The First Cavalry Regiment during the Spanish-Ameri-CAN War, commanded by Theodore Roosevelt, was informally known as the Rough Riders and became famous for its charge up Kettle Hill during the Santiago campaign in Cuba. The volunteers who gathered at San Antonio for this mounted regiment were diverse and a bit exotic. Cowboys, bookkeepers, college boys, policemen, Indians, and Mexicans all signed up to fight Spain. Theodore Roosevelt, the future president but then the assistant secretary of the navy, resigned his post to join the unit. In an uncharacteristic act of humility he refused command because he felt unqualified, having only served three years with the New York National Guard. Roosevelt recommended his friend

Colonel Leonard Wood, an army surgeon and physician, to Secretary of War John Long. Roosevelt was made second in command. Unlike the rest of the army, the Rough Riders were outfitted with private funds provided by many of the soldiers themselves, thus assuring that they had the best equipment, such as Krag-Jorgenson rifles and smokeless powder cartridges.

Because of monumental confusion at the point of embarkation, the Rough Riders arrived at Daiquiri, Cuba, on June 22 without their horses. Forced to travel on foot, they distinguished themselves by their speed of advance. At the battle of Las Guasimas the swift-marching Rough Riders stormed and took Spanish entrenchments, thus opening up the road to Santiago before the infantry arrived.

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders atop the hill they captured, Battle of San Juan Hill, 1898 (Library of Congress)

On July 1 the Rough Riders, commanded by Roosevelt (Wood had moved up to command a brigade), would charge their way into history. The San Juan Heights was the key to taking Santiago, and on San Juan and Kettle Hills, the Spanish were in trenches and protected on their flanks by blockhouses. As the Americans attacked, they were pinned down by Spanish rifle fire with little protection other than tall jungle grass. In the ensuing confusion, regiments became mixed up. Roosevelt felt that they would all be killed if they remained in the grass, and finding himself the highest ranking officer, he ordered his Rough Riders and the other cavalry regiments to charge up Kettle Hill. When officers of the other regiments refused to do so without orders from their own commanding officers, Roosevelt told them to step aside and let his Rough Riders through. Roosevelt, riding one of the few horses to make it to Cuba, led his soldiers up the hill. The other regiments, fearing they would be seen as cowards, fell in with the Rough Riders. The farther the men advanced the faster they marched. The Spanish quickly retreated in the face of this mass of galloping, horseless cavalry. The Americans suffered many casualties taking the blockhouses, but by 1 p. M. Roosevelt and his men had taken Kettle Hill. Roosevelt paused for a few minutes and then joined in the successful charge up San Juan Hill.

At the end of the war the First Volunteer Cavalry unit was disbanded. Roosevelt returned home to a hero’s welcome, was soon elected governor of New York, and would in a few years be president of the United States. And yet he knew that July 1, 1898, was “the great day of my life” and also realized that he would “talk about the regiment forever.”

Further reading: Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1979).

—Timothy E. Vislocky

Royce, Josiah (1855-1916) philosopher An idealist philosopher, Josiah Royce, whose parents were intrepid forty-niners, was born on November 20, 1855, in Grass Valley, California. Gold and prosperity eluded his family. With no adequate school in their mining town, his mother started one. Later, when the family moved to San Francisco, Royce attended Boys High School, excelled in mathematics, read widely in the Mercantile Library, and in 1871 entered the University of California at Berkeley. Although the university was only three years old, among Royce’s teachers were Joseph LeConte, a distinguished geologist and an advocate of the theory of EVOLUTION, and Edward Rowland Sill, an equally distinguished poet, who made Royce his undergraduate assistant. Royce also attracted the attention of university president Daniel CoiT Gilman, who left Berkeley in 1875, the year Royce graduated, to head the new Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Before leaving, Gilman, aware of Royce’s poverty, arranged loans that enabled him to study in Germany from 1875 to 1876, and Royce gratefully predicted it would “be the making of my whole life.”

