The patriarchate of Constantinople was one of the five major administrative units into which the Christian Church had organised itself territorially within the Roman world, the others being Rome, Jerusalem, Antioch and Alexandria. Constantinople was the last to be raised to ecumenical status, which it first claimed formally at the council held there in the year 381, but always contested by Rome. Each see had an apostolic tradition, and the history of their relations with one another are heavily inflected by claims and counter-claims about precedence and rights. The position of the patriarchate of Constantinople was enhanced by the fact that the city was also an imperial capital - and after 476, the imperial capital - but the Roman see never admitted Constantinopolitan equivalence. Whereas the development of the see of Constantinople thus took place in an environment which transformed it slowly but surely into an ‘imperial’ church, Rome was, with a few exceptions, in effect independent of direct political influence from the emperors. One of the results was that Rome appeared at times as an independent authority, and conflicts within the Byzantine Church could be referred to Rome, with the result that the tensions between Rome and Constantinople, on the one hand, and within the Byzantine world, between different factions within the church, as well as between the secular power and one or another of these factions, were further heightened.

Bishops typified the growing importance of the church both spiritually and institutionally within the empire. Bishops were by the sixth century recognised as key members of city governing councils; they were, as managers of church lands in their sees, major controllers of economic resources, a position they maintained throughout the history of the empire and

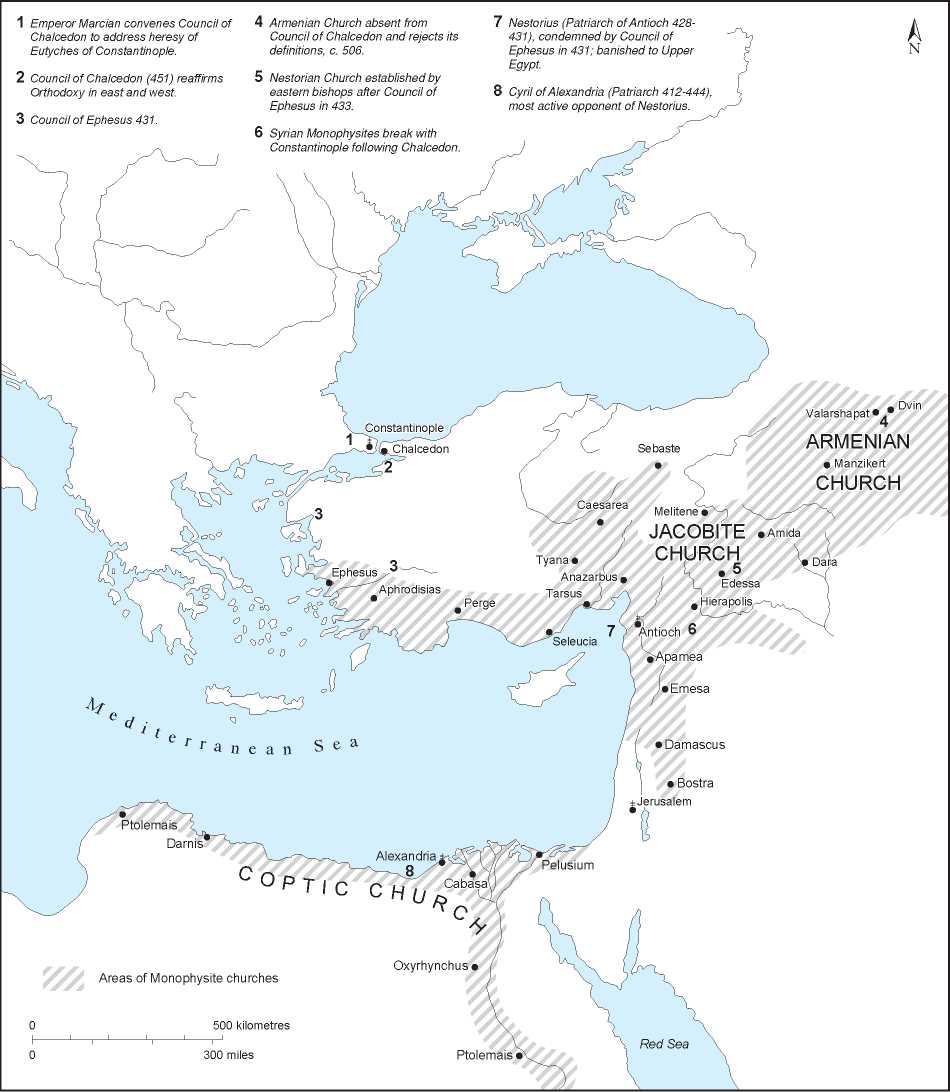

Map 4.2 Politics, religion and heresy, 5th-6th centuries.

