The Franks started building castles soon after their arrival in Outremer. In the aftermath of the First Crusade (1096-1099), those knights who elected to remain in the East probably began to build castles almost immediately. It is difficult to date these structures precisely, and the first written evidence about many of them dates from the time when they passed into the hands of the military orders or other ecclesiastical bodies. These early castles were mostly small hall keeps on two floors, like Tour Rouge (the Red Tower) in the Plain of Sharon, or taller thinner towers, like Tukhla in the county of Tripoli. They were stone-vaulted with narrow slit windows and straight stone staircases. Sometimes, as at Chastel Rouge (mod. Qal‘at Yahmur, Lebanon) in the county of Tripoli, there were outer walls enclosing a narrow courtyard with domestic offices. Seventy-five towers have been located in the kingdom of Jerusalem alone, and many more must have existed at one time. They were probably erected in the first half century of the Frankish occupation by knights who intended to settle in the rural landscape as they had done at home in the West. Insecurity and the expense of defending even these small structures meant that they almost all passed into the hands of institutions like the Templars and Hospitallers before the end of the twelfth century.

The higher nobility of Outremer tended to live in the coastal cities, where they certainly built castles. The best surviving example is at Gibelet (mod. Jubail, Lebanon) in the south of the county of Tripoli. Here the Embriaco lords of the city built a simple massive keep at the landward corner of the city walls and surrounded it with a roughly square enclosure wall defended by square towers at the corners. Nineteenth-century illustrations show very similar castles in Beirut and Tyre (mod. Sour, Lebanon). In Jerusalem the royal castle was attached to the massive Roman tower known as the Tower of David.

In more remote areas, enclosure castles were built to shelter the entire Frankish population of the district. The earliest datable example may be fragments of the hilltop castle at Montreal (mod. ash-Shaubak, Jordan), east of the Dead Sea in the lordship of Transjordan. It was erected by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1115 and enclosed by later Mamluk fortifications. In 1142 Pagan the Butler began the construction of a huge ridgetop castle to defend the town of Kerak (mod. Karak, Jordan), which replaced Montreal as the capital of Transjordan. The masonry is chunky and lacking in elegance, but the rugged strength that enabled it to defy

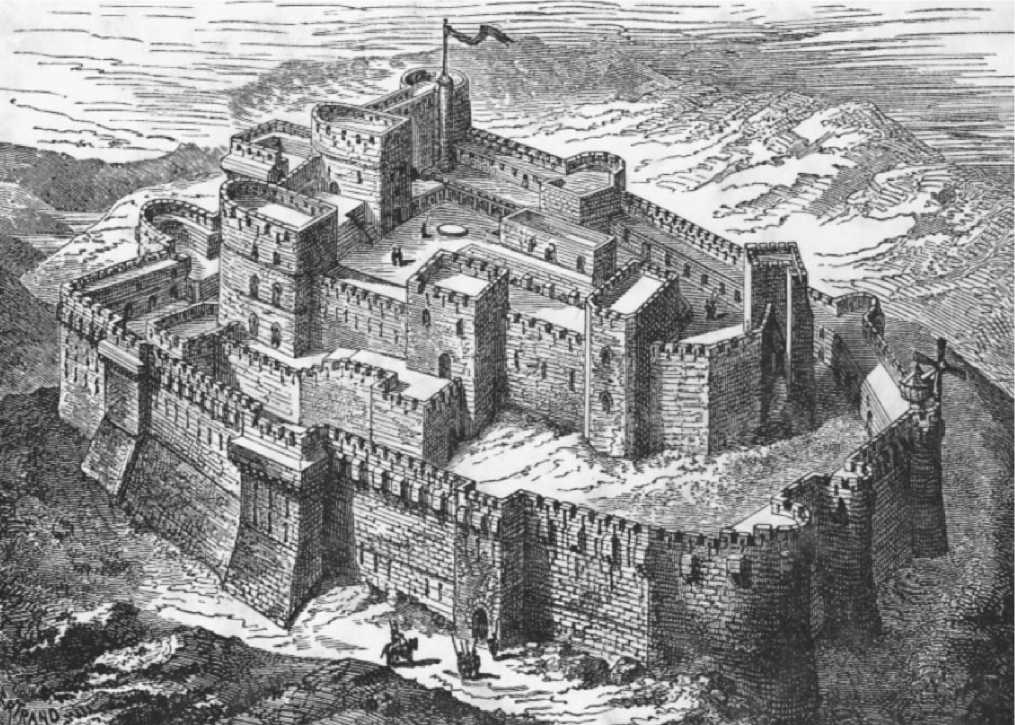

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria. (Pixel That)

