An island in the central Mediterranean, which for over two and a half centuries, starting in 1530, served as the headquarters of the Order of the Hospital, also known as the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, and, as a result of its association with the island, the Knights of Malta. The Hospitallers’ permanent presence there and the military and charitable nature of their activities succeeded in keeping the waning spirit of the crusade alive throughout the Mediterranean region, perhaps more than their operations could have ever aspired to achieve from their previous base at Rhodes (mod. Rodos, Greece). Hospitaller activity on Malta can be regarded as the last phase of the crusade movement, lasting up to 1798, when the order’s island state fell to the forces of revolutionary France.

Malta before the Hospitallers

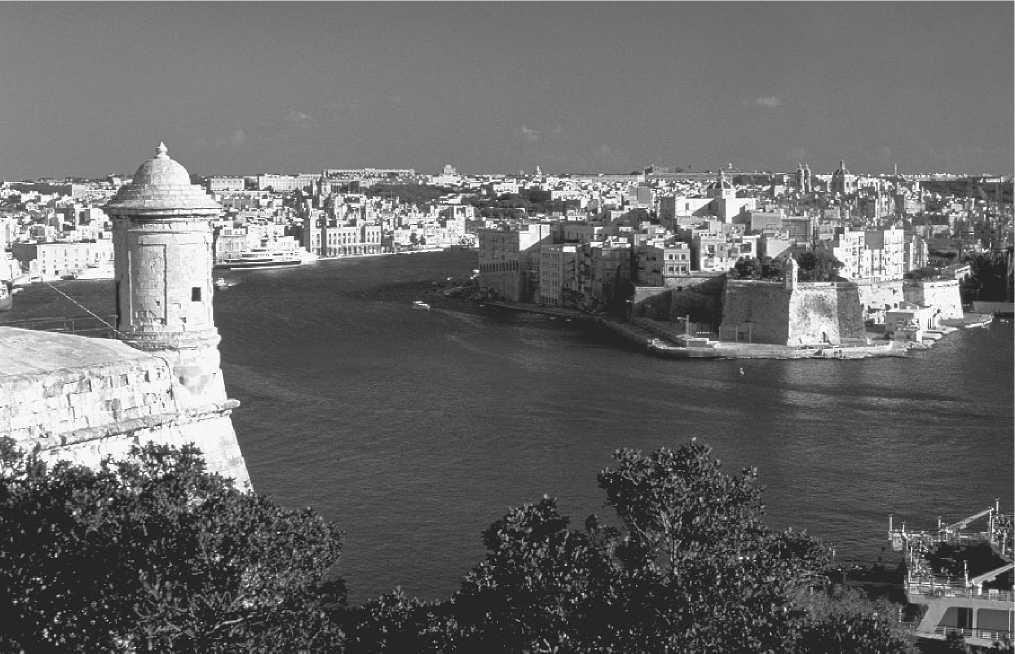

Malta’s history, which consistently reflected contemporary developments in the Mediterranean region, evolved around two major factors: the island’s geographical position, which enjoyed great strategic potential, and its deep spacious harbors, the largest of which, the Grand Harbour, was able to accommodate 300 galleys in the sixteenth century. Malta is situated at the very center of the Mediterranean Sea, some 80 kilometers (50 mi.) south of Sicily and 290 kilometers (181 mi.) east of Tunisia. It is some 314 square kilometers (121 sq. mi.) in size, the largest in an archipelago of three small islands, the other two being Gozo, 65 square kilometers (25 sq. mi.), and Comino, 2.5 square kilometers (c. 1 sq. mi.). Already inhabited by a farming community in the early Neolithic period (c. 5000 b. c.), the island has had a succession of foreign dominations, each endeavoring to exploit its natural advantages or to deny them to rivals, and each contributing to the rich mosaic of its material and spiritual culture and civilization.

It is claimed, on solid archaeological evidence, that by the time the First Punic War had begun in 264 b. c., Malta was already under Carthaginian control. However, although it was definitely under Roman possession by 218 b. c., Punic influences on the island persisted for a very long time, as evidenced in the style of surviving pottery and in the native dialect, for by as late as a. d. 60, when St. Paul was shipwrecked on the island, the inhabitants were said to have been unable to speak either Latin or Greek. As part of the Roman Empire, Malta enjoyed a modicum of political autonomy, stability, and economic prosperity, exporting olive oil, textiles, and other quality products. After an interlude during the domination of Visigoths in Sicily and the Vandals in North Africa, the island passed under Byzantine rule. The existence of several Christian catacombs or burial sites outside the Roman city of Melite indicates that the process of the Christianization of Malta had been under way by the fourth century. By the end of the sixth century, a strong Christian Maltese community with its own bishop had been firmly established on the island.

