During the first half of the 19th century, cotton defined the South as no other crop did before or since. Its growing range and yield were enormous, encompassing at least a dozen states from North Carolina to Texas and producing at rates that doubled every decade between 1820 and 1860. Already by 1820, cotton accounted for nearly 50 percent of the value of U. S. exports. It also brought great growth to the region, as the population, despite the relocation of thousands of Native Americans, increased fivefold. During the 1840s and 1850s, the population grew from 7 million to 11 million. Among them were as many as 3.5 million slaves, whose labor was central to the success of mediumsized farmers and large planters alike. By mid-century cotton was indelibly associated with the southern economy, lifestyle, and political outlook, and for good reason: By 1860 the United States produced and exported 4.5 million bales of cotton (2 billion pounds), which constituted two-thirds of the world’s total cotton production and nearly 60 percent of the nation’s exports by value. And while 75 percent of all cotton was exported to England and the mid-Atlantic states, the remainder ended up in the textile mills of New England, where a cordial and profitable economic connection had evolved between factory and plantation owners.

Accounting for more than 65 percent of the world’s cotton by the 1850s, the south was a major contributor to the U. S. national ECONOMY. In 1855, David King published Cotton Is King, in which he noted that cotton was royalty, in constant international demand for textiles and other uses. The erosion of the practices that built an effective single-crop economy—on economic, political, and moral grounds—marked the later antebellum years and laid the foundation for the coming civil war. This dogged overreliance on a single crop, however, stagnated the southern economic infrastructure, especially compared with the rising industrialization and central financing of the North. This ultimately laid the seeds for defeat in the Civil War. But the cotton culture ran deep throughout the fabric of southern life, and it was not until 1865—and then at the point of Union bayonets—that “King Cotton” and the slavery sustaining it were effectively dethroned.

Before the early 18th century, tobacco and rice were the primary commercial crops in the South, and both depended on slave labor. Although the southern states of Virginia and Maryland had successfully raised tobacco in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with production levels climbing to what they had been before the Revolutionary War, by the 1810s and 1820s they had become transformed by cotton. Tobacco, which had yielded 15 percent of the value of U. S. exports in 1820 brought only 6 percent of that amount in 1845. Rice had also been an important export crop, but beginning at the end of the 18th century, exports stagnated and remained low until the 1850s. In the early 19th century, sugar developed into an important commercial crop, first in the Upper South and later in the Gulf region, and would be another slave-based crop that provided no economic reason for the South to free slaves, as would occur in the North during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

