By November 11, 1918, most Canadians had had more than enough of involvement in foreign wars. That was doubly true of French Canadians. Yet, at the war’s end, Canada had assumed new obligations as a member of the international community. There was, as the prime example, the League of Nations in which Canada had been granted full membership. It very soon became evident that, for successive Canadian governments, membership was almost totally a matter of status. First Robert Borden in 1919 and then Senator Raoul Dandurand, speaking for the Liberal King government in 1922, made it plain that Canada lived “in a fireproof house far from inflammable materials” and felt no automatic obligation to the principle of collective security. High-sounding sentiments, even ambiguously phrased declarations of virtue were permissible; agreement to concrete action was something else. Like their southern neighbours, slumbering in isolation, most Canadians appeared to want a return to “normalcy.”

This same mood of withdrawal lay behind Canada’s pursuit of autonomy within

The British Empire-Commonwealth. The terms of Canada’s membership in the Empire remained almost as confused in 1919 as they had been in 1914, and almost no one in Canada was satisfied with that situation. The old pre-war divisions about the road to definition remained. But where Laurier had temporized, King was forced by events to decide. Meighen, as befitted a Conservative, attempted to follow Borden’s path: a common imperial foreign policy formulated by a process of “continuous consultation.” It worked well enough at the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference of 1921-22, but only because Britain accepted the Canadian view and terminated the Anglo-Japanese Alliance against the advice of the Pacific dominions. The United States wanted the alliance ended, and Meighen placed good relations with the United States at the top of his priority list. But Washington marked an end, not a beginning.

For Mackenzie King domestic harmony, rather than imperial unity, was the main goal to be pursued in foreign and domestic affairs. His strategy was evident during his first term of office. In 1922 the revolutionary government of Turkey denounced the peace treaty signed by its predecessor and threatened to invade Greek-held territory, a place called Chanak in Asia Minor. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, appealed to Canada for assistance in enforcing the peace settlement. King was outraged because the appeal was made publicly. His reply was that he could make no commitment without the approval of Parliament, and that Parliament was in recess. In 1923 King further consolidated his position by insisting at an Imperial Conference that no resolutions were binding unless approved by each dominion parliament. After that there remained only legal details to be cleared up: a fisheries treaty with the United States was signed by Canada without British participation, and plans for a Canadian embassy in Washington were set afoot. In 1926 the Balfour Declaration described Britain and the dominions as equals in a Commonwealth partnership. The final constitutional definition came in the Statute of Westminster in 1931, when King was out of office. Canada’s control over its foreign and domestic policy was made complete, though a procedure to amend the British North America Act in Canada had still to be devised, and appeals of Supreme Court decisions to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain continued until 1949.

Most of this was mere icing on the cake of parliamentary sovereignty. The essence of King’s imperial and foreign policy was his rejection of prior commitments and his repeated insistence that “parliament will decide in the light of existing circumstances.” He believed that most Canadians were tired of foreign involvements. He

Knew, too, that foreign-policy issues divided Canadians deeply. A

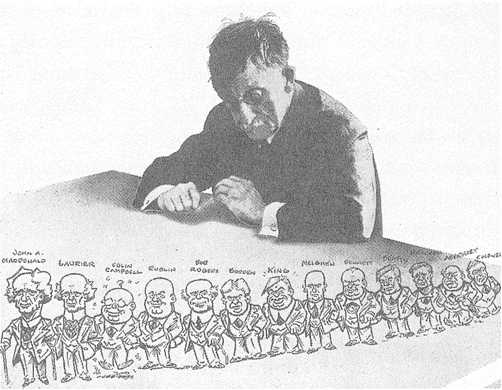

John W. Dafoe, editor of the Winnipeg Free Press from 1901 to 1944, chronicled the foibles, failings, and occasionally, successes of Canadian public leaders. Arch Dale, the paper’s brilliant cartoonist, created this composite for Dafoe’s sixtieth anniversary as a journalist.

Divided Canada meant a weakened Liberal party, perhaps even a repetition of the 1917 defeat. So he moved cautiously, but determinedly, towards a position of near isolation. Continuing to express his genuine attachment to the British Commonwealth, he manoeuvred Canada into a position of being able to decide alone and completely its obligations to that institution. While the result was hailed by nationalists in Canada, it had the effect of reducing the Commonwealth to virtual powerlessness as an instrument of collective security. That was what most Canadians, especially French Canadians, wanted. Ernest Lapointe, King’s powerful Quebec lieutenant, believed that this policy would ensure the Liberals unbroken success in his province.

In following the road to full Canadian autonomy within the Commonwealth, Mackenzie King had adopted the platform designed by Henri Bourassa two decades earlier. No wonder the nationalist movement in Quebec lapsed into near silence by the end of the 1920s. But, equally interesting, the King-Bourassa policy satisfied most English Canadians, too. There were occasional cries from Ontario Conservatives that King had betrayed the Empire, or from isolated internationalists, like John W. Dafoe of the Winnipeg Free Press, that withdrawal and isolation would not preserve world peace. But most Canadians preferred to believe that those who lived in fireproof houses had no need for insurance.

World History

World History