(1868-1963) scholar, writer, civil rights activist A writer and sociologist, DuBois was a leader in the African-American struggle for racial equality and social justice. Although his political and social views evolved over time, DuBois consistently struggled to win access to America’s economic riches and political rights for African Americans. He is perhaps best known for his dispute with Booker T. Washington over the proper strategy for winning civil rights. In this dispute, DuBois rejected Washington’s conservative policies and argued that confrontational strategies were needed. The height of his influence came in the years stretching from 1909 to 1934 when he used his position as editor of the Crisis, the journal of the National Association FOR the Advancement of Colored People, to further the African-American civil rights struggle.

DuBois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He graduated from Fisk University and went on to do graduate work at Harvard and the University of Berlin. In 1895 he became the first African American to earn his doctorate from Harvard and wrote his doctoral dissertation, which was later published as Suppression of the African Slave Trade in the United States, 1638-1870 (1896). After teaching at Wilberforce College and the University of

Pennsylvania he became professor of history and economics at Atlanta University, where he conducted many important sociological studies of African-American life. In 1899, he published his influential The Philadelphia Negro, and a series of studies thereafter.

DuBois’s political and social ideals evolved throughout his life. He initially accepted Booker T. Washington’s conservative strategies, agreeing with Washington that African Americans could embrace self-help and community development and temporarily temper their demands for political and civil rights. During his early career DuBois also argued that African Americans were distinct from white Americans and therefore should seek the development of separate identities and cultures within the same society. However, as southern states enacted Jim Crow laws and disenfranchised black voters, DuBois began to distance himself from the philosophy of Washington. In his 1903 work, The Souls of Black Folk, DuBois attacked Washington over his strategy in regard to education, suffrage, civil rights, and the African-American relationship with the South.

By this time, DuBois had decided that African Americans needed “a talented tenth” to lead the struggle for civil rights. Washington’s brand of industrial education, DuBois argued, would never produce an educated leadership. He also argued, in repudiation of Washington, that African Americans should fight for immediate political and civil rights. Only through immediate and militant action could African Americans force white Americans to change. In adopting this position, DuBois rejected Washington’s belief that the future of African Americans lay in the South. DuBois argued that the Jim Crow South was not changing, and therefore African Americans should move, if necessary, in their struggle for equal rights. In making these arguments, DuBois distanced himself both from Washington and from his earlier thought. He firmly rejected segregation and the development of separate cultures that he had earlier embraced.

In 1905 DuBois helped create a practical outlet for his philosophy by helping to found the Niagara Movement. In opposition to the more moderate course of Booker T. Washington, the Niagara Movement espoused direct protests and demanded immediate civil and political rights. Washington used the influence he had built up through the Tuskegee Institute and his connections with white philanthropists to oppose the new direction of civil rights activism. By 1911 the Niagara Movement had failed. However, many of its leaders, including DuBois, became founding members of the NAACP.

During his time in the NAACP, DuBois had his greatest influence on American racial issues and politics. In 1909, he quit his job at Atlanta University and moved to New York City to work full-time for the new civil rights organization. The NAACP succeeded where the Niagara Movement had failed. Largely due to its biracial composition,

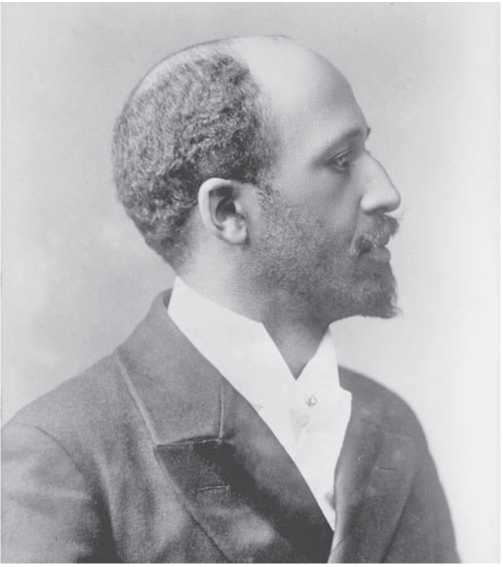

W. E. B. DuBois (Library of Congress)

It was immune to Washington’s ability to restrict the flow of funds from white donors to African-American organizations. DuBois founded The Crisis, the NAACP’s monthly journal, and used it to espouse his ideas on the issues of the day. From 1910 until he resigned as editor in 1934, DuBois used The Crisis to push a militant civil rights agenda focused on political agitation. Although he was often at odds with more conservative members of the NAACP, he managed to keep control of the content of The Crisis throughout most of his tenure.

During his time as editor, DuBois’s political and social ideals continued to evolve. He often found himself in opposition to other African-American leaders in the 1920s. On the one hand, he drew fire from more conservative NAACP leaders who did not support his militant ideals. On the other hand, he faced opposition from other African-American leaders who did not believe he was militant enough. By the early 1920s, DuBois had come to believe that socialism offered a political choice for African Americans. However, because he embraced a moderate evolutionary socialism, he came under attack from African-American leaders who believed that a more radical brand of socialism or communism offered African Americans more. DuBois also became interested in Pan-Africanism, a movement that sought to unify Africans and people of African descent worldwide, but he faced opposition from Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association.

By the end of the 1920s, DuBois had embraced Marxism as the answer to the African-American struggle. Because racism was based in maintaining the African Americans as a permanent lower class, DuBois argued, the answer to their plight was the overthrow of the capitalist economic system and all classes. Surprisingly, his interest in Pan-Africanism led him back to supporting segregation as a strategy for improving the lives of African Americans. DuBois argued that segregated schools and hospitals were better than no schools and hospitals. This rejection of the NAACP’s ideal of integration and his turn to radical politics alienated him even further from the NAACP leadership; in 1934 he resigned from the organization he had helped create. For the rest of his life, he continued to write and struggle for the rights of African Americans, but he never again achieved the prominence he enjoyed during his years with the NAACP. DuBois died in self-imposed exile in Ghana after joining the Communist Party and renouncing his U. S. citizenship.

Further reading: David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. DuBois: Biography of a Race (New York: Henry Holt,

1993); -, W. E. B. DuBois: The Fight for Equality

And the American Century, 1919-1963 (New York: Henry Holt, 2000).

—Michael Hartman and Howard Smead

World History

World History