Malta’s close ties with the Greco-Roman world were abruptly severed in 869-870, when the Arabs, after a fierce struggle, captured the island, holding it until 1091. Between the major Christian victories resulting from the First Crusade (1096-1099) and the failures in the East of the Second Crusade (1147-1149), Malta was predominantly Muslim, although by this time the re-Christianization of the island had already begun. For well over two centuries from 870, whatever inhabitants lived on Malta professed a Muslim faith, practiced Muslim customs, and followed Muslim traditions. Then in 1091, precisely four years before Pope Urban II launched the crusade movement at the Council of Clermont (1095), Count Roger I, the Norman ruler of Sicily, seized Malta and terminated Arab rule. Nevertheless, Islam remained a living force on the island, with Islamic culture, in all its manifestations, surviving the first Norman conquest. This culture was such that in 1127 King Roger II of Sicily felt the need to reconquer it. Indeed, before the middle of the twelfth century, there were hardly any real traits of a Christian community there. The Muslims of Malta were ultimately expelled around the late 1240s.

With the overthrow of Angevin rule in Sicily by the Aragonese in the wake of the revolt known as the Sicilian Vespers, Malta found itself as a possession of the Catalan-Aragonese Crown. It was to this period that the island owed some of its most structurally formative experiences. These

View of the Grand Harbour on the island of Malta. (Corel)

Included the development of local government; the origins of its local nobility; the consolidation of Christian values and beliefs, partly through the emergence of religious orders on the island; and the consistent dissemination of wide Sicilian-Iberian cultural influences, which gradually superseded any surviving attitudes associated with Islam.

The Establishment of Hospitaller Rule (1530-1551)

Without constituting a complete break with the past, the arrival of the Order of the Hospital in 1530 marked a major caesura in Maltese history. When the Hospital was first set up in Jerusalem in the late eleventh century, its purpose was to care for the sick and the poor and offer Western pilgrims medical attention, food, and a temporary roof over their heads. The order gradually began to assume the complementary task of defending the routes often used by pilgrims against the Muslims. Such military responsibilities appear to have already been assumed by the early decades of the twelfth century. In 1113 the Hospital was formally recognized as an exempt order of the church. With the fall of Acre (mod. ‘Akko, Israel), the last Christian possession in Out-remer, to the Mamluks in 1291, the Hospitallers were evicted from the Holy Land. By about 1310 they had settled on the rich island of Rhodes in the eastern Aegean Sea, where they stayed for over 200 years. In 1522, a long and fierce Turkish siege drove the order out of its permanent residence in the Levant. On 1 January 1523 the Hospitallers, led by Grand Master Philippe Villiers de l’Isle Adam, along with their archives, precious relics, and hundreds of Greek and Latin inhabitants of the island, were allowed to sail out of Rhodes, never to return.

They spent nearly eight whole years without a home. Shortly after surrendering Rhodes, the grand master asked Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Spain, for Malta. After long negotiations at the imperial court, the order’s general chapter, held at Viterbo in 1527, agreed to accept Malta together with the rest of the archipelago and, reluctantly, the North African fortress of Tripoli. The deed of donation was signed by the emperor at Castelfranco (near Bologna), on 23 March 1530, and can still be seen today at the National Library of Malta in Valletta.

There were initial protests against the donation from the local universita (commune). In 1428, in reaction to the Maltese rebellion (1425-1427) against the rapacious administration of the Aragonese court favorite Gonsalvo Monroy, Alfonso V of Aragon had promised that the islands would never again be alienated from the royal domain. Charles V’s deed of 1530 was a blatant breach of that privilege, but the protests had hardly any lasting effect. With the arrival of the order, Malta’s “well-knit oligarchy of landowners, lawyers, and ecclesiastics,” as Lionel Butler defined Malta’s Universita, was soon domesticated and its powers drastically curtailed [Butler, “The Maltese People and the Order of St. John in the Sixteenth Century,” p. 145]. Those who declined submission left the country.

