style belt mounts are found in many male Slavic graves south of the Carpathians, the material expression of elite status and allegiance to the Avar power bloc.

The importance of Frankish influence south of the Carpathians is shown by the activities of a Frankish merchant named Samo, who in 623 according to a Frankish account written in the 660s led Slavs living somewhere on the Frankish borders in a successful revolt against the Avars. Fredegar, the writer of the account, says that Samo became rex (king) of his Slavic followers, adopting Slavic customs (including the taking of 12 wives). Samo’s polity is unlikely to have been worthy of being called a state in any medieval or early-modern sense of the term, for when he died it vanished without a trace. The most notable event of Samo’s reign was a victory over forces sent against him by the Frankish king Dagobert in 631. There has been considerable controversy over the location of Samo’s kingdom; no archaeological trace of such a political organization has been found. It may have been in the region of Vienna on the fringes of the Slav-Avar territory, far enough away from Francia to have stretched Dagobert’s military to its limits; if it was, that could explain how the Slavs were able to prevail over the most powerful and successful of Merovingian kings since Clovis. Wishful thinking and national pride of some archaeologists have led to claims, without concrete evidence, that Samo’s kingdom was located in the Morava River valley (in the present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia) or present-day Slovenia; this is unlikely because these areas were not under Avar control. Samo’s reign lasted until 658.

There is not enough evidence to assess how Slavic culture may have developed in present-day Ukraine in the seventh century An important development that would affect the Slavs later was the rise in power of the Khazars, an ancient Turkic people who had emerged in the Transcaucasus in the second century C. E. By 650 they dominated the steppes from north of the Caspian Sea, over much of Caucasia, and north of the Black Sea between the Dniester and Don Rivers. They absorbed the Bulgars who had remained in the steppe lands and the Alans. Their influence on peoples living in the forest zone north of the steppes crystallized the ethnic identity of the Magyars, who would later invade and take control of the region of present-day Hungary.

Separation of Early Slavic Unity into Regional Zones

During the eighth and ninth centuries three major and discrete Slavic traditions that paved the way for the development of the medieval Slavic states emerged. In the region north of the Carpathians people in Poland and Slavic regions to the west became part of the Western Slavic zone. East of Poland Slavs living in modern Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine made up the Eastern Slavic zone; south of the Carpathians Slavs from the head of the Adriatic, through the Balkans and northern Greece to the western Black Sea coast, became part of the Southern Slavic group. Major revisions in dating of the Slavic material that documents these new traditions, some of it as much as 200 years later in date than had been thought (now believed to be eighth century rather than sixth), have led to a telescoping of developments, and to the realization that this division happened much more swiftly and dramatically than had been thought.

There is evidence that at least in Western and Eastern Slavic regions the eighth and ninth centuries saw an increase in Slavic populations. In Poland detailed field-walking surveys to locate and measure the size of archaeological sites have documented that by the end of the ninth century settlements and dwellings had increased to a number that could have supported a population three times that of the sixth century Larger populations were probably among the factors that led to a more complex and organized society.

Slavic societies had closer relations with more advanced neighboring cultures in this period; to a great degree (although not entirely) these took the form of what is called a coreperiphery relationship, with most influence moving from the more developed core outward, as in the case of the Roman Empire and the Germanic peoples along its borders. The Southern Slavs (Bulgars, Serbs, and, at first, Croats) were in the Byzantine sphere of influence. The Eastern Slavs were affected by the Khazars and other steppe cultures, and by the Islamic states of central Asia. In the ninth century raiders and traders from Scandinavia played a crucial role in the formation of the Kievan state (see Rus; Vikings). The expansion of the Franks under the Carolingian dynasty influenced the Western Slavs.

Slavs south of the Danube were at the forefront of developments over all Slavic lands from the eighth century. The scarcity of Slavic material remains in the Balkans ends for the latter seventh century and beyond as villages or hamlets of that age and later have been uncovered. They consisted of a few sunken-floored huts that were being replaced as they deteriorated, so that the same settlement sites were used for several centuries. This stabilization of settlement coincides with the emergence of tribes documented in Byzantine sources. Perhaps because the Slavs first crystallized as an ethnic group in the context of larger confederacies of groups, first on their own and then as part of the Hunnic and then Avar confederacies, the new tribes south of the Danube soon formed larger coalitions, such as the Seven Tribes (or Clans), who lived along the southern bank of the Lower Danube. The name given by the Byzantines to Slavic lands in the Peloponnese of Sclavonia terra may document an organization of tribes that had joined to combat the Byzantines.

This self-organization ended as the Bulgars overran the territories of the Seven Clans and the Sieverzane in the process of creating a powerful khanate. However, as they had with the Avars, the Slavs were able to retain their cultural identity under the Bulgars, possibly because of the usefulness of their language as a lingua franca for all the groups that were under Bulgar domination. Slavic elements played an important role in the distinctive Bulgarian ethnicity that later emerged.

