Louis IX, or St. Louis (top right), was known for his pious life and his crusading. His mother, Blanche of Castile (top left), became regent for her son when he was abroad on crusades. The author dictating to the scribe (at bottom) indicates the intellectual excitement that characterized 13th century Paris.

During the Middle Ages, local communities were important to people’s sense ofbelonging. Ifpeasants were asked to identify themselves, they would not say that they were Enghsh, French, German, or Italian. They would say that they were the son or daughter of a certain man or woman. If pressed, they would explain that they were from a particular village. In international markets, a merchant from London, Florence, Milan, or Leipzig would identify himself by his town. People cared a great deal about the community from which they came. If pressed further they would identify themselves as Christians, but the idea of having a national identity such as English, French, German, or Italian would leave them perplexed. They might identify their king or emperor and agree they owed allegiance to that person, but being part of a nation had little meaning for them.

In the 13th and early 14th centuries, people organized their communities with rules and regulations that determined who belonged to the group and who was excluded from it. Rules of behavior and membership requirements regulated trade and production of goods, education of scholars, government by councils and assemblies (either with or without the king’s approval), and establishment of everyday order in peasant communities. These groups went by different names, but they had much in common. Universitas was a Latin name that translated into “guild” in English. (It is also the root of the modern word “university.”) In the Middle Ages, it applied to students and masters who organized into groups that regulated classes and examinations as well as to guilds that organized craftsmen and merchants, setting the standards for the quality of products that members produced and rules for permitting others to join the group as apprentices. Peasant communities developed mechanisms that regulated peacekeeping within villages. The representative units that advised the monarchs of Europe went by the generic name of council, but they were called Estates in France, Parliament in England, Cortes in Spain, and diets in Germany. They might consist of only nobles and higher clergy, but increasingly they included representatives from the urban populations and successful country gentle-

Goliapdic Poems by Students

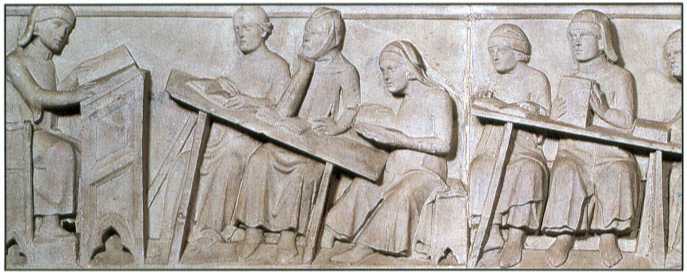

University students learned their lessons by listening to a passage from the text and then taking notes on the lecture.

Agoliard was a glutton, but the name was applied to medieval students and a style of satiric poetry they wrote in both Latin and the vernacular. Some were love lyrics, others were drinking songs, and still others concerned nature. The poem below is a begging song, in which the student could insert the name of the patron to whom he was making his appeal in the last verse.

I, a wandering scholar lad.

Bom for toil and sadness. Oftentimes am driven by poverty to madness.

Literature and knowledge I Fain would stiU be earning.

Were it not that want of pelf Makes me cease from learning. These tom cloths that cover me Are too thin and rotten;

Oft I have to suffer cold.

By the warmth forgotten.

Scarce I can attend at church.

Sing God’s praises duly;

Mass and vespers both I miss Though I love them truly.

Oh, though pride of [Normandy], By thy worth I pray thee.

Give the suppliant help in need; Heaven will sure repay thee.

Men who had made their name as administrators of the king’s justice.

The development ofcollective units was not sudden: AH of them had their roots in a variety of institutions of earlier centuries. Universities, for instance, can be traced back to the days of Charlemagne, who felt so strongly about the need to educate clergy that he ordered his bishops to establish schools at their cathedrals. Scholarship remained centered at cathedrals, but by the early 12th century, scholan and professors had begun to move from place to place, giving lectures and charging students per lecture. Lectures were delivered in Latin, the universal language of the educated. (The name of the area in which students congregated on the left bank of the Seine in

Paris is still known as the Latin Quarter.) By the early 13th century, universities were moving toward more formal structures as masters and students placed higher value on the knowledge and skills necessary to qualify for a degree. New careers in state and church bureaucracies and in business had opened for those with a university education.

Europe developed two major models for universities: the student-run professional schools such as the University of Bologna, and the master-dominated universities such as the one in Paris. By the 12th century Bologna was sufficiently famous for the study of law that Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury who opposed Henry 11, and the future Pope Innocent 111 went there for their legal training. Such students had clear career goals and wanted to ensure that the university prepared them for their chosen profession. They had already received instruction in Latin, reasoning, and mathematics but needed specific training in either canon or civil law—that is, in the law of the Church or in Roman law. Students ofcanon law studied the works of Gratian, a compilation ofpapalpronounce-ments. This law was very important because tradition made St. Peter and his successors (the popes) the keepers of the keys to heaven. Whatever laws they issued on earth, according to the Doctrine ofPetrine Succession, would also be binding in heaven. Students of Roman law studied the CodexJustinianus and the Digest, which had been prepared by Justinian’s jurists centuries earlier. Because much had changed in both canon and civil law since these works had been written, the lectures

Consisted of explanations (glosses) and updating of the texts.

In Bologna the students formed a unit/er-sitas or guild that set the standards to which professors were to adhere. To this end, the students determined the length of time that professors must lecture and the amount of text they were to cover in each course of lectures, and demanded that courses meet a set number of hours during the term and that professors not leave town without their consent. In defense, the masters formed their own guild to regulate their status within the university. They set the requirements for the exams that quahfied a person to become a master and teacher in his subjects, established fees for their lectures, regulated standards for degrees, and prescribed the dress and hoods that would distinguish them from the students.

At the University of Paris the masters’ guild dominated the students. Most of the students at Paris were working for their bachelor of arts degrees (baccalaureates) and were very young, usually between 13 and 18. Without experience in organizing their lives for themselves, they got drunk, ate irregularly, and neglected their studies while pursuing the proverbial wine, women, and song. They also fought with the townspeople over a number of issues, including high rents, unpaid bills for food and drink, crimes and property damage caused by student rowdiness, and the hostilities of townspeople who felt imposed on by the rowdy young men. A series of riots finally forced the masters to take responsibility for their young students.

As was usual in university towns, including Bologna, students were both a blessing

And a curse. Towns enjoyed profits from renting them rooms and providing them with food and drink; on the other hand, the students were disorderly. From the students’ point of view, the townspeople charged too much for their provisions and brutalized them with threats of criminal action. Whereas the sober student guilds of Bologna negotiated such disputes by the

Lady Philosophy appears to Boethius in a dream in this 15th-century edition of Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy. Adorning Lady Philosophy’s gown are the seven liberal arts that formed the core curriculum for the bachelor of arts degree: arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy, grammar, rhetoric, and logic.

Odofredus, a law professor in Bologna, outlined his lecture method when he announced his plan to give a series of lectures on the Old Digest ofjustinian: “For it is my purpose to teach you faithfully and in a kindly manner, in which instruction the following order has cus

Tomarily been observed by the ancient and modern doctors and particularly by my master.... First, 1 shall give you the summaries of each title before I come to the text. Second, I shall put forth well and distincdy and in the best terms 1 can purport of each law. Third, 1 shall read the

Text [including all the glosses done before my time] in order to correct it. Fourth, I shall briefly restate the meaning. Fifth, 1 shall solve conflicts, adding general matters and subde and useful distinctions and questions with solutions, so far as divine Providence shall assist me.”

The medieval method of teaching was for the professor and students to read a text together. The professor then explained the meaning of the text.

World History

World History