We want to find sites where both documentary and physical evidence exist which can be used to argue that there were other, new and different structures in twelfthcentury Ireland which could relate to later castles. The documentary evidence has been assembled by O’Corrain (1974) and consists of brief entries in Annals. Most are from the Annals of Tigernach and relate to sites of the O’Connor kings of Connacht from 1124 onwards. They use a word new to Irish to describe a number of sites as ‘caistel’, or ‘caislen’, loan-words from Latin castellum or medieval French chaste!. The same Annals use the word to describe the castles of the English after 1169. Another reference, in the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters for 1166, states that the enemies of Diarmait Mac Murchada burned his stone house at Ferns (Fig. 1) and the ‘longport’ there. It should be noticed, however, that the entry reads as though his house was not actually in the longport or fortress. A fort separated from the residence of the king is not the sort of thing that we are looking for in a castle. With the places named in the Annals, we do not know whether it is right to accept that a new word must mean a new thing. The period was one of dynamic political change which could either have seen new kinds of sites deployed, or it could simply have seen men attracted to new, fashionable or boastful words: English people had eaten pigs before they started to call their meat pork.

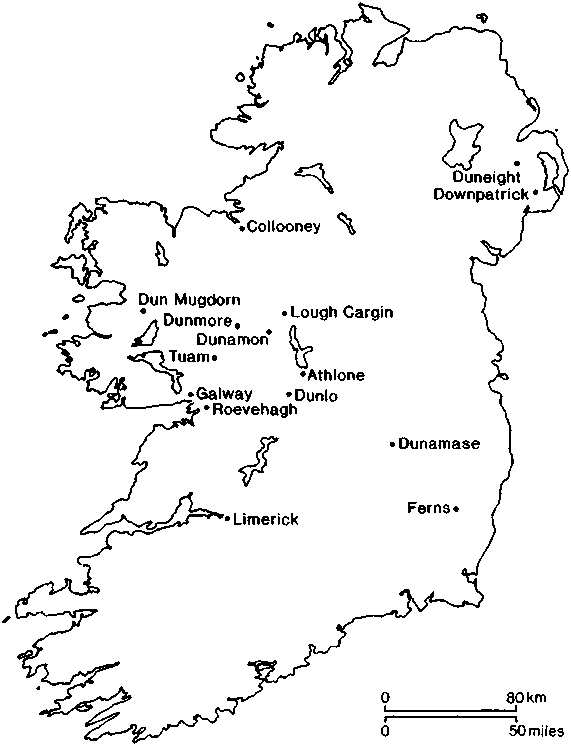

Figure 1 Map of possible castle sites in Ireland from before 1166

There has been an attempt to link these Connacht references to physical evidence of a new type of site, so that we could talk of castles from the century before 1166 (Graham, 1988). Unfortunately, the only one of the list which Graham specifically identifies as a new type physically is Dunmore, which he identifies as a motte, i. e. as an artificial mound of earth (ibid., 115). In fact, the site is one whose present remains are those of a later thirteenth-century masonry castle set on a natural rock outcrop: in no sense can it now be identified as a motte. Other sites which he claims as early castles cannot be distinguished from the traditional corpus of raths or ringforts, and so the connection between the new word and a new type of site is not made, nor does he establish any way of

Recognising such new sites, other than by references in documents. The argument is not advanced beyond that of O’Corrain.

In fact two sites do exist which combine physical and documentary evidence of being something new. The site of Duneight, Co. Down, should be the starting point for discussion of the physical evidence, for it has both been excavated and identified as a place mentioned twice in the Annals of Ulster (1983, s. a. 1003/4 and 1010/1). On the second occasion, Flaithbertach ua Neill of the Cenel Eoghain is recorded as burning the fort and destroying the township of Duneight, before extracting the submission of the king of Ulaidh. Royal associations may have led to its inclusion in the dower charter of John de Courcy, the first English lord of Ulster and in a sense continuator of Ulaid kingship (Otway-Ruthven, 1949, 78-9: Dunechti should be identified with Duneight rather than Donaghy, Co. Antrim).

The excavator (Waterman, 1963) considered that the large inner ditch and the reinforced bank which went with it were both of the tenth or eleventh century and rightly stressed their difference from the normal rath enclosure. It is possible, and the excavation was not by any means perfect, that this ditch cut through an earlier, much shallower one, and the strongly military defences might be later than this date, indeed date to the time of de Courcy. It would still leave the fact of the large size of the enclosure, and its associations with both royalty and a township, distinguishing it from traditional raths.

