The Pequot War facilitated permanent English settlements in Connecticut and led to the rise of the Mohegan at the expense of the Pequot. It also temporarily unified the factious English despite challenges against Puritan orthodoxy presented by colonists like Anne Marbury Hutchinson during the Antinomian controversy. The conflict centered on the Dutch and English efforts to take advantage of the trade rivalry between the Narragansett and Pequot. These tribes dominated much of southern New England because they controlled the supply of wampum—valuable strings of beads produced from shells found mostly along the coast. Among Europeans the Dutch exercised the greatest influence in the region in the 1620s, with ties to both the Pequot and Narragansett. As parties of English splintered off from Massachusetts and expanded into the lower Connecticut River valley in the 1630s, the Dutch tried to solidify their claim to the region’s commerce by building a trading post and buying land. The Dutch could not, however, ease discontent within the tribes with whom they traded. Some of these communities had tributary relations with the Pequot and looked to the English as a way of severing these ties. Some signed separate trade agreements with the English or even ceded them land. Others, like the Narragansett, would, partially under the influence of English religious dissenter Roger Williams, ally with the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

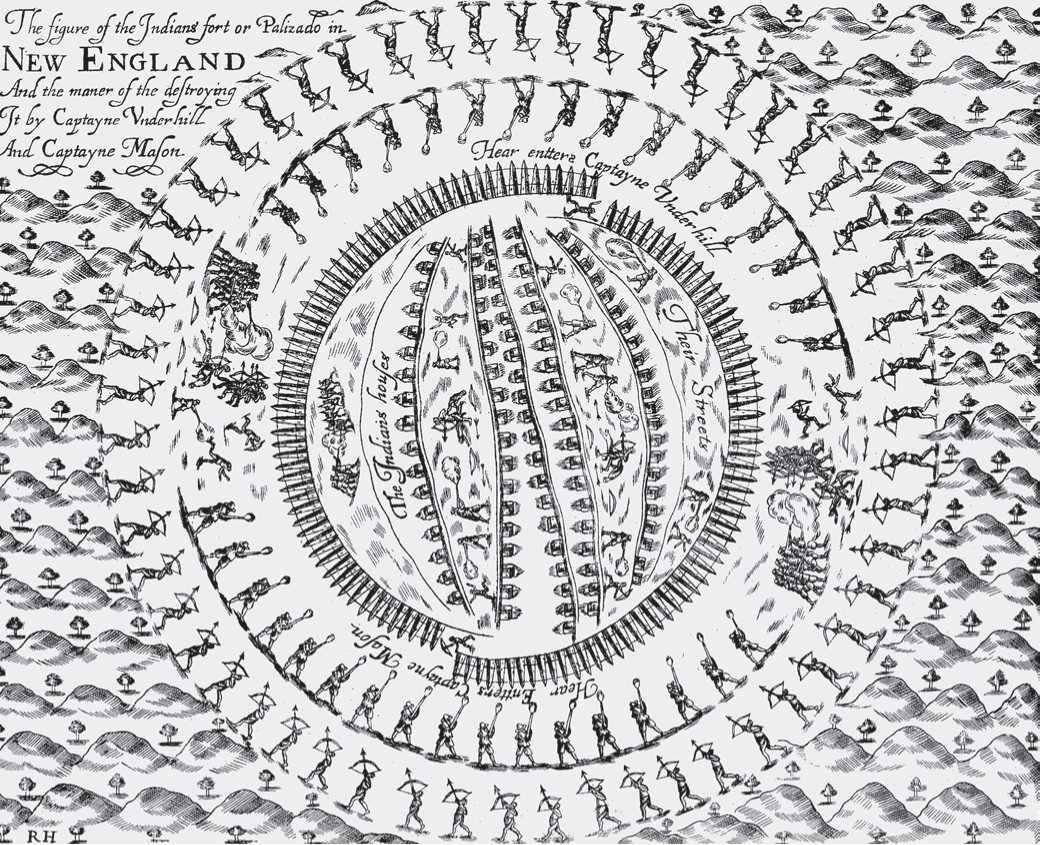

Hostilities arose because the English demanded that the Pequot hand over to Puritan justice the Indians whom they believed had killed Captain John Stone and some members of his crew. The English subsequently demanded that the Pequot pay hefty indemnities and provide hostages to guarantee that they would comply with the colonists’ desires. When the Pequot refused, the colonists sought vengeance. Together with their Narragansett and Mohegan allies, the English set out to subdue the Pequot, who, not coincidentally, occupied some of the most highly sought-after agricultural land in New England. Any hopes that the Pequot had of resisting were quashed in May 1637, when the English and their Indian allies attacked a palisaded Pequot village on the Mystic River. They surprised the village before dawn, and in the ensuing chaos the Puritans torched the village. As for those Pequot men, women, and children who managed to flee the flames, Englishmen, to the horror of their Indian allies, shot them down with their muskets. By the end of

This engraving depicts the Pequot encampment under attack by Captain John Mason and his men. (New York Public Library)

The day up to 700 Pequot had died. Most were noncombatants. Over the next several months the English captured many of the Pequot who were not at the scene. They executed some of the men and doled out most women and children to colonists or other Indians as servants. They even sold some Pequot into CARIBBEAN slavery. In the Treaty of Hartford (1638), which officially ended the war, the English declared the end of the Pequot nation.

The English and their Indian allies had contrasting views of the war and, particularly, the attack on Mystic River. The English, for the most part, saw the carnage as a sign of divine favor in their struggle against “savages.” The Indians, on the other hand, even if they had allied with the English, had never witnessed warfare of the scope or scale that waged by the English at the Pequot village. Their culturally prescribed rules of war had in the past dictated low-casualty conflicts characterized by hit and run tactics— often with the aim of acquiring live captives. The torching of the village and shooting of inhabitants as they fled prompted the Narragansett to complain about “the manner of the Englishmen’s fight. . . because it is too furious, and slays too many men.”

Although the Indians were shocked at the conduct of the Pequot War, some benefited from its results. Before the war Uncas’s Mohegan were linked to the Pequot by intermarriage and a tributary status. Uncas himself claimed to be the rightful leader by birth of both the Mohegan and Pequot. However, leadership of the Pequot was not entirely hereditary but stemmed partially from elections. In the first half of the 1630s, Uncas tried several times to depose the Pequot leader, Sassacus, only to fail repeatedly. When the English arrived looking to avenge John Stone’s death, Uncas found a power that could tilt the political balance in his favor. The aftermath of the Pequot defeat in 1637 saw Uncas’s emergence as the grand sachem of the Pequot and Mohegan. Uncas’s power coincided with the sharp rise of English power in Connecticut. The number of colonists living there increased sixfold in the six years after the war.

Further reading: Alfred A. Cave, The Pequot War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996).

—James D. Drake

World History

World History