Royce had taken the classical course of studies at Berkeley, and his graduate thesis was on the theology of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound, but at the German universities of Leipzig and Gottingen he studied philosophy and became “an idealist devoted. . . to pure learning for learning’s sake, . . . burning for a chance to help build the American University.” Gilman at Hopkins made that desire a possibility. In 1876 he appointed Royce one of 21 fellows at $500 a year, who while working on a Ph. D., could teach if they wished. For Royce, Hopkins was an incredible experience. In his first year he made lifelong friendships; experienced intellectual growth; enjoyed music, art, and the theater; taught a course on Schopenhauer’s philosophy; and gave five lectures on the “Return to Kant.” Typically, Royce did not simply repeat Schopenhauer but, while accepting his reality of tragedy, put a positive spin on Schopenhauer’s will and muted his pessimism. In Royce’s second year at Hopkins he cemented a lasting friendship with William James, who was visiting Hopkins and whom Royce had met in 1875. He encouraged Royce to pursue his dream of a career in philosophy. In 1878, at the age of 22, Royce was among the first four to receive a Hopkins Ph. D. His thesis, “Of the Interdependence of the Principles of Knowledge,” he later remarked, was “pure pragmatism.”

Since there were no jobs for a Ph. D. in philosophy and Royce had a strong background in literature, Gilman got him a job in 1878 teaching English literature at Berkeley. As much as he loved California’s scenery, Royce felt he was exiled. “There is no philosophy in California,” he complained to James, who addressed him as “the solitary philosopher between Bering’s Strait and Tierra del Fuego.” You are “lucky,” James told him, for opportunities are “only waiting for the disgrace of youth to fade from your person.” On October 2, 1880, Royce married Katherine Head, a linguist, poet, and pianist. They had three children.

In 1882 James arranged for Royce to substitute for him while he was on a one-year leave from Harvard. Royce stayed on at Harvard, where he and James remained close friends, despite strong philosophical differences. Royce was also supportive of Charles Sanders Peirce (like him, a superb logician), whom he appreciated but also disagreed with.

Royce’s philosophy evolved through the years. His parents were deeply religious, and Royce, after a youthful religious crisis, believed that scientific discoveries may undermine dogmas, but religious life endures; that beliefs are numerous, but the spirit of religion is one. That spirit underpinned his philosophical ideas. By 1885, when he published The Religious Aspect of Philosophy, he had moved away from the pragmatism of his Ph. D. thesis to “objective idealism” and ultimate truths (the Absolute). He proved this with logic rather than the “subjective idealism” felt by the transcendentalists. The Absolute became for Royce another name for God, and his book was hailed as a defense of theism. For Royce, the mind was compelled to believe in an absolute, while James believed the mind inclined to change and chance. Royce believed in monism, the oneness of things, while James believed in pluralism. Royce elaborated his views in the two-volume The World and the Individual (1899, 1901), based on lectures delivered at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Later, in The Problem of Christianity (2 vols., 1913) he substituted for the Absolute the “Universal Community” (the invisible true church) in which relationships can be redemptive. By the turn of the century Royce was renowned as America’s foremost philosopher and was the American leader of the idealistic school of philosophers. He inspired advanced students, but undergraduates found his lectures difficult to follow. His public lectures, which were to the point and supported moral and religious convictions, were successful.

Royce was generally aloof from politics, but he did not live in an ivory tower. He opposed racism, thought nationalism an evil, hated militarism, and deplored imperialism and war. He was deeply disturbed by World War I and, in keeping with his ideas, called for a worldwide community that “would promote interdependence, cooperation, and loyalty” to eternal ideals, and an international organization to preserve world peace. Despite his love of German culture, Royce condemned Germany as the “enemy of the human race.” He died on September 13, 1916.

Further reading: John Clendenning, The Life and Thought of Josiah Royce (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985).

Ryder, Albert Pinkham (1847-1917) painter Albert Pinkham Ryder was born on March 19, 1847, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. As a four-year-old child, he colored and drew and looked at old art magazines his older brother William brought him. His formal education ended with public grammar school, but his interest in art continued. New Bedford had an arts atmosphere. It was the home of Albert Bierstadt and several other successful artists. An amateur painter gave Ryder lessons in his studio, near a frame shop, where art exhibitions were organized and discussed. A whaling port, New Bedford offered an artist constant views of its harbor and beautiful country views within walking distance.

Around 1867 Ryder’s brother William, who had opened a restaurant in New York City and would later manage the Hotel Albert, moved his parents and three younger brothers to New York, where they all lived together. After Ryder was rejected by the National Academy of Design, he met William Edgar Marshall, a well-known portrait painter, who became his friendly critic and informal teacher and whom he later called “master.” Marshall had painted Ulysses S. Grant, Abraham Lincoln, and Henry Ward Beecher. When Ryder again applied to the National Academy of Design, he was accepted and studied there for four years, taking only drawing courses. Color and painting he learned from Marshall but refused to learn the technical aspects of painting from anyone. Throughout his career he was indifferent to them.

