PEACE CAME TO CANADA in instalments. Hitler’s war ended on May 6, 1945, with enough notice to civic authorities that most of them put out bunting and Union Jacks and arranged celebrations. In Halifax, where they did not, servicemen and women made their own entertainment, looting a brewery and downtown stores to avenge wartime profiteering. VJ-Day, less than four months later, was more spontaneous and less climactic: except to starving Canadian prisoners of war and their relatives, the Pacific War had never ranked with the war in Europe. Most Canadians still faced eastward to their origins.

In the post-war period, Canadians entered a time of prosperity that their forebears and, indeed, most of their fellow inhabitants of the world had never dreamed of For most Canadians, the old rituals of scarcity, hard times, and sacrifice were soon forgotten. The largest cohort Canada had ever bred grew to maturity taking its benefits for granted, grumbling at the side-effects, and transforming the lifestyles of a wealthy few into the consumption patterns of an affluent mass society.

The war years, with their full employment, steady income, and the Liberal promises of a “New Social Order” were a foretaste of the decades to come. For the rest of the world, the war had been at least twice as terrible as its predecessor; for most Canadians, it marked the end of the Great Depression. Canada emerged from the war with

42,000 dead—two-thirds the toll of the earlier war—the world’s third largest navy, and fourth largest air force. Much of Canada’s war effort had been devoted to expanding its industrial base. The war debt was manageable, and the nation’s vaults were stacked with foreign currency. For Canada, there were none of the costly colonial or overseas entanglements that trapped its larger allies. Africa, India, and the Caribbean had few Canadian connections. By the end of 1946, the last of its overseas forces were safely home and demobilized.

The government’s slogan for post-war reconstruction was “orderly decontrol.” The presiding genius was the same curt, rumpled engineer who had managed wartime production, C. D. Howe. His wartime “dollar-a-year” executives returned to their peacetime empires, but they remained a powerful political network for the one man in government they respected. For the most part, the corps of professional civil servants bred And trained in the war stayed on to give peacetime Ottawa an administrative competence it had rarely possessed before. One reason was that the new “mandarins” felt needed to prevent a recurrence of the disastrous Depression.

The prospect of a renewed depression had made Canadians approach war’s end with fear as well as joy. To judge from the public utterances of business leaders, they had learned nothing from the disaster of laissez-faire in the 1920s. As in 1919, peace meant freedom for old commercial habits. Within the government, a bitter struggle had raged between the proponents of a reversion to unfettered free enterprise and those concerned about the costly, uncharted future of a welfare state. In the end, both views prevailed. Free enterprise would pay for social reform. It was the combination of social reform and free enterprise that allowed Mackenzie King his narrow election victory on June 11,1945. By the end of that month, family allowance cheques had reached most Canadian mothers outside Quebec, where fathers initially got the money. For families with enough wartime savings for a down payment, the National Housing Act guaranteed low-cost mortgages. No other belligerent, even the United States, offered its veterans such generous opportunities for education, training, and re-establishment. Unemployment insurance, which officially took effect in 1941 when the jobless rate was literally zero, helped make the transition from war production to peacetime industrial jobs virtually painless. Means-tested old age pensions and provincially funded allowances for the blind and for abandoned mothers helped create a welfare system that was utterly unprecedented for Canadians.

Howe and his friends scorned “the Security Brigade,” as they termed those who had put the welfare network in place, but he could draw on a much older Canadian tradition

From San Francisco, where Canada tested her new “helpful fixer” role in the first session of the United Nations, William Lyon Mackenzie King and Louis St. Laurent tell Canadians—on May 8, 1945—that the war in Europe is over.

Of “corporate welfare” to achieve his share of post-war reconstruction. The rich incentives that had persuaded industrialists to convert to war production were used again to “reconvert.” Howe sold war plants at a tiny fraction of their cost to the taxpayers on condition that they be reopened for business. Faster write-offs—“accelerated depreciation”— and other tax devices worked as well in peacetime as during the war. Export insurance—with government underwriting the risks—encouraged businesses to sell abroad. Despite his contempt for socialism, Howe saw no irony in protecting the best and most innovative of his crown corporations, such as Eldorado Nuclear at Port Hope, Ontario, Polymer Corporation in Sarnia, Ontario, and his pre-war creation, Trans-Canada Airlines. Defence contracts helped guarantee that the wartime aircraft industry he had built would have an exciting and innovative future. Avro, a British-owned firm outside Toronto, launched the world’s first jet-powered airliner in 1947 before it was ordered to build Canada’s first jet fighter, the cf - 100 Canuck. Only government, Howe recognized, could give Canadians a future in science and technology. Otherwise, Howe believed, if Americans wanted to invest in Canada, their money was more than welcome.