Saladin’s army in 1184 is still apparent. Outposts were also maintained further south, including an amazing crag-top fortification in the heart of the ancient city of Petra. All these fell to the Muslims in the aftermath of the battle of Hattin in 1187, and both Kerak and Montreal were rebuilt and used by the Mamluks.

In the principality of Antioch, the lords of Saone (mod. Qal‘at Salah al-Din, Syria) built another ridgetop castle, cut off from the neighboring hill by a vast rock-cut ditch. The site had been fortified by the Byzantines during the tenth century, but the crusader occupants built much stronger and more massive walls and towers. Saone is really a series of large tower houses connected by a curtain wall. There are no communal buildings, apart from a vaulted shelter, which may have been a stable, and a large vaulted cistern. The fabric at Saone is of a very high standard with beautifully cut ashlars.

The military orders began to erect castles soon after their formation. Their castles were often rectangular enclosure castles rather than isolated towers or ridge fortresses. Each was in effect a fortified cloister with communal buildings, refectory, dormitory, and chapel. The rectangular or oblong enclosure with vaulted halls running along the inside of the curtain walls was the most common plan. The Templars tended to build along main routes to protect pilgrims, and few of their twelfth-century structures have survived. However, from 1168 the Hospitallers began work on a site they called Belvoir (mod. Kokhav ha-Yarden, Israel), an isolated summit commanding superb views over the Jordan Valley. The castle was destroyed by Saladin’s army in 1188, so the ruins can be fairly closely dated. It consisted of two rectangular enclosures, one inside the other, surrounded by a deep ditch cut in the rocky summit. There were large square towers at each corner of each enclosure. The upper stories

