It is difficult to discuss the ancient Greeks as a single people. For much of Greek history the Greeks lived in hundreds of separate, fiercely individual communities, all with strong nationalistic pride, and even strongly different dialects. Even the term Greeks is a late appellation, probably used by the Romans as Graeci (in the Greek form Graekoi) in reference to one small northwestern tribe. The Greeks themselves, when not identifying themselves as autocthonically Athenian, Spartan, or Corinthian, called themselves the sons of Hellen, after a legendary lineage for the Greeks found in the writings of the eighth-century B. C.E. Boeotian poet Hesiod. The strong individualism and chauvinism of the Greek city-states were in great part a consequence of the fragmentation of the Greeks’ homeland, either on mainland Greece, a peninsula crossed by high mountain ranges and with a rugged coast, or throughout the thousands of small islands of the eastern Mediterranean.

If by Greeks we mean all peoples who have spoken or speak a form of the Greek language, then the Greeks have by far the longest history of any other people in this book. The Linear B writings of the Mycenaeans, dating from the middle of the second millennium B. C.E., show

GREEKS

Location:

Greece; greater Mediterranean region; Asia Minor

Time period:

3000 to 31 B. C.E.

Ancestry:

Hellenic

Language:

Greek (Hellenic)

That they spoke a form of Greek that probably would have been somewhat intelligible to Greeks of the classical era. And from the time of the Mycenaeans and throughout Greek history to the present, the Greeks have been a very mobile people, trading and settling throughout the Mediterranean and in western Asia Minor and around the Black Sea. Thus through space and time numerous subgroups of Greeks have emerged, many of whom are discussed in separate entries in this book. In addition the devotion of Greeks to literature and learning, beginning in the time of Homer and Hesiod in about the ninth to eighth century B. C.E., has meant that an enormous amount has been written by ancient Greeks about themselves, their different groupings, and their ancestors. It has

Been a challenge to decide which of the very long list of peoples mentioned in Greek writings to include as entries in this book.

Homer mentions many groups, some of them tribes and some apparently language groups. The problem with the peoples mentioned by Homer is that many of them must have lived centuries before his time, and those centuries saw the disorders and dislocations of the Dark Ages, during which literacy was lost, so that Homer’s sources of information were all oral records passed down from generation to generation, leading to an unknown amount of distortion. And it must be kept in mind that Homer was writing fiction, not history in the sense we think of it. A great deal of his material came from myths. In addition, Homer had

Only a vague understanding of the people who created the pre-Dark Age civilizations: the Minoans and Mycenaeans. He assumed, as his contemporaries did, that the people who fought in the Trojan War, whom he calls the Achaeans, had a warrior society similar to that of the ensuing Dark Age. If, as is likely, the story of the Trojan War is based in part on folk memory of the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization in about 1200 b. c.e. (near the traditional date of the Trojan War), then Homer’s Achaeans were Mycenaeans and perhaps allies, whose society had gone far beyond a tribal warrior society to become a full-blown civilization. Much of what Homer understood of the peoples he wrote about is marred by a fundamental misconception.

Homer speaks of Ionians, Dorians, and Aeolians; these peoples seem to be based on language groups that had appeared by his time in various regions of Greece and Asia Minor. Historians before the 20th century have tended to accept Homer at face value concerning these peoples; archaeological discoveries since then have shown that it is very problematical to try to identify peoples known only from their material remains—pottery, weapons, dwellings—with those named by Homer. Thus we cannot trace with assurance the histories of the ionians and the rest much before the Dark Ages that ensued after 1200 b. c.e.

Homer also mentions numerous other peoples or tribes—from the Aethikes, Agraeoi, and Akarnanes to the Visaltes, Vistones, and

Yandes. The information he supplied on them in many cases included obviously mythic events and figures, including gods. Their stories may very well have come from geneaologi-cal histories of ruling families who usually traced their ancestry to a god or to a founder hero aided by a god or goddess (a common tradition among tribal peoples all over the world). An important part of the duties of the tribal bards whose epic tales formed the basis of the Homeric epics was just this keeping and retelling of the foundation myth of a tribe or people. Since it beyond the scope of this book to cover the mythologies of peoples, we have chosen not to have entries for many of the peoples Homer mentions.

Some terms used by Homer and later Greek writers, such as Pelasgians and Leleges, in addition to having a mostly mythic origin, have been variously applied, especially the former, their meaning changing over time. These two names have often been used in the past by historians as though they referred to real peoples; they have seemed to be important because Greeks used them to refer to earlier, pre-Greek inhabitants of Greece. Descriptions of them make them appear to have an early Neolithic culture—Pelasgos, the founder of the Pelasgians, was said to have invented the making of huts and an ancestor of the Leleges invented the grinding of corn. Yet since farming began in Greece around 7000 B. C.E., it seems unlikely that the information we have on these two peoples from the ancient Greeks thousands of years later has other than a literary or symbolic interest.

