Proposed by the Second Continental Congress in 1777, and finally ratified by all the states in 1781, the Articles of Confederation created the first national constitution. Although many have written off the Articles of Confederation as a complete failure, at the time they created a viable form of government that reflected the needs and concerns of many revolutionary Americans. The authors of the articles saw the threat of too much government as much more ominous than an excess of liberty, and thus they sought intentionally to limit the powers of the national government. Furthermore, the articles were a successful government in that they accomplished the winning of the Revolutionary War (1775-83). There were other notable achievements under the articles, including the land ordinances.

The Second Continental Congress drew up the Articles of Confederation to create a form of government for the British colonies of North America in revolt. Having convened in May 1775, Congress had begun to operate as a government. Confronted with a war, Congress raised an army and established diplomatic contacts. However, the powers of Congress were not defined, and as the war continued and independence loomed, many in Congress wanted a more formal central government that could coordinate operations, support the army, and gain allies. Congress organized a committee in June 1776 to draft a plan of perpetual union. The committee, chaired by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, worked quickly and submitted its draft to Congress within a month. The Dickinson draft actually gave the government a great deal of power, with only one serious restriction: It could not impose taxes except in relation to the post office. However, as the delegates began to debate these proposals there was immediate disagreement over how strong the government should be. Some members believed that the union should constitute only a loosely organized confederation of states. Thinking that a large centralized government would be detrimental to the people’s liberty and that power should be kept as close to the populace as possible, this group feared that a new oppressive central government was about to replace the one they had so recently left. Opponents of a strong central government held that they were not fighting a war just to exchange one form of tyranny for another. Because of this lingering fear, Dickinson’s plan for the Articles of Confederation was weakened.

The fact that the states were able to organize collectively at all was quite an achievement. The colonies had been founded separately and developed in very distinct ways. Furthermore, there had been disputes among the colonies over rival land claims. Nevertheless, the government established by the articles was not totally impotent and had considerable powers in eoreign AEEAIRs and the ability to borrow money. Article 1 gave the confederacy the

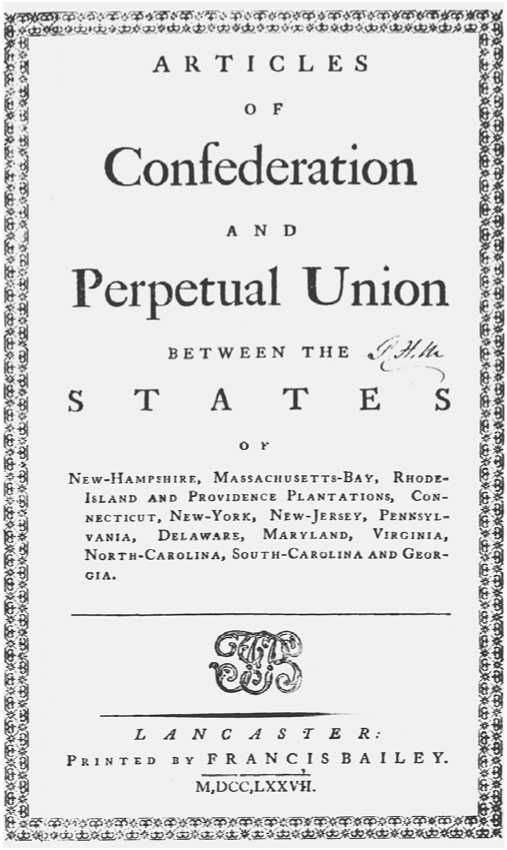

Front page of the Articles of Confederation (National Archives)

Title of “The United States of America.” Article 4 asserted that all free inhabitants of every state would be entitled to the “privileges and immunities” of every other state. This clause formed the basis for national citizenship. Article 6 forbade individual states from making treaties or alliances with foreign powers. Article 9 gave the Congress sole authority to declare wars, reconcile boundary disputes between the states, manage Indian affairs, and regulate land and naval forces. The government under the articles successfully guided the nation through war and passed the Northwest Ordinances, regulations that guided westward settlement for the next century.

While the government held some powers, there were still many weaknesses in practice. The articles more closely resembled a treaty among sovereign states, than a constitution of a united country. Each state had equal representation—one vote per state regardless of population—in Congress, and amendments required the consent of all states. There was no chief executive officer, and government departments were initially run by committees. The national government could not levy taxes on its own. Instead, states retained the power to collect taxes, and they forwarded requisitions to the United States. It was, therefore, difficult to implement laws that required funding. States often acted on their own in military affairs. Despite the provisions in the articles, some states negotiated with foreign countries and some formed their own armies and navies. Currency was another problem. In addition to the national paper bills, states printed their own paper and minted their own coins. The states retained many powers under the provisions of Article 2, which declared that each state would retain every “power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States in congress assembled.” Finally, it was almost impossible to change the articles, because amendments required the approval of all 13 states.

The Articles of Confederation were sent to the states for approval in 1777, but disputes over the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains delayed ratification until 1781. Maryland, which had limited boundaries, refused to take any action until states with large land claims ceded their western territory to Congress. When the large states ceded the lands, Maryland finally agreed to ratify. While waiting for ratification, Congress continued to operate as the government of the United States following the provisions of the unratified articles.

During the 1780s some statesmen began to argue for a stronger national government. In 1781 Congress dropped the committee system of government and created government departments headed by specific individuals. This reform streamlined government decision making. Robert Morris, the finance minister, became the de facto head of state. He sought to strengthen the national government further by advocating a 5 percent national impost on all imports. He had hoped that the measure would become law after nine states accepted it; instead, the states viewed the impost as an amendment to the articles needing unanimous approval. The impost failed when one state, Rhode Island, refused to pass it. Without the impost, and with victory in the war, the nationalist movement fell apart. Efforts to revive the impost in 1785 failed as one state—New York this time—again refused to pass the law. Nationalists had to try a different tactic, and they eventually called for changes to the articles in the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Although the articles were soon replaced by the United States Constitution, they remain important as the first government of the nation.

See also republicanism.

Further reading: Merrill Jensen, The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774—1781 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1940); Peter S. Onuf, The Origins of the Federal Republic: Jurisdictional Controversies in the United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983); Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress (New York: Knopf, 1979).

—Crystal Williams

World History

World History