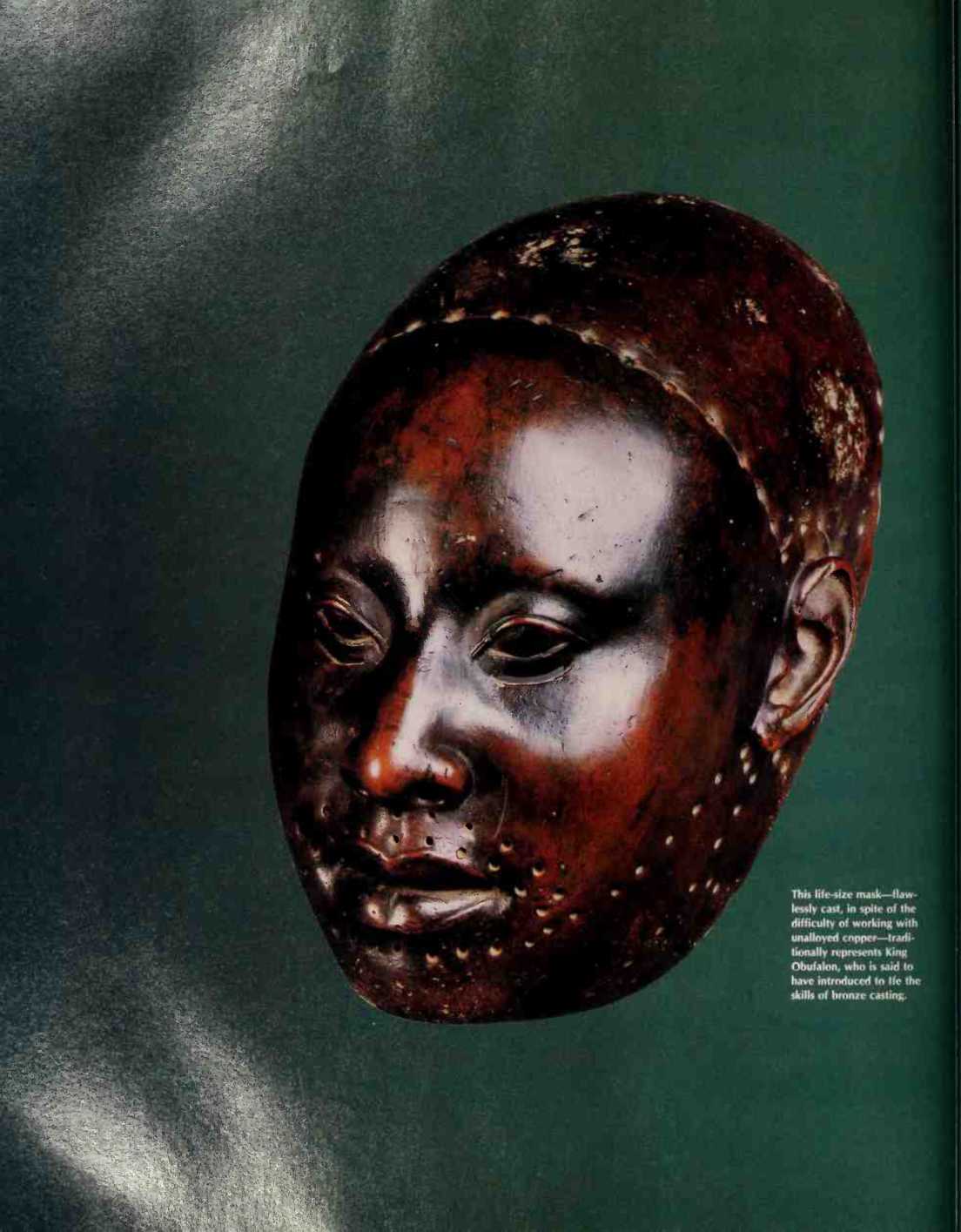

No African works of art have greater serenity arxi dignity than the life-size sculpted heads created hy the Yoruha people of Ife, a kingdom in the south of present-day Nigeria that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. The terra cotta at right and tlie copper and bronze heads on the following pages show a sensitive naturalism without parallel elsewhere at the time.

