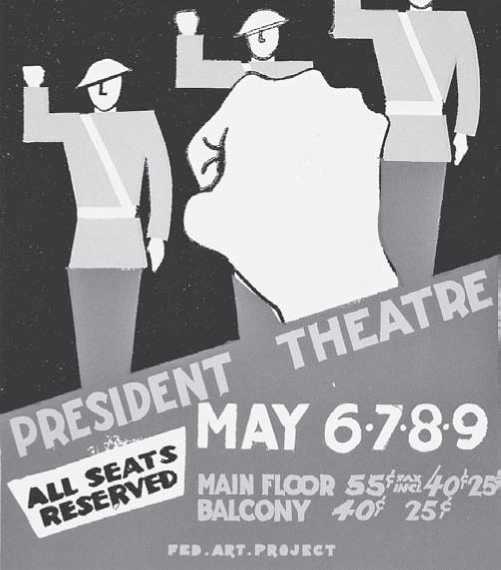

Poster for the theatrical staging of Sinclair Lewis's It Can't Happen Here (1935) (Library of Congress)

Encountered by most other New Deal relief programs. Formed as a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Federal Theatre Project, together with the Federal Writers’ Project, the Federal Art Project, and the Federal Music Project, made up an effort known collectively as Federal One to provide work relief for the arts. The FTP became the most controversial of these programs.

Hallie Flanagan, a Grinnell College classmate of New Deal relief administrator Harry Hopkins and head of Vassar College’s Experimental Theatre, was chosen to lead the Federal Theatre Project. Enthusiastic about the FTP and its possibilities from the very beginning, the dynamic Flanagan believed that the project could and should be used for the creation of a socially relevant theater. She and the other project organizers intended to spread the FTP across the United States. Each region would have its own center, with local theaters established in the surrounding communities. Personnel would be recruited locally.

A thriving federal theater took root only in three cities. New York City had the most important programs, but Los Angeles and Chicago also built successful projects and loyal audiences. Actors of varied backgrounds and experience shared the stage. Successful productions resulted, including Orson Welles’s production of Macbeth with an all-black cast and It Can’-t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis’s controversial play about fascism. FTP audiences ultimately totaled an estimated 30 million people, and the program provided employment for thousands of theater people.

Despite its successes and the public support it gained, the Federal Theatre Project encountered a variety of challenges and problems. One of the most important issues faced by the FTP was whether the chief goal was to provide work relief or to create a quality theater, a debate that was never satisfactorily settled. Facing pressure from Washington to place workers on the payroll as quickly as possible in order to meet relief needs, many regional projects hired actors without auditioning them first. The result was typically an underqualified or inexperienced workforce. Challenges also came from the unions, which demanded that specific hours limitations be placed on workers; consequently, opening dates were often pushed back to allow for further rehearsals. In addition, commercial theater criticized the federal productions, claiming that they led to unfair competition.

Another problem that Flanagan faced was that she frequently lost well-qualified staff members because of the frustrations of working with uncooperative or unsympathetic government officials. Within six months after the creation of the Federal Theatre Project, two-thirds of the original 24 regional directors had resigned their posts. Bureaucrats or relief workers with little or no interest in the artistic attributes of the project often replaced these valuable personnel.

A significant aspect of Hallie Flanagan’s plan for a socially relevant theater was the creation of what were called Living Newspapers. The goal of these productions was to draw the public’s attention to contemporary social or political issues. All were commercially successful, but each one also faced criticism from people in government. Members of Congress who were quoted in one production felt that they had been misrepresented by the context in which their words were placed.

In 1938, the project came under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee, led by the conservative Texas Democratic congressman Martin Dies. Accusations of New Deal propaganda and Communist sympathies in the FTP had been leveled for some time, from both inside and outside sources. For several weeks, witnesses were brought before the committee to testify about alleged—and sometimes real—radical and Communist activities within the FTP. When Hallie Flanagan appeared before the committee to defend the FTP, she was only allowed one morning in which to make her case, and was not permitted to complete her argument. By the time the investigations closed in late 1938, national public support for the Federal Theatre Project was dwindling.

Despite the negative publicity of the period during and immediately following the Dies committee hearings, successful shows continued to be produced in the major centers. However, the Federal Theatre Project was an endangered institution. It encountered not only ideological opposition but also criticism that its operations (and money) were focused too narrowly on New York and a few other big cities. In 1939, when the other Federal One arts projects were placed under state control, the Federal Theatre Project was abolished completely. Subsequent attempts to reinstate the project in 1940 and 1941 proved unsuccessful.

Further reading: Jane DeHart Mathews, The Federal Theatre 1935-1939: Plays, Relief, and Politics (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1967); William F. McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Project Administration (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969).

—Joanna Smith

World History

World History