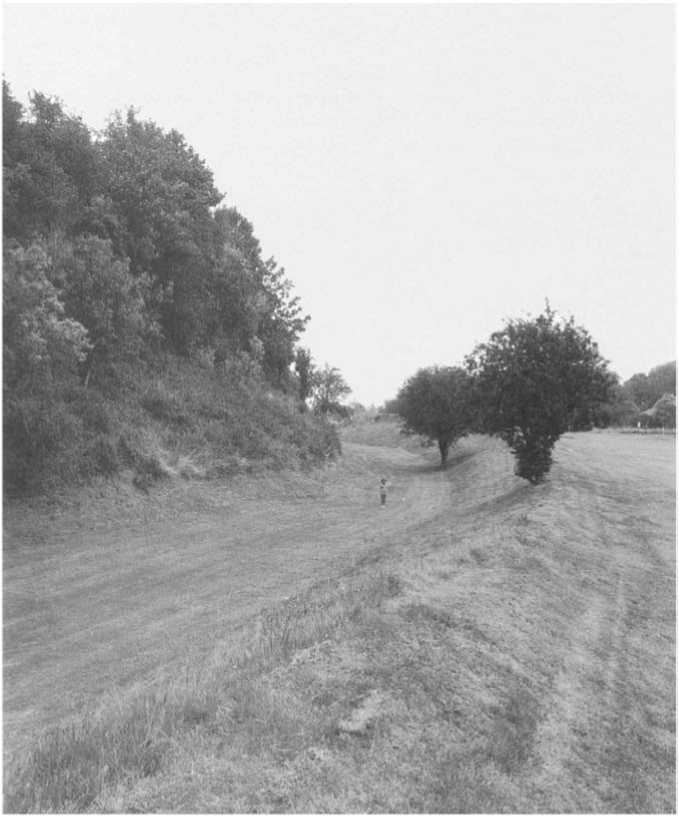

The best physical evidence, although unexcavated, comes from the so-called ‘English Mount’, a large enclosure set at the edge of the Quoile marshes northeast of the hill on which Downpatrick cathedral is sited (Jope, 1966, 202-3). The enclosure is enclosed by particularly massive defences (a ditch and a bank rising 6 m (20 ft) higher than the interior, and up to 15 m (50 ft) above the ditch fill) on the line of approach from the ridge leading up to the cathedral hill (Fig. 2), while the marshes reinforce the defences of the other sides. Inside is a motte which looks unfinished, with a smaller ditch on the north side where the mound perimeter is incomplete. The motte is sited awkwardly against the enclosure bank, and the bank at that point is higher than the motte; it is unlikely that builders of a motte and bailey castle would proceed to build the bailey first and then start in on the motte. The whole makes no sense as a motte and bailey, but it is likely to be an enclosure with an unfinished motte added later.

There is no direct evidence of the date of the enclosure, but it is very tempting to identify it with the royal, secular site of the eleventh and twelfth centuries situated at Downpatrick (Flanagan, 1973). The documentation of Downpatrick in the earlier twelfth century is also interesting for it associates the royal site with the site of a cathedral, the hallmark of the contemporary Church reform. Two centres of the new power were apparently set side by side here, and it is surely significant that this was the site of a town soon after the seizure of the kingdom by de Courcy in 1177. The centralisation of wealth would attract merchants in the classic configuration of eleventh century power.

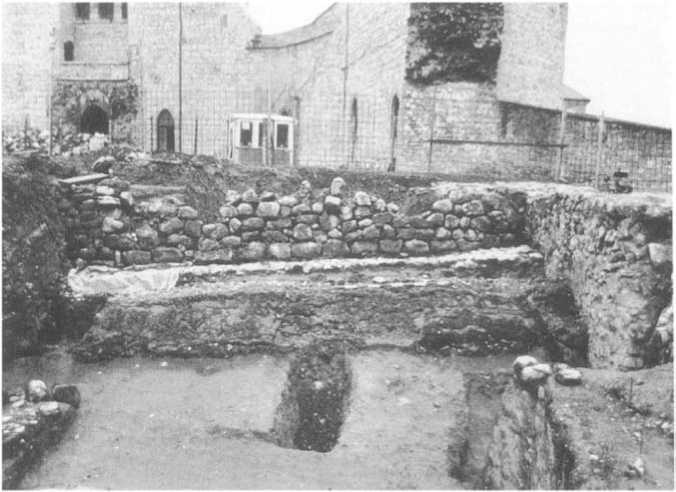

Recent excavations have added two other sites to the list. Excavations at Limerick castle in 1990 exposed the remains of an enclosure earlier than the extant remains of the stone castle (Wiggins, 1991, 43-4). It was strongly defended by a ditch up to 2.8 m (9 ft) deep and over 11 m (36 ft) wide in front of a bank revetted by a dry-stone wall (Fig. 3). The remains look too strong to be a temporary camp occupied before the construction of the castle shortly after 1210 (see chapter 2), but yet with their use of dry-stone revetment do not look like an early English castle, where one would expect timber. It is very tempting to identify it with a twelfthcentury Ua Briain fortification within the city.

The later castle of Dunamase dominates the Midland plain of Laois from the hills to its south. Excavations in 1994 and 1995 have greatly extended our knowledge of the site. Along the line of the present main curtain wall, Hodkinson found two earlier periods (Hodkinson, 1995). The first was a dry-stone wall cut into the rising hill-slope: the second was a mortared stone gate house inserted into this dry-stone wall. We cannot be absolutely precise about the dating of either of these, or indeed about that of the main curtain wall and gate house, but it seems likely that the dry-stone walling pre-dates the arrival of English lords in the area, but not by much. Its construction is similar to that of the dry-stone facing of the Limerick ditch, and it is certainly a site of much greater size and strength than any ‘normal’ Irish fort of the eleventh or twelfth centuries.