Even though he was shy, Ryder was popular in art school. Among his close friends was Helena de Kay. With her brother and husband, magazine editor Richard Watson Gilder, she promoted his early career. The Gilders in 1877 were among the founders of the Society of American Artists, for the next two decades the leading liberal art organization, which Ryder joined in time for its first exhibition. Around this time Ryder had an epiphany, when he was painting near his grandfather’s house on Cape Cod. While feeling discouraged by his inability to copy nature, he saw a view framed by two trees that “stood out like a painted canvas.” Ryder realized that art has a life of its own and that nature is just the departure point. “I squeezed out big chunks of pure, moist color and taking my palette knife, I laid on blue, green, white and brown in great sweeping strokes,” Ryder remembered. “I saw nature springing into life upon my dead canvas. It was better than nature, for it was vibrating with the thrill of a new creation.”

Ryder’s paintings of the 1870s are generally of horses or cows and sometimes people, either in a landscape or a stable, usually around sunset. He continued with landscapes throughout his career but in the 1880s started painting his famous moonlight marine paintings. Although he became entirely a studio artist, he would go to parks to observe trees and sky and on a trip to Europe was greatly interested in observing the effect of moonlight on water. While there, he visited the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the studio of Matthew Maris in London.

Ryder’s technique became more and more painstaking. He would repeatedly paint over his paintings, seeking an ideal composition. Paintings were worked on for years. Ryder called this process “ripening.” His works glowed from many layers of glaze. Unfortunately, the many thick layers of paint on his “little gems” have since cracked, and the glowing translucent varnish has darkened.

In 1888 a friend of Ryder’s, a waiter he met in his brother’s hotel, bet his $500 savings on a horse in the Brooklyn Handicap. When he lost his money, he shot himself. Distressed by his friend’s suicide, Ryder painted The Race Track, his most haunting symbolist work, considered by many to be decades ahead of its time. The painting, which is sometimes called “Death on a Pale Horse,” depicts the grim reaper riding a pale horse clockwise around a race track under a somber sky.

Starting in the late 1880s Ryder produced paintings of literary and religious subjects. Although these works are small in scale—as are all Ryder paintings—they are ambitious and grand, as well as sincere and powerful. Ryder began no new paintings after he turned 50, though he continued to work on many canvases that were still ripening in his studio.

As Ryder grew older, his artistic reputation grew, his paintings commanded higher prices, and young artists, such as Arthur B. Davies and Marsden Hartley, sought him out. Ryder had not been included in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but in 1913, 10 of his works were hung in the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York City.

Ryder’s kidneys began to fail in 1915. He eventually moved in with his friends Charles and Louise Fitzpatrick in Elmhurst, Long Island. He died in their home on March 28, 1917. The Metropolitan Museum of Art held a memorial exhibition of his work a year later. Evidence of Ryder’s esteem is his holding second place among forged American artists, with nearly 1,000 known forgeries of his paintings.

Further reading: William Innis Homer and Lloyd Goodrich, Albert Pinkham Ryder: Painter of Dreams (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989).

—Jan Hoogenboom

Saint-Gaudens, Augustus (1848-1907) sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, arguably America’s preeminent sculptor in the late 19th century, was known both for his monumental public sculpture and smaller private commissions. A major figure in the American Renaissance, Saint-Gaudens introduced an appealing naturalism in a sculptural lineage stretching back to classical antiquity. Of French and Irish extraction, born on March 1, 1848, in Dublin, the son of a shoemaker, Saint-Gaudens moved to America as an infant. He apprenticed for three years as a cameo cutter in New York City. In 1866 he entered the National Academy of Design in New York City, and in 1868 he enrolled in the studio of Francois Jouffroy of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1877 he married Augusta Homer, from a prominent Boston family. The artist also kept a mistress, Davida Clark, a model whose features can be traced in many sculptures.