Terra-cotta sculptures of fired, unglazed clay display signs of a continuous evolution from an earlier iron-age culture located in northern Nigeria. The bronzes were produced by an intricate process known as "lost wax," which the YoruFwi F>egan to use around the eleventh century. This method involved modeling beeswax over an earthenware core, encasing this in a mold of fine clay, then heating the clay mold to liquefy and remove the wax, and pouring molten metal in its place.

The bronze heads were probably employed in the funerary rituals held for the all-powerful priestly rulers of the kingdom. The funeral ceremonies were held some time after the death of tlte kings, whose corpses were buried immediately because of the hot climate.

The holes around the statues' hairlines could have been used for fixing real crowns to the heads; similar holes around the necks perhaps enabled the heads to be fastened to wooden effigies. The bronze heads were either held for safekeeping in the Ife royal palace nr buried at known spots beneath the trees of a sacred grove, whence they were disinterred for reuse in rituals as the need arose.

Kenya; local Africans, who quickly learned about seafaring and the practices of long-distance trade from these and other foreign merchants, founded their own settlements along the coast and in northern Madagascar. But not until the late thirteenth century, following a great wave of Muslim expansion into India and Indonesia as well as eastern Africa, did these settlements come of age as flourishing centers of international trade.

The products of East Africa that attracted foreign merchants were rich and varied. Ivory, tortoiseshell, incense, and spices were staple items of trade, but ships leaving the east-coast ports also carried iron ore from the mines around Malindi and Mombasa, copper and tin from Katanga (in the southwest of modern Zaire), and gold from Zimbabwe in the south. Just as Europe's hunger for gold was fed by Mali, so the mines of East Africa supplied Arabia and India. The principal imported goods were cloth and beads, used for barter and decoration, but luxury items such as Ming porcelain from China and stoneware from Thailand testified to the wealth and sophistication of the merchant communities.

During the fourteenth century, there were more than thirty major ports along the coast, from Mogadishu in the north to Kilwa and Sofala in the south. Their African populations were skilled fishermen and farmers as well as traders, and they spoke a form of Bantu, the most widely dispersed family of languages in Africa. Out of the continuous mingling of these Bantu-speaking Africans with Arab merchants there developed a distinctive, urban-centered culture known as Swahili—in Arabic, "people of the coast." The Africans adopted the Islamic faith and incorporated many Arabic words into their own language, and Swahili became the everyday speech of all the east-coast centers of trade.

The governors of these cities built mosques, palaces, and forts of coral stone. Some were ruled by Arab sultans who ousted the local chieftains. According to an anonymous Swahili historian who wrote a history of Kilwa in the early sixteenth century, the leader of the first Arab traders to reach this settlement had purchased the offshore island from its African ruler. "The newcomer to Kilwa said: I should like to settle on the island: Pray sell it to me that I may do so. The infidel answered: I will sell it on condition that you encircle the island with colored clothing. The newcomer agreed with the infidel and bought on the condition stipulated. He encircled the island with clothing, some white, some black, and every other color besides. So the infidel agreed and took away all the clothing, handing over the island."

Some days later the African returned with his followers, intending to cross over to the island at low tide and attack the traders; but he found that the channel separating the island from the mainland had been deepened, making the crossing impassable. "Then he despaired of seizing the island and was sorry at what he had done. He went home full of remorse and sorrow."

As the largest of the southerly trading ports, Kilwa was able to obtain a monopoly of the trade in gold from the region of Zimbabwe, an inland kingdom to the south. The people of Zimbabwe were essentially cattle raisers, and the need to defend their large herds and distant grazing lands had led to the development of a centralized state under a royal dynasty. During the fourteenth century, the kings acquired new wealth from the export of gold that was mined from alluvial and reef deposits within their territory. The enormous walled enclosure known as Great Zimbabwe, constucted around the time when the gold trade was at its peak, was a vivid demonstration of the power and influence of the people of Zimbabwe.

