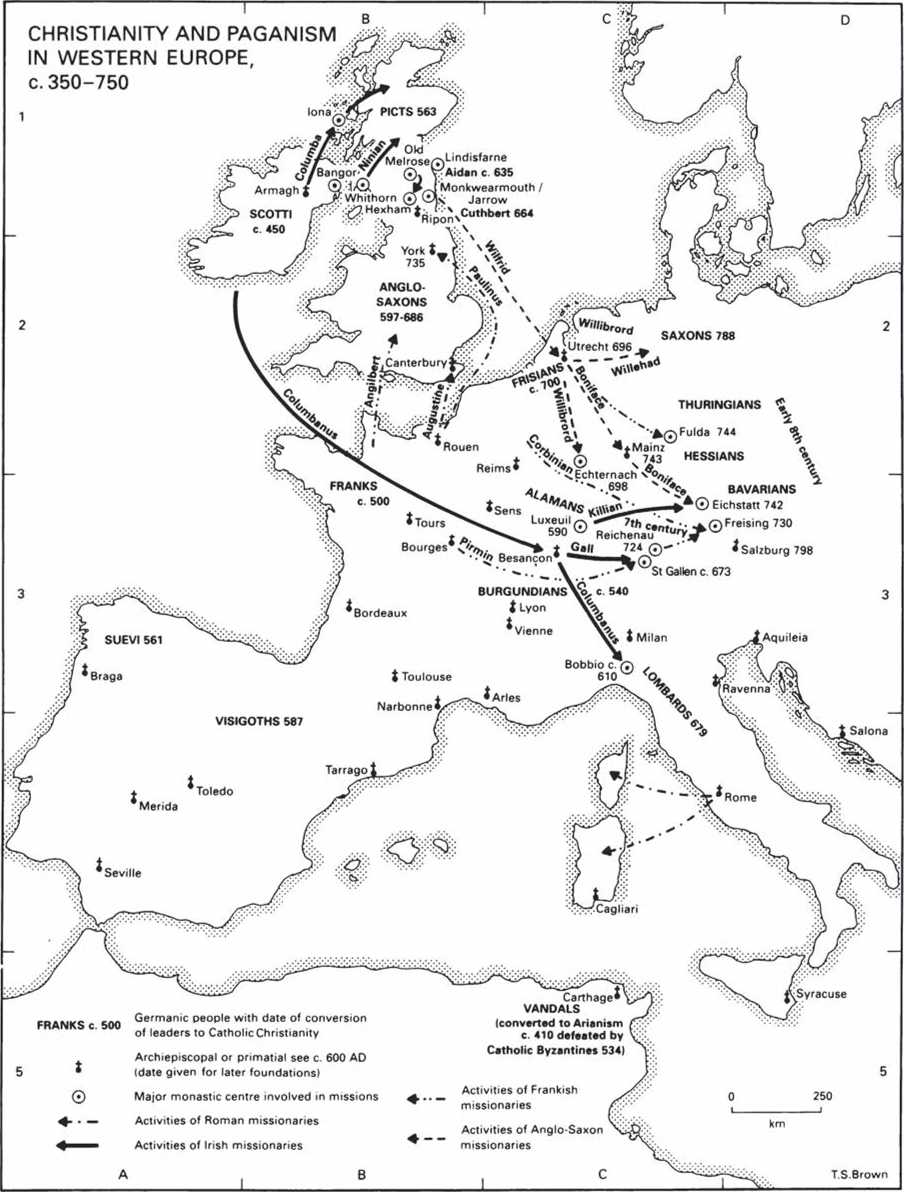

Christianity and Paganism in the West, c. 350-750

Before and after the conversion of the Emperor Constantine (312-37) Christianity was less established in the West than the East. The problem of the strength of paganism was compounded by the less urban character of the West, lack of local pastoral institutions and of clear hierarchical organization, theological divisions in the church, and the increasing pressure from barbarian settlers, most of whom were either pagan or Arian (following the conversion of the Goths by Ulfila). The close alliance between Church and state in the East was not replicated in the West and the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 led to a bitter debate between Christian and pagan apologists. Nevertheless, Christianity did much to strengthen its hold on the West from the late fourth century. The western emperor Theodosius I (379-95) took a firm line against Arianism and paganism, a formidable series of Latin theologians such as Ambrose (d. 397) and Augustine (d. 430) strengthened the Church's doctrinal position, and the conservative senatorial aristocracy finally abandoned paganism in the early fifth century. By the pontificate of Leo the Great (440-61) the see of Rome had built up a complex bureaucratic structure, emerged as the spokesman of the West in disputes with the East and on the basis of its petrine origins claimed special authority in the West including final ecclesiastical jurisdiction and the right to confirm appointments. The weakening of imperial institutions led to an enhanced political role for the bishops in Rome and other cities. Bishops took over social and charitable services in their cities, negotiated as the representatives of the Roman communities with barbarian leaders and reinforced their hold over their flocks by skilful manipulation of ceremonies and the cult of saints. The migration from the East of monastic leaders such as Athanasius and John Cassian helped spread the phenomenon of monasticism. Although it differed in being more aristocratic and urban, individual monastic figures such as St Martin of Tours (d. 397) and St Severinus of Noricum (d. c. 470) played an important role in the leadership of their local communities and in evangelizing the countryside.

