A relic discovered at Antioch (mod. Antakya, Turkey) on 14 June 1098, identified by many participants in the First Crusade (1096-1099) with the weapon that pierced Christ’s side during the Crucifixion (John 19:33-34).

According to the eyewitness chronicler Raymond of Aguilers, a week after the capture of Antioch from the Turks on 3 June 1098, a Provencal peasant called Peter Bartholomew approached Bishop Adhemar of Le Puy and Raymond of Saint-Gilles, claiming that he had received a series of visions from St. Andrew during the previous months. On one of these visitations, Andrew had revealed to him the spot where the lance that pierced Christ’s side lay hidden within the Church of St. Peter in Antioch. After five days of fasting and penance, twelve men (including Raymond of Aguilers) accompanied Peter Bartholomew to the church on the morning of 14 June 1098 and began to excavate the site in search of the relic. That evening the lance was uncovered by Peter Bartholomew himself. Both Raymond of Aguilers and the anonymous Gesta Francorum report that the discovery of the Holy Lance was greeted with great enthusiasm by the crusaders, at that point themselves besieged within Antioch by Turkish forces. These same sources, as well as a letter sent by the crusade leaders to Pope Urban II on 11 September 1098, relate that the lance was carried into combat when the crusaders broke the siege of Antioch on 28 June 1098. From these accounts, it seems clear that the crusaders attributed their success in that battle to the inspiration and divine protection offered by the holy relic.

Over the following months, however, while factionalism among the crusade leaders delayed the army’s departure for Jerusalem, the authenticity of the lance was called into question, particularly by the Norman followers of Bohe-mund I, future prince of Antioch. In addition to claiming lordship over the newly conquered city, Bohemund was vying for authority over the crusade army with Raymond of Saint-Gilles, the guardian of the lance, and his southern French supporters. This situation came to a head when certain nobles and the less privileged elements of the army beseeched Count Raymond to lead them to Jerusalem or surrender the lance to those who were willing to continue the march. Raymond acquiesced and led a substantial portion of the crusaders toward Jerusalem in early January 1099. Nevertheless, a faction led by Arnulf of Chocques, chaplain to Robert, duke of Normandy, persisted in questioning the legitimacy of the relic. This situation encouraged Peter Bartholomew to undertake an ordeal in order to prove the lance’s authenticity. On 8 April 1099, Peter hazarded an ordeal by fire while bearing the lance. Raymond of Aguilers reports that Peter crossed safely between two piles of burning wood, but was mortally crushed by the thronging crowds that greeted him on the other side. Regardless of the exact circumstances, Peter Bartholomew died on 20 April 1099.

Though this turn of events did not diminish Raymond of Aguilers’s enthusiasm for the lance, it clearly contributed to the relic’s controversial status among contemporary crusade historians. Fulcher of Chartres, who was at Edessa (mod. fianliurfa, Turkey) when the lance was discovered, expressed his skepticism about its authenticity and wrote that Peter Bartholomew’s death was a clear sign of his duplicity in the matter, adding that the ordeal’s outcome greatly disheartened the bulk of the relic’s supporters.

Writing around 1115 in praise of the recently deceased Norman crusader Tancred, the chronicler Raduph of Caen excoriated both Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Peter Bartholomew for their fabrication of the supposedly holy relic. Raduph asserts that Peter Bartholomew’s demise was clear proof of the lance’s falsity. Writing from a less polemical standpoint, subsequent generations of crusade historians, including Albert of Aachen, Guibert of Nogent, and William of Tyre, present the discovery of the lance as a moment of great significance during the course of the First Crusade, but also acknowledge the controversy that surrounded the relic and its discoverer’s ordeal.

The question of the Holy Lance’s authenticity was further complicated by the existence of well-known competitors, including a lance kept at Constantinople (mod. Istanbul, Turkey) since the seventh century and one possessed by the Holy Roman Emperors since the tenth century. The ultimate fate of the lance found at Antioch is unclear. Raymond of Aguilers writes that it was carried into battle when the crusaders marched against the Fatimid-held city of Ascalon (mod. Tel Ashqelon, Israel) in August 1099, while Fulcher of Chartres comments that Raymond of Saint-Gilles kept the relic for a long time after Peter Bartholomew’s disappointing ordeal. According to secondhand sources, Count Raymond may have given the lance to the Byzantine emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, or he may have lost it during his participation in the ill-fated Crusade of 1101. If the lance dis-

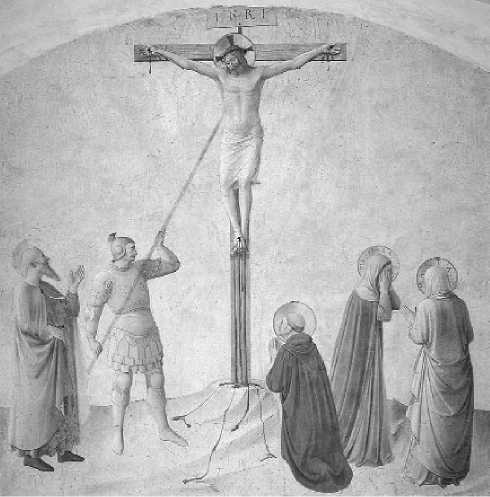

The Crucifixion with Longinus and Saints, by Fra Angelico. (Arte & Immagini/Corbis)

Covered by the crusaders did find its way to Constantinople, it may have been the same one purchased in 1241 by King Louis IX of France from Baldwin II, Latin emperor of Constantinople.

-Brett Edward Whalen

See also: Antioch, Sieges of (1097-1098); First Crusade (1095-1099)

Bibliography

Hill, John H., and Laurita Hill, Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1962).

Morris, Colin, “Policy and Visions: The Case of the Holy Lance at Antioch,” in War and Government in the Middle Ages, ed. John Gillingham and J. C. Holt (Cambridge: Boydell, 1984), pp. 33-45.

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (London: Athlone, 1986).

Rogers, Randall, “Peter Bartholomew and the Role of ‘The Poor’ in the First Crusade,” in Warriors and Churchmen in the High Middle Ages, ed. Timothy Reuter (London: Hambledon, 1991), pp. 109-122.

Runciman, Steven, “The Holy Lance Found at Antioch,” Analecta Bollandiana 68 (1950), 197-209.

World History

World History