GEOGRAPHY

Finland is bordered by Norway to the north, Sweden to the northwest, and Russia to the east. The Gulf of Bothnia makes up the western boundary and the Gulf of Finland is along the south coast. Aland, situated in the Baltic Sea, is an archipelago of about 6,500 islands belonging to Finland. Finland’s total area is 130,559 square miles, which includes more than 60,000 lakes, the largest of which are Saimaa, Inarijarvi, and Paijanne. Many canals and rivers (principally the Kemijoki and the Oulujoki) connect the lakes and rivers within Finland’s vast interior plateau. The landscape is mostly forests and woodland; only about 10 percent of the land (mostly along the coast) is used for agriculture. Northern Finland is known as Lapland (Saamiland), part of it is north of the Arctic Circle. Its terrain is marked by barren hills and some mountains. Finland’s highest peak, Haltiatun-turi (4,357 feet), is located near the Norwegian border.

INCEPTION AS A NATION

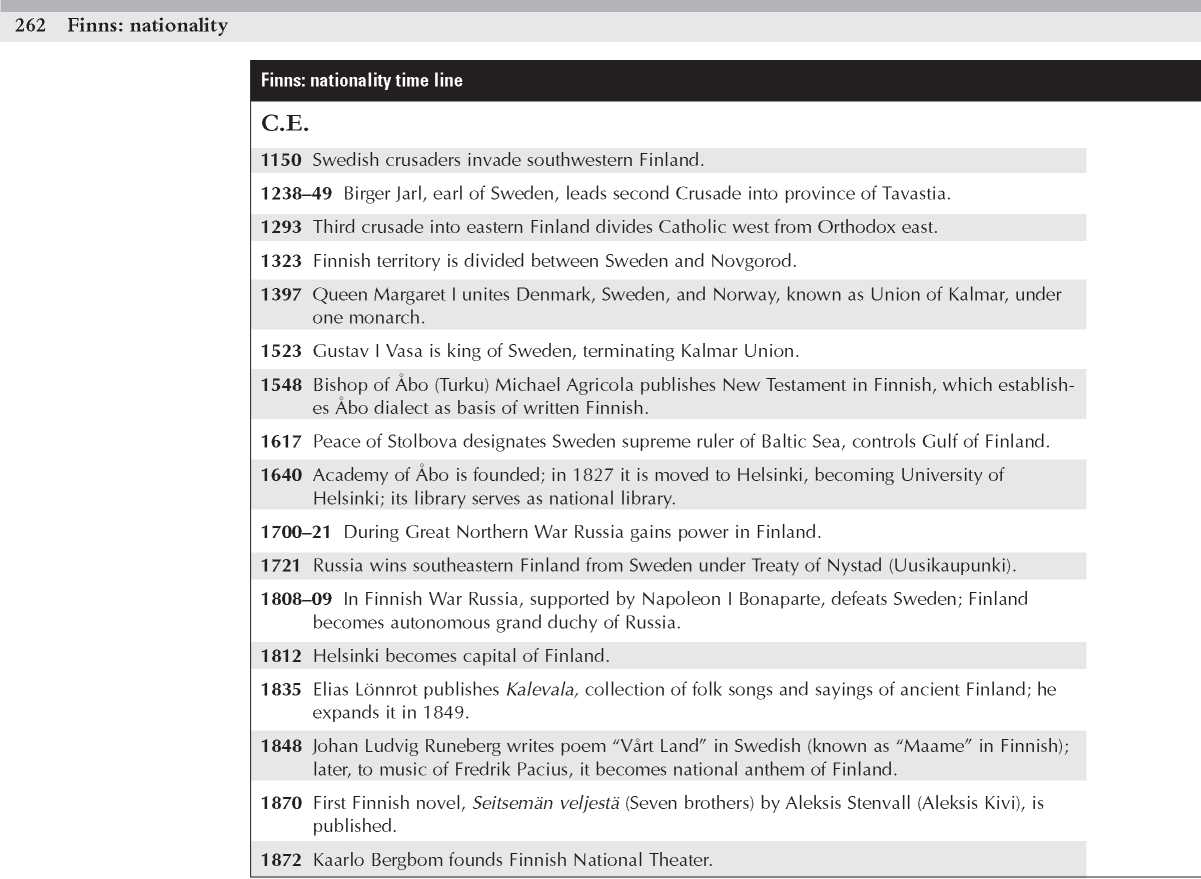

Christian crusaders traversed present-day Finland in the 12th century, attempting to convert tribal Finns. By the 1170s Sweden had invaded and settled the land. In the early 13th century the pope reaffirmed Swedish holdings in Finland, especially the eastern and northern territories. Birger Jarl of Sweden centralized Finland when forming Tavastia in 1249 as a defense against invading Russia. After Russian attacks a treaty of 1323 divided Karelia between Sweden and Novgorod.