The collapse of the empire led to a general extension of the Church's power, but its position in particular areas in the sixth century varied according to political circumstances. Southern Britain was one of the few areas where an almost complete disruption of ecclesiastical structures is evident. In Africa, Spain and Italy the predominantly Arian regimes of the Vandals, Visigoths, Ostrogoths and Lombards restricted the Church's influence, although outright persecution was rare. In the Celtic north-west conversion of southern Scotland and of Ireland had been undertaken in the fifth century by the missionary bishops Ninian and Patrick, but in the sixth century the kin-based, non-urban nature of society promoted the emergence of an increasingly monastic form of church. On the continent new sees were founded, councils regularly convoked, and supervisory powers accorded to the heads of provinces (metropolitans or archbishops). With the spread of monastic rules such as that of St Benedict (d. 547) increasingly missionary work became the preserve of more disciplined and committed monks. Examples include the Irishman Columba, who initiated the conversion of the Picts from Iona c. 565, St Augustine, sent by the powerful Pope Gregory the Great to evangelize the English in 597 and Columbanus (d. 615) whose austere

Irish foundations in Gaul and Italy extended the appeal of Christianity among Germanic aristocrats. The extension and organization of the English Church was largely the work of monks, either Irish-inspired, such as Aidan at Lindisfarne, or Roman in allegiance such as Wilfrid at York. By the late seventh century Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries were winning converts and setting up sees east of the Rhine, the most prominent leaders being Willibrord and Boniface.

By 750 little headway had been made in converting pagans outside the old Roman Empire. Nominal Christians remained attached to traditional Germanic values and superstition remained widespread in the countryside, partly because local parish structures did not yet exist. However, by vastly improving its hierarchical organization, its writings and the quality of its trained personnel the Church had done much to spread its ideals.