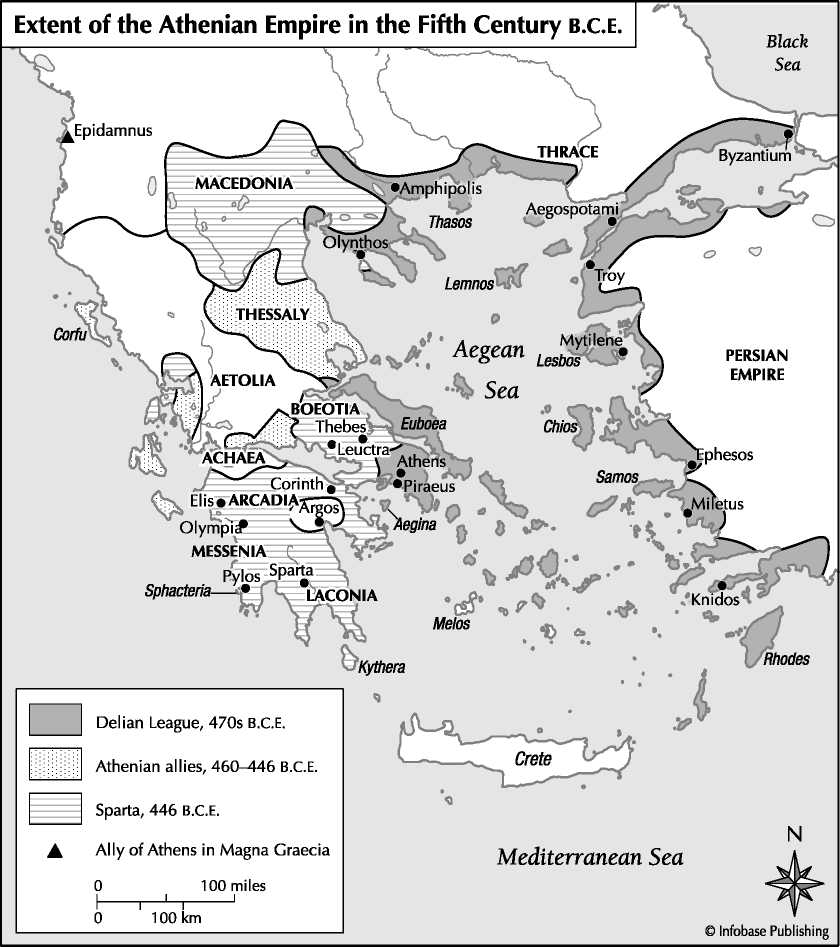

Numerous other peoples have been named by Greek historians in the centuries after Homer; Thucydides, for example, in his history of the Peloponnesian War mentions many allies of Athens and Sparta who took part in the war. Many of these, instead of being ethnic or tribal groups, were actually polities, each based upon a polis, or city-state, the basic political institution of classical Greece. They spoke Greek and considered themselves Hellenes, having the same gods and general culture as Athenians, Spartans, and other Greeks. For this reason they are not covered in separate entries; most of the information in the present entry applies to them. Similarly there are many regional names, such as Argives, Boeotians, and Arcadians, who do not have separate entries. During the classical period, a number of leagues, such as the Boeotian, Delian, and Epirote Leagues, were formed that brought different city-states together, mostly as allies in war. Again, they all shared a general Greek culture and outlook and are not given separate entries.

Archaeology, which has shed so much light on the early Greeks and their antecedents, has discovered the cultures of peoples who inhabited Greece and the Aegean in the remote past and who were almost unknown to historical Greeks. The Mycenaeans (named after the city of Mycenae, where the first traces of their culture was found) were one of these. Another group was the Minoans, who had a magnificent civilization on the island of Crete during the second millennium b. c.e. Archaeologists have found that peoples on the Cycladic Islands shared a Bronze Age culture much influenced by trade with the civilizations of the Near East; we have included an entry on these CYCLADITES.

In antiquity Greeks lived on the Greek peninsula, which makes up much of present-day Greece, the Ionian Islands to the immediate west, the Cycladic Islands stretching eastward to present-day Turkey, the islands of the Aegean, the islands of Crete and Rhodes, and the west coast of Asia Minor, from the Hellespont (the Dardanelles) north to the Carian peninsula in the south.

ORIGINS

The ancient Greeks spoke an Indo-European language; this fact does not clarify, however, when a Greek-speaking ethnicity emerged, because the timing of the emergence and spread of the earliest Indo-European language is still unknown. A prominent but much disputed theory maintains that the proto-Indo-European language spread throughout Europe with early agriculturalists and was adopted by indigenous peoples who took up farming. If this is true, a proto-Indo-European language could have arrived in Greece as early as 7000 B. C.E. when farming began there. A difficulty with this hypothesis is that it does not accord with known rates of language change unless it is assumed that this early Indo-European language remained static for thousands of years, which seems implausible.

Another more plausible view is that protoIndo-European, the ancestor of Greek as well as of most modern European languages, arose as a consequence of a series of socioeconomic changes in various areas of Europe that began in the fifth millennium B. C.E. in southeastern Europe, including parts of Greece, and spread across the rest of the Continent in succeeding millennia. These changes greatly increased contacts among groups who, for thousands of years since the adoption of farming, had led an isolated existence focused on farming villages. The Indo-European language may have arisen out of these new contacts.

One of these changes was the so-called secondary products revolution in which, for the first time, cattle, sheep, and goats (and possibly horses) were first used for more than their meat—for milk, wool, transport, and traction in pulling wheeled wagons (first documented in Sumerian pictograms of the first half of the fourth millennium b. c.e.) and plows. A consequence of this development was probably much greater mobility, which resulted in contacts among different peoples and cultures. The new products and agricultural surpluses that resulted from the use of the plow may have been used in trade.

Another development was trade in copper, which had begun to be worked in the Balkans in the sixth millennium b. c.e. and now was traded eastward toward the Black Sea region. In addition, development of the civilizations of Mesopotamia in the fifth and fourth millennia B. C.E. probably exerted an economic pull that tended to open up the closed, self-centered societies of the past in Greece and the Balkans.

Climate change, with several cold phases documented for the fourth millennium b. c.e., may have made southern Greece and the Aegean Islands more attractive than the plains of Thessaly to the north and may have fostered greater mobility. Many of the tells (mounds of decayed building material) that had been occupied for thousands of years were abandoned during this period.

A common form of handled pottery found throughout Greece and the Balkans to the Hungarian Plain indicates these new wide-ranging contacts, and the shapes of the jugs and cups of this type imitate metal vessels being made in adjacent areas of Anatolia, such as at the city-state of Troy The spread of such pottery may have accompanied the introduction in the fourth millennium b. c.e. of a new beverage, wine.

All of these changes could have facilitated the emergence and spread of the proto-Indo-European language in several ways. It could have become important as a trade language. It could have derived from the language of groups of newcomers, probably from the steppe regions north of the Black Sea where in earlier times the domestication of the horse had been developed, who now were using wheeled vehicles and whose language, as well as their new technologies, were emulated by native peoples. The rituals of drinking that seem to be documented by the array of jugs and cups found in burials, used for forging bonds between strangers meeting for the first time, may have been conducted in the lingua franca of proto-Indo-European (which in Greece would later develop into Greek), both wine and language used for communication and in themselves symbols of a wider world than the closed tell societies of the past. Such settlers need not have been great in number to have had a strong influence, and there is no convincing evidence that their arrival, if indeed it occurred, had the character of a massive invasion.

As do modern Greeks the ancient Greeks called themselves Hellenes. They themselves traced their origin to the northern region of the Greek peninsula, which they called Hellas.

