The most powerful woman in Byzantine history was the daughter of a bear trainer for the circus. Theodora (ca. 497-548) grew up in what her contemporaries regarded as an undignified and morally suspect atmosphere, and she worked as a dancer and burlesque actress, both dishonorable occupations in the Roman world. Despite her background, she caught the eye of Justinian, who was then a military leader and whose uncle (and adoptive father) Justin had himself risen from obscurity to become the emperor of the Byzantine Empire. Under Justinian’s influence, Justin changed the law to allow an actress who had left her disreputable life to marry whom she liked, and Justinian and Theodora married in 525. When Justinian was proclaimed coemperor with his uncle Justin on April 1, 527, Theodora received the rare title of augusta, empress. Thereafter her name was linked with Justinian’s in the exercise of imperial power.

Most of our knowledge of Theodora’s early life comes from the Secret History, a tell-all description of the vices of Justinian and his court, written by Procopius (proh-KOH-pee-uhs) (ca. 550), who was the official court historian and thus spent his days praising those same people. In the Secret History, he portrays Theodora and Justinian as demonic, greedy, and vicious, killing courtiers to steal their property. In scene after detailed scene, Procopius portrays Theodora as particularly evil, sexually insatiable, depraved, and cruel, a temptress who used sorcery to attract men, including the hapless Justinian.

In one of his official histories, The History of the Wars of Justinian, Procopius presents a very different Theodora. Riots between the supporters of two teams in chariot races — who formed associations somewhat like street gangs and somewhat like political parties — had turned deadly, and Justinian wavered in his handling of the perpetrators. Both sides turned against the emperor, besieging the palace while Justinian was inside it. Shouting N-I-K-A (victory), the rioters swept through the city, burning and looting, and destroyed half of Constantinople. Justinian’s counselors urged flight, but, according to Procopius, Theodora rose and declared:

For one who has reigned, it is intolerable to be an exile. . . . If you wish, O Emperor, to save yourself, there is no difficulty: we have ample funds and there are the ships. Yet reflect whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you will not prefer death to safety. I agree with an old saying that the purple [that is, the color worn only by emperors] is a fair winding sheet to be buried in.

Justinian rallied, had the rioters driven into the hippodrome, and ordered between thirty and thirty-five thousand men and women executed. The revolt was crushed and Justinian’s authority restored, an outcome approved by Procopius.

Other sources describe or suggest Theodora’s influence on imperial policy. Justinian passed a number of laws that improved the legal status of women, such as allowing women to own property the same way that men could and to be guardians over their own children. He forbade the abandonment of unwanted infants, which happened more often to girls than to boys, as boys were valued more highly. Theodora presided at impe rial receptions for Arab sheiks, Persian ambassadors, Germanic princesses from the West, and barbarian chieftains from southern Russia. When Justinian fell ill from the bubonic plague in 532, Theodora took over his duties, banning those who discussed his possible successor. Justinian is reputed to have consulted her every day about all aspects of state policy, including religious policy regarding the doctrinal disputes that continued throughout his reign. Theodora’s favored interpretation of Christian doctrine about the nature of Christ was not accepted by the main body of theologians in Constantinople—nor by Justinian — but she urged protection of her fellow believers and in one case hid an aged scholar in the women’s quarters of the palace for many years.

Theodora’s influence over her husband and her power in the Byzantine state continued until she died, perhaps of cancer, twenty years before Justinian. Her

Influence may have even continued after death, for Justinian continued to pass reforms favoring women and, at the end of his life, accepted her interpretation of Christian doctrine. Institutions that she established, including hospitals, orphanages, houses for the rehabilitation of prostitutes, and churches, continued to be reminders of her charity and piety.

Theodora has been viewed as a symbol of the manipulation of beauty and cleverness to attain position and power, and also as a strong and capable co-ruler who held the empire together during riots, revolts, and deadly epidemics. Just as Procopius expressed both

Views, the debate continues today among writers of science fiction and fantasy as well as biographers and historians.

Questions for Analysis

1. How would you assess the complex legacy of Theodora?

2. Since the public and private views of Procopius are so different regarding the empress, should he be trusted at all as a historical source?

Much as we use the terms the college or the university when referring to academic administrators.

In early Christian communities the local people elected their leaders, or bishops. Bishops were responsible for the community’s goods and oversaw the distribution of those goods to the poor. They also were responsible for maintaining orthodox (established or correct) doctrine within the community and for preaching. Bishops alone could confirm believers in their faith and ordain men as priests.

The early Christian church benefited from the brilliant administrative abilities of some bishops. Bishop Ambrose, for example, the son of the Roman prefect of Gaul, was a trained lawyer and the governor of a province. He is typical of the Roman aristocrats who held high public office, were converted to Christianity, and subsequently became bishops. Such men later provided social continuity from Roman to Germanic rule. As bishop of Milan, Ambrose himself exercised responsibility in both the business and church affairs of northern Italy.

During the reign of Diocletian (284-305), the Roman Empire had been divided for administrative purposes into geographical units called dioceses. Gradually the church made use of this organizational structure. Christian bishops established their headquarters, or sees, in the urban centers of the old Roman dioceses. A bishop’s jurisdiction extended throughout the diocese. The center of his authority was his cathedral (from the Latin cathedra, meaning "chair”). Thus, church leaders adapted the Roman imperial method of organization for ecclesiastical purposes.

The bishops of Rome-known as "popes,” from the Latin word papa, meaning "father”—claimed to speak and act as the source of unity for all Christians. They based their claim to be the successors of Saint Peter and heirs to his authority as chief of the apostles on Jesus’ words:

You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the jaws of death shall not prevail against it. I will entrust to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you declare bound on earth shall be bound in heaven; whatever you declare loosed on earth shall be loosed in heaven.1

Petrine Doctrine The statement used by popes, bishops of Rome, based on Jesus’ words, to substantiate their claim

Of being the successors of Saint Peter and heirs to his authority as chief of the apostles.

Theologians call this statement the Petrine (PEE-tryne) Doctrine.

After the capital and the emperor moved from Rome to Constantinople (see page 128), the bishop of Rome exercised considerable influence in the West because he had no real competitor there. He became known as the "Patriarch of the West.” In the East, the bishops of Antioch, Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, because of the special dignity of their sees, also gained the title of patriarch. Their jurisdictions extended over lands adjoining their sees; they consecrated bishops, investigated heresy, and heard judicial appeals.

