In October 1944, Congress converted the Office of War Mobifization (OWM) into the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion (OWMR). Where the OWM had been responsible for coordinating the mobifization of America’s economic and industrial resources for Worfd War II, the OWMR was charged with reconverting the economy to a peacetime basis.

In late 1943, as an Allied victory in World War II became more certain, Congress began to consider plans for an agency that could oversee the difficult problems of reconversion and DEMobifization. Congress wanted an organization that could determine the best way to curtail wartime production, relax rationing and other wartime controls, settle wartime contracts that were no longer needed, dispose of surplus government property, and help American industries resume producing civilian products. Moreover, Congress wanted this agency to be created through congressional legislation, not executive order, because the presidency had grown extremely powerful during World War II, and Congress wanted to reassert many of the powers it had given to Frankfin D. Rooseveft during the war.

In what became known as the “war within the war,” demobilization and reconversion involved extremely controversial issues. Liberals and FABor hoped that an early and incremental reconversion would help protect workers’ wartime jobs as production fell off. On the other hand, the military feared that reconversion would hamper wartime production and wanted to delay reconversion as long as possible, or at least until Germany was defeated. Large wartime contractors also wanted to delay reconversion, because they did not want to give competitors a head start in resuming civilian production. They also did not want to terminate wartime contracts without receiving generous compensation from the U. S. government.

As labor had feared, the so-called human side of reconversion, such as the training and placement of discharged workers and returning veterans, took a back seat to the interests of the military and big business. The OWMR allowed war manufacturers to buy government-owned factories and other surplus property at greatly discounted rates, offered them lucrative bonuses to terminate wartime contracts, and protected them against competitors.

James F. Byrnes, who had been the highly successful director of the OWM, became the first director of the OWMR, ensuring continuity in the agency’s operations. The OWMR was effectively terminated in December 1946.

Further reading: Herman Miles Somers, Presidential Agency: OWMR, the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950).

—David W. Waltrop

Okinawa (April-June 1945)

On April 1, 1945, with Japan near defeat in the Worfd War Ii Pacific theater, the United States invaded the Japanese island of Okinawa. One thousand miles from Tokyo and just 350 miles from the Japanese home islands, Okinawa could provide a base both for staging an anticipated amphibious attack on Kyushu (the southernmost home island) and for launching air attacks on Japan. Understanding Okinawa’s strategic value for the defense of the home islands, Japan had heavily fortified the island and placed some 100,000 troops upon it. The battle became one of the bloodiest of the war, both on the island and in the waters offshore.

The American invasion, launched by an enormous U. S. Navy fleet including more than three dozen aircraft carriers, came on April 1, 1945, with amphibious craft landing two divisions of U. S. Marines and two divisions of U. S. Army troops. The bloody, brutal battle lasted nearly three months. Because the Japanese stayed entrenched in heavily fortified blockhouses, caves, and pillboxes, U. S. troops had to move inland before the fighting actually started. The Americans, who ultimately outnumbered the Japanese by roughly two to one, moved forward relentlessly, using their enormous arsenal of weaponry and firepower and both inflicting and taking huge losses. The navy and the U. S. Army Air Forces launched thousands of aircraft sorties in support of the ground troops before and during the invasion. By May, the Americans had pushed the Japanese back to the southern part of the island, and after weeks more of heavy fighting, U. S. forces broke through the Japanese fortifications. The battle officially ended on June 22, but some fighting continued beyond that date.

Two aspects of the Japanese resistance were especially dramatic. First, as at Iwo JiMA, Japanese soldiers fought tenaciously to their deaths, typically refusing to surrender or be taken prisoner. Thousands committed suicide. Second, waves of Japanese kamikazes, suicide planes that dived into American ships, caused enormous damage. In all, the U. S. Navy took more losses than in any other battle of the war—one-fifth of its total wartime casualties—at Okinawa, losing 36 ships, 760 aircraft, and 4,900 men. Another 368 ships were damaged. On land, the United States took some 40,000 combat casualties, including more than 7,000 dead; one out of every seven marines killed in the war died on Okinawa. The ferocious Japanese resistance and the large American losses at Okinawa, the last major battle of the war, reinforced the perception that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would be enormously costly in lives. It thus contributed to the American use of the atomic bomb to bring the war to an end.

Further reading: Gerald Astor, Operation Iceberg: The Invasion and Conquest of Okinawa in World War II (New York: D. I. Fine, 1995); Hiromichi Yahara, The Battle for Okinawa (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995).

