The IRA, dominated more by its nationalist than by its socialist wing, issued an ultimatum to Britain to withdraw from Northern Ireland. The organization subsequently undertook a bombing campaign in several British cities, which brought scores of casualties. The Irish government responded to this presumption by an irregular group to act for the Irish people by resorting to the same machinery that the Irish Free State government had employed. Legisla-

Tion allowed the establishment of military tribunals, internment without trial, and a treason act with a death penalty was passed. When the European war began in September, Ireland, like the other smaller European nations, declared its neutrality unless attacked by either Germany or the Soviet Union. However, the Bail passed legislation proclaiming a national emergency, enabling the constitutionally stipulated wartime rules, which gave considerable arbitrary power to the state, to apply even though war had not been formally declared.

Ireland would persist in its neutrality throughout the Second World War despite enormous pressures, especially from Great Britain and the United States, to more openly identify with the Allied side. No doubt Irish popular opinion stood on the side of the Allies against the Axis, but de Valera had to contend with the reality of a significant IRA presence in Ireland that would regard any alliance with Britain, considered as "occupying" Northern Ireland, as a betrayal of the nationalist vision of a united Ireland. In addition, the war of independence had occurred less than a generation before and bitterness in many circles was still too close to the surface to be evoked, as would be the case were Ireland to formally join with Britain in the war effort.

On the other hand, the Irish were adamant in rejecting limited overtures by Germany to aid the Axis. Nazi Germany had sought to work with the IRA to foment disturbances behind the lines for the British in Ireland and Northern Ireland. Sean Russell, the leader of the IRA who had made his way to Germany from the United States, and his left-wing opponent, Frank Ryan, who had fallen into German hands after having been captured serving the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, were reconciled and placed in a U-boat that headed for Ireland in early 1940. However, the mission was aborted when Russell died. Ryan died a few years later in Germany. There were several other German efforts at parachuting agents into Ireland during the war, which were generally unsuccessful.

Overtures by Winston Churchill, especially upon the American entry into the war in December 1941, for the Irish to join the war effort with a suggested reward of reunification of the island were rejected by de Valera as were all appeals to readmit the British navy to the ports that they had relinquished in the 1938 agreement. The Irish government disapproved of the arrival of American troops in Northern Ireland in 1942 and the establishment of an American naval base in Derry, which inhibited the free movement of American military in Northern Ireland on personal visits to Ireland. However, Irish fire brigades and other relief services readily joined in providing assistance to the people of Belfast when that city became subject to severe German bombing in the spring of 1941. Dublin itself experienced limited and accidental German bombing about the same time. The following year the Irish government disallowed the use of a radio transmitter by the German embassy in Dublin lest it serve to provide intelligence and even weather information to Axis forces. Throughout the war, German airmen who survived crashes or who had to make forced landings in Ireland, usually after missions over Britain or in the Atlantic, were interned for the duration of the war, whereas British personnel in similar circumstances were returned home.

There was much talk that the unavailability of the Irish ports to the British and the Americans inhibited the struggle against the U-boats, which were wrecking havoc on trans-Atlantic shipping. On the other hand, facilities in Northern Ireland gave substantial assistance for conducting the North Atlantic campaign. Furthermore, Irish attachment to the Allied cause would have opened up the generally poorly protected ports and cities to German assault. It is generally conceded that Irish intelligence sources were very cooperative with the Allied effort throughout the war and the British embassy in Dublin was usually unsympathetic to exerting any pressure on the Irish. The American ambassador, David Gray, a cousin of the American first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, however, was quite undiplomatic in his criticism of the Irish. Probably his outspokenness reflected another agenda, namely, to weaken the political strength of Irish-American opponents of President Franklin Roosevelt, who aspired to secure an unprecedented fourth term. Whatever their effect on American politics, Gray's antics rebounded very much to de Valera's advantage, as Fianna Fail swept back into power with an absolute majority in the May