In the fifth century the bishops of Rome began to stress their supremacy over other Christian communities and to urge other churches to appeal to Rome for the resolution of disputed doctrinal issues. While local churches often exercised their own authority and Rome was not yet as powerful as it would become, these arguments laid the groundwork for later appeals.

The Church and the Roman Emperors

The church benefited considerably from the emperors’ support. Constantine had legalized the practice of Chris t ianity in the empire in 312 and encouraged it throughout his reign. He freed the clergy from imperial taxation. At churchmen’s request, he helped settle theological disputes and thus preserved doctrinal unity within the church. Constantine generously endowed the building of Christ ian

Churches, and one of his gifts —the Lateran (LAT-er-uhn) Palace in Rome-remained the official residence of the popes until the fourteenth century. Constantine also declared Sunday a public holiday, a day of rest for the service of God. Because of its favored position in the empire, Christianity slowly became the leading religion (see Map 7.2).

Arianism A theological belief that originated with Arius, a priest of Alexandria, denying that Christ was divine and co-eternal with God the Father.

I heresy The denial of a basic doctrine I of faith.

In the fourth century, theological disputes frequently and sharply divided the Christian community. Some disagreements had to do with the nature of Christ. For example, Arianism (AIR-ree-uh-nizm), which originated with Arius (ca. 250336), a priest of Alexandria, held that Jesus was created by the will of the Father and thus was not co-eternal with the Father. Arius also reasoned that Jesus the Son must be inferior to God the Father because the Father was incapable of suffering and did not die. Orthodox theologians branded Arius’s position a heresy—the denial of a basic doctrine of faith.

Arianism enjoyed such popularity and provoked such controversy that Constantine, to whom religious disagreement meant civil disorder, interceded. He summoned church leaders to a council in Nicaea (neye-SEE-uh) in Asia Minor and presided over it personally. The council produced the Nicene (neye-SEEN) Creed, which defined the orthodox position that Christ is "eternally begotten of

MAP 7.2 The Spread of Christianity

Originating in Judaea, the southern part of modern Israel and Jordan, Christianity first spread throughout the Roman world and then beyond it in all directions.

The Father” and of the same substance as the Father. Arius and those who refused to accept the creed were banished, the first case of civil punishment for heresy. This participation of the emperor in a theological dispute within the church paved the way for later emperors to do the same.

In 380 the emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the empire. Theodosius stripped Roman pagan temples of statues, made the practice of the old Roman state religion a treasonable offense, and persecuted Christians who dissented from orthodox doctrine. Most significant, he allowed the church to establish its own courts and to use its own body of law, called "canon law.” These courts, not the Roman government, had jurisdiction over the clergy and ecclesiastical disputes. At the death of Theodosius, the Christian church was considerably independent of the Roman state. The foundation for later growth in church power had been laid.

Orthodox church Eastern orthodox church in the Byzantine empire.

Later Byzantine emperors continued the pattern of active involvement in church affairs. They appointed the highest officials of the church hierarchy and presided over ecumenical councils, where bishops would gather to make decisions on matters of faith and practice. The emperors also controlled some of the material resources of the church-land, rents, and indebted peasants. On the other hand, the emperors had minimal involvement in church services and rarely tried to impose their views in theological disputes. Greek churchmen vigorously defended the church’s independence; some even asserted the superiority of the bishop’s authority over the emperor’s; and the church possessed such enormous economic wealth and influence over the population that it could block government decisions. The Orthodox church, the name generally given to the Eastern Christian church, was less independent of secular control than the Western Christian church, but it was not simply a branch of the Byzantine state.

The Development of Christian Monasticism

Christianity began and spread as a city religion. Since the first century, however, some especially pious Christians had felt that the only alternative to the decadence of urban life was complete separation from the world. All-consuming pursuit of material things, sexual promiscuity, and general political corruption disgusted them. They believed that the Christian life as set forth in the Gospel could not be lived in the midst of such immorality. They rejected the values of Roman society and were the first real nonconformists in the church.

Eremitical A form of monasticism that began in Egypt in the third century where individuals and small groups withdrew from cities and organized society to seek God through prayer. The people who lived in caves and sought shelter in the desert and mountains were called hermits, from the Greek word eremos.

This desire to withdraw from ordinary life led to the development of the monastic life. Some scholars believe that the monastic life of extreme material sacrifice appealed to Christ ians who wanted to make a total response to Christ’s teachings; the monks became the new martyrs. Saint Anthony of Egypt (251?-356), the earliest monk for whom there is concrete evidence and the man later considered the father of monasticism, went to Alexandria during the persecutions of the Emperor Diocletian in the hope of gaining martyrdom. Christians believed that monks like the martyrs before them, could speak to God and that their prayers had special influence.

Monasticism began in Egypt in the third century. At first individuals and small groups withdrew from cities and from organized society to seek God through prayer in desert or mountain caves and shelters. Gradually large colonies of monks gathered in the deserts of Upper Egypt. These monks were called hermits, from the Greek word eremos, meaning "desert.” Many devout women also were attracted to this eremitical (er-uh-MIT-ik-ul) type of monasticism.

The Egyptian ascetic Pachomius (puh-KOH-mee-uhs) (290-346?) drew thousands of men and women to the monastic life at Tabennisi on the Upper Nile. There were too many for them to live as hermits, and Pachomius organized communities of men and women, creating a second type of monasticism, known as coenobitic (seh-nuh-BIT-ik) (communal). Saint Basil (329?-379), the scholarly bishop from Asia Minor, encouraged coenobitic monasticism, as he and the church hierarchy thought that communal living provided an environment for training the aspirant in the virtues of charity, poverty, and freedom from self-deception.

Western and Eastern Monasticism

Coenobitic monasticism Communal

Living in monasteries, encouraged by Saint Basil and the church because it provided an environment for training the aspirant in the virtues of charity, poverty, and freedom from self-deception.

In the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries, information about Egyp tian monasticism came to the West, and both men and women sought the monastic life. Because of the difficulties and dangers of living alone in the forests of northern Europe, the eremitical form of monasticism did not take root. Most of the monasticism that developed in Gaul, Italy, Spain, England, and Ireland was coenobitic.

Regular clergy Men and women who lived in monastic houses and followed sets of rules, first those of Benedict and later those written by other individuals.

