T,

He twelfth century saw a spectacular rise of western Europe's cities. European cities had far to go to match the sophistication of such centers as Constantinople, Cairo, or Baghdad, which had populations of about 500,000, long-established trade links, and flourishing artistic traditions. But as relative peace allowed trade to expand, Florence, Milan, Venice, and Paris achieved populations close to 100,000, and another dozen cities boasted populations of 40,000 or more. It was no accident that Italian cities were in the vanguard: Italy had suffered less than lands farther north from barbarian depredations in the previous centuries and had never entirely lost the urban traditions inherited from the Roman Empire.

During the twelfth century, a new urban middle class emerged as the engineers of the cities' success. The merchants of Genoa and Pisa sent fleets to exploit the trading opportunities that had been opened up in the eastern Mediterranean by the Crusades. Venetian traders conducted a lucrative business with Byzantium, while Florentine magnates enriched themselves from the profits of the city's woolen-cloth Industry.

Along with their wealth, the merchants achieved political prominence, as the guilds established to set standards of work and to protect members' interests gradually assumed responsibility for the organization of civic life. The eagle clutching a bale of wool that appears above was adopted as the badge of Florence's guild of merchants, which, together with its sister organizations, the guild of wool traders and the guild of moneychangers, controlled the city. The nobles of Florence were forced to renounce their feudal titles and take up commercial activities before they were eligible to join the ruling council.

Under the new leadership, towns in many parts of twelfth-century Europe enjoyed a degree of social freedom and prosperity unknown to the rural laborers who toiled in the service of a feudal overlord. The cities' wealth and freedom lured thousands of peasants from the soil.

The wealth also made the city-states a target for the expansionist ambitions of both the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. Rivalries within and among the Italian cities threatened to undermine their resistance, but in the 1160s, some northern Italian cities formed the Lombard League and fought jointly to preserve their independence. Ultimately, the Lombard League succeeded in denying the authority of both pope and emperor.

¦K

I

Founded by the Romans on the north bank of the Arno River, Florence had expanded south of the river by the 1170s, when a new circle of walls was built to protect the inhabitants. Within the walls, tenements of brick, timber, and rubble were home to a teeming population of immigrants from the countryside, eager to share in the city's prosperity. Only the wealthiest families lived in relative privacy, their houses adorned with lofty towers that offered a retreat whenever the city’s fragile political stability was rent by violence.

