Apprehension about the increasingly revolutionary character of the United Irishmen and of possible French invasion in their support prompted the passage in February 1796 of an Insurrection Act. It was made a capital offense to administer an illegal oath. The lord lieutenant was empowered to proclaim an area as disturbed and give special powers of search and arrest to magistrates in the locality. The following November the Irish parliament approved by a vote of 157 to 7 the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act.

Government fears were given validity in December when Wolfe Tone's efforts to secure French assistance saw a French fleet set sail for Ireland. Bad weather drove many of the ships out to the Atlantic so that they were unable to approach Ireland. A portion with about 14,000 men on board sailed into Bantry Bay, but the same bad weather inhibited an attempt at landing. In 1797 the government directed General Gerard Lake to undertake the disarming of Ulster, where the United Irishmen had originated and where there were many weapons stored, some dating from the Irish Volunteer period and others newly made in forges throughout the country. Despite the appeals to resist by United Irish leaders such as Henry Munro and Henry Joy McCracken, Ulster remained relatively passive during the disarming, which was often brutal. Some suggest there was a popular disenchantment with the French, whom the inhabitants still regarded as papists despite the anticlerical revolution in Paris.

In other parts of the country United Irish militancy intensified, especially as formal membership was assumed by two sympathetic members of parliament, Arthur O'Connor and Lord Edward Fitzgerald, the younger son of the Earl of Kildare. Fitzgerald, in spite or perhaps because of his aristocratic background, was an enthusiast for revolution. He quickly became the military commander of the movement. Reaction to Orange intimidation heightened popular Catholic fears and made them susceptible to Defender appeals. The militant United Irishmen did not let their secularist beliefs inhibit intensifying contacts and collaboration with the Defenders, regardless of their specifically Catholic character. Plans were made for an uprising on May 23, 1798, with expectations of French assistance.

However, the movement was replete with informers and spies. The authorities acted swiftly on March 12, apprehending a number of leaders. Shortly after they captured O'Connor and Fitzgerald. The latter was wounded during arrest and died while in prison. Martial law was proclaimed and the Militia, a regular auxiliary military force many of whose members were Catholics, and the Yeomanry, a volunteer force drawn largely from Orange Lodges, were employed to suppress the United Irishmen-Defenders and collect weapons. They were given license to use all manner of methods, including taking no prisoners, employing torture, and retaliating on whole communities, which effectively broke the back of the movement in the counties of Dublin, Kildare, and Carlow where it had been very strong.

But the reaction to what was happening in those counties had an opposite effect especially in Wexford, where general Catholic fear of a mass pogrom prompted a popular uprising in which some clergy played a central role. For a few weeks the peasant army seemed to sweep all before it, taking Wexford town and Enniscorthy and putting the militia and the yeomanry to flight. The uprising was accompanied by a number of sectarian brutalities, including the burning of a barn containing over 200 local Protestants. By mid-June 1798 the regular army had gained control of the situation, and 20,000 insurgents were routed at Vinegar Hill by Lake's well-armed 10,000 troops on June 21. Fortunately, a new lord lieutenant, Lord Cornwallis, withheld the expected vengeance. His offer of a general amnesty to rebels who would turn in their weapons brought calm to the area.

That same month the primarily Protestant United Irishmen in Antrim and Down, led, respectively, by Henry Joy McCracken and Henry Munro, rose in rebellion. McCraken led 6,000 in an abortive attack on Antrim town on June 7, and Munro's 7,000 were defeated in a battle at Ballinahinch on June 13. Both leaders paid for their efforts by being executed, as were a number of other sympathizers, as examples to other potential rebels.

Two months later, well after the back of both United Irishmen and Defender strength had been broken in Dublin, Kildare, Carlow, Wexford, and Ulster, a French force of about 1,000 men finally landed in Killala, County Mayo, on August 27 under command of General Humbert. The local peasantry looked on them as liberators and many joined them as they advanced further into Mayo. The anticlerical French Republicans were confused by the welcome accorded them by the pious Catholic Mayo peasantry. Nonetheless, the advancing mixed force prompted the defending army garrison at Castlebar, commanded by Generals Lake and Hutchinson, to flee to Tuam. The rebels established a provisional government in Connacht. However, Cornwallis was assembling substantial forces to deal with the insurgents. He was ready when he met Humbert's forces and a smaller number of local rebels at Ballinamuck, County Longford, on September 8. After a token resistance, Humbert surrendered. He and his French forces were allowed to return to France. The Irish rebels were not treated as graciously. Within the next few weeks they scattered throughout Mayo and many of those captured were executed.

On October 12 a superior British naval force captured another French expedition carrying 3,000 troops. Wolfe Tone was apprehended on the flagship, wearing the uniform of a French officer. He was taken to Dublin to be tried by courts-martial, but he committed suicide while awaiting trial, dying on November 19.

The rebellion cost Ireland at least 30,000 lives, not to mention property damage. Its failure can be attributed to a variety of factors. Foremost was the inherent contradiction between the secularist United Irishmen ideology and the traditional Catholicism of the Irish people. The natural Catholic leadership, the surviving Catholic aristocrats and the hierarchy, was suspicious of the secular United Irishmen, and most Irish Presbyterians, from among whom came most of the original support of the United Irishmen, were inhibited from supporting a movement that had so many Catholic allies, even if revolutionary. Even liberal elements within both Irish Catholicism and Irish Protestantism, especially the middle class, while sympathetic to objectives such as Catholic emancipation and parliamentary and electoral reform, had became apprehensive at the radicalization of the United Irishmen, especially the appeal to class war-

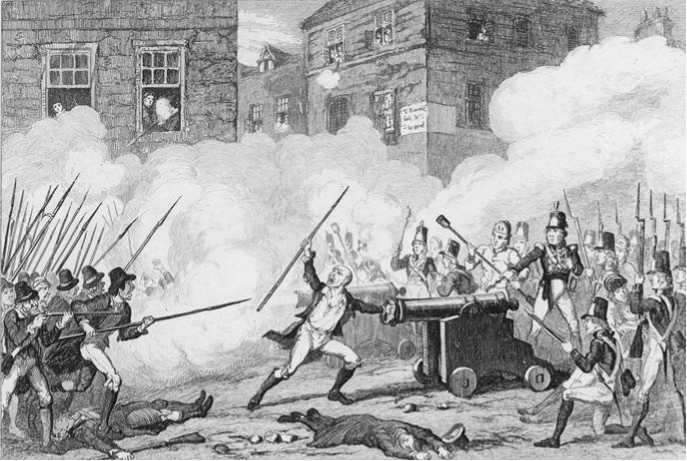

Rebels with pikes fight soldiers with rifles and cannons in the Battle of Ross, 1798. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Fare that was entailed in their approach to the Defenders. Finally, French assistance came too little and too late.

World History

World History