Owens, Jesse (James Cleveland) (1913-1980) Olympic medalist in track and field

Jesse Owens was a phenomenal track and field athlete who earned a lasting place in American history as the African American who embarrassed German chancellor Adolf Hitler and undermined his ideas of Aryan superiority at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. However, despite his exemplary

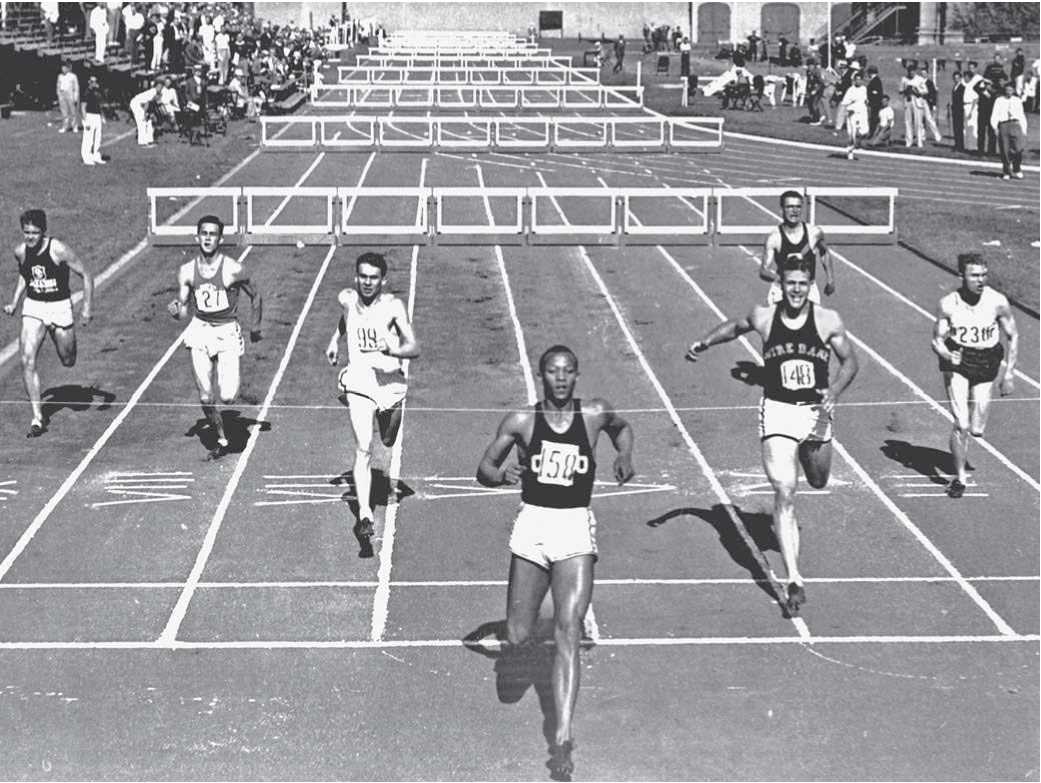

Jesse Owens winning the 220-yard low hurdles and setting a world record at the Big Ten meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on May 25, 1935 (National Archives)

Performance at Berlin and the fame it brought him, Owens had to deal with racial prejudice and economic difficulties at home.

James Cleveland “Jesse” Owens was born in Alabama into a family of sharecroppers in 1913. He moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1922. At age 13, Owens ran in his first race; by the time he had graduated from high school he was a nationally recognized sprinter. He entered Ohio State University without a scholarship, and, in a remarkable performance as a sophomore in 1935, broke three world records and tied another in just 45 minutes of competition. That same year, Owens married his high school sweetheart, Ruth Solomon.

In his junior year, Owens won a place on the United States Olympic team for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The Nazis had hoped to use the games to showcase their own racial superiority and they scoffed at the American team, especially the African Americans and Jews on it, as being racially inferior. Owens undercut the Nazis’ belief in their own racial superiority by capturing four gold medals. In winning three individual medals, he tied one Olympic record and broke two others, as well as breaking one world record. (Ironically, Owens and another African-American runner on the relay team that broke the world and Olympic records had replaced two Jewish athletes who had been removed to avoid offending the Germans.) After the American victory, Hitler responded by snubbing the victorious American athletes—Owens in particular—at the medal presentations, refusing to shake their hands and later walking out during some events. Owens became an overnight celebrity as the American press lauded his victories and the consternation they caused the Nazis.

Despite his performances in Berlin, Owens never was able to turn his athletic fame into financial success. He was forced to leave Ohio State before graduating to help support his own family. To earn money he became a playground janitor just one year after his Olympic triumph, and he gave up amateur track and field competition for show races against horses, greyhounds, cars, and trucks. Later, Owens became a disc jockey, ran his own public relations and marketing firm, and was active as a professional speaker. In 1976, President Gerald Ford awarded Owens the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his lifetime accomplishments. Owens died of lung cancer in 1980 at age 66.

World History

World History