In 1530 Malta, Gozo, and Tripoli on the African mainland were militarily threadbare, with old dilapidated fortifications. They had very little artillery and no natural resources. Until 1551, except for necessary temporary measures, no realistic long-term policy appears to have been drawn up by the order regarding its new headquarters. In that year, large parts of Malta were looted by the North African corsair Dragut, commander of the Turkish fleet. Gozo was sacked and most of its population dragged into slavery. Tripoli was shamefully and discreditably lost.

Malta under the Hospitallers, 1551-1798

The humiliating experiences of 1551 brought the Hospitallers to their senses. The state of war in the Mediterranean demanded a completely different approach. There was no scope left either for further diplomatic maneuvering to have their convent transferred to a safer place (however temporarily), or for feelings of nostalgia for the greener and more strongly fortified Rhodes.

The order now grasped the reality of its situation. A new building program was undertaken: two forts (St. Elmo and St. Michael) were constructed; a new town (Senglea) began to emerge; and old defenses were repaired. If the events of 1551 had helped to consolidate the Hospitallers’ newly forged ties with the island, their long-term tenure was reconfirmed by the failure of the Ottoman forces to take Malta after a long, terrifying siege in 1565. In the longterm perspective of the historical development of the Mediterranean, the outcome of 1565 was not as significant as contemporaries or some later historians made it out to be. But for Christian Europe, the siege of Malta was its first great victory since the Ottoman defeat at Vienna, thirty-six years earlier. For the Knights of St. John, it was vital. As Norman Housley has pointed out, it was a clear indication that their institution was “much less isolated” on Malta in the central Mediterranean than it had been on Rhodes in the Dodecanese islands [Housley, The Later Crusades, p. 232].

For the Maltese, the defensive victory of 1565 ushered in a new era. But, for both the order and Malta, it also underscored two important social realities. First, a strong element of continuity ran between late medieval and (at least the early phase of) early modern Malta. This was the island’s dependence (sometimes partial, sometimes total) on Sicily and on whoever dominated Sicily. Secondly, although the Ottoman sultan’s savage determination to wrest Malta from the Knights did not succeed, it showed that any further attempt to regain Rhodes would definitely end up in failure.

Shortly after the siege, the Knights migrated from Birgu, where they had originally settled, to Valletta, the newly built fortress-cloister-city, a combined Renaissance masterpiece of the Italian military engineer Francesco Lapar-elli and the Maltese architect Gierolamo Cassar. The massive walls surrounding it, which were later extended to encompass the entire urban complex that grew within the harbor area, were a symbol of strength, not only against the enemies of Christ, but also against the plague. Within the walls a major hospital (the Holy Infirmary) was constructed, to which a famous school of anatomy and surgery was annexed; others were built outside. At the heart of the citadel rose a magnificent church dedicated to John the Baptist, the order’s patron saint. Other churches were erected alongside palaces, knights’ residences (Fr. auberges), and other public and private buildings. Leading foreign artists were commissioned to decorate and beautify these structures. Caravaggio was one such, as were Mattia Preti and Antoine de Favray.

In the eighteenth century a university was founded, whose origins may be traced back to the late sixteenth-century Jesuit Collegium Melitense. Codes of law were enacted to regulate everyday life in a civilized environment. The Grand Harbour, with its several wide inlets, developed into an important commercial center, with excellent market attractions and facilities. These included an incomparably efficient quarantine service, a lucrative naval base for ship repair and corsair operations, and a leading international slave market. Cotton, cumin, and ashes (the latter used for glass manufacture, soap making, as a fertilizer, and for insulation purposes, especially in hospitals) were exported on a fairly wide scale, along with other less profitable commodities.

By contrast, the rhythm of life in rural Malta remained fairly constant, except for the slow expansion of the villages, with some growing into new urban centers; the construction of large, richly decorated parish churches; and the erection of several fortified towers along the coast. There was also the pressure of a greater demand for agricultural products for a rapidly growing population. From around 20,000 inhabitants in 1530, the island could boast 50,000 in 1680, and some 80,000-100,000 in 1798. For the first time in the history of Malta, its ruling regime resided permanently on the island. It had resident ambassadors in Europe’s major capitals and consular representatives in all Mediterranean ports. European monarchies and principalities, in turn, had their own charges d’affaires accredited to the grand master’s court in Valletta, while maritime cities had consuls to look after the interests of their sailors and merchants. For the first time too, most of the revenue that flowed into Malta did not originate in nearby Sicily, but in the Hospitaller priories in Europe. This income was regularly transferred to Malta and invested there. It helped to finance all the order’s major projects and its military and charitable activities. It kept the local inhabitants in regular employment and offered them a system of social services and benefits.

