As the allied armies approached, Paris was in no condition to withstand them. Some fortifications had been hastily improvised, but they were wholly inadequate. Joseph Bonaparte, in command of the city as his brother’s deputy, made regular tours of inspection, but this impressed nobody. As he was setting off on one of them, a staff officer asked where he was going. General Dejean, accompanying Joseph, replied: ‘To visit an incomplete and useless defence system dreamt up by incompetents.’ To man these inadequate lines, Joseph had just 42,000 men—30,000 of these were regular troops under Marshals Marmont and Mortier. The rest were National Guard, 3,000 of whom were armed only with pikes. The disappointing numbers of National Guard were an inevitable consequence of the decision taken two months earlier to limit their recruitment to middle - and upper-class citizens.1

In these circumstances, the only effective way to defend Paris was to distribute weapons to the population. Yet a government that had baulked at including workers in the National Guard was hardly likely to take this far more radical measure. With its memories of the Revolution, it feared arming the Parisians even more than being overwhelmed by the invaders. On 16 March, Pasquier wrote to the interior minister Montalivet: ‘Above aU we must avoid stirring up the population of Paris. There is no knowing where this might lead. Once roused it could easily be led astray by all sorts of factions. It is in great distress. It would be very easy to encourage it to acts of despair against the government, and there is no lack of people ready to exploit these feelings.’2 It was perhaps no coincidence that Pasquier’s father had been guillotined in Paris during the Terror.

In fact, Pasquier need not have worried, since most Parisians were in no mood to fight anybody. Instead, their dominant emotion was fear. They knew that a large part of the enemy army was Russian, and were terrified

That it might take revenge for the destruction of Moscow by burning Paris to the ground. Their alarm was heightened by the increasing flood of refugees from the surrounding countryside, with tales of wild Cossacks and their depredations. In late March, Marshal Macdonald’s daughter Nancy wrote to her father at the front:

This morning the gates of Paris were swamped by farm animals and peasants’ carts carrying furniture. Everyone on the road from Meaux... is arriving and spreading consternation; but the weather is so fine that it gives us courage, and the approach of the enemy and the horrors they are committing have been talked of so much that we’re getting used to it. But if a shell landed on Paris and even if we heard the sound of cannon, which we might tonight, that would be very frightening. What will become of us? I still trust in Providence, which will not permit the centre of civilization to be swallowed up or conquered by the barbarians.3

Amid the panic and confusion, one man in particular kept his nerve and his head—Talleyrand. The former foreign minister occupied an ambiguous position, deeply distrusted by Napoleon, but still a grand dignitary of state, and as such sitting on the regency council. His role in the crucial

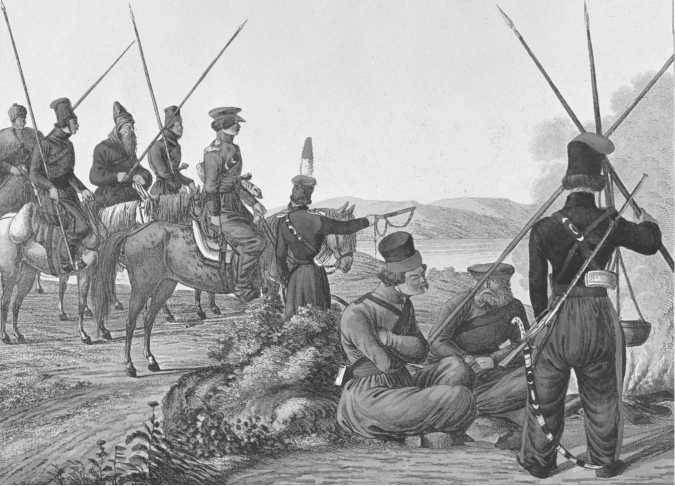

Figure 10. Cossacks on campaign in France, 1814.

Days of March and April 1814 was pivotal, and remains controversial. He is generally depicted as working throughout this time for a Bourbon restoration, having decided that Napoleon was a lost cause.4 Yet this view ignores considerable evidence that up to a very late stage his preferred option was not the return of the king, but a regency exercised by Marie-Louise on behalf of Napoleon’s infant son. Talleyrand had certainly decided that peace was impossible with Napoleon as head of state. On a personal level, he had been in semi-disgrace since 1809, and had nothing more to hope for from the Emperor himself. A regency, on the contrary, had considerable attractions. It was far more compatible with post-revolutionary France than the Bourbons, and Talleyrand himself was the obvious candidate to become Marie-Louise’s prime minister. In this role, he would be following an illustrious precedent—that of Cardinal Mazarin, who had steered the policy of another Habsburg-born regent of France, Anne of Austria, during Louis XlV’s minority.