LANGUAGE

One of the principal factors uniting the various Greek people was their language. This is plain from the Greek word barbarian, used for non-Greeks, probably derived in its original form bar-bar from the unfamiliar sounds of foreign languages. Many Greek words are cognate with English words, because of the relation of English to Greek as an Indo-European tongue. However, English borrowed many Greek terms and contains a plethora of words derived from Greek roots. These words are found in scientific and philosophical discourse, adopted as Europe moved into the Renaissance and hearkening back to the scientific and philosophical achievements of classical Greece.

Greek is an Indo-European tongue—and thus related to the Italic, Germanic, and Indic language families. It is plain from the intrusion of many non-Indo-European place-names in addition to religious vocabulary that Greek, while retaining its Indo-European form, mingled with local dialects of an earlier population.

After the Dark Ages Greek, in its earliest history, was divided into dialects that are said to mirror the early ethnic divisions of the Greeks: Doric (of the Dorians), Aeolic (of the Aeolians), and Ionic (of the Ionians, which was refined into Attic in classical Athens and immortalized in the great literature of that time). A closer study of Greek dialects reveals that spoken dialects were interwoven and spread over the Greek world, roughly divided into West Greek (primarily Doric) and East Greek (Attic-Ionic; Arcado-cypriotic, possibly an offshoot of Mycenaean; and Aeolic).

Alexander the Great, a Macedonian tutored by Aristotle, established his Attic Greek as the official language of state in his conquest of much of the early Mediterranean world and the Middle East in the fourth century b. c.e. Despite the collapse of Alexander’s empire into smaller kingdoms after his death, the principal language remained Greek, and Greek traders spread and thrived in such capital cities as Alexandria of Egypt, for which the era is sometimes named. Attic Greek developed into a simplified common tongue called Koine, a language maintained by the citizens of the eastern half of the Roman Empire and the language of much of the New Testament. Common Greek lasted throughout the ancient world until the sixth century c. e.

The learning of Greek was revived from the Renaissance through the Enlightenment, as the West began to rediscover its debt to the ancient Greeks in literature, thought, and learning.

The first civilization in the eastern Mediterranean was that of the Minoans, which began to develop in the third millennium b. c.e., probably under the influence of the Near East civilizations with whom they had contact through trade in tin and bronze. Crete formed an important way station for trade in the tin necessary to make bronze, which was introduced from the west, from sources in France and Britain (although the tin, a rare metal, passed through many hands before it reached Crete). The Minoans were able to make bronze with this tin by alloying it with copper mined on Cyprus, which was within the Minoan sphere, and traded it to the metal-hungry cities of Mesopotamia. Trade in produce, olive oil, and wine was also important. They developed a highly sophisticated culture based on magnificent palaces where large amounts of produce, accounted for on clay tablets with a script called Linear A, were stored in great clay jars. (The presumption that the writing on the tablets consisted of lists is based on analogy with the use of Linear B for such purposes and also on the fact that the earliest use of writing—in Sumer in Mesopotamia—was for recording lists of raw materials and products.)

The Minoans were long thought to be related to the original prehistoric inhabitants of the Greek world who migrated from Asia Minor and were supposedly characterized by their short stature and dark hair. Later Greek writers, such as Pausanius, believed that groups living in small wild communities in the hinterlands of the Greek world were the remnants of these original inhabitants related to the Minoans; they were called Pelasgians. The language of the Minoans was thought to be non-Indo-European, as evidenced in the names of certain gods (Poseidon) and in the names of places, such as Knossos. Their civilization was centered on Crete and on the island of Santorini. They built large multistoried palaces, had running water, and painted beautiful, colorful frescoes. Their religion was characterized by images of bulls and snakehandling priestesses.

The Minoans were capable seafarers and had an innovative method of farming that extracted the most yield out of the infertile coastal earth. They grew olives, grapes, and grain simultaneously, thereby distributing the work of cultivating them evenly over the growing season.

Minoan culture was highly influential on Greek speakers on mainland Greece, a chariot-using Bronze Age warrior society who may have begun to grow wealthy by preying on the lucrative trade of the Minoans. As would be the case later in Greek history, this society, while sharing the same basic culture, was centered in a number of cities; since the first of these to be excavated by archaeologists was Mycenae, this name was given to the civilization as a whole. The people are referred to as Mycenaeans. By the 15th century b. c.e. Mycenaean influence was felt throughout the Cyclades; a Mycenaean settlement with its own defensive walls has been found on the Asian mainland at Miletus. Trade routes, attested by finds of Mycenaean pottery, ran as far west as Sardinia, Italy, and Malta and as far east as the Levantine coast and Egypt. Twenty sites in Egypt, some far up the Nile, have produced Mycenaean pottery, and it has recently been suggested that figures of warriors on a papyrus from Tell el-Amarna might represent Mycenaean mercenaries. Meanwhile the Mycenaeans had close relations with the Minoans, their artists engaging in mutual emulation, to the degree that their products are nearly indistinguishable.

Minoan civilization repeatedly suffered catastrophic events that caused widespread destruction of buildings and cities; at least some of these probably were caused by earthquakes and volcanoes, although there is not enough evidence to show this definitively.

Mycenaean power increased at the expense of the Minoans, as through a combination of piracy, war, and diplomacy they encroached on the Minoan trade network and took advantage of the natural disasters the Minoans suffered. It is still debated whether the burning of all of the Minoan centers except Knossos, which occurred in 1425 B. C.E., was caused by an earthquake or by invading Mycenaeans. In any case after that time the Mycenaeans clearly ruled on Crete, as evidenced by the use of Greek for administrative matters, documented on numerous clay tablets inscribed with Mycenaean Linear B script, and by mainland-style chamber tombs containing weapon burials that were introduced.

