Modern understanding of ethnicity and identity has drawn heavily upon the work of the Swedish sociologist Friedrich Barth.8 Barth’s great breakthrough was to recognize that ethnicity was essentially a social construct, rather than an entity which existed independently of human action. He observed that an ethnic group was not defined by the objective biological kinship of its members, by shared language or by similarities in physical appearance as had often been assumed. All of these characteristics were strategies by which groups might identify themselves, or might be distinguished by others, but it was precisely this recognition - this acknowledgement of similarity and difference - which created ethnic identity. If the members of a group had a sense of their own unity, and if outside observers appreciated this, they could be said to have shared an ethnic identity. Signs of this group cohesion could thus be employed, consciously or otherwise, to mark this difference, whether through physical attributes, language or cultural choices. But it was the ideology of the group which defined its ethnic cohesion, not its visible symbols.

Barth and his successors also recognized that ethnicity was never fixed. The ethnic identity of groups could emerge, develop and fade in response to wider political and economic stimuli, in the manner that Procopius recognized in the Vandals.9 The symbols by which these identities were expressed also fluctuated in response to differing circumstances. If an ethnic group found itself in a precarious political position, or indeed enjoyed unprecedented power, the means by which it positioned itself with respect to other groups would inevitably change. Barth’s paradigm stressed that communal ethnic identities were in a constant process of change, and also revealed how individuals could employ different ethnic affiliations at different times. If we return to Arifridos, and speculate on his possible background, we can illustrate the principles behind these observations. If we assume from his name that Arifridos would have regarded himself as a ‘Vandal’, this would clearly have provided an important expression of his personal identity within post-Roman Thuburbo Maius. But this ‘Vandal’ identity would have meant different things when Arifridos engaged with other Vandals, with other members of the urban aristocracy or with the poorer sections of society. If we went further and suggested that Arifridos was one of those Sueves or Goths who came over with Geiseric in ad 429, and later assumed a ‘Vandal’ identity in the manner described by Procopius (there is no direct evidence for this, but his name does not exclude the possibility), the ambiguity of his ethnic identity becomes still more apparent. Among other ‘Vandals’, Arifridos would perhaps have accentuated his Suevic (or Gothic) identity; when among Romans, he would simply be a ‘Vandal’; among women, slaves or the lower classes he could have been any of these things but was also a male aristocrat. As a final point we might add that a rich female burial was found relatively close to Arifridos’ in the same church in 1912.10 Like Arifridos, this woman was buried in the gaudy jewellery popular among the late Roman and post-Roman aristocracy, which included an impressive gold necklace, a pair of gold brooches, and two earrings with inset stones. We do not know her name, and nothing apart from the general proximity of the two burials can connect her with Arifridos, but further speculation again reveals complexities inherent in the understanding of early medieval identity. If Arifridos was a ‘Vandal’, and had been married to this unknown woman since before the crossing, what might this imply about her identity? How would this have changed if she was a native of Thuburbo and had married the glamorous military aristocrat who had recently arrived in town? Or if Arifridos was the

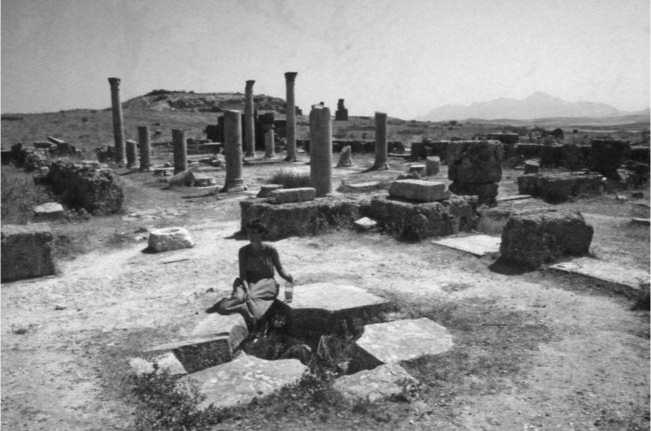

Figure 4.1 Arifridos' church: The Christian church constructed in the Temple of Ceres, Thuburbo Maius. Reproduced by permission of Professor David Mattingly

Native African and had married one of the women who had come over with the invaders? We cannot know, of course. There remains a possibility that neither of the two individuals buried in the church at Thuburbo Maius would have seen themselves as a Vandal, and a strong probability that the two were not related to one another, but the possibilities help to highlight the depth of our ignorance about the precise workings of Late Antique identity.

Studies of Late Antique and early medieval ethnicity have blossomed over the past generation and have become a major point of intellectual dispute among scholars in several disciplines, and across a wide geographical stage.11 These disputes have focused primarily upon the different means by which ethnicity might be articulated within the period, and particular attention has been paid to the importance of a sense of shared history to the evolution of group identities, as well as to the political function which new ethnic identities might have within the emergent successor kingdoms.12 The Vandals have rarely been at the centre of this debate, but the ambiguities inherent in their emerging identities make them a particularly interesting case study.13 Ethnic unity was not something that Geiseric and his followers were simply born into, but a system of social signs and behaviours which developed over time and became recognized as something quintessentially ‘Vandalic’.

World History

World History