Stretching back to antiquity, alchemy’s long textual tradition is largely male. With only a few exceptions, women appear in the alchemical corpus as symbolic figures, personifications of fundamental alchemical principles, not as authors or practitioners themselves. In the Renaissance, however, alchemical knowledge became accessible to a new range of people, both male and female; as a part of this expansion, a small number of women began to carve out a place as practitioners, patrons, and authors. Initially, women were most likely to participate in practical alchemical operations that verged on medicine or household tasks, such as making cosmetics and dyes. By the mid-seventeenth century, however, female alchemists began to engage in alchemy as a philosophical pursuit, taking their place alongside male natural philosophers in elucidating nature’s secrets.

Alchemy has encompassed a wide variety of ideas and practices throughout its long history including natural philosophical inquiries into the nature of metals; the production of mineral and metallic medicines; spiritual practices linking changes in matter to changes in the alchemist’s soul; practical techniques for producing dyes, artificial gemstones, and pearls; and, most famously, the transmutation of metals. In the Renaissance, practical and medicinal alchemy in particular flourished. Practitioners of all sorts took advantage of newly printed and translated alchemical texts, translations, and anthologies, as well as the market for recipes and techniques both to gain access to

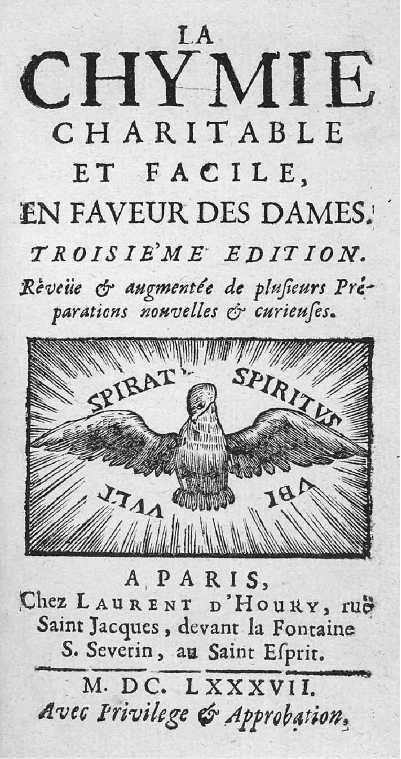

Woodcut frontispiece from Marie Meurdrac’s Accessible and Easy Chemistry for Women, published in 1666. (Othmer Library, CHF)

Alchemical knowledge and to sell their expertise in return.

Women participated in alchemy’s sixteenth-century expansion as well, though in largely private, informal ways that historians have yet to trace fully. Because there was no formal training in alchemy in universities, guilds, or colleges, women could access alchemical knowledge in the same way that most men did: by cobbling together an alchemical education from a few vernacular texts, by learning techniques from other practitioners, or perhaps by buying a recipe from another peddler of alchemical secrets. Women could also draw on their experience with traditional activities that utilized similar techniques, such as distilling water and cooking. Those who could read or whose social status put them in a scholarly milieu may also have supplemented this kind of household knowledge with a theoretical understanding of alchemical theory and practice. A very small number of women went on to use their alchemical knowledge publicly, authoring texts or pursing employment for wealthy patrons. Most women’s alchemical practice before the seventeenth century, however, remains almost invisible, documented not in printed texts, but only in letters, contracts, and other manuscript documents, if at all.

These archival traces suggest that in the sixteenth century women did participate informally in alchemy as students, assistants, or practitioners. In England, for instance, Mary Sidney, countess of Pembroke (1561—1621), was known for her interest in making medicines; although her precise involvement in alchemical projects remains unclear, she might well have joined the alchemical activities of the physicians and scholars associated with her household. In Central Europe, Duchess Sibylla of Wurttemberg (1564—1612) clearly shared her husband Duke Friedrich’s (ca. 1550—1608) interest in patronizing alchemical projects, for she signed a contract with an alchemist named Andreas Reiche, binding him to teach her and her son the theory and practice of alchemy. Women of more humble backgrounds certainly staffed some of the laboratories set up by wealthier patrons, even as servants or managers. In Bohemia, Salome Scheinpflugerin worked in the laboratory of the Bohemian magnate Wilhelm Rosenberg (1535—1592) in the 1570s and 1580s. Her fellow alchemists’ comments suggest that they accorded her a certain amount of authority in managing the laboratory. Such tiny glimpses suggest that women did participate in alchemy in Renaissance Europe, although the full extent and nature of their involvement await further historical research.