The gold face masks and other exquisite artifacts found in the shaft graves at Mycenae and the massive palaces, tombs, and centrally planned agricultural estates, all of which must have required the labor of thousands, attest to the power and wealth of Mycenaean civilization. By the 13th century B. C.E., however, increasing instability can be seen in the fortification of many Mycenaean palaces; a defensive wall was built across the Isthmus of Corinth—whether as a protection against invasion from the north or from the south is unclear. The appearance at this time of a clearly intrusive form of pottery, called Barbarian Ware, and bronze daggers made in a northern style lends credence to the belief of later Greeks that a people speaking a dialect of Greek called Doric were involved in the collapse of Mycenaean civilization around 1200 B. C.E. The amount of this material does not support the idea of a wholesale invasion, however. The scanty archaeological evidence from this period makes dating of events highly uncertain. Some Mycenaean centers seem to have been rebuilt and then been destroyed again. The attacks suffered by the Mycenaeans should be seen in the context of a wave of destruction occurring at this time throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Both the Hittite Empire and Egypt were attacked by armies of what the Egyptians called the SEA PEOPLES, and other countries in the region were devastated as well.

The origins of the Sea Peoples are not known; some of them seem to have lived on Sardinia and Sicily, and the names given them by the Egyptians seem to derive from these islands’ names. It seems probable that the Sea Peoples originally were bands of pirates preying on the lucrative trade routes crossing the Mediterranean, similar to the Vikings of a later day. They may have joined to form armies in response to defensive efforts of the Mycenaeans and other states. They could have swept into their forces smaller groups of warriors, such as the Dorians; it is equally possible that Dorians had been hired by the Mycenaeans as mercenaries for defense; these two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and could both be true.

It is also possible that the various Mycenaean power centers—Tiryns, Athens, Argos, Mycenae—competed for access to trade routes, each trying to carve out its own sphere of power, even as the city-states of classical Greece did later. An early version of the Peloponnesian War played out among different Mycenaean powers may have been responsible for some of the damage that has been found.

Such competition could have intensified in times of climate change. The pattern of destruction could be explained by a prolonged drought that struck the areas of Crete, the southern Peloponnese, Boeotia, Euboea, Phocis, and the Argolid, where the destruction was greatest, but did not strongly affect Attica, the northwest Peloponnese, Thessaly, the rest of northern Greece, or the Dodecanese (Rhodes, Kos, etc.), which were largely spared. Meteorologists have shown that such a pattern of drought is entirely likely and has actually occurred in recorded times.

Dorians, Aeolians, and lonians

Many Greeks fled the Dark Ages that enveloped the mainland after the Mycenaean collapse, emigrating eastward through the Aegean and settling in Asia Minor. Between the rude and warlike Heroic Age, a poetic picture of the past drawn during the desperation of the Dark Age, and the heyday of learning and refinement of classical Athens, the two loci of modern understanding of the ancient Greeks, the Hellenes lived scattered through the Aegean, divided into three basic ethnic groups by dialect, culture, and location: the so-called Dorians, the immigrants who may have precipitated or at least participated in the collapse of the Mycenaeans; the Aeolians, earliest settlers of Thessaly, in northern Greece, and Boeotia, the territory of the classical city-state Thebes; and the lonians of Attica and Euboea, masters of the largest swath of Greek territory on Asia Minor and adjacent islands.

Archaeological evidence corroborates these legends of later Greeks that the Dark Ages saw significant migrations, with some regions left depopulated. The causes of these movements, as of the collapse of Mycenaean civilization that brought on the Dark Ages, are not certainly known—as noted, climate change, such as prolonged drought, the consequent economic regression, and war are all strong probabilities. The distribution of different Greek dialects of the period after the Dark Ages may document these migrations. The Greek spoken by the Mycenaeans seems to have been preserved in a dialect, called Arcado-Cypriot, shared by people in the remote mountains of Arcadia and on the island of Cyprus, strongly suggesting that Mycenaean refugees fled to both these places. In the former Mycenaean region Doric predominated.

The material remains of newcomers here at the time of the demise of Mycenaean civilization do not seem to document a large-scale movement of people, as there is so little of it. An explanation for this scarcity of material remains may be drawn from an analogy with the third-century b. c.e. invasion of Anatolia by Celts and the sixth-century c. e. invasion of Greece by SLAVS. In both these cases, which are known to have occurred from historical accounts, the invaders left almost no archaeological traces. What seems to have happened is that the invaders, whose culture was much less advanced than that of the inhabitants of the territory they were invading, quickly adopted elements of this new culture, thus becoming indistinguishable from the natives at least as far as material remains are concerned. The handmade burnished pottery found on several 12th-century sites, called Barbarian Ware, shows the process of acculturation of the invaders of Mycenaean Greece. The makers of this pottery at Tiryns soon began imitating Mycenaean pottery shapes with their handmade pottery. Production of large amounts of sophisticated, wheel-thrown Mycenaean pottery continued for a while after the destruction of the palace at Tiryns, after a time possibly by the invaders.

On the other hand it has been shown repeatedly throughout history that barbarian raiders on complex societies, such as the Vikings who raided northern Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries C. E., can have a destructive effect disproportionate to their numbers. The spread of the Doric dialect could have occurred among the peasant farmers in the Peloponnese after the demise or departure of their Mycenaean overlords. The speakers of Doric probably had an egalitarian warrior culture similar to that of many such cultures, from the Bronze Age Bell Beaker culture, to the Iron Age Celts, early Germanics, Slavs, and others. A fusion of cultures may have taken place.

Although the simple material culture of Doric speakers soon disappeared under late Mycenaean influence, Greeks in formerly Mycenaean areas may have adopted the Doric dialect and social structures. Pottery similar to the coarse Barbarian Ware of the Dorians has been found on the middle Danube in present-day Romania, suggesting either that they originated there or that they passed through the region. A pottery assemblage called Coarse Ware, similar to Barbarian Ware, is found near Troy from the time of its destruction. It is thus possible that Doric speakers took part in the invasions of the Sea Peoples who were attacking the Hittite Empire in Asia Minor and Egypt at the same time and who were probably responsible for Troy’s destruction. The Doric dialect was spoken in Crete and across a wide area of the southern Aegean, in Rhodes, and on the southwestern tip of Asia Minor.

In the Athenian region of Attica and the island of Euboea after the Dark Ages a different dialect was spoken: Ionic or Ionian. Although Athenian tradition maintained that Athens never fell to invaders, Mycenaean civilization ended here at the same time as in other areas of Greece. It is possible that the Ionian dialect was introduced to an Attica suffering from economic distress and depopulation, caused by the Mycenaean systems collapse, by outsiders accustomed to a simpler way of life independent of long-distance trade and the agricultural central planning engaged in by the Mycenaeans. Able to support themselves with subsistence farming and simple craft goods, Ionic speakers could have taken advantage of the depopulated landscape. As in the case of the Doric dialect on the Peloponnese Ionic together with the lifeways of its speakers could have been adopted by the local peasantry of Attica and Euboea who had been left to their own devices by the collapse of Mycenaean authority In the 10th century b. c.e. Ionic speakers seem to have migrated to Asia Minor, colonizing a region later named after them, Ionia.