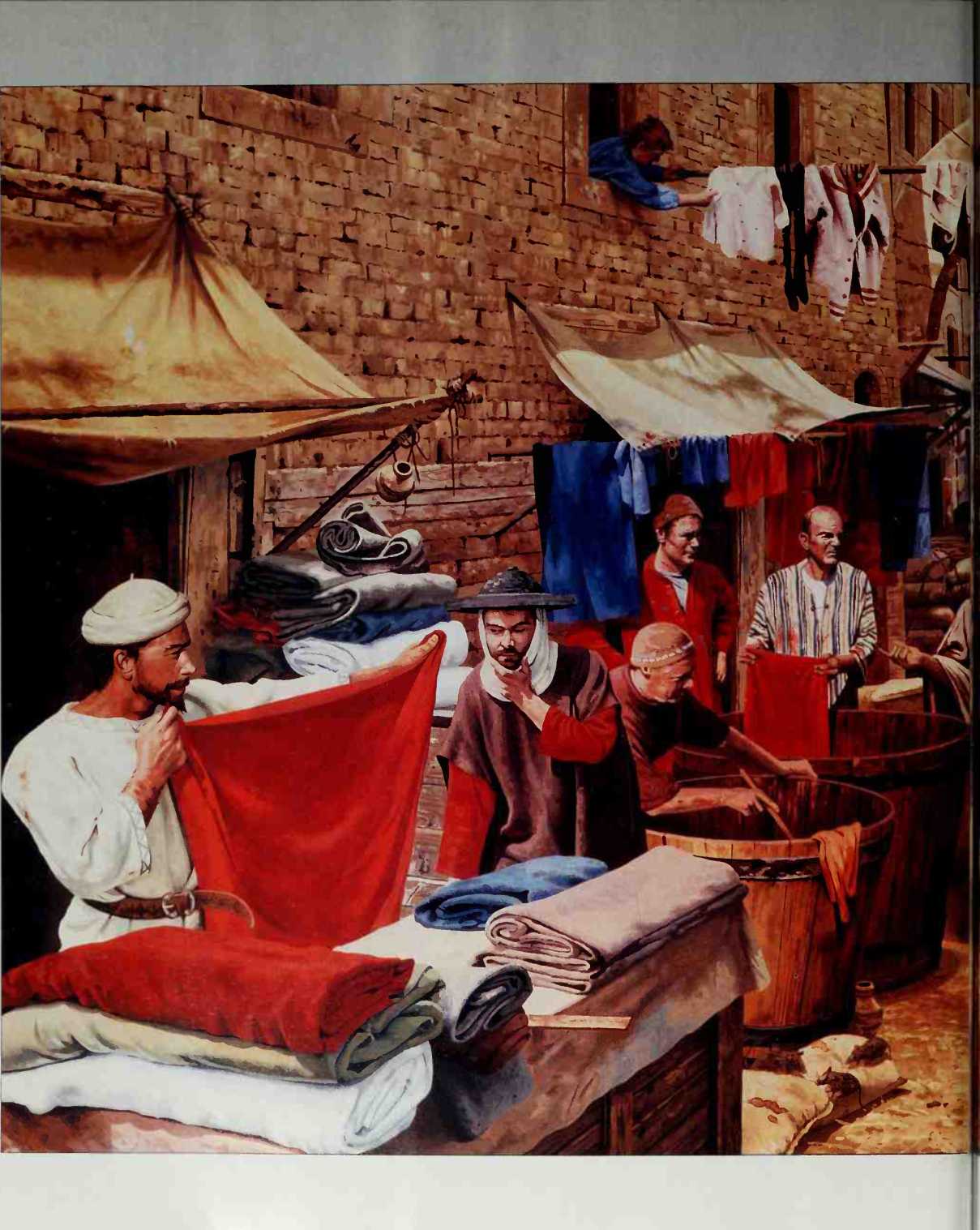

Established in the streets around the newly completed cathedral baptistry, the stalls and workshops of the cloth workers were the hub of the city's economy. By the twelfth century, Florence had established trading links throughout the Mediterranean and northern Europe, importing wool from as far away as England, Portugal, and North Africa. Brought to Italy as raw fleeces, the wool was spun by Florentine workers into thread for dyeing and weaving. The city's artisans were particularly renowned for their vivid scarlet dyes, while the quality of Florentine cloth was bettered only by that of the finest silks and velvets imported from Byzantium.

All textiles were sold by a standard measure, the braccio, which was equivalent to an arm's length. Although a few traders dealt in finished items— cloaks, breeches, and hats—most relied on the sale of unworked cloth, paid for in silver florins.

So prosperous were the merchants of Florence that they established banking houses throughout northern Europe, and it was their loans—to figures such as the kings of England and the papacy—that financed many of the wars and political struggles of the Middle Ages.

At the fairs. Moneylenders, commanding a far-flung network of agents, would facilitate the transfer of money from one country to another, relieving merchants of the dangerous necessity of transporting chests of coins along the roads. And if a merchant ran short of cash or needed backing for a new venture, it was possible to arrange for credit. All these deals were conducted with the utmost confidence. It was recognized that every agreement made in Champagne was legally binding, wherever European merchants came together.