Two examples from the sixteenth century stand out: Isabella Cortese, whose alchemical secrets first appeared in print in 1561 in Venice under the title I secreti della signora Isabella Cortese (The Secrets of Signora Isabella Cortese), and Anna Maria Zieglerin (ca. 1550—1575), who worked at the court of Duke Julius of Braunschweig-Wolfenbuttel (1528— 1589) in the 1570s. Little is known about Cortese other than what appears in I secreti, where she recounted her alchemical education. She evidently learned more from her travels in central Europe than from traditional alchemical texts, which she dismissed as “only fictions and riddles” (Cortese 1561, 19).The formulaic elements in her autobiography, as well as the uncertain provenance of the book, however, make it a problematic autobiographical source; the text may initially have been a private manuscript intended for family that somehow found its way into a print shop, where it was embellished for the market. However it ended up in print, I secreti was hugely successful, appearing in at least fifteen Venetian editions and one German translation in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Cortese’s book was one of several “books of secrets” that appeared in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century, revealing practical secrets of nature that appealed to an aristocratic audience, such as how to make perfumes, cosmetics, oils, and distilled waters, as well as how to work with metals.

As the only printed book by a female alchemist in the sixteenth century, Cortese’s book was an anomaly. Although she did not publish, Anna Zieglerin did pursue her own alchemical work at the Northern European court of Duke Julius of Braunschweig-Wolfenbuttel. Zieglerin initially arrived at court with her husband, who came to work as an alchemical assistant there, but she quickly set up her own laboratory and hired at least one assistant. She also completed a short treatise, which contained recipes for a golden oil she called “lion’s blood” as well as its uses in preparing the philosopher’s stone, medicines, artificial gemstones, and fertilizing fruit trees. Zieglerin’s alchemy was particularly focused on fertility and childbirth, suggesting that she was reinterpreting male alchemists’ efforts to create an artificial human, or homunculus. Zieglerin quickly distinguished herself from the other alchemists at court (including her husband) through her connections to a mysterious adept named Count Carl, who, she claimed, not only had unique alchemical expertise but was also the son of the legendary early sixteenth-century medical practitioner Paracelsus (1493—1541). Despite initial favorable attention from the ducal court, Zieglerin and her fellow alchemists all found themselves unable to deliver on their promises (including Count Carl, who turned out not to exist after all). The male alchemists were ultimately executed for fraud and treason, while Zieglerin was executed for sorcery and adultery. These highly unusual charges against Zieglerin indicate that the Wolfenbuttel authorities found it difficult to comprehend her alchemical practice, forcing it instead into the more familiar categories of magic and witchcraft.

Cortese and Zieglerin both seem to be exceptional in that they sought a kind of publicity for their work that most women who pursed alchemy in the sixteenth century did not. In the seventeenth century, however, a number of learned women included alchemy in their scholarly pursuits. Like their learned male counterparts, Kristina Wasa, queen of Sweden (1626—1689), Marie le Jars de Gournay (1565— 1645), and Marie Meurdrac (fl. 1666) all understood alchemy as a path to the knowledge of nature and included it in their studies. Women certainly continued to pursue practical alchemical projects and to assist their husbands and brothers, but by the mid-seventeenth century they could stake a public claim to be alchemical philosophers as well.

Tara Nummedal

See also Gournay, Marie de; the subheading The Practice of Pharmacology and Laywomen (under Medicine and Women).

Bibliography

Primary Works

Cortese, Isabella. I secreti della signora Isabella

Cortese, de’qvali si contengono cose minerale, medic-inali, arteficiose, & alchimiche, & molte de l’arte profumatoria. . . Con altri bellissimi secret aggiunti. . . . Venice: Giovanni Variletto, 1561.

De Gournay, Marie Le Jars de. Apology for the Woman Writing and Other Works. Translated and edited by Richard Hillman and Colette Ques-nel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Secondary Works

Akerman, Susanna. Queen Christina of Sweden and Her Circle: The Transformation of a Seventeenth-Century Philosophical Libertine. Leiden and NewYork:E. J. Brill, 1991.

Eamon, William. “Science and Popular Culture in Sixteenth Century Italy:The ‘Professors of Secrets’ and Their Books.” Sixteenth Century Journal 16 (Winter 1985): 471-485.

Eamon, William. Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Hunter, Lynette, and Sarah Hutton, eds. Women, Science and Medicine 1500—1700: Mothers and Sisters of the Royal Society. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton, 1997.

Nummedal, Tara. “Alchemical Reproduction and the Career of Anna Maria Zieglerin.” Ambix 48 (July 2001): 56-68.

Patai, Raphael. “Maria the Jewess—Founding Mother of Alchemy.” Ambix 29 (November 1982): 177-197.

Tosi, Lucia. “Marie Meudrac: Paracelsian Chemist and Feminist.” Ambix 48 (July 2001): 69-82.

World History

World History![Stalingrad: The Most Vicious Battle of the War [History of the Second World War 38]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581864_1425486471_part-38.jpeg)