Beyond. Such was the wealth accumulated by the church by the later sixth century that one estimate has suggested that the resources it consumed to maintain its charitable institutions, its clergy and episcopate, its public ceremonial and its public buildings were greater even than those of the state - excluding the army, of course. This wealth was mostly in land, although substantial amounts were invested in gold and silver or in

Buildings. The church derived a large income from rents from its numerous estates, whose importance was clearly understood - the canons, or laws, of the general council held at Constantinople in 692, known as the Quinisextum, included prescriptions about bishops staying in areas subject to hostile attacks in order to look after their flocks - and, presumably, church lands and property.

Charitable foundations were a major focus for the church’s philanthropic activities, but they had to be supported, and were usually funded by the rents from large estates. Orphanages, hospitals, almshouses, for example, were built and maintained, some by private persons after they had decided to endow their lands, sometimes by the church itself - the importance of the church in the state is reflected in the establishment by the emperors of various imperial charitable houses, illustrating the ideological importance of such commitments. Vast amounts of land were given to the church over the centuries, sometimes in large bequests from wealthy persons, just as often in the form of tiny parcels of land willed to the church by the less well-off. church land could not in theory be alienated - once devoted to God, always devoted to God - so that the accumulation could only grow. But in fact, the use of emphyteutic leases, by which life-long and often hereditary lease contracts were agreed, meant that land frequently did in practical terms fall outside church control and supervision.

Church administration followed the secular organisational pattern of the late Roman empire. Below the patriarch were metropolitan bishops, autocephalous archbishops, and bishops. The first was the senior cleric in each province, and was personally appointed by the patriarch. Bishops were elected by the provincial synods attended by all bishops, and until the sixth century the ordinary clergy and congregation of the region also had some influence, at least in nominating candidates. The bishop was the highest-ranking church official in his region, with both the regular clergy as well as any monastic communities present under his authority. Bishops were leaders of their communities spiritually and politically: many bishops had been martyred during the great persecutions of the later third and early fourth century, and the position of bishop was one to which considerable esteem was attached - but of which expectations were accordingly high. Bishops were based in cities, and insofar as the bishop’s jurisdiction extended over the territorium of his city, the ecclesiastical administration of the empire preserved the late Roman secular administrative pattern of the Roman world.

The task of the bishop was threefold: seek out and combat heresy, ensure that orthodoxy prevailed; and impose and apply church law. He was also the chief manager of church lands, giver of charity to the poor and needy; as well as the leading ecclesiastical authority and judge in his district. He presided over the church courts regarding clerical mores and correctness; and he arbitrated in cases involving conflicts between laypersons and the church - indeed, from the early seventh century the clergy had an especially-privileged legal status, to prevent their being mistreated at the hands of secular authorities. Bishops were generally, although by no means exclusively, drawn from the more privileged and the best-educated sections of society, at least from the middle and later fourth century.

While responsible for the physical as well as spiritual welfare of their flock, bishops tended also to share the views of the privileged elite from which they were drawn, so that those based in the provinces in particular have left letters bewailing their fate, relegated as they felt themselves to be to regions of cultural darkness and barbarism. Of course, such images are often deliberately overdrawn for effect, and many bishops and senior clergy in the provinces were thoroughly committed to the care of their congregations. Corrupt and dishonest clergy there certainly were, but there is little clear evidence of the degree of these problems.

A major concern of the church throughout the empire, and an aspect in which bishops played a fundamental role, was in public welfare: bishops were responsible within their sees for the organisation of charitable activities, in particular the relief of the poor. Such activities depended, naturally, on the commitment and involvement of individuals, so that there is no uniformity of practice across the empire. Many bishops did very little, but many also funded the construction of almshouses, hospitals, refuges for lepers, and so on. Bishops and senior clergy were also involved in politics, both secular and ecclesiastical. Bishops were often asked to speak out for particular individuals, or for certain groups in their jurisdiction - the poor peasants suffering from heavy taxation, for example, at one extreme, or the imperial official seeking redress from the emperor for political victimisation.

The extent to which bishops were successful depended largely on their contacts - their own network of connections at court and in the government - as well as on their ability to present the case convincingly, and on the context and personalities concerned. Senior clergy, bishops especially, had the right to exerciseparrhesia, ‘freedom of expression’, which they often did, particular in respect of powerful secular figures - emperors, imperial officials and so on, on behalf of their flock or in order to speak out against what they perceived as unorthodox beliefs or behaviour. This often got them into trouble, especially where a patriarch, for example, attempted to oppose a strong-willed or determined emperor in respect of some issue of state affairs or high church politics.

World History

World History