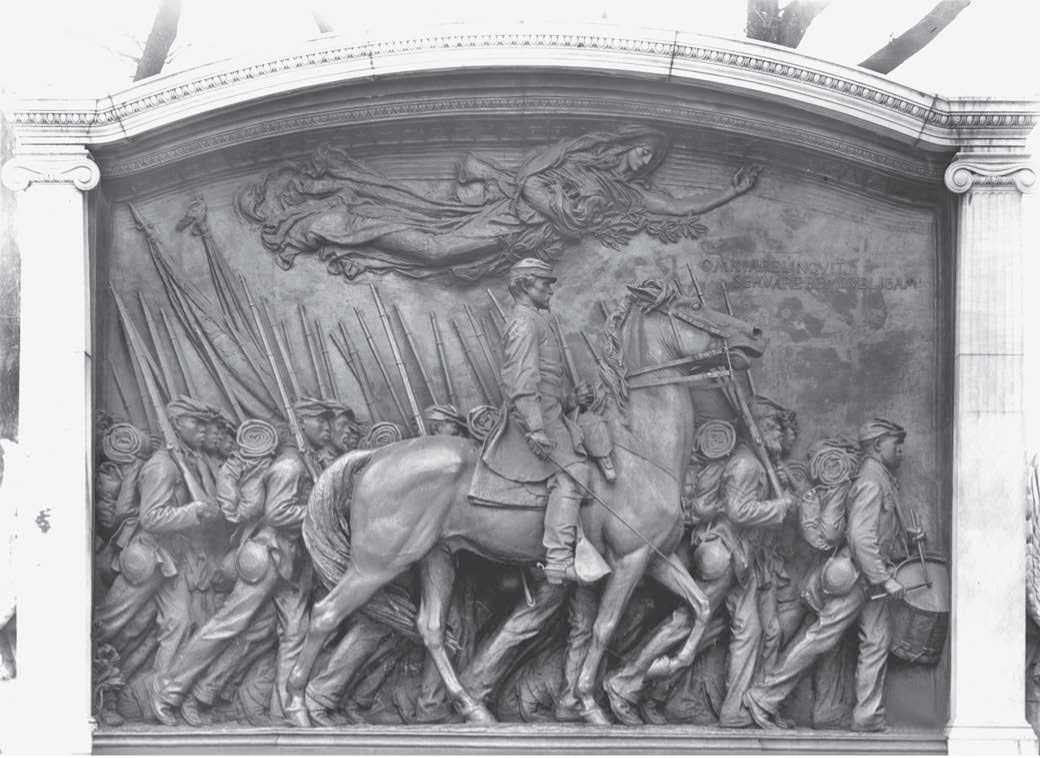

When in 1876 he won the commission for the Far-ragwt Monument (1881, Madison Square Park, New York), Saint-Gaudens became a leading figure in public sculpture. Most of his work focused on the human figure and was executed in marble or bronze. Saint-Gaudens often collaborated with his friend, architect Stanford White, in the design and setting of monuments. Among his most prominent public works were the Shaw Memorial (1897, Boston Common), Abraham Lincoln (1906, Grant Park, Chicago), and Diana (1891), which stood atop the spire of the original Madison Square Garden but is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He was instrumental in many organizations, including the Society of American Artists, the American Academy in Rome, and the sculptural commissions for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the Library of Congress.

Once awarded a contract for a major sculpture, Saint-Gaudens took a long time to complete it. He began with numerous drawings and proceeded to small-scale clay maquettes. He often retained these for years, examining, adjusting, and sometimes radically reworking his original conception. In studios in New York City, Paris, and later Aspet, his country home in Cornish, New Hampshire, Saint-Gaudens gathered congenial assistants, who produced the large-scale clay and plaster models used to cast the completed works. Many of Saint-Gaudens’s sculptures exist in different versions and scales; they represent various stages in the process from conception to casting. On August 3, 1907, Saint Gaudens died at Aspet, which is a now a museum of his work.

Saint-Gaudens’s genius lay in uniting the real and the ideal. His numerous bas-relief portraits, such as Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer (1888, Metropolitan Museum of Art), are charming in their immediacy and delicate realism. He was capable of startling synthesis in his allegorical works. The Adams Memorial (1891, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington), a funerary monument commissioned by historian Henry Adams after the suicide of his wife, used both Buddhist literature and Michelangelo’s Sibyls as sources. Describing the heavily draped, meditative figure, Adams wrote: “The whole meaning and feeling of the figure is its universality.” General Sherman Led by Victory (1903, Grand Army Plaza, New York) successfully quotes venerable antique sculpture while expressing the vitality of the Civil War commander. The Shaw Memorial commemorates the sacrifice of Robert Gould Shaw and conveys the determination of his men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry as they fought.

Further reading: John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Hanover, N. H.: University Press of New England, 1982); Burke Wilkinson, Uncommon Clay: The Life and Works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985).

—Karen Zukowski

The Shaw Memorial in Boston, sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1897 (Library of Congress)

World History

World History