Abortion refers to the intentional interruption of a pregnancy before birth, resulting in or accompanying the removal of the fetus. Though the procedure has been allowed in all 50 states since 1973, abortion has remained a source of social, political, ethical, and religious debate. Abortion deals with fundamental issues of civil liberties, civil rights, and morality. Those who support abortion rights argue that the government must not interfere with a woman’s right to choose whether or not to reproduce. Those who oppose abortion argue that it violates the rights of the unborn. Currently, case law and political mandates in the United States tend to favor the first interpretation. It is clear, however, that the debate over legalized abortion is far from resolved.

The first state laws explicitly forbidding the practice passed during the religious revivalism of the 1820s. By 1900 every state except one made abortion a serious crime. Changes in attitude arose from the post-World War II concern for overpopulation, as well as reproductive rights for women. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, women’s rights advocates joined forces with public policy research institutions like the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation to control world overpopulation and extend reproductive rights for women through national and international family planning programs. Though the initial goals of family planning involved public education and inexpensive distribution of contraception, by the end of the 1960s the efforts had expanded to include legalized abortion. Concurrently, women’s rights advocates campaigned for changes in the state statutes and succeeded in significantly loosening the abortion restrictions

Pro-choice demonstrators in New York City, 1977 (Hulton/Archive)

In 14 states before 1973. In 1973 the U. S. Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade and its companion case, Doe v. Bolton, found abortion to be protected by the constitutional right of privacy.

Roe declared unconstitutional any but the most lenient regulations on abortion during the earliest stages of pregnancy. States were allowed to restrict abortions during the last trimester, but only if they provided an exception for cases where the life of the mother was at risk. This landmark decision established two legal constructs. The first stipulated that women’s right to privacy included their reproductive organs and processes, as well as those dependent human embryos formed therein. The second suggested that a threshold existed between utter dependency and human viability. According to the Court, “developing life” could expect greater protections under the law during the last trimester because it was more likely to sustain itself outside the mother’s womb. The Court reasoned that the rights of the unborn superseded the mother’s right to privacy upon viability. Both opponents and supporters remained unsatisfied by this decision; mothers were accorded more specific rights over their reproduction decisions, while at the same time, limited protections under the law were also extended to the unborn, according to their viability.

Both decisions produced immediate backlash in the mid-1970s. Only New York had laws on the books that met the stringent guidelines of the new decision. Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington possessed laws similar to New York’s, and were able to meet the new standard set by Bolton by removing residency requirements. The laws of the remaining 46 states were invalidated. The attorneys general of Indiana and Montana claimed that the decision was inapplicable to their states, while legislators in Utah, Michigan, and Rhode Island attempted to pass laws setting the Court’s ruling aside. The Court issued a directive prohibiting any deviations from the new Roe and Bolton standards. At the same time, it rejected the petitions of 15 states calling for a rehearing of the case. After this, states looked for less direct ways of restricting abortion. In 1977 the U. S. Congress passed the Hyde Amendment ending federal funding of most abortions. By the end of the decade, 37 states followed suit by rescinding state funding for abortions, limiting advertising for abortion services, and requiring spousal consent for married women and parental permission for minors.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Supreme Court heard dozens of cases involving abortion regulations. In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), the Court prohibited state restrictions on advertising. The following year, Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth (1976) prohibited laws requiring spousal consent, as well as those statutes requiring parental consent without providing the alternative of a judicial waiver. The Court reconsidered the question of parental consent several times, finally concluding that states could require parental notification by a physician as long as minors had access to judicial waivers. Maher v. Roe and Beal v. Doe upheld state restrictions of abortion funding, and Harris v. McRae upheld the Hyde amendment’s prohibition of federally funded abortion services. Abortion rights advocates became increasingly concerned that the new decisions were chipping away at Roe v.

Wade. In contrast, abortion opponents remained frustrated that none of them specifically questioned the basic assumptions of abortion rights.

Immediately following Roe v. Wade, the National Council of Catholic Bishops led the charge against the new interpretation through lobbying efforts, and initiated education programs emphasizing the innate value of all human life. Five years earlier in 1968 Pope Paul VI promulgated the encyclical Humanae Vitae, which officially proclaimed the church’s opposition to contraception and abortion. Since legalized abortion was still a rarity at the time of the encyclical’s release, most Catholics and non-Catholics were concerned principally about those sections regarding artificial contraception. While many leading American Catholics publicly disavowed the encyclical’s prohibition of artificial BIRTH CONTROL, their disagreement did not extend to abortion. After 1973 most Roman Catholics supported their bishops in opposition to Roe v. Wade. At the same time, other religious leaders also voiced their opposition to legalized abortion. Many African-American leaders, such as Rev. jESSE L. Jackson, feared that abortion represented a form of eugenics aimed at limiting the size and strength of the black community in America. (Jackson later changed

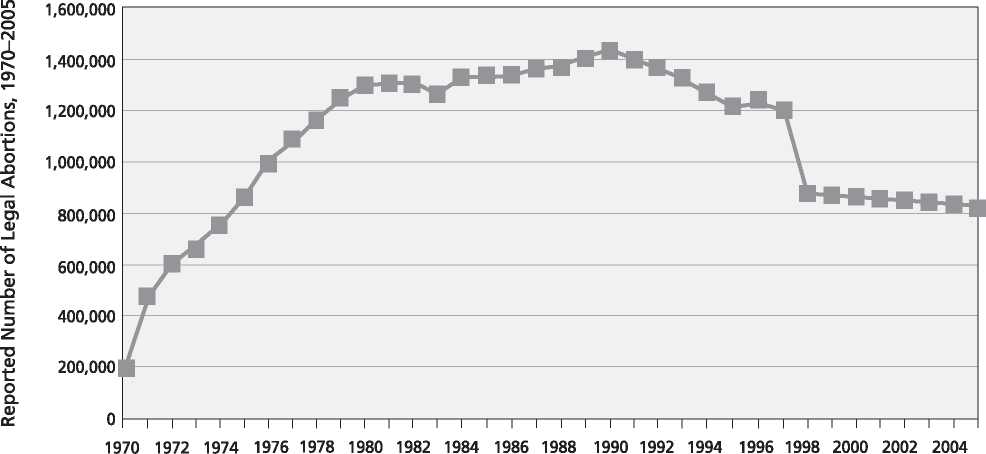

Number of Abortions

World History

World History