T. S.Brown

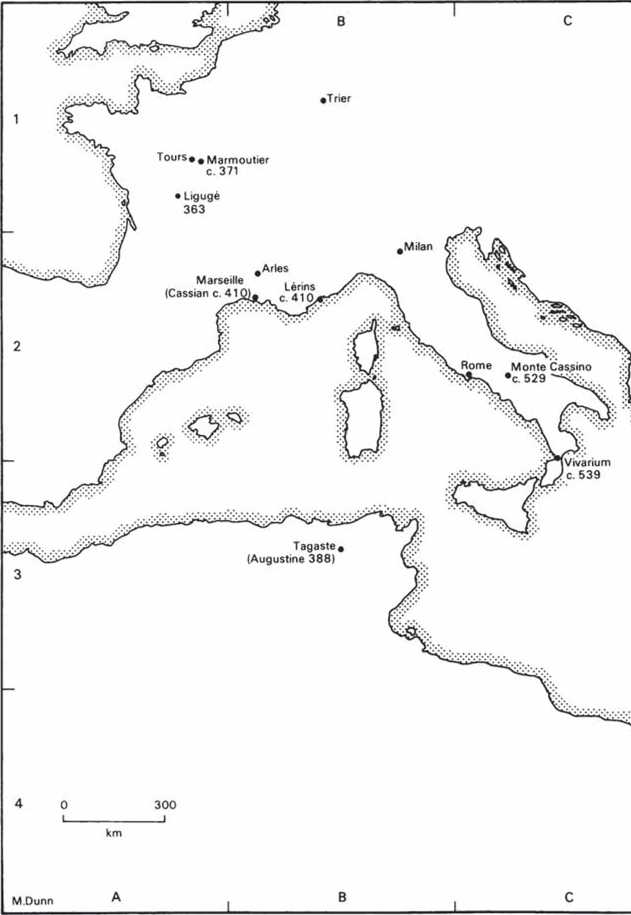

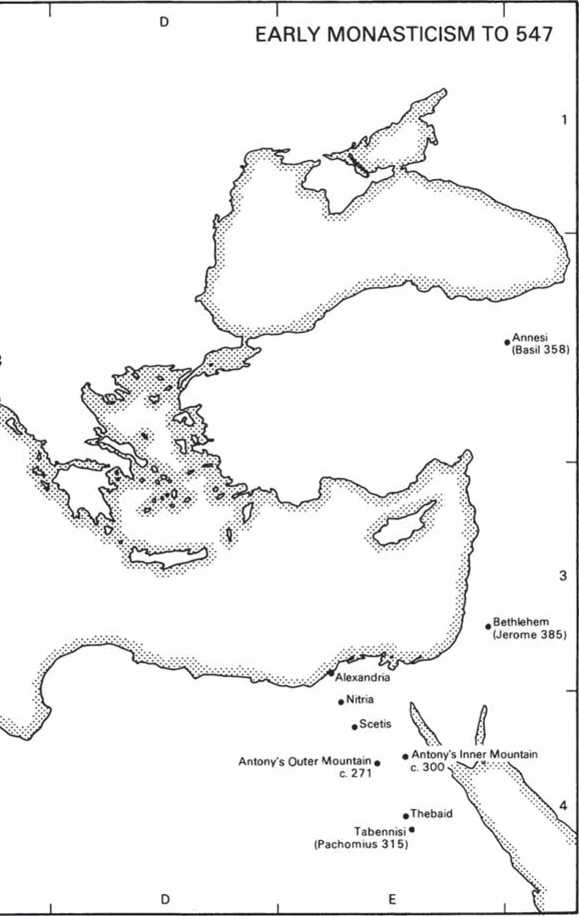

Early Monasticism to 547

The recorded history of Christian monasticism begins in the Middle East in the late third or fourth century. Although not the first Christian solitary, the Copt Antony (?251-?356) is regarded as the father of Christian eremiticism (eremos = desert in Greek), spending many years in prayer and contemplation on the edge of the Egyptian desert and latterly retreating to his 'Inner Mountain'. By the mid-fourth century at Nitria, near the mouth of the Nile, at Scetis to the south and in the Thebaid in Upper Egypt colonies of several hundred hermits could be found: such a grouping was known as a lavra (from the Greek for a lane or passage). Its inhabitants lived in separate cells, but there were common buildings including a church where all gathered on Saturdays and Sundays for communal prayer and mass. The lavra spread to Syria and Palestine as did the cenobium (from the Greek koinos &ios=common life), also Egyptian in origin, and founded by another Copt, Pachomius (c. 292346). The first Pachomian community was at Tabennisi on the Upper Nile: such communities were very large, and the monks (or nuns) lived together in a number of houses and supported themselves by handicrafts. Cenobitism was spread to the eastern empire and was further refined by the intellectual and theologian Basil of Caesarea (329-79), who entered the monastic life at Annesi and who eventually achieved a more integrated community than that of

Pachomius. He stressed the need for the monk to exercise Christian charity towards his fellows. It is generally held that the monastic movement in the western empire began its real evolution under the influence of the East although there already existed an independent tradition of Christian virginity and asceticism and it is possible that the description of the Antonian or lavrastyle monasticism established at Liguge and Marmoutier by the 'father' of Gallic monasticism, Martin of Tours (d. 397), stemmed from his hagiographer's knowledge of the East as much as Martin's own practice. The visits of the exiled Archbishop Athanasius of Alexandria to Trier and to Rome (335-7 and 339-46) may have inspired western monasticism, but possibly even more influential was the translation in the fourth century into Latin of his Life of Antony which would become a classic of hagiography and a model for the ascetic life and was the first of several works about the 'desert fathers' to reach the West. Augustine's conversion to a Christian life followed his introduction at Milan to the Life; he founded his own monastery at Tagaste in his native North Africa in 388 and wrote an eastern-influenced Rule for his sister's community of nuns. Eastern ascetic ideals were imported into the West by Jerome, who founded his own monastery in Bethlehem in 385 and by Honoratus who founded Lerins c. 410 on his return from travels in the East. About the same time, John

Cassian, who had spent a considerable time in eastern monastic communities, and who compiled the Conferences of the desert fathers, founded two cenobitic houses at Marseille. His Institutes represent the earliest surviving work of monastic instruction composed in western Europe which gave detailed descriptions of the practice of the East. In the sixth century, southern France and Italy produced a number of cenobitic Rules including those by bishops Caesarius (c. 470-542) and Aurelian (d. 552) of Arles and the (perhaps surviving) compilation of Eugippius of

Lucullanum. More controversial is the Rule of the Master which is said to have influenced Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Monte Cassino (c. 480-c. 547). Benedict's Rule was not, in any case, an isolated work but reflects both contemporary practice and earlier teaching. It divided the day of the monk between worship (eight offices), reading (lectio divina) and work. At Vivarium, founded by Cassiodorus, monastic life was combined with a well-organized programme of studies.

M. Dunn

World History

World History