Secular clergy Priests and bishops who staffed churches where people worshiped and were not cut off from the world.

In 529 Benedict of Nursia (480-543), who had experimented with both the eremitical and the communal forms of monastic life, wrote a brief set of regulations for the monks who had gathered around him at Monte Cassino between Rome and Naples. Benedict’s guide for monastic life, known as the Rule of Saint Benedict, slowly replaced all others. The Rule of Saint Benedict came to influence all forms of organized religious life in the Roman church. Men and women who lived in monastic houses all followed sets of rules, first those of Benedict and later those written by other individuals, and because of this came to be called regular clergy, from the Latin word regulus (rule). Priests and bishops who staffed churches in which people worshiped and who were not cut off from the world were called secular clergy. (According to official church doctrine, women are not members of the clergy, but this distinction was not clear to most medieval people.)

The Rule of Saint Benedict offered a simple code for ordinary men. It outlined a monastic life of regularity, discipline, and moderation in an atmosphere of silence. Each monk had ample food and adequate sleep. The monk spent part of each day in formal prayer, which Benedict called the Opus Dei (Work of God) and Christians later termed the divine office, the public prayer of the church. This consisted of chanting psalms and other prayers from the Bible in the part of the monastery church called the "choir.” The rest of the day was passed in manual labor, study, and private prayer.

Why did the Benedictine form of monasticism eventually replace other forms of Western monasticism? The monastic life as conceived by Saint Benedict struck a balance between asceticism and activity. It thus provided opportunities for men of entirely different abilities and talents—from mechanics to gardeners to literary scholars. The Benedictine form of religious life also proved congenial to women. Five miles from Monte Cassino at Plombariola, Benedict’s twin sister Scholastica (skoh-LAS-tih-kuh) (480-543) adapted the Rule for use by her community of nuns.

Benedictine monasticism also succeeded partly because it was so materially successful. In the seventh and eighth centuries monasteries pushed back forests and wastelands, drained swamps, and experimented with crop rotation. Benedictine houses made a significant contribution to the agricultural development of Europe. The communal nature of their organization, whereby property was held in common and profits were pooled and reinvested, made this contribution possible.

Finally, monasteries conducted schools for local young people. Some students learned about prescriptions and herbal remedies and went on to provide medical

Section Review

Early Christian communities elected their leaders, or bishops, who oversaw the doctrine, preaching, and other community functions of their jurisdiction (diocese).

The bishops of Rome, known as “popes,” exercised more and more power, claiming to speak and act as the unitary source of authority for all Christians, while enjoying the benefits of the emperor's support.

Constantine set up and presided over the council of Nicaea, producing the Nicene Creed, which declared Jesus to be divine and settled a dispute between two Christian factions by banishing anyone who refused to accept it.

Those who wanted to separate themselves from perceived corruption in society chose one of the two monastic lifestyles: eremitical (isolated) or coenobitic (communal).

The monk Benedict of Nursia wrote a set of regulations for monks that became favored for both monks (men) and nuns (women) because of its balance between asceticism and activity.

Monasteries were successful in both the East and West but only the Western monasteries provided schools with educational training for local young people.

Treatment in their localities. A few copied manuscripts and wrote books. Local and royal governments drew on the services of the literate men and able administrators the monasteries produced. This was not what Saint Benedict had intended, but perhaps the effectiveness of the institution he designed made it inevitable.

Monasticism in the Greek Orthodox world differed in fundamental ways from the monasticism that evolved in western Europe. First, while The Rule of Saint Benedict gradually became the universal guide for all western European monasteries, each individual house in the Byzantine world developed its own set of rules for organizat ion and behavior, including rules about diet, clothing, liturgical functions, commemorative services for benefactors, the training of monks and nuns, and the election of officials. Second, education never became a central feature of the Greek houses. Monks and nuns had to be literate to perform the services of the choir, but no monastery assumed responsibility for the general training of the local young.

There were also similarities between Western and Eastern monasticism. As in the West, Eastern monasteries became wealthy, with fields, pastures, livestock, and buildings. Since bishops and patriarchs of the Greek church were recruited only from the monasteries, Greek houses also exercised cultural influence.

How did Christian thinkers adapt Greco-Roman ideas to Christian theology?

The evolution of Christianity was not simply a matter of institutions such as the papacy and monasteries, but also of ideas. Initially, Christians had believed that the end of the world was near and that they should dissociate themselves from the “filth” of Roman culture. The church father Tertullian (ter-TUHL-ee-uhn) (ca. 160-220) claimed: “We have no need for curiosity since Jesus Christ, nor for inquiry since the gospel.” Gradually, however, Chris tians developed a culture of ideas that drew upon classical influences. The distinguished theologian Saint Jerome (340-419) translated the Old and New Testaments from Hebrew and Greek into vernacular Latin; his edition is known as the “Vulgate.” The synthesis of Greco-Roman and Christ ian ideas found greatest expression in the writings of Saint Augustine, whose work had a profound influence on Christian theology.

Chris tian attitudes toward gender and sexuality pro

Christian Notions of , , i i mr, r k m

Vide a good example of the ways early Christians both

Gender and Sexuality a, a n n r n rk crk

Adopted and adapted the views of their contemporary world. In his plan of salvation, Jesus considered women the equal of men. He attributed no disreputable qualities to women and did not refer to them as inferior creatures. On the contrary, women were among his earliest and most faithful converts. He discussed his mission with them (John 4:21-25), and the first persons to whom he revealed himself after his resurrection were women (Matthew 28:9-10).

Women took an active role in the spread of Christianity, preaching, acting as missionaries, being martyred alongside men, and perhaps even baptizing believers. Because early Christians believed that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, they devoted their energies to their new spiritual family of co-believers. Early Christians often met in people’s homes and called one another brother and sister, a metaphorical use of family terms that was new to the Roman Empire.

Saint Augustine on Human Nature, Will, and Sin

The Marys at Jesus’ Tomb

This late-fourth-century ivory panel tells the story of Mary Magdalene and another Mary who went to Jesus' tomb to anoint the body (Matthew 28:1-7). At the top, guards collapse when an angel descends from Heaven, and at the bottom, the Marys listen to the angel telling them that Jesus had risen. Immediately after this, according to Matthew's Gospel, Jesus appears to the women. Here the artist uses Roman artistic styles to convey Christian subject matter, an example of the assimilation of classical form and Christian teaching. (Castello Sforzesco/Scala/Art Resource, NY)

Some women embraced the ideal of virginity and either singly or in monastic communities declared themselves "virgins in the service of Christ.” All this made Christianity seem dangerous to many Romans, especially when becoming Chris tian actually led some young people to avoid marriage, which was viewed by Romans as the foundation of society and the proper patriarchal order.

