The changes which occurred in the administration and structure of the departments of the sacred largesses (sacrae largitiones) and the private finance department (res privata) during the course of the sixth century prefigured changes throughout the whole apparatus of fiscal and civil administration which followed the drastic shrinkage of the empire in the middle of the seventh century. By the middle of the eighth century, a logothete for the general finance office (genikon logothesion) was responsible for the land-tax and associated revenues; similarly a department for military finance (stratiotikon logothesion) dealt with recruitment, muster-rolls and military pay; while another department, the idikon, or special logothesion, dealt with armaments, imperial workshops and a host of related miscellaneous requirements. The various departments which were once part of the res privata became similarly entirely independent and placed under their own officials. The public post, previously under the magister officiorum, the master of offices, became independent under its own logothete. Other departments that had originally been part of the imperial household, such as the sacred bedchamber, evolved into specialised treasuries and storehouses for particular state needs, while the bedchamber itself, known as the koiton, evolved its own personal imperial treasury for household expenditures.

While the themata, or military garrison districts and their armies, had achieved a clear territorial identity by the early eighth century, the substructures of the older provincial administration survived until the early ninth century. The dioceses disappeared, replaced in effect by the themes; but within the themes the old provincial names continue to be used for fiscal districts. Each such district was supervised in terms of tax assessment and collection by a ‘director’ or ‘manager’

- doiketes - with a staff of officials for the province and for the central sekreton or bureau at the capital. During the later seventh century supervisors ‘of all the provinces’ or ‘of the provinces’ of a particular theme appear, but after the early eighth century only individual provincial supervisors are known. By the 830s and 840s the late Roman provinces had been eclipsed by a more up-to-date structure, headed in each thema by a protonotarios or chief notary, responsible to his chief in Constantinople for running the thematic fiscal administration. Each theme had also a judge or krites responsible for civil administration and justice; and a chartoularios, responsible to the military finance department at Constantinople for the maintenance of military registers and related issues. They were all under the nominal authority of the strategos, the general, successor to the older magistri militum, but retained a degree of autonomy. This structure developed quite slowly: the old idea that the thematic general was a military supreme who was in charge of the whole thematic administration from the beginning is clearly incorrect

- this was the case probably only from the time of Theophilos (829-842). These arrangements remained in place until the late eleventh century.

Late Roman and Byzantine taxation aimed at maximising revenues. Up to the middle and later seventh century this was achieved by attributing land registered for taxation, but not cultivated, to neighbouring landlords for assessment (known as adiectio sterilium). Tax was assessed by a formula tying land (determined by area, quality and type of crop) to labour (the capitatio-iugatio system). Unexploited land was not taxed directly. Tax was reassessed at intervals, originally in cycles of five, then of 15 years, although in practice it took place far more irregularly. From the seventh or eighth centuries a number of changes were introduced. Each tax unit was expected to produce a fixed revenue, distributed across the tax-payers, who were as a body responsible for deficits, which they shared. The tax-unit (in effect, the community) was jointly responsible for the payments due from lands that belonged to their tax unit but were not farmed, for whatever reason. Remissions of tax could be requested or bestowed to compensate for such burdens, but if the community took over and farmed the land for which they had been responsible, they had also to pay the deficits incurred by the remission. Since during the same period the cities appear to have lost their role as intermediaries in the levying of taxation, this now devolved upon imperial officials in each province and upon the village community.

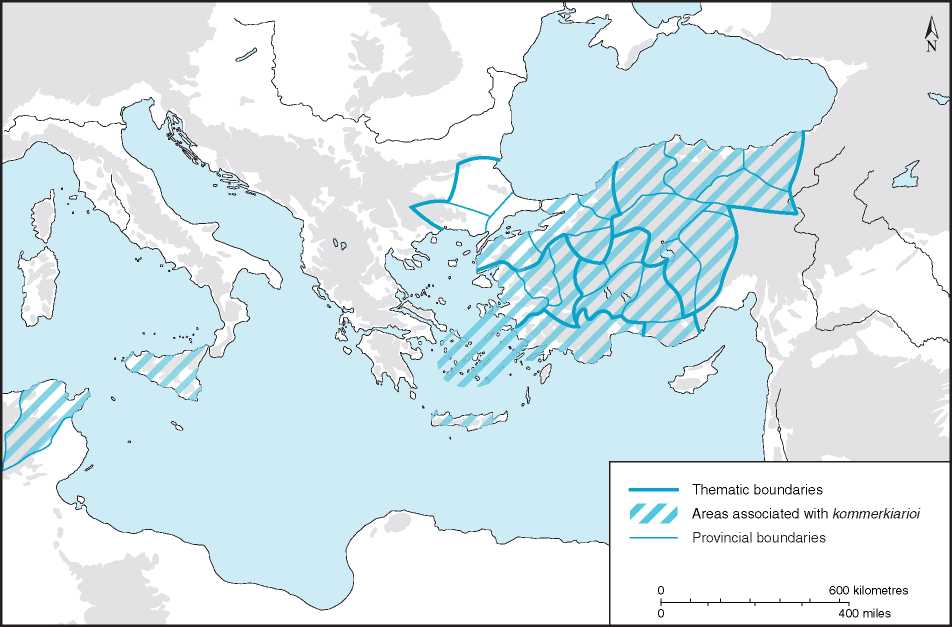

Map 6.5 Provinces associated on lead seals with general kommerkiarioi and their warehouses, c. 660-732.

The most important change which took place after the seventh century seems to have been the introduction of a distributive tax assessment, whereby the annual assessment was based on the capacity of the producers to pay, rather than on a flat rate determined by the demands of the state budget. This involved accurate records and statements of property, and the Byzantine empire evolved one of the most advanced land-registration and fiscal-assessment systems of the medieval world. These changes had been completed by the middle of the ninth century.

The regular taxation of land was supplemented by a wide range of extraordinary taxes and corvees, including obligations to provide hospitality for soldiers and officials, maintain roads, bridges, fortifications, and to deliver and/or produce a wide range of requirements such as charcoal or wood. Originating in Roman times, they continued into the middle and later Byzantine periods, their Latin names largely being replaced by Greek or Hellenised equivalents. Some types of landed property were always exempt from many of these extra taxes, in particular the land owned or held by soldiers, and that held by persons registered in the service of the public post, partly a reflection of administrative tradition, partly because they depended to a degree on their property for the carrying out of their duties. But the extra demands placed upon less powerful taxpayers complicated the system, which became immensely ramified. During the second half of the eleventh century, depreciation of the precious-metal coinage combined with bureaucratic corruption led to the near-collapse of the system.

World History

World History