Another distinct dialect of later times was Aeolic or Aeolian, spoken in the Boeotian plains and Thessaly and later in Asia Minor along its northern coastline.

End of the Dark Ages

The Dark Ages were not uniform everywhere in Greece. In spite of the loss of the Mycenaean trade network, trade on a more sporadic level apparently continued. Traders in the settlement of Lefkandi on the Euboean coast off the Greek mainland resumed activity after a brief lapse in the 12th century B. C.E., trading with Cyprus and the Phoenicians on the coast of the Levant. Rich burials with gold grave goods attest to the wealth of the elites of Lefkandi. The settlement flourished until about 825 b. c.e. At Lefkandi the earliest evidence of a revival of wealth beginning to approach that of the Mycenaeans has been found. In a burial dating from between 1000 and 950 B. C.E. the cremated remains of an apparent chieftain were buried alongside the body of a woman bedecked in gold and four horses in an apsidal tomb (whether built for this purpose or adapted from a prior use is uncertain) and covered with a mound.

Within a century other Greek trade cen-ters—Athens, Tiryns, and Knossos—were competing with Lefkandi for the eastern trade. A major stimulus for this competition were the Phoenicians, who may have been expanding their trade networks under pressure from their Assyrian overlords. By about 850 b. c.e. other trade centers had appeared on Euboea, and by 825 B. C.E. strong Greek influence was being felt at the port of al-Mina at the mouth of the Orontes River on the Levantine coast, although whether Greeks had actually settled there is in dispute. The goods Greeks received from the East are clear in the archaeological record— textiles, carved ivory, objects of precious metals, as well as iron ore and other metals. The Greek exports are uncertain—perhaps slaves, captured on raids in the north, and agricultural surplus. Some Euboean pottery from about 925 B. C.E. has been found in Syria.

The pace of change increased dramatically in the eighth century b. c.e., in part driven by population growth. Land that had lain unused since the 12th century b. c.e. was again under cultivation. Increase in wealth led to development of craft working in metals and pottery. Greek pottery, which up to now had been made mostly for domestic markets, attained a level of quality that made it desirable abroad, as attested by finds over a wide region of the Mediterranean. An increased pace of shipbuilding is a sign of expanding trade activity.

At this time the Greeks spread throughout the Mediterranean world, as merchants, mariners, and mercenaries; as artisans to paint and sculpt for Eastern satraps; and as court doctors.

Population growth also led to emigration. The earliest Greek colonies were those of the Euboeans in the west. Naxos was established at the first landfall in Sicily in 734 b. c.e.

(according to the fifth-century b. c.e. historian Thucydides). By the end of the eighth century B. C.E. Sicilian settlements created by the Euboean city of Chalcis lined the strategically important Strait of Messina. Syracuse, with the best harbor on the island, a secure water source, the spring of Arethusa, and fertile land nearby, was settled by the city of Corinth in 733 B. C.E. People from the northwestern Peloponnese founded cities on the coastal Italian Peninsula, and the Spartans founded there their only colony, Tarentum.

As the Greek presence in the western Mediterranean steadily grew, tensions with the Phoenicians increased. The latter had colonized the west coast of Sicily; now Greeks from Rhodes tried to settle in their territory, sparking clashes in 580 b. c.e. Settlers from Phocaea in Asia Minor who also moved west in the seventh century were the last contingent of Greeks who were able to find a place to colonize, but to do so they were forced north up the west coast of Italy past territory of the Etruscans, then along the south coast of France, where, in about 600 b. c.e., they founded Massilia (or Massalia, present-day Marseille) near the mouth of the Rhone River. Trading expeditions north up the Rhone River brought Phocaean traders in contact with Hallstatt period Celts, whose eagerness for Greek products—wine, pottery, and fine met-alwork—would have an enormous influence on their society, with momentous repercussions for the world of Mediterranean civilization. Phocaeans also moved into the northern Iberian Peninsula, founding Emporion (modern Ampurias).

Persian annexation of Phocaea caused another influx of citizens to the west in the 540s B. C.E.; they had to bypass land already taken by their fellow citizens, but ingeniously they settled on the island of Corsica, founding Alalia, which allowed them to trade directly with southern France and Iberia without going through the Etruscans. This situation was intolerable to the Etruscans, who convinced Phoenicians to join them in ejecting the Greeks from Alalia. By the end of the sixth century B. C.E. competition among Greeks, Phoenicians, and Etruscans had resulted in separate spheres of trade dominance for the three groups.

Euboean Greeks also looked north along the coast of Thessaly and beyond, probably in part for timber for ships, but also for arable land; parts of Macedonia became important for the production of wine. Farther east Greek settlement in the territory of the Thracians met

Rytheas: Scholar and Explorer of Europe

Pytheas was born in the early fourth century B. C.E. in the Greek colony of Massilia, now Marseille in southern France, which at that time was surrounded by Celtic peoples. He received an education in mathematics and astronomy; his teacher was Eudoxos of Cnidos, a student of the philosopher Plato. Pytheas is known to have used astronomical observations to determine the latitude of Massilia and became an accomplished navigator.

In about 325 B. C. Pytheas set out from Massilia on a voyage to explore the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Strait of Gibraltar. He probably had backing from the merchants of Massilia, who were interested in establishing a direct sea route to tin and amber sources in northern Europe. At that time Greek mariners had been prevented from venturing into the Atlantic Ocean by the Carthaginians, who maintained a naval blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar. The Greeks had been further discouraged by reports of the hazards of the open sea, including sea monsters. Carthage, then engaged in a war with Rome, had temporarily left the Strait of Gibraltar unguarded, allowing Pytheas to pass through.