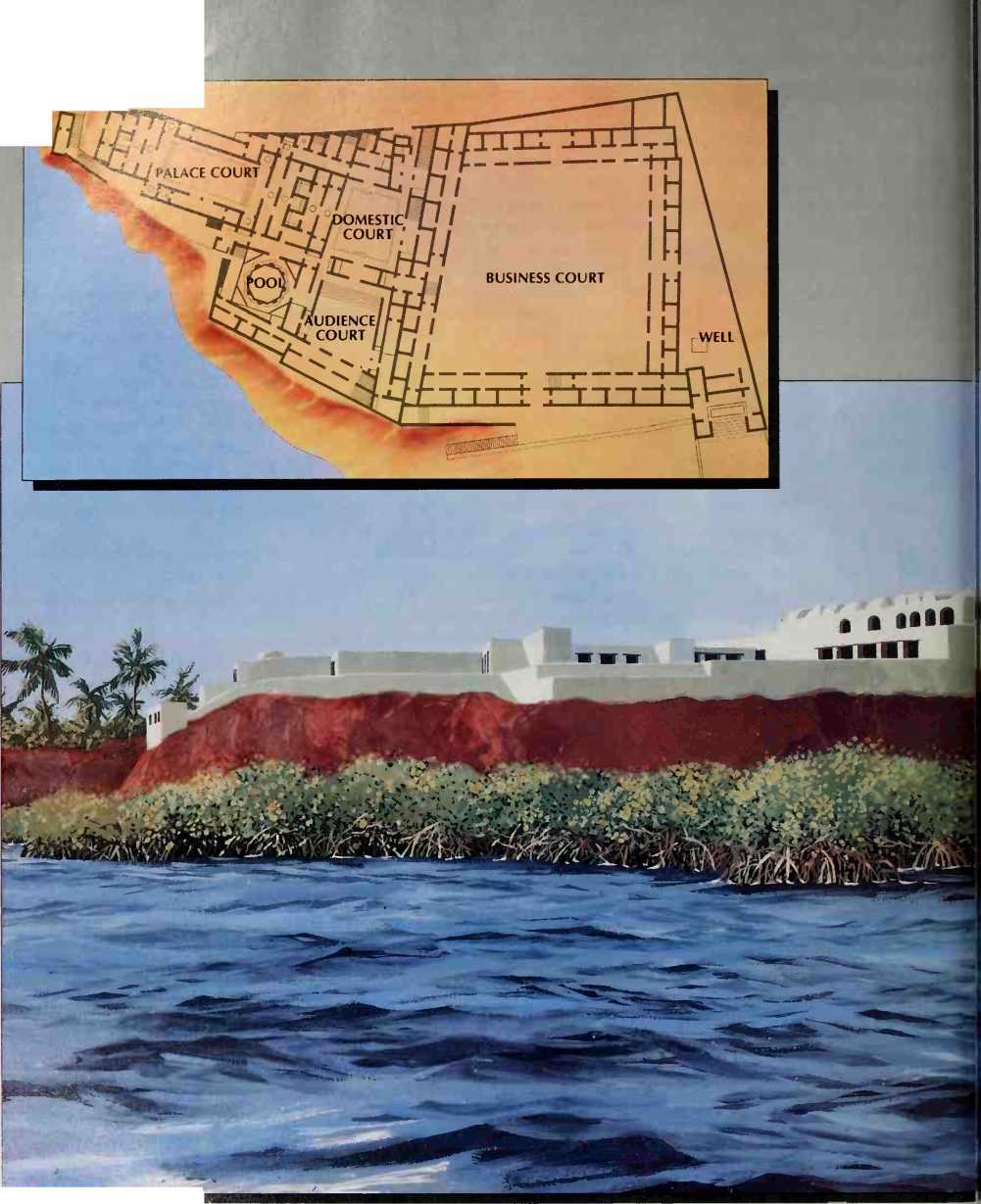

Most of the gold was carried overland to Sofala, the nearest coastal settlement, from where it was shipped north to Kilwa. Once in Kilwa, heavy tariffs were levied on the bullion and on all other goods that passed through the port. The sultan's palace of Husuni Kubwa, containing more than 100 rooms, was said to be the largest building in Africa south of the Sahara. The indefatigable traveler ibn-Battuta, visiting the city of Kilwa in 1331, declared it to be "one of the most beautiful and well-constructed towns in the world."

