There is no indication that Elizabeth herself ever had the faintest idea about what was going on in Ireland, but the ‘Irish Problem’ was apparent to her advisers from the start. That problem was, as the ‘Device for Alteration of Religion’ pointed out, that:

Ireland also will be very difficultly stayed in their obedience, by reason of the clergy that is so

Addicted to Rome.

Since the 1530s, traditional Irish Catholicism had been driven, thanks to the English Reformation, into a potent alliance with incipient Irish nationalism. Elizabeth realised, of course, that royal authority was under threat. No Tudor was slow to detect treason. But whether she could appreciate the situation in anything other than the crude polarity of obedience and rebellion is unlikely.

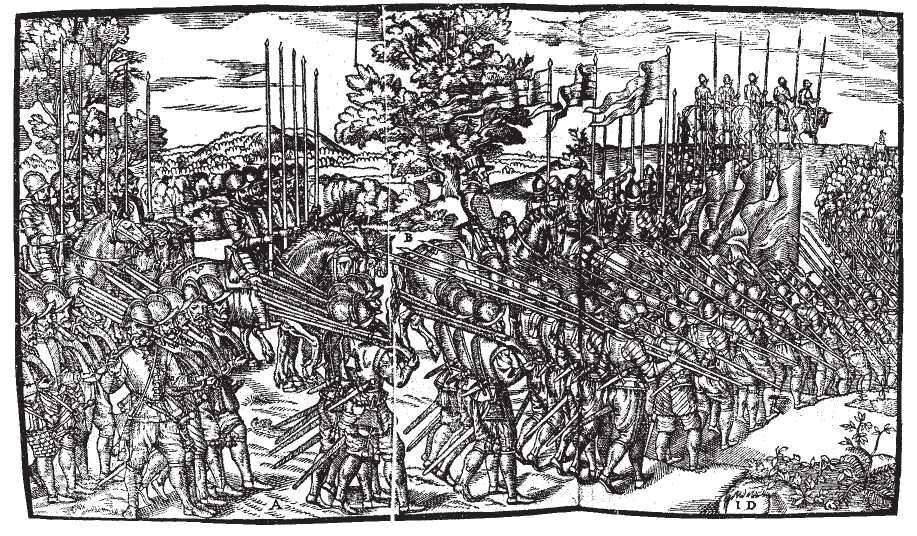

English troops campaigning in Ireland during the sixteenth century. Protestant England feared Catholic Ireland would be used as a ‘back door’ by European Catholic powers. Signs of Irish rebellion were confronted with great force. The mainland authorities instigated a policy of Protestant ‘plantation’ areas in Ireland, of which the plantation of Ulster (1608-11), largely populated by Scots, was the most effective.

What was going on in Ireland was the familiar interaction of politics and religion which dominated Tudor politics in general. But whereas the strength of personal monarchy smoothed the path of the Reformation in England, and in Wales patriotic affection for the Tudors combined with aspirations for a share in the security and spoils of the Tudor regime to the same effect, in Ireland almost everything was against the Reformation from the start, or rapidly turned out that way. English authority had never reached far beyond the Pale, and even within it the Tudor regime faced increasing problems, often because of mismanagement. While the royal supremacy was accepted relatively easily, the dissolution of the monasteries had been only partial. Irish religious orders, many of them inspired by ‘observant’ ideals of renewal, proved more durable than their English counterparts - although their survival was itself as much to do with the distance and ineffectiveness of royal authority as with any innate moral qualities of the Irish monks and friars.

As for the Protestant Reformation introduced under Edward VI, this never became law in Ireland. And when the zealous English Protestant John Bale was made bishop of Ossory (an appointment which confirms that the Duke of Northumberland had a keen sense of humour) and put on one of his violently anti-Catholic plays, he was unceremoniously hounded out of town (and, when Mary came to the throne, out of the island and the queen’s realms). The restoration of Catholicism under Mary (to the extent that it needed to be restored, which was not far) relieved the Irish from only one of the irksome restraints of English rule. The attempt to use privately funded colonisation, rather than publicly funded conquest, as a cheap way of exporting English political and social culture to Ireland was actually begun in Mary’s reign. The fact that the new colonies and boroughs of the ‘plantations’ specifically excluded native Irish people meant that the process was all too obviously being conducted at their expense rather than for their benefit.

Elizabeth’s sole initial concern with Ireland was to introduce the Protestant Reformation there. But the Reformation which was carried through the Dublin Parliament early in 1560 by the Earl of Sussex, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, was being sown on untilled ground, and found it hard to put down roots. Much of Ireland was entirely outside English control, though none of it out of reach of English punitive expeditions. Ireland was a perpetual drain on English resources. Elizabeth was never prepared to put in the kind of money which might have sufficed to introduce the English model of government to which English policy aspired. It is doubtful anyway whether England actually had the resources which would have been needed for the job. The aims of policy were variously to prevent and suppress rebellion, and to keep out or expel foreign powers. The overriding priority was to prevent Ireland from becoming a threat to England. At times, notably in the 1590s, even this modest objective required funding on a huge scale.

As Anglo-Spanish relations deteriorated in the 1570s, Philip II looked to foment unrest in Elizabeth’s backyard. It was a small force of Spanish and Italian mercenaries which sparked off the rebellion of the Fitzgeralds of Munster in 1579. The rebellion was largely defeated within a year, but the English troops ravaged the province for

English troops on the march in Ireland. The Irish found little mercy at English hands. Lord Deputy Grey boasted of how, in his two years in Ireland in the early 1580s, he had executed nearly 1,500 Irishmen of some rank, besides ‘innumerable’ churls.

Years before capturing and killing the head of the Fitzgeralds, the Earl of Desmond, in 1583. When, in the 1590s, weak government by successive Lord Deputies fuelled the ambition of the Earl of Tyrone and he launched a rebellion, Philip II was once more ready to assist. The English government was cornered into seeking the military reduction of the entire island. This reluctant conquest was eventually achieved early in 1603, thanks to the efforts of Elizabeth’s last Lord Deputy, Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy. Elizabeth’s problems with Ireland were at an end, but English problems with Ireland were barely beginning.

World History

World History