Not all Christian teachings about gender were radical, however. In the first century c. e. male church leaders began to place restrictions on female believers. Paul and later writers forbade women to preach, and women were gradually excluded from holding official positions in Christianity other than in women’s monasteries. In so limiting the activities of female believers Christianity was following classical Mediterranean culture, just as it patterned its official hierarchy after that of the Roman Empire.

Christian teachings about sexuality also built on classical culture. Many early church leaders, who are often called the church fathers, renounced marriage and sought to live chaste lives not only because they expected the Second Coming imminently, but also because they accepted the hostility toward the body that derived from certain strains of Hellenistic philosophy. Just as spirit was superior to matter, the mind was superior to the body. Though God had clearly sanctioned marriage, celibacy was the highest good. This emphasis on self-denial led to a strong streak of misogyny (hatred of women) in their writings, for they saw women and female sexuality as the chief obstacles to their preferred existence. They also saw intercourse as little more than animal lust, the triumph of the inferior body over the superior mind. Same-sex relations — which were generally acceptable in the Greco-Roman world, especially if they were between socially unequal individuals—were evil. The church fathers’ misogyny and hostility toward sexuality had a greater influence on the formation of later attitudes than did the relatively egalitarian actions and words of Jesus.

The most influential church father in the West was Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). Saint Augustine was born into an urban family in what is now Algeria in North Africa. His father, a minor civil servant, was a pagan; his mother, Monica, a devout Christian. It was not until adulthood that he converted to his mother’s religion. As bishop of the city of Hippo Regius, he was a renowned preacher, a vigorous defender of orthodox Christ ianity, and the author of more than ninety-three books and treatises.

Augustine’s autobiography, The Confessions, is a literary masterpiece. Written in the rhetorical style and language of late Roman antiquity, it marks the synthesis of Greco-Roman forms and Christian thought. The Confessions describes Augustine’s moral struggle, the conflict between his spiritual aspirations and his sensual self. Many Greek and Roman philosophers had taught that knowledge and virtue are the same: a person who knows what is right will do what is right. Augustine rejected this idea. People do not always act on the basis of rational knowledge.

Sacraments Certain rituals defined by the church in which God bestows benefits on the believer through grace.

Section Review

Christians at first thought the end of the world was near so they should separate themselves from Roman culture, but gradually they developed a culture of ideas that included classical influences.

Initially, both men and women played important roles, with women preaching and acting as missionaries, but in the first century C. E. male leaders, following classical culture, began to restrict women's participation in official positions.

Christian teachings on sexuality also adopted ideas from certain strains of Hellenistic philosophy, prescribing celibacy and self-denial as the highest good, leading to misogyny and hostility toward women and same-sex relations.

Augustine's ideas about sin (the result of will) and grace (the result of God, not humans) became the foundation for Western Christian theology.

Augustine argued in his work City of God that the state is the result of people's will to sin and that the church is responsible for the salvation of all, leading to the church's political view that it was superior to secular authority.

I

For example, Augustine regarded a life of chastity as the best possible life even before he became a Christian. As he notes in The Confessions, as a young man he prayed to God for "chastity and continency” and added "but not yet.” His education had not made his will strong enough to avoid temptation; that would come only through God’s power and grace.

Augustine’s ideas on sin, grace, and redemption became the foundation of all subsequent Western Christian theology, Protestant as well as Catholic. He wrote that the basic or dynamic force in any individual is the will. When Adam ate the fruit forbidden by God in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:6), he committed the "original sin” and corrupted the will. Adam’s sin was not simply his own, but was passed on to all later humans through sexual intercourse; even infants were tainted. Augustine viewed sexual desire as the result of Adam and Eve’s disobedience, linking sexuality even more clearly with sin than had earlier church fathers. Because Adam disobeyed God, all human beings have an innate tendency to sin: their will is weak. But according to Augustine, God restores the strength of the will through grace, which is transmitted in certain rituals that the church defined as sacraments. Grace results from God’s decisions, not from any merit on the part of the individual.

When the Visigothic (viz-ee-GOTH-ic) chieftain Alaric (AL-er-ik) conquered Rome in 410, horrified pagans blamed the disaster on the Christians. In response, Augustine wrote City of God. This original work contrasts Christianity with the secular society in which it existed. According to Augustine, history is the account of God acting in time. Human history reveals that there are two kinds of people: those who live the life of the flesh in the City of Babylon and those who live the life of the spirit in the City of God. The former will endure eternal hellfire; the latter will enjoy eternal bliss.

Augustine maintained that states came into existence as the result of people’s inclination to sin. The state provides the peace, justice, and order that Christians need in order to pursue their pilgrimage to the City of God. The church, while not the equivalent of the City of God, is responsible for the salvation of all-including Christian rulers. Churches later used Augustine’s theory to argue their superiority over secular authority. This remained the dominant political theory until the late thirteenth century.

Christian Missionaries and Conversion

What techniques did missionaries develop to convert barbarian peoples to Christianity?

The word catholic derives from a Greek word meaning "general,” "universal,” or "worldwide.” Christ had said that his teaching was for all peoples, and Christians sought to make their faith catholic-that is, believed everywhere. This could be accomplished only through missionary activity. As Saint Paul had written to the Christian community at Colossae (kuh-LOS-ee) in Asia Minor, "there is no room for distinction between Greek and Jew, between the circumcised or the uncircumcised, or between barbarian or Scythian (SITH-ee-uhn), slave and free man. There is only Christ; he is everything and he is in everything.”2 Paul urged Christians to bring the "good news” of Christ to all peoples. The Mediterranean served as the highway over which Christianity spread to the cities of the Roman Empire. From there missionaries took Christian teachings to the countryside, and then to areas beyond the borders of the empire.