The reasons why the Swahili culture and the influence of Islam did not penetrate farther inland were mainly geographic. Between the temperate grasslands and forests along the coast, watered by the monsoon rains, and the great lakes of the interior lay a wide belt of dry scrubland sparsely populated by tribes of warrior pastoralists who had neither the need nor the desire to alter their traditional patterns of life. Very few traders or foreigners ventured far from the coastal cities, although those who did were intrigued by what they found. A certain Chinese traveler, for example, gave a vivid account of two animals that were unfamiliar to him: One was "a kind of mule with brown, white, and black stripes around its body"; the other "resembles a camel in shape, an ox in size, and is of a yellow color. Its forelegs are five feet long, its hind legs only three feet. Its head is high up and turned upward." He was describing, of course, a zebra and a giraffe.

In the early decades of the fifteenth century, several expeditions from China arrived in the east-coast ports, whose prosperity continued unchecked. In 1415, a giraffe was sent from Malindi as a gift to the emperor of China, cementing this profitable partnership. But the exposed position of the trading cities and their lack of firm control over the hinterland were eventually to prove their undoing. They were discovered by the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama after he rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1497; in the following decade, almost all the ports were sacked by Portuguese troops, and with them was destroyed the network of trade across the Indian Ocean. The coral palaces of the merchant rulers lay empty and in ruins.

Both Mali and the city-states of the east coast profited during the fourteenth century from trade and other friendly contacts with powerful Islamic countries in North Africa or across the Indian Ocean. These factors, however, were not indispensable in order to achieve prosperity. In the majestic mountains and on the sweltering plains of northern East Africa, inland from the coast of the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa, there flourished a kingdom that could hardly have been more different from Mali: It had no important trading ports, it was almost completely cut off from the outside world, and its religion was Christianity.

Christian doctrines had gained a firm foothold in Africa during the first centuries AD, when much of North Africa was governed by the Romans. How the religion arrived in the country that was to become known to outsiders as Ethiopia—from the word used in Greek texts of the Bible to describe the black peoples of Africa—was recounted by a chronicler named Rufinus shortly after the event occurred. A ship carrying a Syrian monk and his two young students home from India landed on the west coast of the Red Sea and met a hostile reception. After the monk and all the ship's crew had been killed, the two students, Aedisius and Frumentius, "were found studying under a tree and preparing their lessons." These evidently model children were taken as gifts to the king of the country. Aedisius became the king's cupbearer while Frumentius, whom the king perceived to be "sagacious and prudent," served

Constructed out of coral stone in the early fourteenth century, a sultan's palace dominates a cliff top on the island of Kilwa, just off the east coast of Africa. This edifice was the largest domestic residence in all of equatorial Africa. With more than 100 rooms, an octagonal bathing pool, and separate sections for residential and commercial purposes (inset), the palace advertised the ruler's wealth and power, which were based upon Kilwa's monopoly of the trade in gold transported from the interior.

Kilwa was one of the foremost of a string of more than thirty trading centers that thrived during the fourteenth century along the east coast of Africa. The distinctive

Swahili culture of these mercantile centers emerged from a union of Bantu African and Muslim Arab influences. African goods arrived overland and in coastal vessels such as the one shown below; from Kilwa and the other ports, the merchandise was carried north to Arabia and east to India, Indonesia, and even as far as China.

As the royal secretary. After rising to high office, Frumentius was able to convert the king and his family to Christianity.

All this occurred around AD 350, and the kingdom in question was Aksum. The Aksumites wrote their language, Geez, in characters borrowed from the Sabeans of southern Arabia, with whom there had been strong trading and cultural links for many centuries. Out of this marriage of cultures came a rich and powerful state that survived into the ninth century, after which royal power moved south into the mountains of Ethiopia, at first to Lalibala and then, southward again, to the wild rifts and ranges of the kingdom of Shoa.