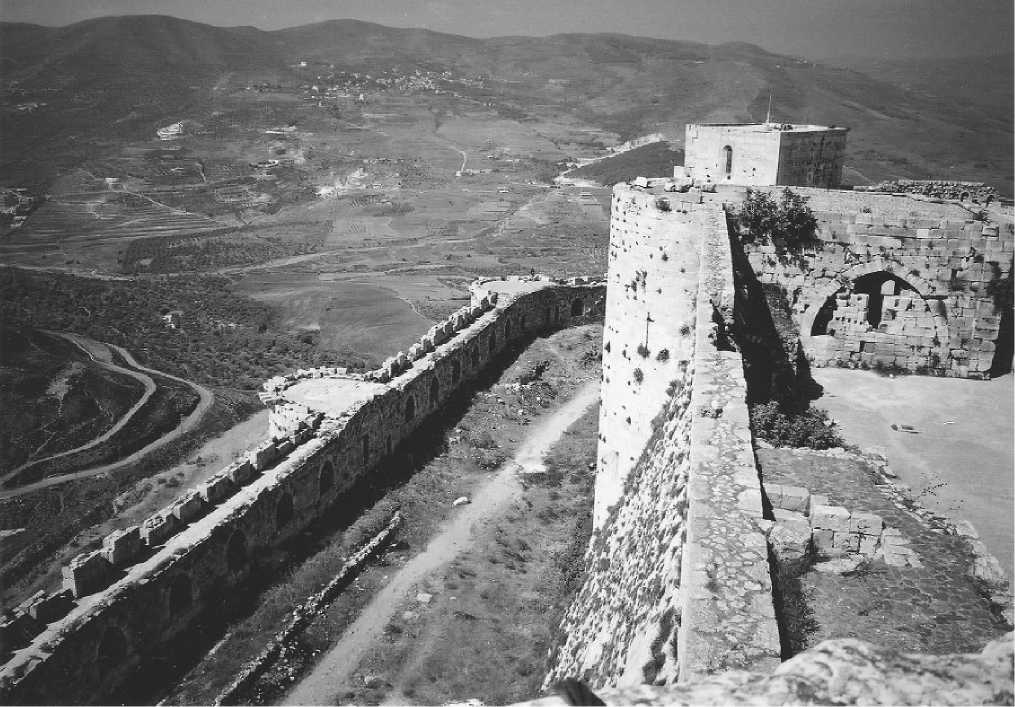

Glacis and cistern, Krak des Chevaliers. (Courtesy Graham Loud)

Have disappeared, but there must have been halls around the insides of both enclosures.

The defeat of the Frankish armies at Hattin in 1187 and Saladin’s campaigns of conquest that followed showed how inadequate the castles of the twelfth century were when confronted with an enemy who could deploy siege engines efficiently. A few castles on isolated outcrops, such as Margat (mod. Marqab, Syria) and Krak des Chevaliers (mod. Hisn al-Akrad or Qal‘at al-Hisn, Syria), were able to hold out, but most others, denuded of men and with no real hope of relief, surrendered in the end.

In the thirteenth century, the Franks rebuilt and strengthened a comparatively small number of castles, which include examples of some of the most elaborate and impressive surviving military architecture of the Middle Ages. The great thirteenth-century castles were all built by the military orders. Neither the lay aristocracy nor the monarchy, engulfed by succession disputes, had the resources needed to built credible fortifications. The builders concentrated on sites on hilltops or that had access to the sea. The castles had multiple lines of fortification, boldly projecting towers, and shooting galleries in the thickness of the walls. In many cases, they also boasted stone machicolations. Inside there were vast storerooms, halls, and places where the garrison could shelter from incoming missiles. The towers were roofed, as usual in Outremer, by stone vaults, strong enough for the mounting of trebuchets, which were often used in defense. As a general rule, the Templars used rectangular towers while the Hospitallers used round ones, although there were exceptions like the Templar castle at Baghras (mod. Bagras Kalesi, Turkey) outside Antioch. There seems to be no logical explanation for these preferences, and it may simply have been house style.

The Templars constructed a number of major monuments. In the kingdom of Jerusalem, Chateau Pelerin (mod. ‘Atlit, Israel) was constructed in 1218. As its name (“Pilgrims’ Castle”) implies, much of the labor was contributed by pilgrim volunteers. The castle stood on a promontory in the sea, and the defense was concentrated on the land side where there were two lines of wall, the inner one defended by two massive oblong towers. In the interior there were the halls typical of the work of military orders and an elegant chapel. The castle, defended by 4,000 men, survived a Muslim siege in 1220 and remained in Templar hands until it was abandoned after the fall of Acre in 1291.

Around 1240 the Templars began to build the castle at Saphet (mod. Zefat, Israel) in Upper Galilee. Virtually nothing has survived of the structure, but we have a unique account of the architecture and purpose of the castle in a treatise apparently written as a fund-raising pamphlet at the behest of the bishop of Marseilles who visited the site while on pilgrimage. Despite these efforts, the castle fell to Sultan Baybars I in 1266.

In the northern states of Outremer, or what was left of them, the Templars also embarked on major building projects. In their base in the coastal town of Tortosa (mod. Tartus, Syria), they strengthened the twelfth-century fortress by constructing a curtain wall with massive oblong towers and improving the defenses of the square keep by the addition of shooting galleries. In the court there were an elegant chapel, halls, and a chapter house, now incorporated in the fabric of the houses of the town. The most complete surviv-

Inner and outer walls, Krak des Chevaliers. (Courtesy Graham Loud)

Ing example of Templar work from this period is the tower and chapel at Chastel Blanc (mod. Safita, Lebanon). The centerpiece of the castles is a vast rectangular tower with a large simple church on the ground floor and a chamber above. This was surrounded by a curtain wall that enclosed spacious halls, but all of these are now very ruinous.