Pytheas sailed along the south coast of present-day Spain through the strait and into the Atlantic, then northward along Spain’s and France’s west coasts. He eventually reached the coast of Brittany, which he accurately described as a peninsula. From there he crossed the English Channel and landed on the coast of Cornwall, near Land’s End. He established friendly contacts with the ancient Cornish, who, as tin miners and smelters, had frequent contacts with foreign traders that, Pytheas later noted, had made them less warlike than other Britons. He ventured inland and noted other aspects of life among the Britons, including the process through which alcoholic beverages were made—beer from fermented grain and mead from honey.

Pytheas next sailed northward along Britain’s west coast, sighted Ireland, and rounded the north coast of Scotland. He heard reports there of an island called Thule, a six-day sail to the north, which he believed to be the northernmost point on Earth. He attempted to reach Thule but was forced back by icebergs and dense fog. Pytheas later reported on the great differences between the lengths of day and night in the north, indicating he may have approached the high latitudes near the Arctic Circle or at the very least reached as far north as the Shetland Islands or the south coast of Norway near Bergen.

Pytheas completed his exploration of Britain by sailing down its east shore, thus completing one of the first circumnavigations of the island. He is thought to have proceeded across the North Sea in search of principal sources of amber. He possibly sailed around the Jutland Peninsula (present-day Denmark) and entered the Baltic, sailing along its south coast along the coast of present-day Germany as far as the mouth of the Vistula in present-day Poland. He explored a number of islands, and then returned to open waters and followed the Atlantic coast back to the Mediterranean and Massilia, completing a sea journey of several years. After Pytheas’s expedition the Carthaginians again closed off the sea route to the Atlantic. Seaward exploration of northwestern Europe was not resumed until Julius Caesar reached Britain some two centuries later.

Pytheas wrote an account of his voyages called On the Ocean in about 319 B. C.E. Although the work did not survive, his observations were cited in the works of geographers of later centuries, including Polybius, Strabo, and Pliny. Strabo in particular rejected as fabrication much of what Pytheas described on his voyage. However, his contributions to ancient knowledge are evident. He demonstrated that the sea route to the tin mines of Cornwall and amber sources along the Baltic was impractical compared to the much-shorter overland routes across present-day France and Germany. He also demonstrated that the supposed terrors of the Atlantic were imaginary, probably invented by the Carthaginians to discourage Greek maritime expansion. He established that the North Star did not lie above true north and that the Moon has a great effect on the tides along the North Atlantic coast of Europe, a phenomenon that was much less evident in the Mediterranean basin. Moreover he made accurate anthropological observations on northern peoples. Pytheas is considered the first scientific explorer.

With opposition; therefore Greeks colonized the island of Thasos in 680 B. C.E. At about the same time colonists from Megara, a city on the Greek coast west of Athens, had ventured into the Dardanelles, the entrance to the Black Sea; here they founded first Chalcedon on the Asian side of the straits, then in 660 B. C.E. Byzantium on the European side. The site of Byzantium was excellent, with a fine harbor and a fortifi-able headland protected by the sea. This was to be the location of the Roman eastern capital, Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Despite initial hostility from Thracians and Scythians, Greek goods began to be traded up river valleys as far as present-day Russia, and their artworks heavily influenced the Scythians, who became excellent workers in metals. The Greeks received in return fish, hides, and slaves.

Greeks from Thera founded Cyrene in North Africa, located farther inland than was usual for Greek colonies. Cyrene became one of the richest agricultural areas in the Greek world, where sheep, horses, and grain were raised. Archaeological and other evidence from Cyrene suggests that Greeks there intermarried with native Libyans and adopted some of their cult practices. Intermarriage may have been typical for Greek colonists elsewhere, because the first settlers of new territories probably included few women.

Exploration and colonization both enriched Greek culture. In about 325 B. C.E. a Greek named Pytheas engaged in a great voyage of discovery, setting sail from the port city of Massilia and passing through the Strait of Gibraltar (called in his time the Pillars of Herakles) into the Atlantic Ocean and traveling northward, visiting the British Isles and the North and Baltic Seas (see sidebar). His account of the voyage was used by a number of ancient scholars as a resource.

The Greek colonies on the edges of the known world provided Greek scholars with the opportunity to observe other lands and peoples. One such was Strabo, born in Pontus south of the Black Sea (see sidebar, p. 351).

In the late eighth century B. C.E. war began between Eretria and Chalcis, the two main cities of Euboea, over control of the rich Lelantine plain that lay between their territories. As in the fictional Trojan War and later conflicts in the classical period, the two rivals were soon joined by many cities of the Greek world, who allied themselves with one or the other Euboean city, a sign that the fierce competitiveness that probably characterized the

Strabo: Traveler and Geographer

Strabo was born at Amasia in Pontus, a region south of the Black Sea in present-day Turkey, in 64 or 63 B. C.E. He studied history and philosophy in his native city and, it is thought, in Greece, Rome, and Alexandria as well. He also traveled widely, claiming to have visited lands in western Asia, southern Europe, and northern Africa, as well as islands in the Mediterranean. In 25 or 24 B. C.E. he explored the Nile River as part of the expedition of Aelius Gallus, prefect of Egypt. For most of his life he lived in Rome.

Only fragments survive of Strabo’s work in 47 volumes referred to as Historical Sketches; many later authors quoted it, however. The extant Geography, a work in 17 volumes (with only part of the seventh volume missing), describes the lands of the known world as far east as India. It expands on facts and observations from his own travels, from Roman military expeditions, and from works of earlier Greek writers, such as Homer, Eratosthenes, Polybius, and Poseidonius. Strabo was skilled at selecting and organizing useful information, and his work has Greek scholar Strabo holds a globe served as an invaluable resource on of the world in this print from 1584. the peoples of the Augustan Age. (Library of Congress [LC-USZ62-He died sometime after 23 C. E. 99999])

Mycenaean period continued to be a major factor in post-Dark Ages Greece. The warriors who participated in the war were of the elite classes who had grown wealthy in the Euboean trading enterprise; the two sides even made an agreement to exclude the use of ignoble weapons such as arrows and stones in favor of face-to-face combat.

