The spectacularly corrupt Tweed Ring was led by William M. Tweed (1823-78), who held a number of municipal posts in New York City in the 1860s, including deputy street

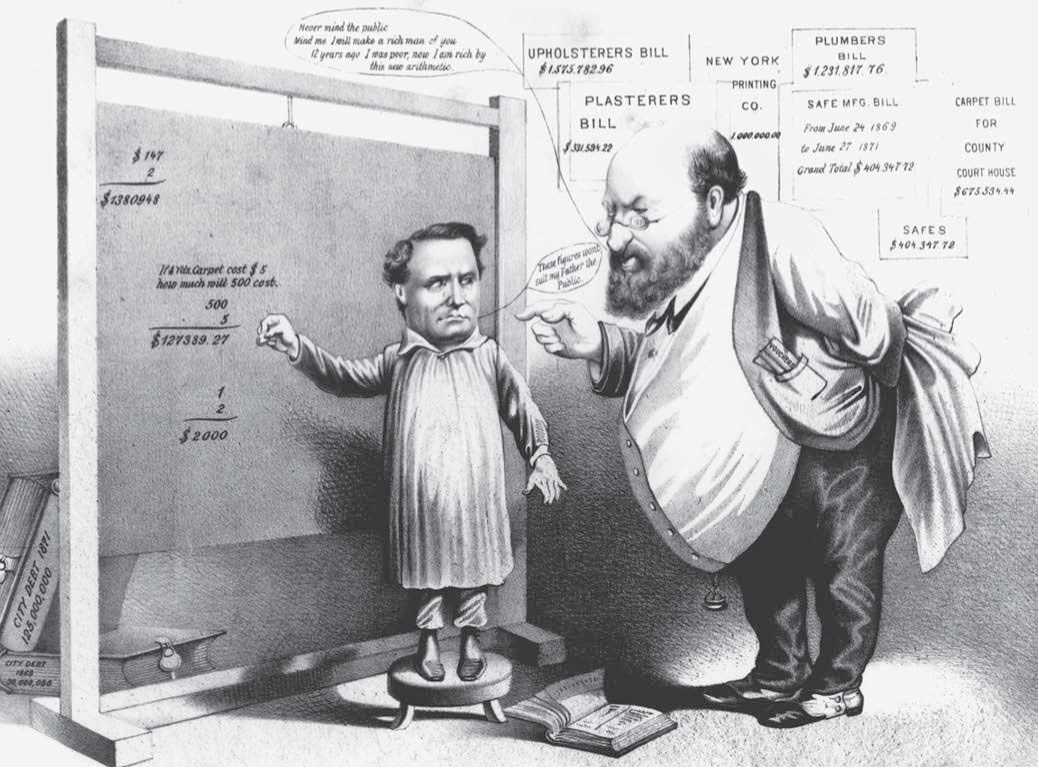

A political cartoon portraying William M. Tweed as a bullying schoolteacher giving New York City comptroller Richard B. Connolly a lesson in arithmetic. The exaggerated bills for the building of a county courthouse are posted on the wall. (Library of Congress)

Commissioner and deputy commissioner of public works. He increased his power through his control of appointments and the awarding of contracts, and by 1868 he was the leader of the Democratic machine, the grand sachem (leader) of Tammany Hall, and in complete control of the administration of New York City. Taking advantage of home-rule features in a new city charter secured by bribery from the New York State legislature, Tweed and his close associates—Mayor A. Oakey Hall, Peter B. Sweeny, and Richard B. Connolly—began in 1869 to steal from the city on so spectacular and so organized a scale that the Tweed Ring has overshadowed all other municipal corruptionists in American history. Its most conspicuous, but certainly not the only, source of graft was the construction of the new county courthouse. Not only did contractors purchase building materials from companies in which Tweed had an interest, but they also padded their bills and shared excessive payments with the ring. Since Tweed was on the Board of Audit, these fraudulent bills were not challenged. When construction was finished, the cost of the $12 million courthouse had been multiplied three times.

The Tweed Ring was short-lived. The cartoonist Thomas Nast began in 1870 to attack Tweed and his cohorts with devastating caricatures in Harper’s Weekly, and the ring’s downfall came in 1871 when disgruntled insiders leaked damning evidence to the New York Times.

Citizens were aroused. Samuel J. Tilden, the state Democratic leader, belatedly turned on Tweed (enhancing his reform reputation), and Tweed was overthrown, prosecuted, and convicted in 1873 for not properly auditing bills. He was imprisoned, escaped to Spain, but was extradited and returned to jail, where he died.

The effrontery of the Tweed Ring and the sheer volume of its stealings—perhaps as much as the $30 million Tilden alleged—obscures the rapid development of New York during the years Tweed was in power. Extraordinary municipal graft required extensive civic projects, including improved transit facilities, the widening of Broadway, and the development of Central Park. Payoffs and graft were powerful incentives that brought disparate elements, which normally paralyzed action, together to work (and steal) in concert on major undertakings. Indeed, the urban historian Seymour J. Mandelbaum argues that by uniting fragmented neighborhoods and ignoring the frugality prized by taxpayers and the morals of reformers, Tweed and his accomplices stole the city rich.

Further reading: A. B. Callow, The Tweed Ring (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985); Leo Hershkowitz, Tweed’s New York: Another Look (Garden City, N. Y.: Anchor Books, 1977); Seymour J. Mandelbaum, Boss Tweed’s New York (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1965).

World History

World History