GEOGRAPHY

Serbia and Montenegro border Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, Albania and Macedonia to the south, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west, and the Adriatic Sea to the southwest. The total area is 39,449 square miles. Fertile plains are situated in the north; the Dinaric Alps lie in the southwest; and basins of the Carpathian and Baltic Mountains lie in the east. Mount Daravica (8,714 feet), the highest peak, is located along the Albanian-Montenegrin border. Principal rivers include the Danube, Drava, Sava, Drina, and Tisza. Lake Scutari is the country’s largest lake.

INCEPTION as a nation

Tribal Serbs first occupied the Balkans during the sixth and seventh centuries c. e. and were unified in a Serbian nation, Rascia, around the ninth century. Rascia expanded its territory during the 10th century although subject to the Byzantines. Serbia continued to expand in the 13th and 14th centuries, notably under the leadership of Stephen Dusan. Ottoman Turks (see Turkics) invaded the territory, and in 1459 Serbia lost its independence to them. For centuries Serbia was a Turkish province ruled by local Turkish officials out of Belgrade. Serbs won brief independence under the Treaty of Bucharest in 1812, ending the Russo-Turkish War, and in 1817, after a successful rebellion, Milos Obrenovic declared himself Prince of Serbia.

By the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829 Russia forced Turkey to recognize an autonomous

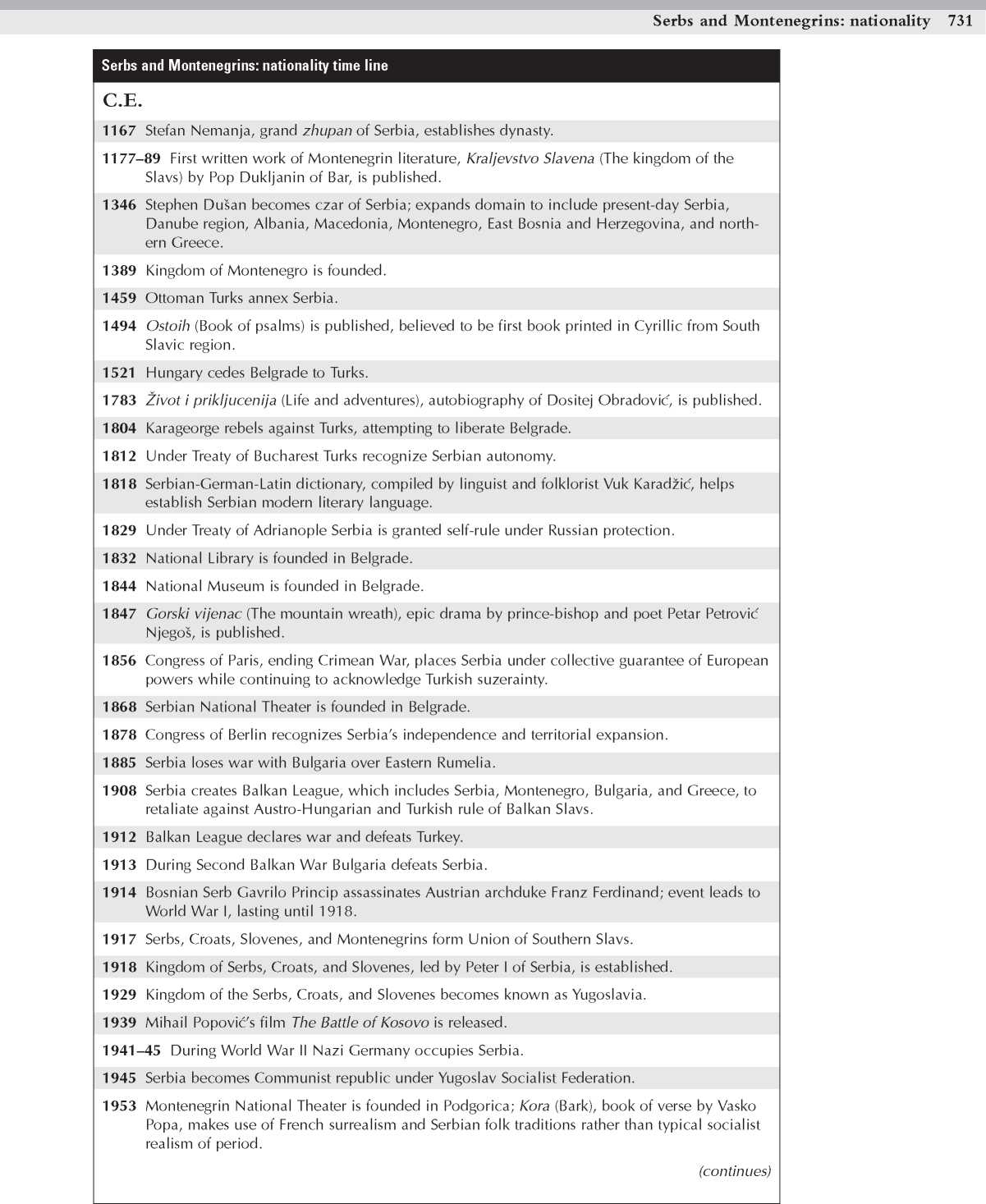

Serbs and Montenegrins: nationality time line (continued)