Industrial reconversion, enhanced by a burst of spending power, banished any threat of a post-war depression. With a brief hesitation in 1945-46, industrial production soon climbed past its wartime peak. Veterans and former munitions workers found peacetime jobs and stayed in them. With post-war wages secure, Canadians could clamour for the homes, cars, furniture, and home appliances that had been beyond their means or simply unavailable for fifteen years. Organized labour, guaranteed a legal right to union recognition and collective bargaining by a wartime order-in-council, chose 1946 to prove to new members that unions could win them a share in the new prosperity. A bitter strike at the Ford Motor Company in Windsor, Ontario, in 1945 had established a basis for compulsory check-off of union dues, giving Canadian labour a financial security it had never known before. In turn, union militancy and prosperity combined to win workers high wages, paid vacations, and fringe benefits almost unknown in the pre-war years. By 1949, unions had become common in manufacturing and the resource industries, and almost 30 per cent of Canada’s industrial workers held union cards.

Without really admitting the fact, post-war Canada had evolved into a social democracy. Universal social programs, a strong union movement, and a state commitment to create jobs and eliminate regional disparities completed an evolution begun in the 1930s. Wartime experience and post-war prosperity had made it possible. Saskatchewan was rescued from bankruptcy and transformed into a laboratory for social innovation by the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (ccf) and its feisty

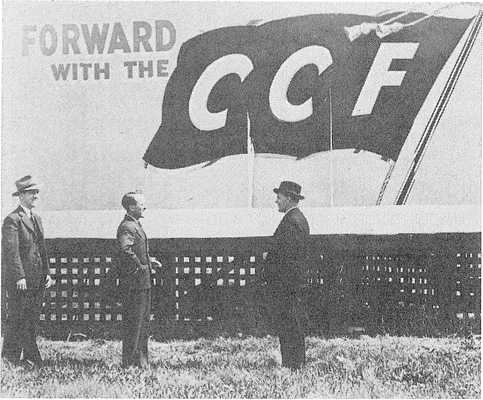

Only Saskatchewan followed the CCF banner after the war. The strength of the left-wing party was not in its slogans or the few billboards it could afford, but in the practical idealism of leaders like Tommy Douglas (centre), his provincial treasurer, Clarence Fines (left), and Clarie Gillis, the Cape Breton miner who held the only CCF seat east of Toronto.

Young premier, Tommy Douglas. Other Canadian provinces were more traditional. Most spent their growing revenue on paving highways or adding schools and hospitals to serve an exploding population. The initiatives came from Ottawa.

Canadian prosperity depended, as always, on trade. Industrialization increased Canada’s dependence on foreign capital, expertise, specialized products, and raw materials not available at home. In turn, the post-war world was eager for much that Canada could produce. Payment, of course, was another matter. Washington’s wartime policy of Lend-Lease ended abruptly with peace. In 1945, Britain and other bankrupt, devastated Allies were all faced with a blunt U. S. demand to pay up. In Washington, business was business. In an Ottawa desperate for markets, business was more complicated. It meant extending an immediate $2 billion credit to foreign buyers at a level—on a per capita basis—far more generous than even the later American-sponsored Economic Recovery Plan of 1948.

Ottawa’s credit scheme was a policy with acute limits. The more Canada produced for export—and for its own consumers—the more it had to import from the United States. Manufactured goods from Canadian factories were often heavy with American-made components. Favourable trade balances ranging from $250 million to $500 million in the post-war years were cold comfort if Canada was selling on credit but paying in hard American dollars. In 1947, Canada’s post-war reserve of $1.5 billion in U. S currency had tumbled to only US$500 million and was vanishing at the rate of $ 100 million a month. Prime Minister Mackenzie King was in London for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth, and it was unthinkable in his absence for his colleagues to summon Parliament. Instead, the finance minister simply imposed exchange controls and banned whatever U. S. imports Howe and his officials deemed non-essential. Canadians who wanted fresh vegetables that winter could eat cabbage or turnips. People grumbled and conformed. Parliament would not decide.