Finland, a suzerainty of Sweden, was united with Norway, Denmark, and Sweden under the Union of Kalmar in 1397. It became a duchy of Sweden after a war with Russia in 1555-57. For the next quarter of a century Finland was one of the battlegrounds in the

FINNS: NATIONALITY nation:

Finland (Suomi, Suomen Tasavalta); Republic of Finland (Suomen Tasavalta)

Derivation of name:

Fennland, possibly a Germanic root meaning "wanderers"; Suomie, possibly from the Baltic root meaning "land"

Government:

Republic

Capital:

Helsinki

Language:

Finnish and Swedish are the official languages; Saami, a Finnic dialect, and Russian are also spoken.

Religion:

About 90 percent of the population belong to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland; small percentages are Orthodox Christians or atheists.

Earlier inhabitants:

Tribal Finns (Suomalaiset; Tavasts; Karelians; Kanulaiset; etc.); Saami

Demographics:

More than 90 percent of the population are Finnish; about 6 percent are Swedish; ethnic minorities include Saami, Russians, Rroma, and Tatars.

Conflict between Sweden and Russia. The Peace of Stolbova in 1617 ended war with Russia and extended Finnish boundaries eastward into Ingria. Throughout the 18th century conflict with Russia resulted in a loss of Finnish territory, notably during the Great Northern War (1700-21) when Russia acquired the province of Vyborg.

Russia, under a treaty with Napoleon I Bonaparte, attacked Finland, declaring it a Grand Duchy of Russia in 1809. By the Peace of Hamina Sweden officially gave Finland and Aland (archipelago) to Russia. In 1811 Finland regained the Karelian region and the province of Vyborg, territory previously ceded to Russia. Finland’s capital was moved from Turku to Helsinki the next year.

During the Russian Revolution of 1917 a newly elected parliament proclaimed Finland an independent republic. By an armistice of 1944 signed between Russia and Finland, Finland ceded the Petsamo region and leased the Porkkala Peninsula, which it did not reclaim until 1995.

CULTURAL IDENTITY

A driving force behind the emergence of a modern Finnish cultural identity has been the relations of Finns—those peoples descended from tribal Finno-Ugrians—to foreign occupying powers. The first of these was Sweden. Swedes and Finns have had close relations at least since the Swedish Vikings began trading Finnish products—importantly furs—south-ward through Russian territory in the sixth century C. E. Swedes, more “advanced” than Finns in terms of trends in western Europe, have usually dominated the latter, actually annexing Finnish territory in the 12th century. Thus modern Finns have developed their cultural identity in an atmosphere of struggle to remain independent and distinct.

In 1640 Sweden established the Turku (or Abo) Academy in Finland with the purpose of

1882 Martin Wegelius founds Helsinki Music Institute (now Sibelius Academy); Robert Kajanus founds Helsinki Orchestra Society (now Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra).

1899 Russian Czar Nicholas II implements February Manifesto, opposing Finnish constitution.

Jean Sibelius composes symphony Finlandia, inspired by nature and Finnish folktales; it is later banned by czarist authorities for its pro-Finnish themes.

1906 Finland declares national parliament; women are granted right to vote.

1917 During Russian Revolution Finland declares its independence.

1918 Civil war breaks out between Bolsheviks of southern Finland or Red Guards, and right-wing government of western Finland or White Guards; White Guards, supported by German troops, prevail.

1919 Finland becomes republic.

1920 Finland and Soviet Union (USSR) sign Peace of Tartu; Finland gains Petsamo area. Finland joins League of Nations.

1932 Finland and Soviet Union sign nonaggression pact.

1939 World War II begins; Winter War begins when Soviet Red Army invades Finland.

Novelist and short story writer Frans Eemil Sillanpaa wins Nobel Prize in literature.

1940 Winter War ends; under Peace of Moscow Finland cedes southeastern provinces to Soviet Union.

1944 As a result of Finnish and Soviet Union conflict along southern border agreement is signed in Moscow, restoring frontier of 1940; Soviet Union annexes Petsamo area.

1944-45 War begins in Lapland; Finland and Soviet Union sign Friendship Treaty.

1955 Finland joins United Nations (UN) and Nordic Council.

1992 Soviet Union nullifies Friendship Treaty.

1993 National Museum of Finland is founded in Helsinki; Finnish National Opera House, home of Finnish National Opera and Finnish National Ballet, is inaugurated in Helsinki.