1961 Novelist Ivo Andric wins Nobel Prize in literature.

1971 Belgrade International Film Festival is founded.

1989 Serbia invades Kosovo, ending its autonomy.

1992 Serbia and Montenegro form Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

1998-99 Secessionist rebellion in Kosovo against Federal Republic of Yugoslavia ends in bombing of Yugoslavia by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and withdrawal of Serbian forces.

2001 Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Albania reestablish diplomatic relations.

2002 Montenegrin government collapses over differences on new union of Serbia and Montenegro.

2003 Federal Republic of Yugoslavia becomes Serbia and Montenegro.

Serbia. Serbia declared war on Turkey in 1876, once again drawing Russian aid into the conflict. By 1878 the Congress of Berlin recognized a completely independent Serbia and expanded its borders.

Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. The various Balkans powers struggled over territory in the two Balkan Wars (1912-13). The assassination of the Austrian archduke Francis Ferdinand by a Serbian nationalist in 1914 led to the outbreak of World War I. At the end of the war, in 1918, Serbia’s former territory became the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which became known as Yugoslavia in 1929.

The German invasion of 1941 led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia; at the end of World War II in 1945 it was reconstructed; it changed its name to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963. In 1991-92 Yugoslavia broke up when Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence. In 1992 Serbia and Montenegro formed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Internal tensions between the two republics led to a pact in 2002, giving greater autonomy to each side yet retaining shared foreign and defense policies. The state union of Serbia and Montenegro was officially recognized in 2003.

CULTURAL IDENTITY

The peoples of the state of Serbia and Montenegro, formerly the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), a recent political construct (or rather the remnants of an older political construct), do not share a common cultural identity. By far the most numerous people in the country, who constitute two-thirds of the population (about 10.5 million), are Serbs. The next most numerous group is made up of Albanians, 17 percent of the population. Montenegro has a population of somewhat less than 700,000, 60 percent of these Montenegrins (largely ancestrally Serbs but with a different historical tradition) and the rest Serbs, Albanians, and Muslims. The FRY was the remnant of the former Yugoslavia after its constituent republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, reacting to attempts at domination by the Serbs, all declared their independence. The makeup and indeed the very existence of the FRY were a consequence of modern Serbian aggression, and for many years among its most important objectives as a nation was active support of extreme Serbian nationalist aims in the neighboring countries of Bosnia and Croatia, support that led to war and a return to the geno-cidal tactics of World War II in what was infamously called “ethnic cleansing” of other groups by Serbs. The Serbian-dominated government engaged in human rights violations against minorities in the FRY, especially Albanians in Kosovo, who have resisted the Serbian government since the province lost its autonomy. A guerrilla group called the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) formed in the mid-1990s and targeted Serbian police repeatedly in late 1997 and early 1998. Actions of Serbian forces in their crackdown on Albanians in Kosovo were so severe that they were deemed war crimes by the International Criminal Court, and the Serbian president, Slobodan Milosevic, was indicted and tried in the Hague. After a peace accord was reached a United Nations peacekeeping force was stationed in Kosovo to protect returning Kosovars from the Serbians.

Montenegrins in the FRY distanced themselves as much as possible from the Serbs, splitting off from the Serbian orthodox Church to form their own, and as a result of political power plays by Milosevic in the federal government Montenegrins began to regard the federation as an illegitimate institution. Negotiations between Serbia and Montenegro in 2002 led to the creation in 2003 of a much looser federation of the two republics, one that could be dissolved by referendum by either republic after three years.

Given this historical context it is hardly surprising that the only national cultural identity most of the population in the federation maintain is the Serbian historical identity, recognized by Serbs. The atrocities fomented by the Serb-dominated government put great pressure on the self-identity of many Serbs who recognize that the actions of their government have been driven by a process of national cultural identification and promotion gone badly awry. The extremity of Serbia’s actions has generated international discussion in the Balkans, one that seeks means of developing, instead of a national cultural identification, a multicultural outlook that values differences among peoples instead of attempting to eliminate them by force and oppression.

Further Reading

John B. Allcock. Explaining Yugoslavia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

Eric D. Gordy. The Culture of Power in Serbia: Nationalism and the Destruction of Alternatives (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999).

Tim Judah. History, Myth, and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000).

John R. Lampe. Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Aleksandar Pavkovic. The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia: Nationalism in a Multinational State (New York: St. Martin’s, 2000).

Vjekoslav Perica. Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Frederick Bernard Singleton. A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Sessuvi See Esuvii.

World History

World History