By this time, the other Christian states of Africa had succumbed to Islam. Christian Egypt had fallen to invading Arab armies in the seventh century, and in 1171, the Muslim lords of Egypt drove deeply southward into the Christian kingdoms of Nubia. But though sorely isolated from the rest of the Christian world by a ring of Muslim foes and rivals, the kingdom of Ethiopia became under the Solomonid dynasty a fortress of the faith that no aggression was able to overcome.

The dynasty was so named because its founder. King Yekuno-Amlak, who reigned from 1270 to 1285, claimed the dignity of descent from King Solomon of the Old Testament. How this came about was explained by the royal chronicler and also by wall paintings of the time, in graphic detail. The queen of Sheba (or Sabea) traveled to Jerusalem to visit Solomon, who admired her wealth and wisdom and her person even more. The chaste queen made Solomon promise not to take advantage of her and in return undertook not to take away any of his possessions. But after a great banquet including much wine and highly seasoned food, the queen woke in the night and drank water from a jar. Solomon, who had planned this event, accused her of taking what did not belong to her; the queen confessed her guilt and released Solomon from his promise. It was from their child, Menelik, that Yekuno-Amlak claimed direct descent.

The survival of Christian Ethiopia—or Abyssinia, as it was known to its own people—depended first of all on its ability to withstand attacks by neighboring Muslim powers. Abyssinia's army consisted mostly of foot soldiers armed with swords, iron-tipped lances, and short bows; horses were rare, and probably only the commanders possessed them. The lack of cavalry and armor notwithstanding, Ethiopian forces defeated four Muslim invasions in the first half of the fourteenth century. Their success was largely due to the leadership of King Amda Tseyon (Pillar of Zion), who rewarded his troops generously. "He took from his treasury," the chronicles recorded, "gold, silver, and garments of great beauty, which he distributed among his soldiers from the greatest to the least important; Because, in his reign, gold and silver abounded like stones, and fine garments were as numerous as the leaves on the trees or the grass in the fields."

Partly for military reasons and partly to gather tribute from local centers of population, the kings of Ethiopia moved from one temporary capital to another, living with their entourage in huge encampments that were abandoned when the surrounding pasture and wood for cooking fires had been exhausted. But in other ways, they ruled as traditional African kings, concealed from their subjects in palatial tents when not on the field of battle or holding court, and enveloped in pomp and mystery. Possible rivals for the throne were confined with their families on flat-topped hills to which precipitous cliffs gave only the most hazardous access; no one was allowed to climb up or down without the king's consent, a concession rarely granted.

Most of the peoples of the kingdom were small farmers and stock raisers. In many regions, the fertile soil yielded several crops a year; cotton and coffee were grown as well as wheat, barley, and a highly nutritious grain called teff, unique to Ethiopia. The farmers might possess their own land and cattle, but they had to pay taxes and tribute and perform obligatory labor service for the high-ranking warriors and clergy. Failure to carry out such duties and other serious offenses were punished by flogging, which was applied with merciless whips. But it could often happen—especially with offenders who had influence at court—that the whips struck the ground instead of the offender, the object being to instill fear in onlookers as well as the offender rather than to cause injury. Ethiopian society was based on small communities, and personal dignities were precious.

Culturally, the single most important factor in Ethiopia's national identity was the Church. Since the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Christian churches in Africa had been separated from the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches in Europe by doctrinal differences, and when they ceased to use Greek after the Arab invasions in the seventh century, they had been further isolated by language barriers. The African Christians had become known as Copts—from the Arabic word for Egypt—and in the Muslim countries their numbers had dwindled. But in Ethiopia their faith had remained steadfast against the incursions of Islam, and the power of the Church was closely linked to that of the monarchy.

Continuing the tradition of patronage exemplified in the thirteenth century by King Lalibala, who had supervised the construction of a series of massive churches hewn out of solid rock near the town to which he gave his name, the Solomonid kings founded new monasteries and endowed the Church with vast holdings of land. In return, the church leaders actively supported the kings' wars against the Muslims and worked to convert the pagan tribes living in territory overrun by the army. The Ethiopian monks, the more ascetic members of the Church, produced fine manuscripts of chronicles, liturgical texts, and the lives of saints; they also maintained contact with their Coptic brethren in Egypt. Their extreme devoutness was personified by a fanatical monk named Eustathius, who mortified his flesh to prove his spiritual humility: He wrapped himself in iron chains that had been left in the sun until they were red-hot, so that his body resembled "a fish grilled in the fire."