The most solid source for Talleyrand’s intrigues to bring about a regency is Caulaincourt. Not only was he an old friend and protege of Talleyrand, he was also close to Talleyrand’s most important collaborator at the time, the councillor of state Emeric, duc de Dalberg. Although Caulaincourt was at Chatillon and then at Napoleon’s headquarters in March 1814, Dalberg was in Paris throughout and gave him detailed information on the events there for his memoirs.5 Reports also reached Caulaincourt that Talleyrand’s machinations extended beyond Paris. An undated note in his papers reads:

Before the 21st March, it is said, Talleyrand’s agents told leading citizens of Lille that everything was ready for a regency, that it was agreed, that it was impossible that the Emperor would not be killed in the continuous fighting, and that the regency would be proclaimed, with a council composed of Cambaceres, Talleyrand, and three others.6

The expectation of Napoleon’s death in battle this note evokes is telling. The major problem facing the partisans of a regency was how to dispose of the Emperor. Alive, he would be a major obstacle to the scheme. Only the direst circumstances would persuade him to abdicate in favour of his son. Even if he did and went into exile, he would remain a constant presence in the wings, attempting to direct his successor’s actions. The most convenient solution was an enemy bullet or sabre, and Talleyrand clearly hoped that this would resolve his dilemma. On 20 March, in a letter that chimed exactly with the rumours Caulaincourt was picking up, he

Wrote to his niece the duchesse de Dino: ‘If the Emperor were kiUed, his death would guarantee the rights of his son... The regency would satisfy everyone because a council would be named that would satisfy all shades of Opinion.

Talleyrand’s manoeuvres are always difficult to follow, and he complicated them further by making discreet contact with both the Bourbons and the allies. Through his confidante Aimee de Coigny, connected to the Chevaliers de la Foi through her lover Bruno de Boisgelin, he first sent a message to Louis XVIII assuring him of his goodwill. Then, in early March, he despatched a friend of Dalberg, the royalist agent the baron de VitroUes, to allied headquarters with the advice to march directly on Paris. Neither action committed Talleyrand to anything; he was careful to act only through go-betweens, and committed nothing to paper himself. The overture to the Bourbons was a sensible insurance measure, since they were the obvious alternative if the regency should prove impossible. As for urging the allies to make straight for the capital, this was the shortest way to achieving Talleyrand’s primary goal, the downfall of Napoleon.8

Whether Napoleon was kiUed or not, the chances of establishing a regency depended on Marie-Louise and her son remaining in Paris. However brilliantly the Emperor fought, Talleyrand was certain that he was doomed, and that the allies would soon capture the capital. At that moment, it was vital that they find the Empress and the king of Rome firmly installed there, as the legitimate rulers of France. This would make it very difficult for the allies, and particularly for Marie-Louise’s father Francis I, to avoid recognizing the regency. For his part, Napoleon was fully aware of Talleyrand’s aims. Discussing them retrospectively with Caulaincourt a few weeks later, he observed:

I am certain that Talleyrand wanted... the regency; this form of government would have suited both him and M de Metternich, who was always his ally. You can be sure that Talleyrand had long ago prepared his arrangements were I to die at the head of the army. Since no bullet found me, he still wanted to act as if I was no longer there. This no doubt was his reason for wishing to keep Marie-Louise in Paris; he would have made her his instrument and his protectress.9

Most rulers feel uncomfortable when others plan for the event of their demise. Yet Talleyrand was at least trying to keep the Bonaparte dynasty in power. Remarkably, Napoleon saw this as a betrayal equivalent to declaring for the Bourbons. In his desperate letter to his brother Joseph of 8 February,

He added: ‘If Talleyrand supports the argument that the Empress should stay in Paris if our troops have to evacuate it, then treason is being plotted.’ Clearly, Napoleon’s definition of treason included any attempt to save his son’s throne while he himself was still alive.

The decisive moment came at a meeting of the regency council on 28 March. That day the allied army reached Meaux, just over thirty miles east of Paris, and the question of Marie-Louise’s departure could no longer be deferred. There are several accounts of what happened at the council, but the most detailed is an unpublished one by Caulaincourt. This claims that of the twenty-two members present, nineteen voted for Marie-Louise to stay, including Talleyrand, Cambaceres, and Savary. Talleyrand was particularly eloquent. According to Caulaincourt, ‘he went up to the Empress during a pause in the meeting and begged her to weigh the consequences of the decision she was being urged to take... What was there to fear in Paris with loyal troops whose example would galvanize all classes of citizens? The worst thing would be to abandon them... to deprive them of the rallying-point that had been entrusted to their courage.’11

At this juncture, with the overwhelming majority present in favour of staying, Joseph Bonaparte intervened. First he read out Napoleon’s letter of 8 February insisting that his wife and son leave the capital if it seemed about to fall, then a second one confirming this, written on 16 March. The reaction round the table was first shock, then anger. ‘Why bother to consult us’, burst out several councillors, ‘if the Emperor’s orders leave us no choice?’ Caulaincourt adds that everyone at the meeting was aware of Napoleon’s reasoning, and most disagreed strongly with it:

It was known that the Emperor, who was aware that there had been talk of and even some plans for a regency that would remove him and put his son in his place, had ordered: Treat as a traitor anyone who proposes that the Empress should stay in Paris. Most of the ministers deplored the fact that the Emperor’s suspicions were depriving the capital and the empire of their only hope of salvation.