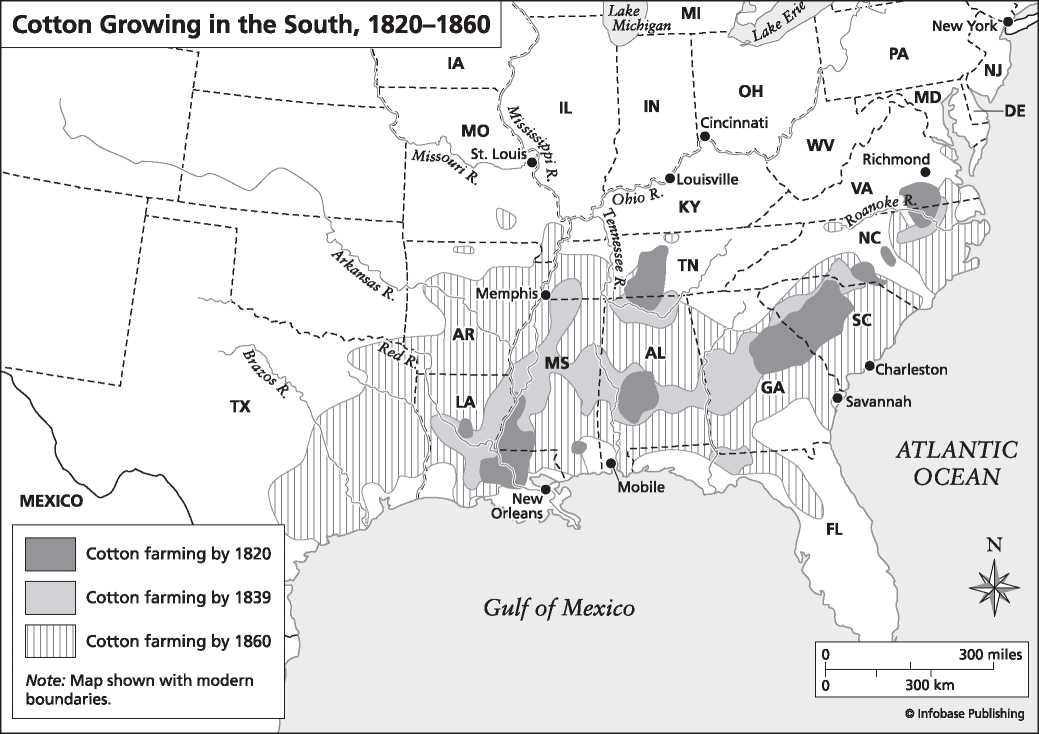

At the same time, a new crop was being grown: cotton. It arose to serve an increasing export market for textile businesses in the newly industrialized Britain. But the type of cotton being grown, long-staple cotton, could be raised successfully only in the sea-island areas of Georgia and North and South Carolina. Another variety, short-staple cotton, was more geographically adaptable but had gummy seeds that were too labor-intensive to remove by hand and keep the crop profitable. The success in 1793 of Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin, which removed seeds from cotton, transformed short-staple cotton harvesting and began its titanic expansion across the South and West. In 1815, southern cotton production stood at 150,000 bales (one bale equals 500 pounds); by 1826, it was 600,000 bales per year; by 1851, it had reached 2.4 million bales per year.

Since their initial migration south and west to Alabama and the western parts of the Carolinas, Florida, and Arkansas, white planters fought with several Native American nations including the Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw for

Control of the region. Agreements such as the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson ceded former Native American lands to the U. S. In the 1830s, nations in the Southeast including the Choctaw, Cherokee, and Chickasaw were relocated west of the Mississippi River, some traveling along the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma. Even nations that adopted settlers’ ways, such as the Cherokee, were forced to remove themselves from the South during the 1830s. Ironically, many of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes adopted slavery and cotton growing in their new homeland, a circumstance that contributed to their siding with the Confederacy in 1861.

At the same time (and continuing through 1860), up to a million slaves were brought to the South, particularly to the millions of acres of the soil-rich Lower South. To farmers and planters, slaves provided a secure, self-perpetuating source of labor that increased at the rate of 30 percent each decade between 1820 and 1860. Slaves were considered even more valuable to agricultural success than they had been two or three decades earlier, before the rise of cotton. As a result, the South considered any move away from slavery to be a threat to self-preservation. Accordingly, southern support for the emancipation of slaves nearly vanished. While in the 1820s southern antislavery societies outnumbered those in the North, they were virtually nonexistent in the South by the late 1830s. In addition, the number of slave states in the region more than doubled, from six to 15. Following the abolition of the African slave trade in 1808, there arose an equally insidious domestic slave trade, whereby surplus chattels from the tidewater regions of Virginia and Maryland were sold to new masters in the cotton-producing regions of the Old Southwest. Not only were slaves transported there in chains and work gangs, but their sale frequently involved the breakup of established family units. It is estimated that by 1860 nearly 1 million blacks had been forcibly relocated to a harsh existence in the Deep South.

Yet only a minority of the population was slaveholders, a number that decreased due to increased slave costs over the course of the 19th century. In 1850, 347,825 of 6 million white residents of the South owned slaves. Further, as fewer planters owned slaves, cotton production, property, and wealth became concentrated in those families holding the largest number of slaves. Of the 10,000 families holding 50 or more slaves, the wealthiest among them were the 3,000 families owning more than 100 slaves each. About 90,000 farmers owned between 10 and 99 slaves; about 255,000 other farmers owned fewer than 10 slaves. Two percent of slaveowners owned half of all U. S. slaves.