Little is known about this war; it seems to have ended with the exhaustion of both cities, since neither enjoyed again the same dominance as each had in the past. Eretria survived mostly through its association with allies in the Black Sea region, and Chalcis relied on its alliance with Corinth, which now emerged as the new power. When the Euboean city of al-Mina was sacked by the Assyrians, the Corinthians rebuilt it. Corinth, which had been no more than a cluster of villages as late as the eighth century B. C.E., may have gained territory on the Isthmus of the Peloponnese as a result of the Lelantine War, which would have facilitated its trade enterprise by providing an alternate eastward route to the voyage all the way around the rocky and dangerous Greek (Peloponnesian) south coast. This would explain Corinth’s rapid expansion in the seventh century b. c.e. Corinth was known as a center of shipbuilding, where shipwrights improved the 50-oared penteconter, a type of galley ship designed by the Phoenicians, by making it narrower and faster and giving it a projecting keel beam that was sheathed in bronze for use as a ram. Corinth thus became a dominant sea power.

The ruling clan of Corinth, the Bacchiadae, differed from more traditional aristocratic families in not despising craftsmen, but instead offered them generous patronage. As a result foreign craftsmen flocked to the city. Pottery production, in particular, flourished; Corinthian pottery in great amounts has been found all over the Greek world. It is notable for its eastern characteristics, since Corinth was more receptive to eastern influence than Athens.

Age of Tyrants

In the seventh century b. c.e. tensions between the aristocracy and the populace with its growing power had grown in many city-states. Such conflicts were exploited in a number of cases by ambitious individuals, paradoxically often aristocrats themselves, who championed the cause of the common people. Corinth was the first tyranny, followed by its neighbors Sicyon and Megara. The first Athenian tyrant was Peisistratus, who seized power permanently in 546 B. C.E. after several abortive attempts. There were tyrannies on the Aegean islands of Samos and Naxos, for instance, and in the Ionian cities along coastal Asia Minor. Most tyrannies were short-lived, as their emergence depended on special historical circumstances: the struggle for political power in cities between the old landed aristocracy and the rising merchants and traders, who in many ways resembled the middle class of the modern era. Most tyrants gained power by backing the latter and taking steps to weaken the aristocracy Once this was accomplished, however, citizens of the new middle class were unwilling to divide their power with an autocratic leader.

In Asia Minor and the islands of the Aegean art, architecture, poetry, and philosophy began to flourish. Out of this period and region arose epic poetry and Greek lyric poetry Presocratic philosophers, such as Anaximander and Heraclitus, investigated the nature of the universe. City-states developed and grew, under kings, then oligarchies, finally under tyrants. These city-states formed leagues for defense—the Dorian League and Ionian League—and sent out colonizing expeditions, renewing contacts with their kinspeople in Greece.

By classical times power and prestige had shifted from Asia to the Athenians of Attica and to the Spartans on the Peloponnese. Each claimed through a complex mythical web to be the original ancestors of Greeks on Asia Minor; the Athenians claimed the ancestral Ionians as their forefathers, the Spartans the Dorians.

The site of Sparta has good natural defenses, probably the reason why it was a focus for settlement. The city emerged when villages scattered near the defensible area joined into a unified polis; the fact that through much of its history Sparta had a pair of hereditary kings suggests that the unification of Sparta resulted from an alliance between two powerful families. Spartan society was focused on war to a greater degree than that of any other Greek city-state, perhaps because Sparta had been born of a military alliance.

The Spartan kings had dual roles as religious leaders and generals of the army. These two roles are typical of other Indo-European peoples, although not always held by a single man; many Germanic tribes, for example, had a religious king called a thiudans and a war leader called a reiks. In general Spartan society was the most conservative in the Greek world, in a number of ways little different from that of the tribal Dorian past. The kings ruled with the aid of a body of 30 councilors, called the ger-ousia. As in most cities there was also a citizen assembly, who elected men to the gerousia by acclamation from among those who had reached the age of 60. The citizen assembly’s role appears to have been consultative, listening to proposals of the kings or elders and approving or disapproving them. This arrangement, too, had many similarities to the things of Germanic tribes, also consisting of assemblies of all the warriors no matter their rank, guided by councils of elders.

The warlike character of Sparta led to the city’s early expansion and absorption of neighboring towns and territories. In 736-716 b. c.e. the Spartans annexed the rich plains of Messenia to the west, Spartan citizens taking lands for themselves from the Messenians and reducing the latter, whom the Spartans called helots, to serfdom (as they also had the populations of other territories they had conquered earlier). The precariousness of Spartan control over the helots would have a profound effect through most of Spartan history. There is some evidence that in the seventh century b. c.e. a helot rebellion was not suppressed for two decades. Sparta may have been weakened at the time because of a conflict with the neighboring city of Argos, possibly the first Greek city to use hoplites, heavily armed citizen infantry. Hoplite armies were the most powerful forces in the Greek world, eventually adopted by every Greek city-state, including Sparta. Their hoplites may have allowed the Argives to inflict a devastating defeat on the Spartans at Hysiae in 669 B. C.E.

These reverses led to a complete reorganization of Spartan society As did most Greek city-states of the time, the Spartans recognized the necessity of building a hoplite army. The fundamentally feudal society of Sparta, all its citizens freed of the necessity to engage in economic activity, enabled the entire male citizenry to focus on war to the exclusion of everything else. Every Spartan man was assigned to a group of fifteen, called a mess or eating group, with whom he lived, trained, and went to war. This unit seems to have had its roots in the hall feasts of the warrior elite past. The Spartan army was tightly disciplined, and boys began their training in discipline and war at the age of seven, being subjected to harsh treatment to toughen them up.

Plato remarked that all education in Sparta was carried out through violence rather than through persuasion and that the emphasis was on producing hardiness through endless tests of self-reliance and endurance. At the age of 20 boys joined a mess, the syssitia, where they spent most of their time. Homosexual relationships may have been the norm. Men could marry, but all visits to their wives had to be conducted by stealth at night until they were 30. Even marriage ritual was conducted in such a way as to limit associations of home and the domestic side of life that would distract the husband from his primary duty: to fight. On the marriage night the bride was dressed in a man’s cloak and sandals and lay in an unlit room to receive her bridegroom.