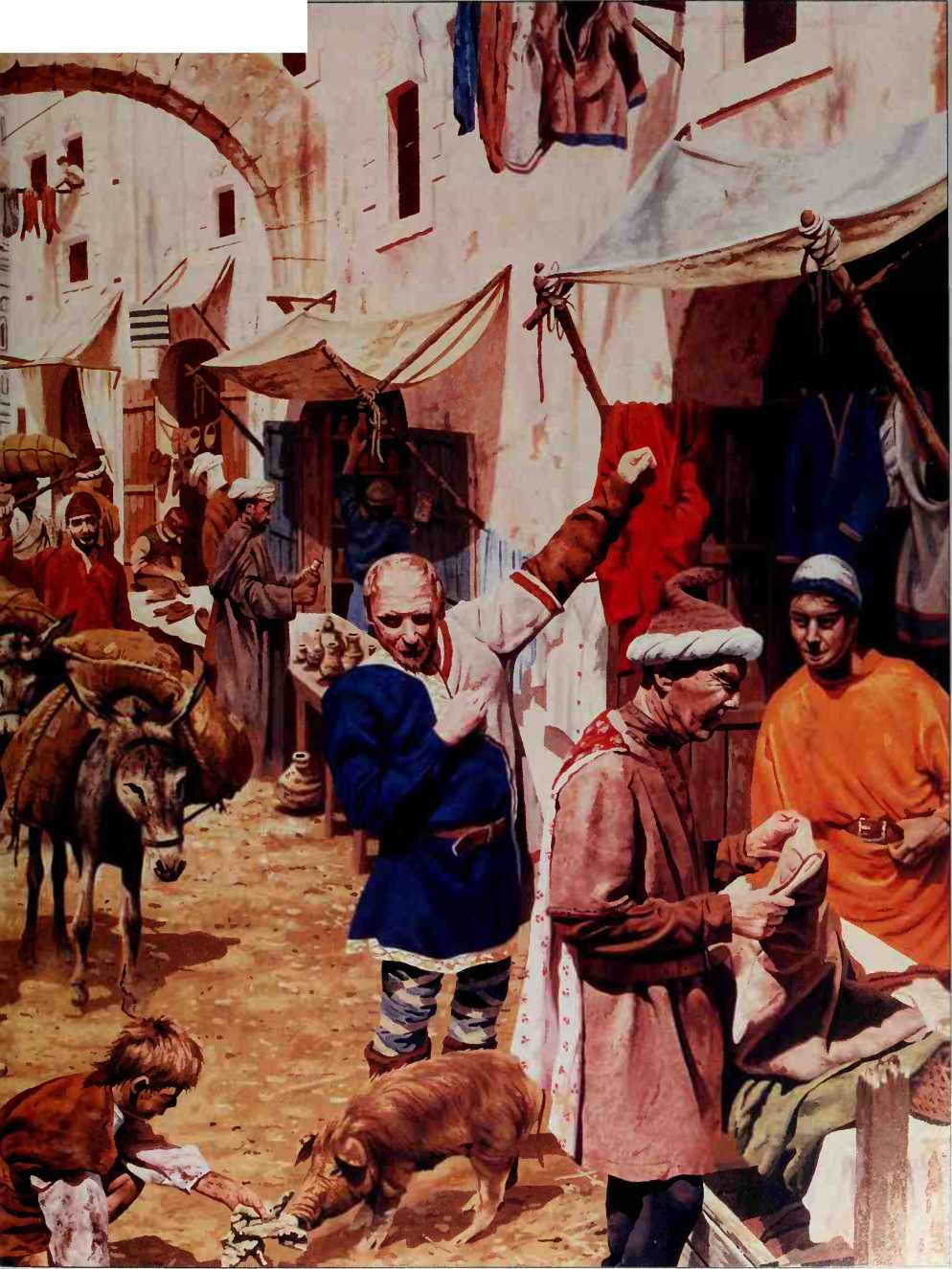

The natural habitats of these prospering merchants were the towns. The twelfth century saw many new towns created—often by royal charter—and old ones transformed beyond all recognition. Some of them became famous the world over for their wares: Milan was a byword for armor, Florence for cloth, London and Cologne for goldsmith's work. As the towns expanded and grew wealthy, they also grew in influence. Economically, politically, and culturally, the town dweller was now a force to be reckoned with.

Towns were magnets for countryfolk. For runaway serfs, the towns provided sanctuary. The Germans had a saying that "town air makes you free," since according to custom, a serf who dwelled within the walls for a year and a day was automatically liberated from his bonds. But even peasants who already had their freedom were attracted by the opportunities. New quarters of artisans' workshops and merchants' counting houses were under construction, and those able to learn a trade could be assured of gainful employment.

The urban ruling class was composed of burgesses—the merchants and master artisans who provided jobs and amassed an increasing share of society's wealth. In the early Middle Ages, the towns had fitted into the feudal system, justice and administration fell under the control of the local lord, whether a prince or a count or a bishop. But sooner or later, almost every town began to chafe under the feudal system and to seek self-government. One way to obtain freedom was to pay the lord for a charter. The alternative was to go above the lord's head to the king—who looked to the towns as natural allies against too powerful magnates. Once liberty had been granted, the townspeople quickly became accustomed to managing their town's concerns as they pleased. The burgesses were a new breed, operating outside the old system of land-based feudal relationships. They were no one's vassals, and no landlord stood between them and the king.

Nowhere was urban autonomy more highly developed than in the city-states of northern Italy. Foreign visitors, such as the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela, visiting Genoa, Pisa, and other towns in the 1160s, marveled at the freedom these communities enjoyed: "They possess neither kings nor princes to govern them, but only judges appointed by themselves."

City life in Italy had not suffered such grave damage at the hands of barbarian invaders as elsewhere in Europe. The urban tradition had carried on unchecked from Roman times. With this head start, the Italian towns were bigger than most others in Europe. Of the four western European cities with populations approaching 100,000 in the twelfth century, three—Venice, Milan, and Florence—were Italian. (Paris was the fourth.) Moreover, the gulf between town and countryside, the schisms between rural nobles and urban burgesses, did not exist here. Although the greatest part of their wealth came from trade, Italian cities were intimately meshed with their rural hinterlands. Noble, land-holding families moved into town and involved themselves in trade. Town-dwelling peasants daily walked out of the gates to tend their fields.

P.

World History

World History