The Emergency Banking Act of 1933 was the first piece of New Deal legislation enacted to strengthen the nation’s banking system. When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, more than 5,000 banks had failed since the beginning of the Great Depression, and banking operations had been suspended by most states to prevent panicked depositors from making withdrawal demands that would shut down still more banks. The banking system was paralyzed—and it faced collapse.

During the “interregnum” between Roosevelt’s election and his inauguration, Congress and the Hoover administration had unsuccessfully sought remedies for the banking system. Toward the end of the Hoover presidency, Hoover contemplated an executive order declaring a national banking “holiday” to close the banks to protect them from runs, but refrained from such action without Roosevelt’s support. Roosevelt refused to give such an endorsement, maintaining that he had no authority (and clearly wanting no responsibility) until he became president. Hoover’s and Roosevelt’s advisers nonetheless worked together toward finding a solution. On March 5, the day after his inauguration, Roosevelt authorized two proclamations: the first called Congress into a special session on March 9; and the second, drawing on documents earlier prepared for Hoover, suspended transactions in gold and declared a national banking holiday from March 6 to March 9. Later, Roosevelt extended the banking holiday until March 13.

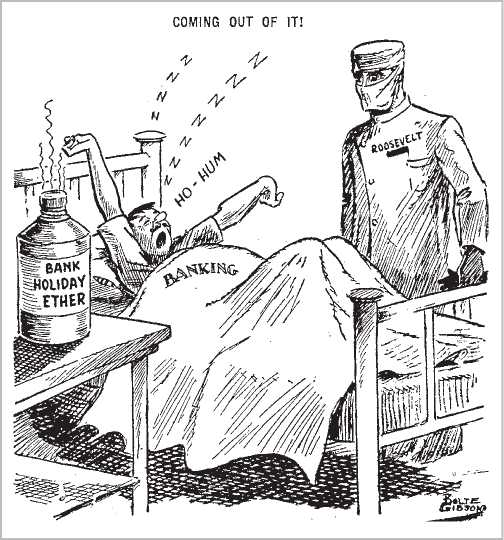

The "banking holiday" extended the influence of the federal government on the U. S. economy. This cartoon expresses the hope that American banks would come out of the holiday refreshed and revitalized. Cartoon by Bolte Gibson (Library of Congress)

On March 9, following round-the-clock meetings at the Treasury Department, FDR submitted to Congress the Emergency Banking Bill, drafted in substantial part by Hoover administration officials. Because printed copies of the bill were not immediately available, the bill’s provisions were read to the House of Representatives, which passed the bill by unanimous voice vote. The Senate overwhelmingly approved the bill a few hours later, and that evening, just eight hours after the bill was introduced, Roosevelt signed the Emergency Banking Act into law.

The Emergency Banking Act permitted the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to purchase preferred stock of banks that were in trouble but basically sound in order to put needed money in their hands, authorized issuing new currency, and took the nation off the gold standard. It also provided for the reopening of banks that were deemed financially stable by federal examiners and for the reorganization of others. On the evening of Sunday, March 12, in the first of his EIREside chats, Roosevelt told the nation that it was safe to return money to banks. On March 13, eight days after FDR’s inauguration, deposits exceeded withdrawals in the first reopened banks. The banking system had survived the crisis.

In one sense, the Emergency Banking Act was profoundly conservative, for it did not nationalize the banks or implement far-reaching new government power over the banking system. Rather, it enabled the government to shore up the existing system. Subsequent legislation would bring real reform. But the act was, together with Roosevelt’s public reassurances, remarkably effective in meeting the emergency of early March 1933. Understandably, although with exaggeration, Raymond Moley, a member of the president’s famous Brain Trust, would say later that “Capitalism was saved in eight days.”

See also Banking Act oe 1933; Banking Act oe 1935.

Further reading: Helen M. Burns, The American Banking Communi-fy and New Deal Banking Reforms, 1933-1935 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1974); Susan Estabrook, The Banking Crisis of1933 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1973).

World History

World History