Among the Germanic tribes of western Europe, religion was not a private or individual matter. It was a social affair, and the religion of the chieftain or king determined the religion of the people. Thus missionaries concentrated their initial efforts not on the people, but on kings or tribal chieftains. According to custom, kings negotiated with all foreign powers, including the gods. Because Chris tian missionaries represented a "foreign” power (the Chris tian God), the king dealt with them. Germanic kings accepted Christianity because they believed that the Christian God was more powerful than pagan gods and that the Christian God would deliver victory in battle, or because Christianity taught obedience to (kingly) authority, or because Christian priests possessed knowledge and a charisma that could be associated with kingly power. Kings who converted, such as Ethelbert of Kent and the Frankish chieftain Clovis (KLOH-vis), sometimes had Chris tian wives. Conversion may also have indicated that barbarian kings wanted to enjoy the cultural advantages that Christianity brought, such as literate assistants and an ideological basis for their rule.

Missionaries on the Continent

In eastern Europe, missionaries traveled far beyond the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire. In 863 the emperor Michael III sent the brothers Cyril (826-869) and Methodius (815-885) (muh-THOH-dee-uhs) to preach Christianity in Moravia (a region of the modern central Czech Republic). Other missionaries succeeded in converting the Russians in the tenth century. Cyril invented a Slavic alphabet using Greek characters; this script, called the "Cyrillic (sih-RIL-ik) alphabet,” is still in use today. Cyrillic script made possible the birth of Russian literature. Similarly, Byzantine art and architecture became the basis and inspiration of Russian forms. The Byzantines were so successful that the Russians claimed to be the successors of the Byzantine Empire. For a time Moscow was even known as the "Third Rome” (the second Rome being Constantinople).

Missionaries in The British Isles

Ardagh Silver Chalice

This chalice, crafted about 800 c. e. and used for wine in Christian ceremonies, formed part of the treasure of Ardagh Cathedral in County Limerick, Ireland. Made of several types of metal, it is decorated with Celtic patterns in the same way as Irish manuscripts from this era. Christianity was widespread in Ireland long before anywhere else in northern Europe, and Celtic traditions and practices differed significantly from those of Rome. (National Museum of Ireland)

Tradition identifies the conversion of the Celts of Ireland with Saint Patrick (ca. 385-461). After a vision urged him to Christianize Ireland, Patrick studied in Gaul and was consecrated a bishop in 432. He returned to Ireland, where he converted the Irish tribe by tribe, first baptizing the king. By the time of Patrick’s death, the majority of the Irish people had received Christian baptism. In his missionary work, Patrick had the strong support of Bridget of Kildare (kil-DAIR) (ca. 450-ca. 528), daughter of a wealthy chieftain. Bridget defied parental pressure to marry and became a nun. She and the other nuns at Kildare instructed relatives and friends in basic Christian doctrine, made religious vestments for churches, copied books, taught children, and above all set a religious example by their lives of prayer. In Ireland and later in continental Europe, women shared in the process of conversion.

The Christianization of the Engl ish began in 597, when Pope Gregory I (590-604) sent a delegation of monks under the Roman Augustine to Britain. Augustine’s approach, like Patrick’s, was to concentrate on converting the king. When he succeeded in converting Ethelbert, king of Kent, the baptism of Ethelbert’s people took place as a matter of course. Augustine established his headquarters, or see, at Canterbury, the capital of Kent.

In the course of the seventh century, two Christian forces competed for the conversion of the pagan Anglo-Saxons: Roman-oriented missionaries traveling north from Canterbury, and Celtic monks from Ireland and northwestern Britain. The Roman and Celtic church organization, types of monastic life, and methods of arriving at the date of the central feast of the Christian calendar (Easter) differed completely. Through the influence of King Oswiu of Northumbria (nawr-THUHM-bree-uh) and the energetic abbess Hilda of Whitby, the Synod (ecclesiastical council) held at Whitby in 664 opted to follow the Roman practices. The conversion of the English and the close attachment of the English church to Rome had far-reaching consequences because Britain later served as a base for the full-scale Christianization of the continent (see Map 7.2).

Conversion and Assimilation

Between the fifth and tenth centuries, the great majority of peoples living on the European continent and the nearby islands were baptized as Christians. When a ruler marched his people to the waters of baptism, though, the work of Christianization had only begun. Baptism meant either sprinkling the head or immersing the body in water. Conversion meant awareness and acceptance of the beliefs of Christianity, including those that seemed strange or radical, such as "love your enemies” or "do good to those that hate you.”

How did missionaries and priests get masses of pagan and illiterate peoples to understand and live by Christian ideals and teachings? They did so through preaching, assimilation, and the penitential system. Preaching aimed at presenting the basic teachings of Christ ianity and strengthening the newly baptized in their faith through stories about the lives of Christ and the saints. But deeply ingrained pagan customs and practices could not be stamped out by words alone or even by imperial edicts. Christian missionaries often pursued a policy of assimila-

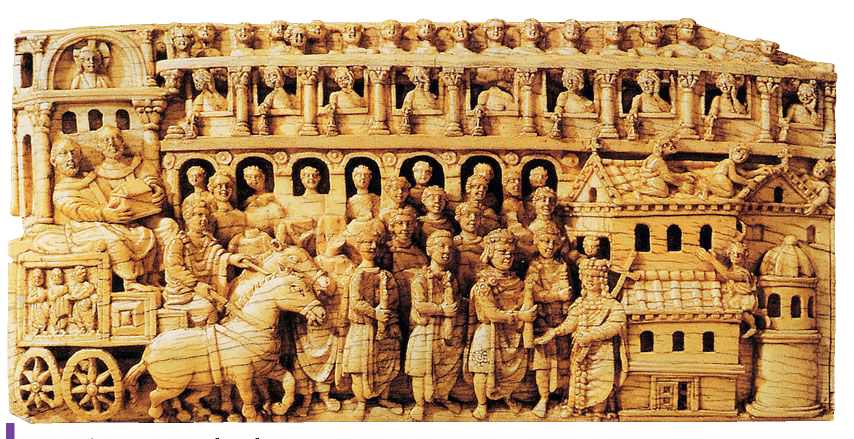

Procession to a New Church

In this sixth-century ivory carving, two men in a wagon, accompanied by a procession of people holding candles, carry a relic casket to a church under construction. Workers are putting tiles on the church roof. New churches often received holy items when they were dedicated, and processions were common ways in which people expressed community devotion. (Cathedral

Treasury, Trier. Photo: Ann Muenchow)

Tion, easing the conversion of pagan men and women by stressing similarities between their customs and beliefs and those of Chris tianity. In the same way that classically trained scholars such as Jerome and Augustine blended Greco-Roman and Christian ideas, missionaries and converts mixed pagan ideas and practices with Christian ones. Bogs and lakes sacred to Germanic gods became associated with saints, as did various aspects of ordinary life, such as traveling, planting crops, and worrying about a sick child. Aspects of existing midwinter celebrations, which often centered on the return of the sun as the days became longer, were incorporated into celebrations of Christmas. Spring rituals involving eggs and rabbits (both symbols of fertility) were added to Easter.