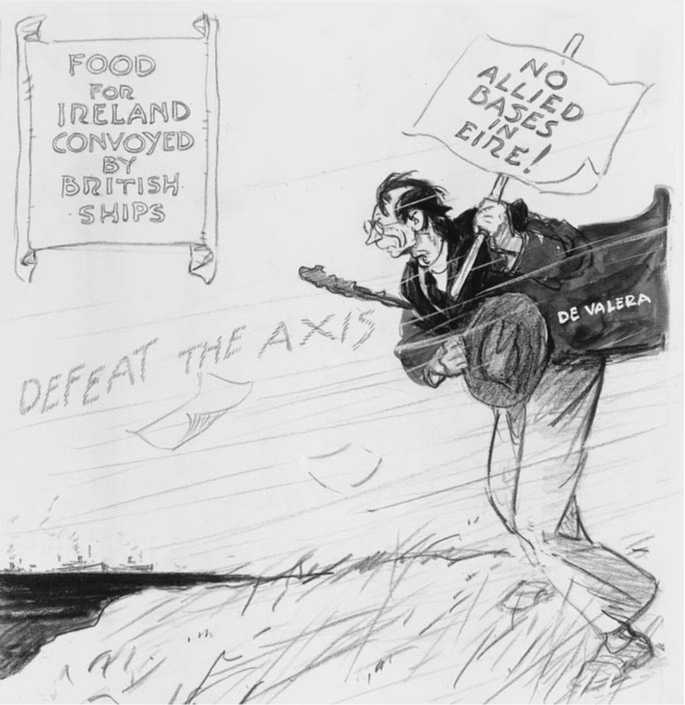

Cartoon shows Eamon de Valera holding a sign reading "No Allied Bases in Ireland,” as he struggles against a gale labeled "Defeat the Axis.” During World War II Ireland remained neutral, despite Allied pressure. (Library of Congress)

1944 general election, after having slipped to a mere plurality in an election the previous year.

Toward the end of the European war, de Valera made a gesture, difficult to understand, of calling on the German embassy in Dublin to extend his condolences upon the death of Adolph Hitler, a visit that probably confused even the Germans. Some have argued it was the mathematical and theological side of de Valera prevailing, as it was necessary to the very end to demonstrate the Irish position of neutrality. Others argue it was done to provoke the British so as to enable Fianna Fail to benefit from the inevitable anti-British backlash in forthcoming by-elections. Provoke it did, as Winston Churchill's victory speech thanked the people of Northern Ireland for their war efforts, which he contrasted with those who benefited by remaining neutral from the sufferings of others. De Valera's rejoinder was an effective, at least to an Irish audience, reminder to the wartime leader that, in his understandable sense of triumph, he had forgotten the legacy of a people who had suffered 800 years of tyranny.

The emergency had brought much discomfort to the Irish, especially shortages of many imports, as British shipping that would have brought such materials had been absorbed in the war effort. There was severe rationing, including restrictions on the use of automobiles, and censoring of the media. Newspapers were inhibited from giving any war news that might reflect sympathy for either side. On the other hand, those Irish who had radio receivers were able to regularly obtain BBC reports and thousands of Irish from both parts of the island were serving in the British forces. Possibly the information isolation of the Irish in the war years gave them a provincialism that would explain their naive expectations in the immediate postwar years that they would have a world audience for their complaint about the partitioning of the island of Ireland.

The shortages of the war years would also have the effect of shaking the populist mandate for Fianna Fail, especially among its natural constituency, the small farmers, who sensed the benefactors of the regime were increasingly manufacturers of protected, and often inadequate, domestic goods. An example of dissatisfaction was the emergence of a new farmers' party, Clann na Talmhan, whose strength in Dail fiireann rose to 11 when Fianna Fail regained its absolute majority in 1944. On the other hand, the major opposition party, Fine Gael, continued in its downspin, as its numbers in Dail fiireann in the successive elections of 1937, 1938, 1943, and 1944 went from 48 to 45 to 32 to 30. Not surprisingly, its leader, William T. Cosgrave, resigned and was replaced by another stalwart of the Irish Free State, the former minister for defense, Richard Mulcahy, in 1944. Also, the Labour Party experience a split, as a breakaway group, led by William O'Brien of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union, who objected to the return of James Larkin and his more radical ideology to the party and formed a rival National Labour Party. But a potentially troubling development to Fianna Fail domination was the formation, in 1946, of a radical republican party called Clann na Poblachta and headed by IRA veteran Sean MacBride, which could present itself as doing what Fianna Fail had done 20 years earlier: moving beyond the purely nationalist theme and rallying the disinherited and dissatisfied. Its victory in a number of by-elections in late 1947 gave the movement great expectations for the next general election.

World History

World History