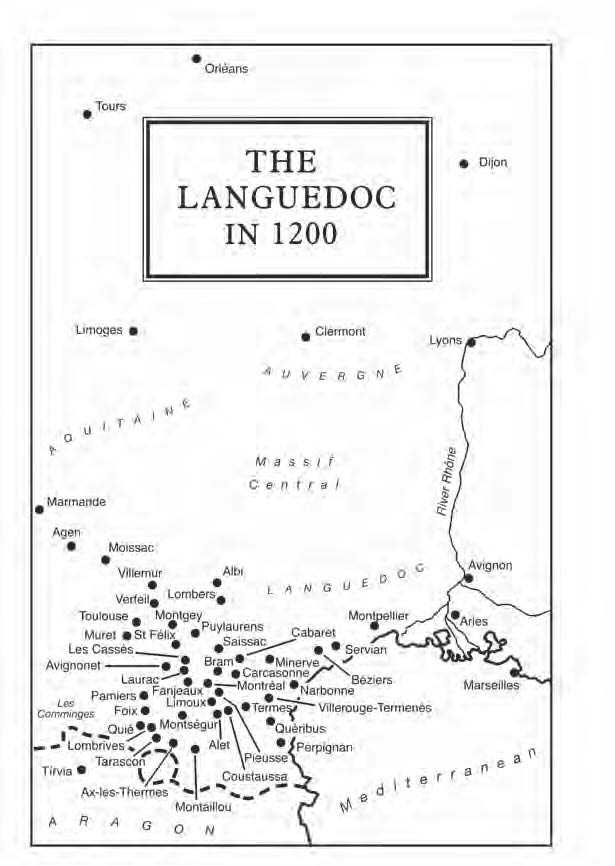

The theological showdown at Lombers was nothing compared to what happened two years later48 in the village of St Felix de Caraman in the Lauragais, south of Toulouse. The gathering of Cathars there in 1167 was ‘the most imposing gathering ever recorded in the history of the Cathars.’49 It was nothing less than an international symposium of Cathars from all over Europe, including — crucially — a delegation from eastern Europe. The purpose of the meeting seems initially to have been to reorganise the

Cathar church, and to decide on important issues such as the creation of new bishoprics, the demarcation of diocesan boundaries and the appointment of new bishops.

Presiding over the council was the still enigmatic figure of Papa Nicetas. He had travelled to the Languedoc from Lombardy in the company of Italian Cathars (more of whom later), and was evidently treated with the utmost respect. The word papa is Latin for pope, but it is not certain whether he was one of the fabled heretical Balkan antipopes so feared by the Church. In all probability, he was a bishop of the Bogomil church in Constantinople, although it has been suggested50 that he was merely a charismatic preacher exploiting western hunger for eastern wisdom. He may even have been both. We shall probably never know. What is known, however, is that Nicetas effected a profound shift in Languedocian Catharism, which would change the nature of the movement forever.

That a Bogomil bishop should be invited to chair an important Cathar gathering is the first real evidence we have of the kinship between the two heresies. While they shared numerous beliefs and practices, as we have already noted, strangely no evidence has come to light linking Bogomilism and Catharism prior to the meeting at St Felix. ‘As far as extant records are concerned,’ writes Malcolm Lambert, ‘no Bogomil was ever caught preaching [in the west], leading a group of neophytes or disseminating literature.’51 Quite how the Bogomils spread their dualist creed in the west therefore remains a mystery. Bernard Hamilton has suggested52 that heretical Byzantine monks could have spread Bogomilism while on pilgrimages

To shrines in the west, although where in the west they could have made their first landfall is open to conjecture. Palermo in Sicily seems to have had a Bogomil presence by about 1082, possibly due to Bogomils escaping Alexius’s persecution back home. Bogomilism may have had another route into Europe via returning Crusaders, some of whom could have become infected with the heresy while campaigning in the east.53 In short, we don’t know for sure. The Bogomils remain amongst the most elusive of all mediaeval sects, and the lack of firm evidence about their activities in the west gives them the air of phantoms.