Talleyrand still tried to fight back even after the council had broken up, going to Marie-Louise and urging her to stay despite Napoleon’s instructions. The empress’s own instinct was to remain. But she did not feel able to disobey a direct order from her husband. The next day she and the 3 - year-old king of Rome left the Tuileries for Blois, in a lumbering convoy

Including the imperial coronation coach covered with a cloth. As Caulain-court damningly put it, ‘her departure had all the pomp of a funeral’.13

Marie-Louise’s flight had the worst possible effect on the capital. As Pasquier put it in his daily bulletin, it caused ‘the most painful sensation’.14 To the Parisians preparing to withstand a siege, it sent a message that the government had given up the fight in advance. It also profoundly alienated the Senate. When Cambaceres notified them that the empress had left, the senators made their disapproval plain. They also felt slighted by the curtness of the announcement, which was not accompanied, as was usually the case, by a detailed report. This mishandling of the Senate had important consequences. Had its members not been angry at being treated so cavalierly, they might not have acted the way they did a few days later.15

The news that Marie-Louise had abandoned Paris was brought to Talleyrand at his house in the Rue St Florentin, as he was talking with Dalberg and the banker Perregaux. According to Dalberg, Talleyrand ‘was silent for a short while, then, resting his knee on a chair by the window, observed that everything was lost. “[The Empress] hasn’t understood how important it was for her to stay. This departure changes everything. It’s a great event”, he repeated several times.’16 It was at this moment, and not before, that Talleyrand switched his allegiance to the Bourbons. His efforts to save the Bonaparte dynasty through a regency had compromised beyond repair his relations with Napoleon. If the Emperor managed to relieve the capital, Talleyrand would probably be arrested. Now Marie-Louise, on whom the regency plan depended, had removed herself from the stage. For selfpreservation as much as policy, Talleyrand had no choice but to rally to Louis XVIII.

From this point on Talleyrand had two aims: to make himself indispensable to a Bourbon restoration, and to ensure his own safety. To achieve them, it was essential that he himselfstayed in Paris, and that Napoleon did not return. Joseph and the government had been ordered to follow Marie-Louise to Blois, and left the capital on 30 March. Talleyrand avoided doing so by a manoeuvre that was transparent but which served its purpose. That evening he presented himself at the city gates, having secretly arranged beforehand to be turned back by the National Guard. He could thus claim that he had tried to follow Napoleon’s instructions, but had been prevented from doing so by over-zealous officials. He then returned to the Rue St Florentin to await, and attempt to shape, events.17

Talleyrand’s next step was to communicate his thoughts to his inner circle. The reaction was at best lukewarm. His friends expressed grave doubts about restoring the Bourbons, arguing that the family had not learned the lessons of the Revolution, and citing as evidence references to divine right in Louis XVIII’s previous proclamations. Talleyrand replied rather airily that the comte d’Artois might have such notions, but that Louis XVIII, ‘having always had more liberal ideas and having lived in England would return with the desired opinions’. In the heat of the moment, Talleyrand was making a dangerous assumption. As it turned out, the Bourbons would prove less tractable and ‘constitutional’ than he expected.18

The same day the allies launched their assault on Paris from the north. Initially, Marmont’s troops managed to contain it around the outlying villages of Pantin and Romainville. However, the main allied attack, delivered at 3 p. m. with forces more than double those of the defenders, was impossible to withstand. One and a half hours later, the French lines had been broken, and the strategic heights ofMontmartre taken. The capital was now at the invaders’ mercy, and Marmont and Mortier felt they had no option but to surrender. At two the following morning, 31 March, the capitulation of Paris was signed. The struggle for its possession had cost each side 9,000 casualties. With the outcome a foregone conclusion, it was the bloodiest, and most useless, battle of the 1814 campaign.19

Within hours Marmont’s and Mortier’s soldiers had evacuated the city. A brief, eerie calm feU on its deserted streets. It was broken at 7 a. m. by the appearance of three horsemen—the Russian foreign minister Nesselrode, accompanied by two Cossacks.20 They made straight for the Rue St Flor-entin, to Talleyrand’s house. The discreet message of support Talleyrand had sent had been noted by the allies, and they had decided that they needed his expertise on their side. Nesselrode informed Talleyrand that during his time in Paris the Czar wished not only to take Talleyrand’s political advice but also to stay in his house, making it the allied headquarters. The question of who would now rule France would be decided under Talleyrand’s own roof.

World History

World History