The crisis passed. Soon the developing Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies channelled U. S. investment dollars to Canada. Unnoticed in the developing exchange problem, Imperial Oil’s 134th drilling attempt outside Edmonton delivered a gusher on February 13, 1947. Soon a new industry delivered a rich export for Albertans and cut millions of dollars from Canada’s import bill. In 1948, the U. S. Congress, as part of its new Marshall Plan for foreign aid, renewed for Canada most of the advantages the two neighbours had enjoyed under the 1941 Hyde Park agreement. If Europe was to be saved from Communism, business could not just be business. Canada also became the closest, safest source of the minerals, from nickel to uranium, that U. S. strategic planners wanted to stockpile in case the Cold War turned hot.

The 1947 economic crisis and its aftermath were notification, if any was needed, that Canada’s prosperity now depended utterly on the United States. John Deutsch, a Saskatchewan farmer’s son and a gifted economist, persuaded fellow civil servants that it was time for theory to become practice. If tariffs were evh, abolish them. Several Liberal ministers were impressed by Deutsch’s case for Canada-U. S. free trade; their Prime Minister was more cautious. Defending reciprocity—Laurier’s version of free trade—had

Cost King his seat in the 1911 election. A long memory and growing concern about U. S. domination finally led King to veto the project. Indeed, he went

Joey Smallwood and the power of radio brought Newfoundland into Confederation in 1949. A former broadcaster, Smallwood used radio to force the Canadian option on the island leadership. His reward was almost twenty-three years of political domination of the new island-province.

The St. Lawrence Seaway, long promised, was another billion-dollar project by the time it was completed in 1959. These locks near Cornwall, Ontario, give some idea of the magnitude of the task of bringing ocean freighters to the heart of North America.

Further. On the eve of abandoning power in 1948, he warned colleagues that he would come out of retirement to campaign against his own party if such a scheme was ever broached. Free trade returned to the freezer.

Continental integration happened anyway. One symptom was the decision by Newfoundlanders to enter Confederation in 1949. Mainland prosperity, urged by Joey Smallwood, a popular broadcaster, won out against the proud penury of independence. The United States exercised a similar attraction on Canada. Trade barriers, proudly erected by politicians from Macdonald to Bennett, suffered a rapid erosion when Canada signed the post-war General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, an attempt by the Western powers to dissolve trade barriers, a major factor in the Great Depression. Even without a tariff wall to justify a branch plant in Canada, U. S. corporations could easily justify investment in a stable and increasingly affluent market. British capital had financed the east-west axis of Canadian transportation; U. S. money since the 1920s had paid for links with the North. Bush pilots had opened the Canadian Shield to prospectors. Helicopters and remotesensing technology broadened the post-war assault. Two world wars had exhausted the rich red iron ore from Minnesota’s Mesabi Range. Since 1894, Canadian geologists had known of comparable reserves in the rugged interior of Quebec and Labrador, but access could easily cost half a billion dollars. That was too much for Canadians, but by the late 1940s, U. S. steel producers had the money and the motive. Between 1951 and 1954, seven thousand men pushed a rail line north from Sept-Iles, on the St. Lawrence River, through two tunnels and across seventeen bridges to the boomtown of ScheffervUle, 576 kilometres (358 miles) away, in the heart of the Quebec-Labrador peninsula.

For years, Canadians and Americans had debated the merits of a St. Lawrence Deep Waterway, but railway and Atlantic-coast lobbies feared competition, and they ruled the U. S. Congress. Canada could not yet afford to go it alone. Post-war prosperity and Labrador iron ore gave Canadians new confidence. In 1951, Ottawa declared that Canada would wait no longer. A year later, convinced that Canadians were in earnest and newly prodded by the Ohio steel lobby, eager for Labrador iron ore. Congress finally agreed to joint development of both the Seaway and its hydroelectric potential. The deal was struck in 1954. A good many Canadians were unabashedly disappointed: they had finally found the courage to do it themselves.