There was great variety among slave-owning cotton farms in the South. While the 3,000-4,000 large slaveowning plantations had a greater role in cotton production by mid-century, much of 19th-century cotton was grown on small to medium-sized farms with limited slave labor. For example, a middle-class planter might have 10-50 slaves on his farm, which, if managed correctly, could yield substantial profit; a workingman’s farm would have less than 10 slaves. Generally, such small farms were characterized by their overall poverty, with owner and slave working side by side in the field on cotton that yielded only $125 per year. As Mark Twain described it in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, this was “one of those little one-horse cotton plantations” with a “rail fence around a two-acre yard. . . [and] some sickly grass-patches in the big yard.”

Life on large plantations was vastly different. The family home on the site would have been fashioned in what architect Frederick Law Olmstead called “a Grecian style,” with wooden slave housing situated far from the house. Slave labor was monitored by the overseer, whom the plantation owner hired to discipline slaves and maintain profits. An intelligent and able slave was given the job of driver; he was the overseer’s closest subordinate and was responsible for managing the slaves. One common factor for all slaves was the long workday, which ran for 12-15 hours per day, and longer if the moon allowed.

The demands and rewards of the “King Cotton” economy resulted in a fivefold population increase during the first six decades of the 19th century, but it kept the South an unsophisticated agricultural economy. Because it produced few other goods, it needed to import goods from northern manufacturing states; and because prices for cotton fluctuated greatly, the South had little capital to invest in manufacturing and therefore had to purchase goods and rent storage space for cotton from northern suppliers on credit. In the 19th century, such practices left the South in a chronic state of financial instability. The social implications of the cotton culture were equally stark; the rise of large plantation systems retarded the growth and maturation of urbanized areas and, with it, viable banking and transportation systems. An unsavory result of this state of affairs was that yeoman farmers were forced to turn to their richer neighbors for assistance in marketing their produce. Given the near-total absence of social services, virtually every aspect of social life was the de facto domain of the landed gentry, including community services, education, and government. Church life was the only facet of private life available to non-slaveholding whites. This overt dependency stimulated the rise of a dominant planter class wielding political influence far in excess of its actual numbers, and it is no exaggeration to say that the abiding interests of the planters came to represent or embody the basic interests of the South in general.

Some southern spokesmen attempted to counter encroaching northern dominance by rallying the next generation to embrace industrialism. In 1849, according to an editorial in the Swmp-ter Banner of South Carolina, the current generation should feel compelled to cast aside the timeworn call to preserve gentility and prepare “the rising generation for mechanical business.” But it was too late to catch up to the urbanized, industrialized North. In the northeast, one-third of residents lived in cities and towns; less than 13 percent of residents of the Southeast were similarly urbanized. The distinction between industry and agriculture was similar: As late as 1860, 60 percent of northern workers were employed in nonagricultural jobs, while only 16 percent of southerners were employed in nonagricultural work. That meant there were 1.3 million industrialized workers in the North but only 110,000 in the South.

Meanwhile, the South encountered an immediate, chronic threat to cotton planting: overplanted, exhausted crop land. In 1826, the Upper, or old, South, accounted for more than half of cotton produced. But the cultivation of a single crop depleted the soil and reduced yields dra-matically—in some areas, up to 50 percent. In response, planters entered what would become a common situation: being compelled to move westward for fresh soil. In the 1840s and 1850s, planters and slaves from the formerly fertile cotton states of Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina moved to the rich Gulf and Mississippi River states of Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas. Over the next several decades, they moved even farther west, to Arizona and California.

While cotton production in the Lower South soon doubled or tripled the production of the old South, it resulted in wealth for only the few large plantations and farms, which were able to replenish their ranks of slaves from within. In response, smaller farms unable to find or afford slaves called for the resumption of African slave trade, which had been outlawed for several decades. This position, which stood in opposition to national law and Northern sensibilities, became one of the many factors that hastened the Civil War and brought an end to the “peculiar institution” of slavery and the cotton culture it supported.

Further reading: American Social History Project, Who Built America: Working People and the Nation’s Economy, Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 1 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989-92); David L. Cohn, The Life and Times of King Cotton (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956); Neil Foley, The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003); John Mayfield, The New Nation: 1800-1845, rev. ed. (New York: Hill & Wang, 1982).

—Melinda Corey

World History

World History