The most important surviving Hospitaller castles are to be found in the principality of Antioch and the county of Tripoli. Margat had been founded by the Mazoir family but was sold by them to the Hospitallers in 1186. Situated on an isolated plateau overlooking the coast road, the fortifications consisted of a castle town, now overgrown and ruined, and a huge citadel. Built in a rugged and unforgiving black basalt, the citadel is defended by the precipitous slopes of the hill and two lines of walls defended by round towers. At the south end where the castle site is most vulnerable, there is a massive round tower some 24 meters (781/2 ft.) in height. As usual, the court is filled with storerooms, kitchens, halls, and a large chapel. A visitor in 1212 said that the castle contained provisions for five years. Margat also contained the archives of the Hospitallers, and it was there that they retreated after the fall of Krak des Chevaliers in 1271. It was not until May 1285, just six years before the fall of Acre, that the castle was taken by the army of Sultan Qaluwun and the surviving members of the garrison were allowed to retreat to Tripoli.

Krak des Chevaliers is the most famous of all the castles of Outremer. The castle is situated on the eastern frontiers of the county of Tripoli, overlooking the plains around Homs. It passed into Hospitaller hands in the 1140s. The surviving structures seem to belong to two distinct phases. In the twelfth century an enclosure castle was built on the spur of the hill with square mural towers and halls and a chapel surrounding an open courtyard. Saladin decided it was too

Wall and towers, Saone. (Courtesy Graham Loud)

Strong to attack, but even so, in the early thirteenth century the Hospitallers thought it necessary to transform the defenses. An outer wall was built, and the inner enceinte encased by a massive new wall and glacis. Both inner and outer walls were now defended by round mural towers and box machicolations at the wall-head. A new and very elegant gothic hall was built for the knights and large, airy rooms were created in the towers.

We are told that Saphet, which was probably typical of the great castles of the military orders, had a garrison of 1,700 men in peacetime and 2,200 in war. Of these only 50 were Templar knight brethren. There were 30 sergeants, who were probably also Franks, and 50 locally engaged Tur-copoles. The remainder consisted of 300 crossbowmen, workers and servants, and 400 slaves. Castles like Krak des Chevaliers and Margat had an important offensive role. Raiding parties from the castles could set out and extort tribute from the surrounding Muslim areas. They also attracted visiting pilgrims, who would be asked to make a donation. In this way, these vast fortifications may even have paid for themselves and become moneymaking operations.

This position changed with the coming of the Mamluks under Sultan Baybars I (1260-1277). Baybars was a master of the use of trebuchets, dismantling them and moving them from one siege to another as required. Even the strongest defenses, like the south walls at Krak des Chevaliers, could not withstand these for long. Miners also contributed to the fall of castles like Margat. Two crucial facts, that there was no prospect of a relieving army and that the Mamluks offered safe conduct to those who surrendered, contributed to the fall of the castle. No castle in Outremer held out for more than six weeks after the Mamluks had begun a serious siege. The castles of the Frankish East represent some of the most developed and sophisticated military architecture of medieval Christendom, but in the

Ditch and pillar supporting the bridge, Saone. (Courtesy Graham Loud)

Absence of reinforcements and the absence of hope, they could not ensure the survival of Outremer.

-Hugh Kennedy

Bibliography

Deschamps, Paul, Les Chateaux des croises en Terre Sainte, 3 vols. (Paris: Geuthner, 1934-1973).

Ellenblum, Ronnie, Crusader Castles and Modern Histories (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Kennedy, Hugh, Crusader Castles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Lawrence, T. E., Crusader Castles, ed. Denys Pringle (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Molin, Kristian, Unknown Crusader Castles (London: Hambledon, 2001).

Muller-Wiener, Wolfgang, Castles of the Crusaders (London: Thames and Hudson, 1966).

Nicolle, David, Crusader Castles in the Holy Land, 1097-1192 (Oxford: Osprey, 2004).

Pringle, Denys, Secular Buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

World History

World History![Black Thursday [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432470149_1431513568_003514b1_medium.jpeg)