Catharism had almost certainly been developing quietly for some decades before the events of 1143 brought it to the notice of the authorities, and, despite its Bogomil ancestry, was ‘never subservient to the East: as soon as we have records of its existence, it is unmistakably and thoroughly westernised and develops a life of its own.’54 The Cathar faith as Nicetas encountered it in 1167 was rapidly expanding, and used the occasion of St Felix to put its house in order. The rambling diocese of Toulouse was split up: Toulouse, Carcasonne, and either Agen or Val d’Aran became bishoprics, and the border between Toulouse and Carcasonne was settled. One aspect of the Cathar church that remained intact, however, was the process by which bishops were elected. Each Cathar bishop would have two bishops-in-waiting beneath him, known as the filius major (elder son) andfilius minor (younger son).When the bishop died, retired or resigned, the filius major automatically became the next bishop, and thefilius minor became thefil-ius major. A new younger son was then chosen. This helped maintain the unity of the Cathar church, and, in the case of the Languedocian church, helped to unify and strengthen it. Unlike the Catholic Church, there were no protracted rows about succession and election.

At some point in the proceedings at St Felix, however, Nicetas delivered a bombshell. He spoke of the unity of the eastern dualist churches, naming them as Ecclesia Bulgariae (situated probably in eastern Bulgaria or Macedonia), Ecclesia Dalmatiae (Dalmatia), Ecclesia Drugunthia (also known as Ecclesia Dragometiae, which was probably in Thrace or Macedonia), Ecclesia Romanae (Nicetas’s own church in Constantinople), Ecclesia Melenguiae (location unknown, possibly somewhere in the Peloponnese) and Ecclesia Sclavoniae (also Dalmatia, possibly another name for Ecclesia Dalmatiae). While Nicetas claimed that these churches enjoyed cordial relations with one another, they did not in fact see eye to eye on matters of doctrine. The Cathars of the Languedoc were derived from the ordo — or rule — of Ecclesia Bulgariae, which meant that they were moderate dualists. Nicetas informed his captive audience, however, that the ordo of Bulgaria was invalid, as the person or persons from whom the Cathars of the Languedoc had first been consoled had ‘made a bad end’. This was potentially disastrous news, as it meant that all the Perfect in St Felix that day were no longer Perfect. The issue was a crucial one, as the moral life of the clergy in the Catholic Church had been one of the main rallying points in calls for reform from eleventh - and twelfth-century critics, and the Cathars took some pride in the fact that the Perfect were wholly unlike the average Catholic priest in that they were actually holy; they practised what they preached, literally. To have the Perfect who had consoled you be exposed as sinful — even if it were only through a minor indiscretion — meant having to be reconsoled. Nicetas had a solution to the problem. His church in Constantinople lived by the ordo of Ecclesia Drugunthia, and he proposed that everyone accept the new ordo. There was one crucial difference between the churches of Bulgaria and Drugunthia: the latter were absolute dualists who were, in the eyes of Rome, even more dangerously heretical than the moderates. After some debate amongst themselves, the delegates at St Felix chose to accept the ordo of Drugunthia.

Catharism in Italy

As has been noted, Nicetas travelled to St Felix in the company of Italian Cathars. In Italy, as elsewhere in Europe, anticlericalism was rife. Arnold of Brescia’s campaigns against the pope only ended with Arnold’s execution in 1155, but stability did not return to the Italian peninsula. The papacy remained locked in conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor, the formidable Frederick Barbarossa, and a series of imperially sponsored antipopes. The situation was exacerbated by the influence of the Pataria, a group of pro-reform clergy who opposed the abuses of a mainly aristocratic clergy during the pontificate of Gregory VII. Like their brethren north of the Alps, the Pataria called for a morally pure clergy and remained deeply suspicious of conspicuous wealth and privilege amongst churchmen. The Pataria remained popular even after the movement’s dissolution, and the time seemed ripe for someone to step into Arnold of Brescia’s shoes.