Also instrumental in converting pagans was the rite of reconciliation in which the sinner was able to receive God’s forgiveness. The penitent knelt individually before the priest, who questioned the penitent about the sins he or she might have committed. A penance such as fasting on bread and water for a period of time or saying specific prayers was imposed as medicine for the soul. The priest and penitent were guided by manuals known as penitentials (pen-uh-TENT-shuls), which included lists of sins and the appropriate penance. Penitentials gave pagans a sense of expected behavior. The penitential system also encouraged the private examination of conscience and offered relief from the burden of sinful deeds.

Most religious observances continued to be community matters, however, as they had been in the ancient world. People joined with family members, friends, and neighbors to celebrate baptisms and funerals, presided over by a priest. They prayed to saints or to the Virgin Mary to intercede with God, or they simply asked the saints for protection and blessing. The entire village participated in processions marking saints’ days or points in the agricultural year, often carrying images of saints or their relics—bones, articles of clothing, or other objects associated with the life of a saint—around the houses and fields.

What were some of the causes of the barbarian migrations and how did they affect the regions of Europe?

The migration of peoples from one area to another has been a dominant and continuing feature of Western history. Mass movements of Europeans occurred in the fourth through sixth centuries, in the ninth and tenth centuries, and in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. From the sixteenth century to the present, such movements have been almost continuous, involving not just the European continent but the entire world. The causes of early migrations varied and are not thoroughly understood by scholars. But there is no question that the migrations profoundly affected both the regions to which peoples moved and the ones they left behind.

In surveying the world around them, the ancient Greeks often conceptualized things in dichotomies, or sets of opposites: light/dark, hot/cold, wet/dry, mind/ body, male/female, and so on. One of their key dichotomies was Greek/non-Greek,

I penitentials Manuals for the I examination of conscience.

Relics Bones, articles of clothing, or other objects associated with the life of a saint.

Section Review

• St. Paul urged Christians to make their faith Catholic, meaning “universal” or “worldwide.”

• Christian missionaries spread their faith throughout the Roman Empire and beyond.

• In western Europe missionaries gained influence by converting leaders; in eastern Europe Christianity spread to Moravia and Russia, bringing with it the Cyrillic alphabet and inspiring Russian literature.

• Saint Patrick brought Christianity to Ireland while the nun Bridget of Kildare and other women worked to spread it there.

• Roman and Celtic church organization differed in types of monastic life and dates of the Christian calendar, but after an ecclesiastical council in 664, the British followed the Roman practices, tying the English church to Rome.

• Christian missionaries accomplished conversion of pagans by preaching and by assimilating existing pagan customs.

• The rite of reconciliation forgave individual sins through penance and confession to a priest, yet religion continued to be mostly a community matter.

Celts, Germans, and Huns

Barbarians A name given by the Romans to all peoples living outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire (except the Persians).

And the Greeks coined the word barbaros for those whose native language was not Greek, because they seemed to the Greeks to be speaking nonsense syllables—bar, bar, bar. ("Bar-bar” is the Greek equivalent to "blah-blah” or "yada-yada.”) Barbaros originally meant simply not speaking Greek, but gradually it also implied unruly, savage, and more primitive than the advanced civilization of Greece. The word brought this meaning with it when it came into Latin and other European languages, with the Romans referring to those who lived beyond the northeastern boundary of Roman territory as barbarians. Migrating groups that the Romans labeled as barbarians had pressed along the Rhine-Danube frontier of the Roman Empire since about 150 c. e. (see page 109). In the third and fourth centuries, increasing pressures on the frontiers from the east and north placed greater demands on Roman military manpower, which plague and a declining birthrate had reduced. Therefore, Roman generals recruited barbarian refugees and tribes allied with the Romans to serve in the Roman army, and some rose to the highest ranks.

As Julius Caesar advanced through Gaul between 58 and 50 b. c.e. (see page 102), the largest barbarian groups he encountered were Celts (whom the Romans called Gauls) and Germans. Modern historians have tended to use the terms German and Celt in a racial sense, but recent research stresses that Celt and German are linguistic terms, a Celt being a person who spoke a Celtic language, an ancestor of the modern Gaelic or Breton language, and a German one who spoke a Germanic language, an ancestor of modern German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, or Norwegian.

Celts and Germans were similar to one another in many ways. In the first century c. e., the Celts lived east of the Rhine River in an area bounded by the Main Valley and extending westward to the Somme (sawm) River. Germans were more numerous along the North and Baltic Seas. Both Germans and Celts used wheeled plows and a three-field system of crop rotation. Before the introduction of Christianity, both Celtic and Germanic peoples were polytheistic, with hundreds of gods and goddesses with specialized functions whose celebrations were often linked to points in the yearly agricultural cycle. Worship was often outdoors at sacred springs, groves, or lakes.

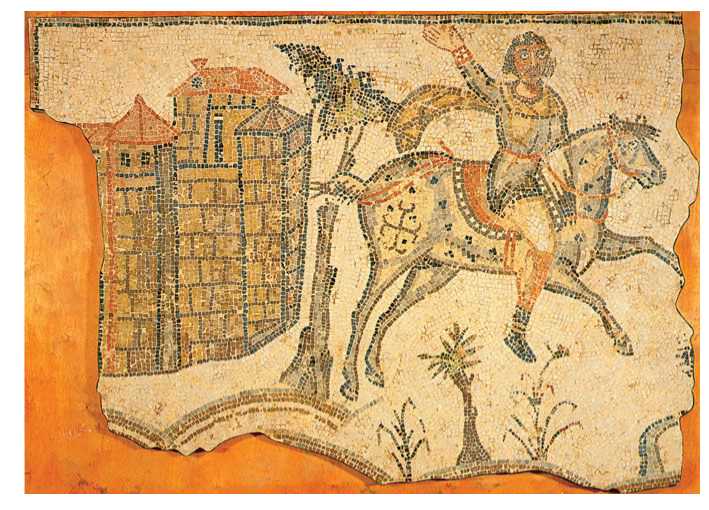

In this mosaic, a Vandal landowner rides out from his Roman-style house. His clothing-Roman short tunic, cloak, and sandals-reflects the way some Celtic and Germanic tribes accepted Roman lifestyles, though his beard is more typical of barbarian men's fashion.

(Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum)

The Celts had developed iron manufacturing, using shaft furnaces as sophisticated as those of the Romans to produce iron swords and spears. Celtic priests, called druids (DROO-idz), had legal and educational as well as religious functions, orally passing down laws and traditions from generation to generation. Bards singing poems and ballads also passed down stories of heroes and gods, which were written down much later. Celtic peoples conquered by the Romans often assimilated to Roman ways, adapting the Latin language and other aspects of Roman culture. By the fourth century c. e., under pressure from Germanic groups, the Celts had moved westward, settling in Brittany (modern northwestern France) and throughout the British Isles (Engl and, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland). The Picts of Scotland as well as the Welsh, Britons, and Irish were peoples of Celtic descent. (See Map 7.3.)

MAP 7.3 The Barbarian Migrations

This map shows the migrations of various barbarian groups in late antiquity and can be used to answer the following questions: [1] The map has no political boundaries. What does this suggest about the impact of barbarian migrations on political structures? [2] Human migration is caused by a combination of push factors (circumstances that lead people to leave a place) and pull factors (things that attract people to a new location). Based on the information in this and earlier chapters, what push and pull factors might have shaped the migration patterns you see on the map? [3] The movements of barbarian peoples used to be labeled “invasions" and are now usually described as “migrations." How do the dates on the map support the newer understanding of these movements?

The migrations of the Germanic peoples were important in the political and social transformations of late antiquity. Many modern scholars have tried to explain who the Germans were and why they migrated. The present consensus, based on the study of linguistic and archaeological evidence, is that there was not one but rather many Germanic peoples with very different cultural traditions. The largest Germanic tribe, the Goths, was a polyethnic group of about one hundred thousand people, including perhaps fifteen thousand to twenty thousand warriors. The tribe was supplemented by slaves, who, because of their desperate situation under Roman rule, joined the Goths during their migrations.3

Why did the Germans migrate? Like the Celts, in part they were pushed by groups living farther eastward, especially by the Huns from central Asia in the fourth and fifth centuries. In part, they were searching for more regular supplies of food, better farmland, and a warmer climate. Conflicts within and among Germanic groups also led to war and disruption, which motivated groups to move. Franks fought Alemanni (al-uh-MAN-ahy) in Gaul; Visigoths fought Vandals in the Iberian Peninsula and across North Africa; and Angles and Saxons fought Celtic-speaking Britons in England.

All these factors can be seen in the movement of the Visigoths, one of the Germanic tribes, from an area north of the Black Sea southeastward into the Roman Empire. Pressured by defeat in battle, starvation, and the movement of the Huns, the Visigoths petitioned the emperor Valens to admit them to the empire. Seeing in the hordes of warriors the solution to his manpower problem, Valens agreed. Once the Visigoths were inside the empire, Roman authorities exploited their hunger by forcing them to sell their own people as slaves in exchange for dog flesh: "the going rate was one dog for one Goth.” Still, the Visigoths sought peace. Fritigern offered himself as a friend and ally of Rome in exchange for the province of Thrace—land, crops, and livestock. Confident of victory over a considerably smaller army, Valens and his council chose to battle the Visigoths and lost.

Alaric I’s invasion of Italy and sack of Rome in 410 represents the culmination of hostility between the Visigoths and the Romans. The Goths burned and looted the city for three days, which caused many Romans to wonder whether God had deserted them. This led the imperial government to pull its troops from the British Isles and many areas north of the Alps, leaving these northern areas more vulnerable and open to migrating groups. A year later Alaric died, and his successor led his people into southwestern Gaul.4 Establishing their headquarters at Toulouse, they exercised a weak domination over Spain until a Muslim victory at Guadalete in 711 ended Visigothic rule.

One significant factor in Germanic migration was pressure from nomadic steppe peoples from central Asia. This included the Alans, Avars, Bulghars, Kha-zars, and most prominently the Huns, who attacked the Black Sea area and the Eastern Roman Empire beginning in the fourth century. Under the leadership of their warrior-king Attila, the Huns swept into central Europe in 451, attacking Roman settlements in the Balkans and Germanic settlements along the Danube and Rhine Rivers. After Attila turned his army southward and crossed the Alps into Italy, a papal delegation, including Pope Leo I himself, asked him not to attack Rome. Though papal diplomacy was later credited with stopping the advance of the Huns, a plague that spread among Hunnic troops and their dwindling food supplies were probably much more important. The Huns retreated from Italy, and within a year Attila was dead. Later leaders were not as effective, and the Huns were never again an important factor in European history. Their conquests had slowed down the movements of various Germanic groups, however, allowing barbarian peoples to absorb more of Roman culture as they picked the Western Roman Empire apart.

Between 450 and 565, the Germans established a Germanic Kingdoms Number of kingdoms, but none—other than the Frankish kingdom-lasted very long. The Germanic kingdoms did not have definite geographical boundaries, and their locations are approximate. The Vandals, whose destructive ways are commemorated in the word vandal, settled in North Africa. In northern and western Europe in the sixth century, the Burgundians (ber-GUHN-dee-uhns) ruled over lands roughly circumscribed by the old Roman army camps at Lyons, Besangon (buh-zahn-SAWN), Geneva, and Autun.

In northern Italy the Ostrogothic king Theodoric (r. 471-526) established his residence at Ravenna and gradually won control of all Italy, Sicily, and the territory north and east of the upper Adriatic. Although attached to the customs of his people, Theodoric pursued a policy of assimilation between Germans and Romans. He maintained close relations with the emperor at Constantinople and attracted able scholars such as Cassiodorus (kas-ee-uh-DAWR-uhs) (see page 212) to his administration. Theodoric’s accomplishments were significant, but his administration fell apart after his death.

Salic Law A law code issued by Salian Franks that provides us with the earliest description of Germanic customs.