Not until the mid-eighth century as internal political turmoil ended were the Byzantines able to mount a serious attack on the Bulgars. In 756 they launched the first in a series of bloody campaigns over several dozen years that ultimately failed. The continued strength of the Bulgar khanate allowed the Bulgars to participate in the war of the Franks against the Avars in 793-796. The collapse of the Avar hegemony gave the Bulgars control of large areas of Transylvania and part of the Carpathian basin, while the Carolingian Franks’ power stopped short of the great bend of the Danube east of Vienna. The Bulgar polity became increasingly centralized under Khan Omurtag in the ninth century. The enormous territory of the khanate was divided into 11 areas, each with its own governor appointed by the state.

Although many Slavs were resettled in territories apart from their tribal homelands, breaking up earlier groupings, their continuing importance to the Bulgar rulers made their culture increasingly dominant in the khanate until in the ninth century a Slavic language (Old Bulgarian) became the state language. The government of the khanate was modeled on that of the Byzantines, and Bulgars adopted many elements of Byzantine culture. Thus the Bulgarian state lost its nomadic character—large urban centers, as with the Byzantines, played a central role in society

Contacts of Khan Boris with the Frankish king Charles the Bald and with the East Frankish kingdom seem to have impressed him with the benefits of religious unity in states; religious dissension in his realm had become troublesome, and he accepted Christianity, ultimately of the Byzantine creed. The liturgy was conducted, however, in the Slavic language. Boris then forcibly converted his subjects, including the polytheistic pagan Slavs.

Southern Slavs outside the Bulgarian Khanate

The rejuvenated strength of the Byzantines in the eighth century, although it proved inadequate against the Bulgars, did enable them to retake lands in southern Greece from the Slavs.

In 782 Constantine VI reconquered Hellas and then took the Peloponnese, creating a new theme there. In spite of this some Slavs were able to retain their autonomy and culture.

Slavic areas in the northwest Balkans were the scene of a power struggle between the Byzantines and the Franks from the end of the eighth century and fell under the domination of the Carolingian Empire, although indigenous leaders were allowed to continue to rule semiautonomously, subject to Frankish colonization. Carinthia in the eastern Alps, in which Slavs and indigenous Germanic peoples had joined into a distinct ethnicity, were under the domination of Bavaria and in the ninth century of the Carolingian Empire. The name of modern Slavs in this area, Slovenes, was not used until the 16th century; earlier names given them in medieval Latin documents include Sclavi and Sclavini, as well as Vinadi and Vinades.

Another group in the Balkans who lived alongside Slavic groups without joining them were the Albanians, apparently the remnants of the Illyrians who had lived there long before the invasion of the Romans, since at least the middle of the first millennium B. C.E. The Albanians lived scattered throughout the Balkans in small settlements, where the centuries of invasions had driven them.

With the final collapse of Avar power in the 790s Slavs moved into Lower Pannonia in the great bend of the Danube, among them Croats and Obodrites from the region of the Elbe River. Upper Pannonia to the west, the region around Vienna, remained under Frankish domination. By the latter half of the ninth century the Slavs there had organized themselves into a polity under Prince Pribina, who was in effect a vassal of the Carolingian king Louis the German, who had given him lands along the Zara River. Pribina encouraged colonization of forest and swamplands and showed his allegiance to Louis by accepting Roman Christianity and becoming part of the diocese of Salzburg. His son, under the influence of Slavic missionaries, accepted the Slavic rite of the Byzantine Church. This area was devastated by the Magyars in the 890s and later became the core of the Hungarian state.

The distinction between Eastern and Western Slavs has received much attention. But before the ninth century the cultures east and west of the usual dividing line drawn along the border of Poland and the former Soviet Union were

This pagan obelisk was constructed by the Slavs. (Drawing by Patti Erway)

Relatively uniform. The division seemed more of a “back-projection” into the past based on subtle differences in pottery types that are often more in the eye of the beholder than real. Soviet and Polish archaeologists working together to interpret material from this period agreed to demarcate the boundary between cultures as being along the Bug River—the modern boundary between their two countries, which again raises the question of how valid a division this was in the period of the early Slavs.

The expansion of the Germanic-led Rus, from the end of the ninth century, began to foster a markedly distinct cultural pattern in the east. Earlier, in the eighth century Slavs in the region that would become the Kievan state lived in forest steppe zones west and east of the Dnieper. These territories on each side of the river differed in their settlement patterns, and the region to the west seems to have become Slavic several centuries earlier than that to the east. The forest zone to the north had more sporadic Slavic settlement.

World History

World History