In general the insecurity of Spartan society caused by the constant necessity to keep the helots in submission fostered a culture of extreme insularity, with military discipline aimed at minimizing individuality. Spartans called themselves “those who are alike,” an expression both of the suppression of individuality in favor of service to the state and of a sense of being surrounded by a hostile “other.” Spartan soldiers all wore red cloaks and long hair to assure uniformity. A man’s greatest glory was to die for the state; survivors of a defeated army were shunned. Literacy was not important in Sparta; writing was used only for international treaties, and Spartans were famous for their brevity of speech (the word laconic is from Lacedaemon, the name of Spartan territory), a habit undoubtedly inculcated in them from childhood, both signs that freethinking was discouraged by Spartan society

The Persian Wars

By the late sixth century b. c.e. Sparta was the most powerful of the Greek city-states, ruled by a pair of kings in an oligarchy. In Athens, the tyrant Peisistratus’s son Hippias sought help from Spartan forces to remain in power but was forced to resign in 510 b. c.e. Athenians sought protection against the Spartans from Darius I of Persia, but when the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor rebelled against Persian rule the Athenians decided to join them. This sparked the Persian Wars (490-479 b. c.e.).

In 490 B. C.E. Darius sent a fleet to capture Athens. At the Battle of Marathon the Athenian hoplites drove away the Persian army In 480 B. C.E. Xerxes I crossed into Europe with a huge army over a pontoon bridge to attack mainland Greece. Sparta led an alliance of 31 city-states against the Persians, and Leonidas I, king of Sparta, and his personal guard of 300 men, together with 5,000 troops from allied cities, faced a huge Persian army possibly as large as 200,000 men at the narrow pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas was able to hold off the Persians for several days, but finally, as Xerxes’s scouts found an alternate path over the mountain over which to send a flanking force, Leonidas sent away the allied troops and with his personal guard faced the Persians alone. The Spartans fought to the last man. The Athenians had abandoned Athens by the time the Persians reached it, and the city was largely destroyed.

The Athenians, under Themistocles, defeated the Persians, even with their numerically superior navy, at Salamis, having lured the Persian ships into a narrow channel. In 479 B. C.E. the Greeks inflicted a decisive defeat on the Persians at Plataea, destroying a large part of their army.

The Rise of Athens

Supremely confident after naval victories against the Persians, and in spite of the fact that much of the city lay in ruins, Athens used its fleet to become a naval powerhouse, aiming to carry the war back to the Persians. Athens formed what is known as the Delian League with city-states in northern Greece, the Aegean islands, and the west coast of Asia Minor, where the Greeks were most vulnerable to Persian attack. (The treasury of the league was on the island of Delos.) Athens took control, exacting dues from member states in lieu of ships and crews. Athens surged in wealth and power by trading and raiding other states. The league developed into an empire for Athens, since the allies had almost no navies of their own. Athens refused to let states leave the alliance.

Pericles (see sidebar) was the leading Athenian politician of the 450s b. c.e., taking decisive steps to strip the Athenian aristocracy

Pericles: Statesman for the Ages

Pericles, the son of the army commander Xanthippus, was born in about 495 B. C.E. He was tutored by the philosophers Anaxagoras and Damon. Upon the banishment of Cimon in 461 B. C.E. Pericles was elected leader of Athens. The Delian League, established in 478 B. C.E. to unite various cities on the mainland with some on the Aegean Islands, prospered during his reign. In 446 B. C.E. Pericles defeated Euboea (modern Evvoia), which had revolted against the league, strengthening Athen’s dominance of the alliance. The next year he arranged a truce with Sparta. He also sent a fleet to secure the grain route between Athens and the Black Sea. At the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431 B. C.E. Pericles let the Peloponnesian army plunder the countryside while he gathered his countrymen inside Athens’s gates. An epidemic ravaged the overcrowded city, and resentment of Pericles grew. He was driven from office and tried and fined for misuse of public funds.

Reelected in 429 B. C.E., he died later that year, reportedly of plague.

Pericles, known for his statesmanship and eloquence, inspired what is known as the Age of Pericles. Among his achievements were government open to all citizens and payment for services rendered to the government. His public works program included restoring the temples destroyed by the Persians and building the Parthenon and Propylaea on the Acropolis. He supported the arts and befriended the historian Herodotus, the sculptor Phidias, the philosopher Protagoras, and the playwright Sophocles.

Outliving his two legitimate sons, he

Was forced to legitimize his son Pericles is depicted in this bust.

Pericles, whom he raised with his (Library of Congress, Prints and

Mistress, Aspasia of Miletus, a cul - Photographs Division tured courtesan. [LC-USZ62-107429])

Of its power, expanding the role of the democratic assembly in government, and promoting Athens’s dominance over the Delian League. A symbol of that dominance as well as of democratic pride was the Parthenon (from parthenos, virgin), a magnificent temple to Athena in part built with funds from the Delian League’s coffers, a fact bitterly resented by other league members. Pericles supported naval expeditions to Phoenicia and the Black Sea and frequently confronted Sparta, which had a league of its own on the Peloponnesos. Eventually Pericles advised that war was being fought on too many fronts, and Athens signed a peace treaty with Sparta to maintain a grip on its empire. At the empire’s height there seem to have been some 150 subject states. Virtually every island of the Aegean was a member. Athenian control stretched along the Asian coastline from Rhodes up to the Hellespont, into the Black Sea, and around southern Thrace as far as the Chalcidice peninsula. Nearer home the cities of Euboea and the island of Aegina were members.

Athens put pressure on its shipping rivals, Corinth and Megara in the Peloponnese, which were key allies of the Spartans. This escalated into the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B. C.E.). Pericles conducted surprise naval raids on the Spartans, then retreated behind the walls of Athens when the infantry attacked. In 430 B. C.E. an epidemic started behind the walls, killing thousands, including Pericles himself, over a period of several years. The Athenians’ allies revolted against their demands for cash.

Finally in 415 B. C.E. Athens launched a foolhardy campaign against Sparta’s allies in Sicily, overconfident of their prospects for victory. The Athenians were defeated catastrophically at Syracuse in 413 B. C.E. Sparta meanwhile built a navy with support from Persia. In 404 B. C.E. the Athenians lost the war, after much attrition, the loss of its silver mines, and a devastated agriculture. The Athenian empire ended, and Sparta installed a puppet regime, the Thirty Tyrants. These lasted only a year, replaced when rebels restored democracy in 403 B. C.E. Athens rebuilt but was unable to gain its former power, and Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, and Athens contended throughout the first half of the fourth century B. C.E. in brutal indecisive warfare. Corinth and Thebes rose to power as the century progressed.

World History

World History