The saints and holy men of the Church were celebrated in national legends that told of miraculous events. One such tale concerned Saint Abiya Egzi, who lived in the early fourteenth century: When the saint became lost while wandering in the wilderness, springs welled up to slake his thirst, wild animals approached to advise him, and an elephant guided him to a remote sanctuary. Another concerned a group of pilgrims who set out on a long and perilous journey and rested one night in a cave. The mouth of the cave became the mouth of a monstrous but kindly serpent that closed its jaws on the pilgrims and carried them safely to their destination.

Guided by the forceful successors of King Amda Tseyon, who died in 1344, Ethiopia continued to thrive throughout the fourteenth century. In 1352, when the patriarch of the Coptic church in Alexandria was imprisoned by the Mamiuk sultanate of Egypt, King Saifa-Arad secured his release by threatening to execute or forcibly convert all Egyptian traders who ventured into Ethiopia; thereafter, relations between the two countries became increasingly friendly. Coptic texts in Arabic were translated into the Ethiopian liturgical language of Geez, and the church acquired from Jerusalem venerable holy relics including an alleged piece of the cross on which Christ

M

Was crucified. Tribute was exacted from some of the small independent Muslim states on the southern borders. And as Ethiopia's power and influence expanded, its isolation from the rest of the Christian world diminished.

Instrumental in the renewal of contacts with other Christian nations was the legend of Prester John. Since the time of the Crusades in the twelfth century, stories had circulated in Europe about a remote Christian ruler somewhere in the East. Believing this rumored sovereign to be a potential ally in their wars against Islam, European adventurers had sought for his kingdom in central Asia. But in 1306, a delegation of Ethiopians traveled to Europe and described to a Genoese cartographer, Giovanni da Carignano, their "most Christian emperor of Ethiopia," who owned the allegiance of seventy-four kings and of innumerable princes. From then on, the focus of the legend became Africa.

An increasing number of hardy European travelers, many of them motivated by the quest for Prester John, found their way into Ethiopia, where their skills were put to good use. One of them, a Venetian painter named Nicolo Brancaleone, resided in the kingdom for forty years in the fifteenth century, working on the decoration of churches; he was described by another visitor as "a very honorable person and a great gentleman, though a painter." In the early sixteenth century, Portuguese ships arrived in the Red Sea, and Ethiopia, beset by an invading Muslim army equipped with

Firearms and artillery, was saved from complete destruction only by the timely arrival of a force of Portuguese musketeers. By gradual stages, Ethiopia was thus drawn back into the worldwide Christian community, while maintaining the distinctive African traditions developed during its proud isolation.

For Europe and Asia in the fourteenth century, Africa south of the Sahara was represented by the gold, ivory, and slaves exported from Mali and the east-coast trading ports. Even the artifacts and monumental building works of the peoples of the interior remained largely unknown to the outside world: The rock churches of Ethiopia were first visited by Europeans toward the end of the fifteenth century, and the massive stone-built enclosure of Zimbabwe was not seen by Europeans until the latter part of the nineteenth century. Within this vast and unexplored continent, however, there existed peoples and cultures whose range and diversity made that portion of Africa known to the outside world seem like the tip of an iceberg. “The inhabitants of his country are numerous, a vast concourse,” wrote the Arab scholar al-Umari of Mansa

Musa's empire of Mali, "but compared to the peoples who are their neighbors and penetrate far to the south, they are like a white birthmark on a black cow.” Materially simple but culturally complex, the productive and organized lives of these people represented an achievement no less real than the opulent splendors of Mali or Ethiopia. They had mastered the problems of