Across Canada, in developments great and small, U. S. capital financed a resource and manufacturing boom. Between 1945 and 1955, U. S. capital in Canada doubled from $4.9 billion to 10.3 bUlion, but direct investment tripled. Unlike British investors, who had generally lent their capital, Americans preferred to buy direct ownership and control. Critics, conservative and socialist, had long warned against U. S. “dollar diplomacy.” A growing minority of Canadians in the 1950s shared their alarm. The CCF could point to an impoverished, misgoverned Central America for evidence of the cost of corporate imperialism. Conservatives insisted that U. S.investment weakened Canada’s ties with Britain. In 1956, both parties finally united to resist C. D. Howe’s ultimate grand project, a trans-Canada gas pipeline, because he had turned to Texas developers for the capital and expertise.

Yet the pipeline debate of 1956 was political and partisan, not economic. No party doubted the need for a pipeline or for any other development accelerated by foreign capital. Most Canadians had known too little prosperity in the pre-war years to ask rude questions about its post-war sources. The articulate professionals who guided the Liberal government had little patience with economic nationalism. Politicians knew that economic growth is a fertilizer for votes. Workers claimed that U. S. employers often paid better wages than their Canadian counterparts. The 3,700-kilometre (2,300-mile) pipeline was quietly and profitably completed from Burstall, Saskatchewan, to Montreal, Quebec, in October 1958.

The general prosperity deflected attention from regions and industries left out of the post-war boom. Crippled by a shift to oil and natural gas, coal mining on both coasts and in Alberta slid into a near-terminal decline. Europe could no longer afford to import Canadian cheese, beef, bacon, or apples. There was no longer an Empire to serve as a protected market for Canadian-made cars, although a growing domestic market as a result of affluence at home concealed the loss of Canada’s greatest pre-war industrial export. Distances and the lack of dollars overseas sent more and more Canadian exports to the United States. U. S. tariff walls barred most manufactured goods, but it was usually possible to bore a loophole into U. S. markets for Canadian newsprint, lumber, or nickel. After 1952, trade surpluses vanished, but a flood of U. S. investment dollars kept Canada solvent and certainly more comfortable than Canadians had ever been in their history. In 1911, the first census questions on income had revealed that most Canadians earned too little to pay for the essentials of life. The same was true in 1921, 1931, and 1941. The 1951 census showed that Canada’s poor were now a minority; by 1961, poverty was the state of only 15 per cent of Canadians.

A contented people knew whom to thank. On November 15,1948, having carefully outstayed Sir Robert Walpole as the longest-serving prime minister in any British parliament, Mackenzie King finally retired. Chosen on August 7 by a Liberal convention, the new party leader, Louis St. Laurent, had waited for three months in an awkward limbo. A leader at the Quebec bar, born into a French-lrish family of shopkeepers in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, St. Laurent had brought intelligence, foresight, and a wholly unexpected world vision to Ottawa in 1941 when he was summoned as a raw replacement for King’s alter ego, the late Ernest Lapointe. As Minister of Justice in 1942, he had braved the divisive English-French conscription issue and survived. Inveigled reluctantly into a post-war political career on the promise of running External Affairs, St. Laurent had become the only obvious successor to King. In turn eloquent, avuncular, cautious, and shrewd, he managed Canada’s business with the dignified restraint of a good lawyer. His qualities only strengthened a decision that many Canadians had probably already made when they went to the polls in 1949. Instead of the grudging endorsement King had gained in 1945, St. Laurent won the most lopsided majority of any Parliament since Confederation: 193 Liberals to only 41 Tories, 13 ccf, and 10 Social Credit.

Four years later, there was no strong reason to revise the mandate. Post-war prosperity had easily absorbed the burdens of an impoverished province of Newfoundland, a massive Cold War rearmament, and an unprecedented baby boom. Never had prosperity lasted so long and, had it stumbled, there was unemployment insurance, even for fishermen in their seasonal layoffs. With such Liberal accomplishments in place, what new promises were needed? For the Liberals in 1953 the loss of only twenty seats, neatly distributed among the opposition parties, was hardly more than a reaction against excess. Prosperity made a Liberal government seem immortal.

World History

World History