Elizabeth Schermerhorn called Hospitaller Malta “the last stand of Christianity against the westward sweep of the Ottoman power through the Mediterranean” [Schermerhorn, Malta of the Knights, p. 51]. The Knights’ seasonal statutory cruises from the island to all corners of the Mediterranean, following routes stipulated by the Venerable Council, were ideally envisaged as crusading missions against the enemies of Christ; in practice, they were often allowed to degenerate into little better than profit-making expeditions against any potential prey—Muslim or Jew, French, Spanish, Sardinian, or Orthodox Greek. No wonder then that the Venetians dubbed the Knights of St. John corsairs parading crosses. In the long term, however, the Hospitallers brought to the central Mediterranean island stability and security, prosperity and confidence. They broke its late medieval isolation permanently: they succeeded in “de-Sicilianizing” important sectors of its early modern society, and they Europeanized it. They converted the island, its society, its style of life and ways of thinking into a faithful expression of baroque in all its manifestations. Under Hospitaller rule, Malta became a multicultural society, an epitome of Europe.

The End of Hospitaller Rule

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, Hospitaller Malta, like the rest of ancien regime Europe, succumbed to the powerful force of the enlightened ideas of revolutionary France. In June 1798 Napoleon Bonaparte, on his way to Egypt, sojourned briefly on the island. He aimed to free the inhabitants from the arrogance and oppression of the Hospitaller nobility, promising hope, efficiency, and benevolence. He evicted the order with hardly any resistance, and dictated the manner, based on the principles of 1789, in which the island would be governed. But Malta’s genuine aspirations and the crude realism of French politics were irreconcilable. The style of government, the new legislation, and the indecent speed with which it was implemented defied the traditional Christian values of Maltese society, contemptuously disregarded other local interests, and prompted the inhabitants to revolt. In less than three months, on 2 September 1798, the people of Malta were up in arms against the French government of General Vaubois. For the next two years, the French in Malta were under siege. The Maltese sought British aid and protection, which were generously given.

On 5 September 1800 the French capitulated. Thereafter for more than a century and a half, Malta formed an integral part of the British Empire as a major base of the Royal Navy. On 21 September 1964 it became an independent, monarchical state within the British Commonwealth. Ten years later, on 13 December 1974, it was declared a republic. Since 1934 English has replaced Italian as Malta’s second official language. The first is Maltese, a distinct language spoken by the native inhabitants and whose roots are traceable to the island’s long medieval Muslim years.

-Victor Mallia-Milanes

See also: Hospital, Order of the; Malta, Siege of (1565) Bibliography

Blouet, Brian, The Story of Malta (London: Faber, 1967). Bonanno, Anthony, Roman Malta: The Archaeological Heritage of the Maltese Islands (Rome: World Confederation of Salesian Pupils of Don Bosco, 1992).

The British Colonial Experience 1800-1964: The Impact on Maltese Society, ed. Victor Mallia-Milanes (Malta: Mireva, 1988).

Butler, Lionel, “The Maltese People and the Order of St. John in the Sixteenth Century,” Annales de l’Ordre Souverain Militaire de Malte, 23 (1965),143-148; 24 (1966), 95-101, 130-135.

Dalli, Charles, Iz-Zmien Nofsani Malti (Malta: PIN, 2002).

Hospitaller Malta, 1530-1798: Studies in Early Modern Malta and the Order of St John of Jerusalem, ed. Victor Mallia-Milanes (Malta: Mireva, 1993).

Housley, Norman, The Later Crusades, 1274-1580: From Lyons to Alcazar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Mallia-Milanes, Victor, “Paths of Power and Glory: The Hospitaller Grandmaster and his Court in Valletta,” in The Palace of the Grandmasters in Valletta, ed. J. Manduca et al. (Malta: Patrimonju Malti, 2001).

Medieval Malta: Studies on Malta before the Knights, ed. Anthony T. Luttreh (London: British School at Rome, 1975).

Schermerhorn, Elizabeth W., Malta of the Knights (Kingswood, UK: Heinemann, 1929).

Trump, David H., Malta: Prehistory and Temples (Malta: Midsea, 2002).

World History

World History