Merovingian The Frankish dynasty named after its founder, Merowig, a man of mythical origins.

The kingdom established by the Franks in the sixth century, in spite of later civil wars, proved to be the most powerful and enduring of all the Germanic kingdoms. In the fourth and fifth centuries, they settled within the empire and allied with the Romans, some attaining high military and civil positions. In the sixth century one group, the Salian (SAY-lee-uhn) Franks, issued a law code called the Salic (SAL-ik) Law, the earliest description of Germanic customs. Chlodio (fifth century) is the first member of the Frankish dynasty for whom evidence survives. According to legend, Chlodio’s wife went swimming, encountered a sea monster, and conceived Merowig. The Franks believed that Merowig, a man of supernatural origins, founded their ruling dynasty, which was thus called Merovingian (mer-uh-VIN-jee-uhn).

The reign of Clovis (ca. 481-511) marks the decisive period in the development of the Franks as a unified people. Through military campaigns, Clovis acquired the central provinces of Roman Gaul. Clovis’s conversion to Christianity also brought him the crucial support of the papacy and of the bishops of Gaul. (See the feature "Listening to the Past: The Conversion of Clovis” on pages 160161.) The next two centuries witnessed the steady assimilation of Franks and Gallo-Romans, as many Franks adopted the Latin language and Roman ways, and Gallo-Romans copied Frankish customs and Frankish personal names. These centuries also saw Frankish acquisition of the Burgundian kingdom and of territory held by the Goths in Provence.5

The island of Britain was populated by various Celtic-Anglo-Saxon England Speaking tribes when it was conquered by Rome during the reign of Claudius. During the first four centuries c. e., it shared fully in the life of the Roman Empire. Towns were planned in the Roman fashion, with temples, public baths, theaters, and amphitheaters. In the countryside large manors controlled the surrounding lands. Roman merchants brought Eastern luxury goods and Eastern religions—including Christianity—into Britain. The Romans suppressed the Celtic chieftains, and a military aristocracy governed. In the course of the second and third centuries, many Celts assimilated to Roman culture, becoming Roman citizens and joining the Roman army.

When imperial troops withdrew from Britain in order to defend Rome from the Visigoths, the Picts from Scotland and the Scots from Ireland invaded British

Section Review

“Barbaras,” the Greek word that is the origin of “barbarian” originally meant not speaking Greek, but later implied savage and primitive.

Celts and Germans were similar in their polytheism and origins but the Celts moved westward under pressure from Germanic groups.

Germanic peoples migrated to search for better food and climate and because of conflicts with other groups, such as the Huns.

The longest-lasting of the Germanic kingdoms was the Frankish kingdom under Clovis, who settled within Roman Gaul and assimilated with the Gallo-Romans.

The Germanic Anglo-Saxons in Britain destroyed Roman culture as they fought among themselves and with the Britons to the west, before Viking invasions united them under King Alfred.

Celtic mythology and the legend of King Arthur may represent Celtic hostility toward Anglo-Saxon influence.

Celtic territory. According to the eighth-century historian Bede (beed) (see page 181), the Celtic king Vortigern invited the Saxons from Denmark to help him against his rivals in Britain. Saxons and other Germanic tribes from modern-day Norway, Sweden, and Denmark turned from assistance to conquest, attacking in a hit-and-run fashion. Their goal was plunder, and at first their invasions led to no permanent settlements. As more Germanic peoples arrived, however, they took over the best lands and eventually conquered most of Britain. Some Britons fled to Wales and the westernmost parts of England, north toward Scotland, and across the English Channel to Brittany. Others remained and eventually intermarried with Germanic peoples.

Historians have labeled the period 500 to 1066, the years of the Norman Conquest, as the “Anglo-Saxon” period, after the two largest Germanic tribes, the Angles and the Saxons. The Germanic tribes destroyed Roman culture in Britain. Christ ianity disappeared, large urban buildings were allowed to fall apart, and tribal custom superseded Roman law.

Anglo-Saxon England was divided along ethnic and political lines. The Germanic kingdoms in the south, east, and center were opposed by the Britons in the west, who wanted to get rid of the invaders. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms also fought among themselves, causing boundaries to shift constantly. Finally, in the ninth century, under pressure from the Viking invasions, the Celtic Britons and the Germanic Anglo-Saxons were molded together under the leadership of King Alfred of Wessex (WES-iks) (r. 871-899).

The Anglo-Saxon invasion gave rise to a rich body of Celtic mythology, particularly legends about the Celtic King Arthur, who first appeared in Welsh poetry in the sixth century and later in histories, epics, and saints’ lives. Most scholars see Arthur as a composite figure who evolved over the centuries in songs and stories. According to these texts, Arthur was the illegitimate son of the king of Britain whose royal parentage was revealed when he successfully drew the invincible sword Excalibur from a stone. Arthur won recognition as king and used Excalibur to win many battles. His quests included a search for the Holy Grail, the dish supposedly used by Jesus at the Last Supper, which was said to have miraculous powers. Arthur held his court at Camelot, where his knights were seated at the Round Table, where all were equal. Those knights included Sir Tristan, Sir Galahad, Sir Percival (Parsifal), and Sir Lancelot; Lancelot’s romance with Arthur’s wife Guinevere (GWIN-uh-veer) led to the end of the Arthurian kingdom. In their earliest form as Welsh poems, the Arthurian legends may represent Celtic hostility to Anglo-Saxon invaders, but they later came to be more important as representations of the ideal of medieval knightly chivalry and as great stories whose retelling has continued to the present.

What patterns of social, political, and economic life characterized barbarian society?

Germanic and Celtic society had originated in the northern parts of central and western Europe and the southern regions of Scandinavia during the Iron Age (800-500 b. c.e.). After Germanic kingdoms replaced the Roman Empire as the primary political structure throughout much of Europe, barbarian customs and traditions formed the basis of European society for centuries.

This eighth-century chest made of whalebone depicts warriors, other human figures, and a horse, with a border of runic letters. This chest tells a story in both pictures and words. The runes are one of the varieties from the British Isles, from a time and place in which the Latin alphabet was known as well. Runes and Latin letters were used side-by-side in some parts of northern Europe for centuries. (Erich tessing/Art Resource, NY)

Kinship, Custom, and Class

Runic alphabet Writings that help to give a more accurate picture of b

World History

World History