According to Anselm of Alessandria, a thirteenth-century Inquisitor and chronicler, Catharism came to Italy from Northern France. Sometime in the 1160s, a ‘certain notary’ from that area encountered a gravedigger by the name of Mark in Concorezzo, to the north-east of Milan. Mark, evidently enthused by what the French notary had told him of the new faith, spread the word to his friends John Judeus, who was a weaver, and Joseph, who worked as a smith. Soon there was a small group of would-be Cathars in Milan, and they asked the notary from France for further instruction in the faith. They were told to go to Roccavione, a village on the road that led over the Alpes Maritimes to Nice, where a group of Cathars from northern France who followed the ordo of Bulgaria had established a small community. Mark received the consolamentum and returned to Concorezzo, where he founded a Cathar church and began to preach. Gathering followers, Mark spread the word in both the March of Treviso and Tuscany. It is probable that John Judeus and Joseph the smith also received the consolamentum, and began preaching careers. Further Cathar churches were established at Desenzano, in the March ofTreviso (also known as Vicenza), Florence, Val del Spoleto and Bagnolo (sometimes known as the church of Mantua, which was nearby).

Nicetas’s appearance, sometime prior to the gathering at St Felix, changed things in Italy. But unlike the situation in the Languedoc, where his mission had a unifying effect, in Italy he was to sow the seeds of discord. As he was to do at St Felix, Nicetas told Mark and his group that the conso-lamentum they had received was invalid, presumably as the Perfect who had administered it had also come to a bad end. Nicetas duly reconsoled Mark and his colleagues, and the group then accompanied Nicetas on his historic trip to the Languedoc. The situation, however, got dramatically worse after St Felix. Nicetas disappeared, presumably returning to Constantinople, never to be heard of again. In his place another eastern bishop appeared, Petracius from the church of Bulgaria. He informed Mark that Simon, the Drugunthian bishop who had consoled Nicetas, had been caught with a woman in addition to other, unspecified, immoralities. (Others believe that it was Nicetas himself who had made a bad end, thereby lending weight to the theory that he was something of a charlatan.) This left Mark and his group with no choice: they had to be reconsoled for the second time.

Mark set off, determined to seek a valid reconsoling, but was thrown into prison — presumably after receiving the consolamentum in the east, but before he could return to Concorezzo. John Judeus managed to speak with Mark in prison, and was reconsoled by him. However, John did not have the support of all the Italian Cathars, and some formed a breakaway group under Peter of Florence. At length, an attempt to broker peace between the two factions was made. Delegates from both sides went to the bishop of the northern French Cathars, from whom all the Italians had originated, to seek arbitration. The bishop declared that the matter should be settled by the drawing of lots, a precedent established in the Acts of the Apostles, where the disciples drew lots to elect Judas’s successor. The winning candidate should go to the east, be reconsoled, then return to Italy and proceed to reunify the Cathar church. The plan was scuppered by Peter of Florence, who, in a fit of pique, declared that he would not submit to the drawing of lots. Peter then found himself out of the running, with John Judeus seemingly the winning candidate for the journey to the east. However, some of Peter’s party were not happy with this arrangement, and protested. John Judeus, less of a primadonna than Peter, resigned, not wishing to cause further trouble.

In an attempt to sort out the mess, a council was convened at Mosio, which lay between Mantua and Cremona. The new plan was that each side would propose a candidate from their rivals. The chosen candidates were Garattus, from John Judeus’s party, and John de Judice from Peter’s. Again deferring to apostolic precedent, lots were drawn and Garattus was elected. Preparations were set in motion for his journey to the east: he started to choose travelling companions, and money was collected for the trip. Just as Garattus and his party were about to depart, however, two informers claimed that he had been with a woman. This proved to be the last straw and Italian Catharism splintered permanently. Desenzano remained faithful to the ordo of Drugunthia — and therefore Nicetas — and became a stronghold of absolute Dualism, while Concorezzo, Mark the gravedigger’s church, reverted to the ordo of Bulgaria and moderate Dualism. The church in the Trevisan march took the middle line, and sent their candidate to Ecclesia Sclavoniae, which was impartial in the dispute between

Bulgaria and Drugunthia. Unlike their counterparts in the Languedoc, the Italian churches would continue to bicker for the rest of the movement’s existence.

World History

World History