1995 Finland joins European Union (EU).

2000 New constitution is adopted.

Drawing Finns into mainstream European culture. The assumption by the Swedish government that acquainting Finns with advanced cultural trends from wider Europe, filtered to them through a Swedish lens, would attach Finland even more closely to the Swedish Crown proved unfounded, as the intellectual tools Finns gained in the academy actually helped them promote a sense of cultural identity distinct from that of Swedes. Prior to this time most educated Finns spoke Swedish, which was the language of government and culture. But with the founding of the academy translations of important documents, such as law codes, into Finnish began. A rudimentary Latin-Swedish-Finnish dictionary was published in 1678. At the same time Finnish material, such as descriptions of ancient Finnish religion, began to be translated into Latin, making them available to scholars in other countries. One work included a Finnish folk song about the bear that became the first specimen of Finnish folk poetry known abroad. These efforts were the forerunners of the compilation in the 19 th century by Elias Lonnrot of oral Finnish epic poetry into the Kalevala.

Russia’s annexation of Finland from Sweden in 1809 at first opened the way to a resurgence of Finnish culture and language. The high point of this was the compilation of the Kalevala, whose great international literary importance has made Finnish oral poetic tradition central to Finnish cultural identity. The relative isolation of the Finnic peoples, living “on top of the world” in the arctic circumpolar region, has been partly responsible for the preservation of their oral poetry Peasants would sing this poetry to the accompaniment of the kantele, an instrument similar to a zither. The Kalevala was hailed as Finland’s national epic almost as soon as it appeared in 1835.

Later in the 19th century, however, Russia undertook efforts at “Russifying” Finland and imposing the Russian language. Finnish resistance marshalled international aid because of the fame of the Kalevala. The Finnish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair in 1900 assembled all the forces of the arts into a joint manifestation of Finland’s cultural identity, and the intelligentsia of Western Europe protested against Russian oppression.

The state of Finland established in 1917 did not comprise all Finnic speakers; a number of them living in Sweden and Norway and speaking what are usually considered dialects of the standard Finnish spoken in Finland— the Tornedalians and Kvens—believe that their languages are different enough from standard Finnish to be considered official minority languages and in recent decades have been campaigning to have them recognized as such. The Tornedalians have published much of their literature, including teaching materials for schools, fiction, newspaper articles, and translation of parts of the Bible, in what they call Meankieli (our language) in order to underscore its relationship with Tornedalian identity.

As is the case with many speakers of minority languages in Nordic countries, language has become a central component in the cultural identity of Finnic speakers outside Finland, aided by the fact that Finnish is not a Nordic or even an Indo-European language. There are many speakers of Finnish in Sweden (as well as Swedish speakers in Finland), the result of age-old movements back and forth, especially between northern Sweden and Finland, and they have become increasingly language conscious. There are a number of groups who moved from what is now Finland to Sweden. They include Middle Sweden’s “Forest Finns,” who have lived in Stockholm since the late Middle Ages, and the so-called Sweden Finns (or Swedish Finns), who moved to Sweden in the 20th century. All have lived under heavy pressure to assimilate, which has made preserving their language and culture difficult.

Finnish in Sweden has traditionally been stigmatized, its speakers assumed to be of low status. This attitude has gradually changed as many Sweden Finns learned to speak Swedish without an accent; in addition, they differ little in appearance from Swedes. Sweden Finns now can be found at every level of society, not just in blue-collar work. They have been able to preserve their own language because of the bilingualism movement in Sweden, which aims to give schoolchildren classes in both their native language (home language classes) and Swedish.

Traditional folk music sung and danced to the kantele continues to be popular in Finland. Pelimannimusiikki is a style of dance music. A school of Finnish symphonic music developed in the latter 19th century, its basic language and structure derived from German music, its thematic material from Finnish folk songs. The most celebrated exponent of this school was Jan Sibelius, whose stirring and majestic tone poem Finlandia is one of the most admired and beloved works of the international symphonic repertoire.

Finns continue to be fascinated by the shamanistic spiritual tradition of their ancestors. Shamanistic elements have long played an important role in poetry and song; a significant portion of the Kalevala consists of “charms”—incantations intended to gain aid for the singer from the spirit world. Many modern Finnish musicians derive inspiration from shamanistic drumming tradition, and other artists, playwrights, filmmakers, visual artists, use shamanic themes. The shaman as the seeker, who will go to great lengths and brave dangers to discover truth unmediated by language or other cultural filters, is an attractive figure to many modern Finns.

Further Reading

Thomas Kingston Derry. A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1979).

Max Jakobson. Finland in the New Europe (New York: Praeger, 1998).

Eino Jutikkala and Kauko Pirinen. A History of Finland, trans. Paul Sjoblom (Helsinki, Finland: Weilin & Goos, 1984).

George Maude. Historical Dictionary of Finland (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995).

Byron S. Nordstrom. Dictionary of Scandinavian History (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1986).

Fred Singleton and Anthony F. Upton. A Short History of Finland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Eric Solsten and Sandra W. Meditz, eds. Finland: A Country Study (Washington, D. C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1990).

Fir Manach See Monaig.

World History

World History