The sites named by O’Corrain from the Annals and those identified on the ground as belonging to the earlier twelfth century (Fig. 1) share some characteristics. They are mostly associated with the provincial kings, the major players in the politics of the period, not with the lesser kings who were slipping into a merger with the aristocracy. A high proportion of them have evidence of being reused as the sites of later castles. Limerick was a royal castle; Dunamase the caput of a section of the lordship of Leinster; Duneight retained by John de Courcy and the site of a motte. Downpatrick is not known as having had a castle of the Earl of Ulster (McNeill, 1980, 13) but the unfinished motte may mark an abandoned attempt to build one there, and the town of Downpatrick was certainly a key place in the Earldom. Of the documented sites, Ferns had been an important place since the twelfth century, while of the ten Connacht sites five were the sites of important castles. The new sites clearly were at places which the English of the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, as well as later generations, were to reuse as important. Those sites which can be identified on the ground are very much more powerful militarily than the traditional enclosures of earlier years, and cover a considerably greater area. Whether we should equate this with a greater military strength of the kings concerned, or see it as proof of the fear of attack, there is no doubt that they show an increase in the resources needed to build them over those of their predecessors.

We must sound two serious notes of caution. There are not many swallows here to make a summer. We cannot point to enough sites to argue that castles were regularly used in Ireland before 1166, or that their use requires us to think that the basis of Irish lordship had changed because of them. The power of kings

Figure 2 ‘English Mount’, Downpatrick: view along the defences on the land side

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Ireland rested overtly on naked military power, and these sites seem to reflect this. Nor can we point to a widespread use of the new sites, if such they are; those that we know of are associated with the major kings, not with the wider circles of lesser kings and aristocracy. If these sites mark a new departure for secular society, it is like the contemporary reform of the Church; led from the top and starting with the upper grades first, bishops before parishes. In both cases it is legitimate to question how far the new ideas were accepted beyond the power of the major kings. In this context, we might envisage that the lesser lords were those who continued to occupy the reduced

Figure 3 Limerick: the defences of the pre-castle enclosure, with the castle gate house in the background

Number of traditional sites, emphasising their importance with a new stress on mounds and height, but largely formally rather than with a real appreciation of their military potential. It is clear, however, that Giraldus Cambrensis’ sweeping statement that the Irish did not care for castles, but instead relied on the natural refuges of woods and bogs (Dimock, 1867, 182), was wrong; some clearly had fortifications.

In many ways the academic position about castles in Ireland before the English lordships were established is a mirror image of the parallel question of whether there were castles before 1066 in England. There the idea that castles were simply a Norman introduction was challenged in the 1960s. The argument that they existed in England before 1066 rested on two legs: that landed lordship of an essentially ‘feudal’ nature existed in Anglo-Saxon England, and that the lords had built defensive enclosures around their manor houses, which would be recognised in France, or elsewhere, as castles (Higham and Barker, 1992, ch. 1). Of the two legs, the first has stood the test of discussion better than the second. Studies of the pattern of land holding in the English countryside before 1066 show the existence of tightly organised estates, very similar to the later manors, and unlike the earlier extensive but loosely controlled lordship. On the other hand, the documentary references in pre-1066 chronicles are as ambiguous as those in Irish Annals. The sites which are proposed as castles, such as Goltho (Beresford, 1987) or Sulgrave (Davison, 1977), look, to an Irish eye, no more defensive than a rath, with low banks and shallow ditches, and without evidence of gate structures. In Ireland, by contrast, we have evidence of fortification, linked to royal power, but not of the structure of landed lordship parcelling out the landscape.

Here lies the nub of our view of what happened when Diarmait Mac Murchada invited English lords and troops from south Wales, most notably Richard fitz Gilbert (or Strongbow as he was later known), to Leinster after 1166. His immediate need was military force; he had been expelled from his kingdom by the High King and he wanted it back. But he went further and offered Richard his daughter in marriage and the succession to his kingdom (for a full discussion of these political events, see Flanagan, 1989). This may have been simply an added bait, to attract a man who was socially well above any mere mercenary soldier to be recruited for pay or loot alone, but it may be more. The kings of twelfth-century Ireland were well aware of developments outside Ireland. On the one hand they could see the military effectiveness of the feudal lords in England or Wales, but they had also the example of Scotland. There the kings had been steadily granting land to English lords, so that their kingdom would be transformed. The new feudal lords of Scotland introduced the methods of systematically exploiting estates and land for a greatly increased profit, compared to the traditional means of lordship. They did so in a context of a strict hierarchy of institutions, headed by the king, whose power was thus increased, but, above all, who gained greatly in authority. If such ideas were in Diarmait’s mind, we shall never know, and he died in 1171 before he had a chance to make it happen. Ireland lay open to the new lords and their system of organisation of the land.

World History

World History