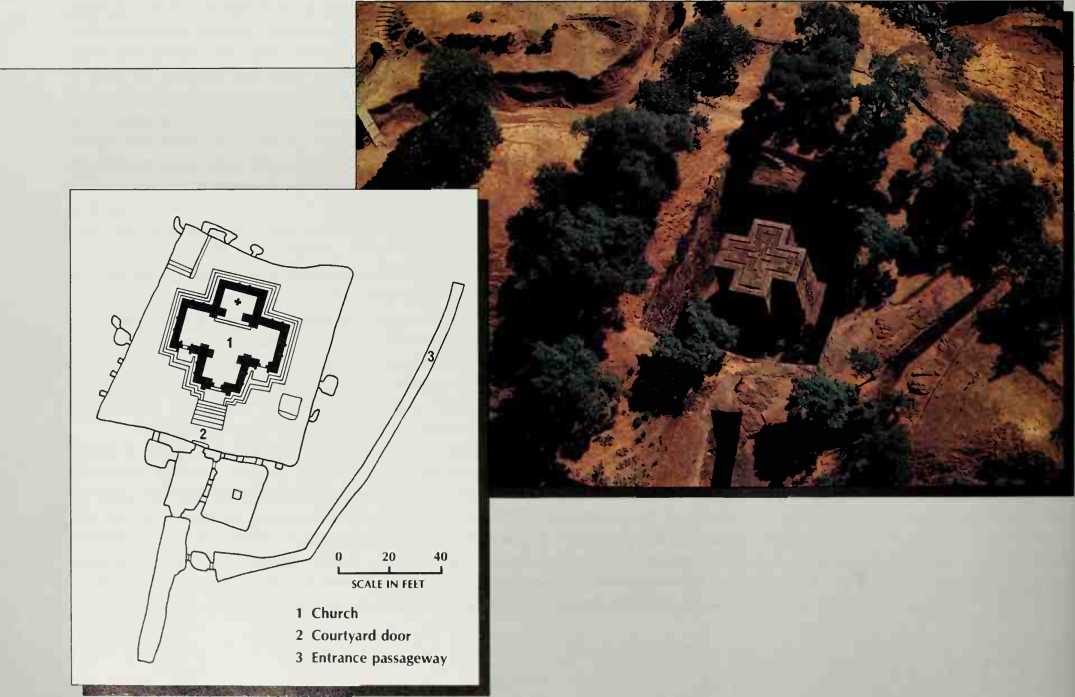

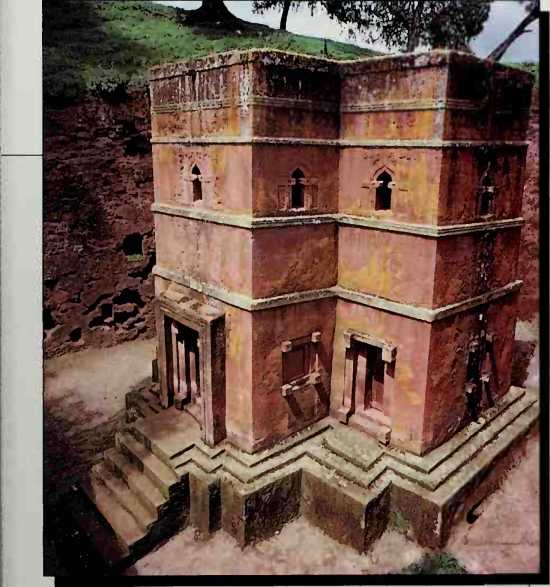

In Ihe rocky Ethiopian uplands of the Horn of Africa, the monolithic church of Saint George stands in an excavated pit forty feet deep. Tombs and monks' cells were cut into the side of the pit, and worshipers gained access to the church by following a sloping passage cut into the surrounding plain (plan, far left).

Carved from solid rock in the shape of a cross and then hollowed out, this church was one of a group of ten in the vicinity that were constructed during the thirteenth century on the orders of King Lalibala, one of the most passionately devout of Ethiopia's Christian rulers.

Cavelike churches had been hewn out of the faces of cliffs in many places before, but freestanding buildings were an Ethiopian innovation. These churches were probably built with the assistance of Egyptian Coptic Christians fleeing persecution at the hands of the Muslims.

World History

World History