The effects of the warfare of the seventh century - first the Persian invasions, then the devastation of the Arab invasions and raids - proved too much for the majority of provincial cities and their localised economies. The great majority shrank to a fortified and defensible core which could support only a very small population, housing the local rural populace and, where present, a military garrison and an ecclesiastical administration. Byzantine towns became merely walled settlements. Civic buildings were for the most part non-existent; the state and the church built, for their own use (churches, granaries, walls, arms-depots), but the cities had no resources of their own, no lands, no revenue, no corporate civic juridical personality.

Wealthy local landowners invested in building, but there is very little evidence until the eleventh century. Most invested whatever social and cultural capital they had in Constantinople and in the imperial system which became after the loss of the eastern provinces focused almost exclusively on the capital, for this ‘Constantinople factor’ was important for the contours of middle Byzantine society.

The cumulative result of these changes was that the ‘city’ effectively disappeared, and in its place there evolved the middle Byzantine kastron or fortress-town. The government and its military establishment contributed to these changes since they had the needs of local administration and the army firmly in the foreground. Distinguished by its limited extent and strongly defensive character, the kastron becomes the middle Byzantine urban settlement par excellence. In many contemporary sources the traditional Greek word for city, polis, is replaced by the new term, even when, in the later tenth and eleventh centuries, urban life began to flourish once more.

The archaeological and literary evidence bears eloquent testimony to the changes. The major city of Ankyra shrank to a small citadel during the 650s and 660s, the fortress occupying an area of a few hundred metres only. Amastris (mod. Amasra) offers similar evidence, as does Kotyaion (mod. Kutahya); many more formerly major centres underwent a similar transformation. The city of Amorion, defended successfully in 716 by 800 men against an attacking army more than ten times larger, was reduced in effect to the area of the citadel, or kastron, with an area of a few hundred metres. Excavations there and at several other sites show that while the very small fortress-citadel continued to be defended and occupied, discreet areas within the late Roman walls, often centred around a church, also continued to be inhabited. In Amorion there were at least two and probably three such areas. Sardis similarly shrank to a small fortified acropolis during the seventh century, but it appears that several separate areas within the circumference of the original late ancient walls remained occupied. At Ephesos, which served as a refuge for the local rural population, as a fortress and military administrative centre, but also retained its role as a market town, survey and excavation suggest that it was divided into three small, distinct and separate occupied areas, including the citadel. Miletos was reduced to a quarter of its original area, and divided into two defended complexes. Didyma, close by Miletos, was reduced to a small defended structure based around a converted pagan temple and an associated but unfortified settlement nearby. Other evidence for Euchaita, on the central plateau, may also support this pattern of development - a permanently-occupied settlement or settlements, perhaps concentrated around key features such as a church within the original late Roman circuit, with the citadel or fortress as the site of military and administrative personnel and the centre of resistance to attack. Archaeological survey and excavation show that the same holds also for the formerly thriving city of Sagalassos in Pisidia, and is probably true of many similar medium-sized towns.

The occupied medieval areas of most cities appear to have been similar in nature. It seems thus often to have been the case that separate areas within the late Roman walls of many cities continued to be inhabited, functioning effectively as distinct communities whose inhabitants regarded themselves (in terms of their domicile quite legitimately) as ‘citizens’ of the city within whose walls their settlement was located, and that the kastron, which retained the name of the ancient polis, provided a refuge in case of attack (although not necessarily permanently occupied or garrisoned).

As well as these ‘urban’ centres, there was also a large number of small forts, outposts and refuges, sometimes associated with nearby villages or towns, and generally sited on rocky outcrops and prominences (and often the sites of pre-Roman fortresses). Together with the provincial kastra, these characterised the provinces well into the eleventh century and beyond. And many larger or more important sites in Byzantine Asia Minor also fit the pattern. Apart from some already mentioned, such as Amaseia and Amastris, the fortresses at (Pontic) Koloneia, Herakleia Pontike/Kybistra, Charsianon, Ikonion, Akroinon,

Dazimon, Sebasteia in the central and eastern regions, Priene, Herakleia in Caria, and several others along the western coastal provinces, provide good examples, defended by natural features, adequately supplied with water, positioned to control the region around it together with the main routes, or means of access and egress serving the district, but often with a lower town located within the late Roman walls which remained occupied during times of relative peace. As long as the defences of the lower town were kept in reasonable repair, they might also serve as an appropriate refuge for the surrounding rural population during hostile raids, since small raiding parties rarely had the time or the strength to concern themselves with a siege, logistically demanding, very time-consuming and potentially very costly in manpower. This is a pattern typical also of Byzantine southern Italy and, with a different topographical context but a similar structural relationship to the surrounding territory, the Balkans.

1 Chalkedon

2 Nikomedeia

3 Nikaia

4 Malagina

5 Dorylaion

6 Kotyaion

7 Kaborkion

8 Amorion

9 Akroinon

10 Khonai

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Ephesos

Smyrna

Adramyttion

Attaleia

Seleukeia

Tarsos

Anazarbos

Germanikeia

Sision

Podandos

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Ikonion

Koron

Kaisareia

Charsianon

Ankyra

Amastris

Sinope

Amisos

Amaseia

Dazimon

31 Sebasteia

32 Trebizond

33 Koloneia

34 Kamacha

35 Melitene

36 Klaudioupolis

37 Euchaita

38 Gangra

39 Sozopolis

40 Rhodes

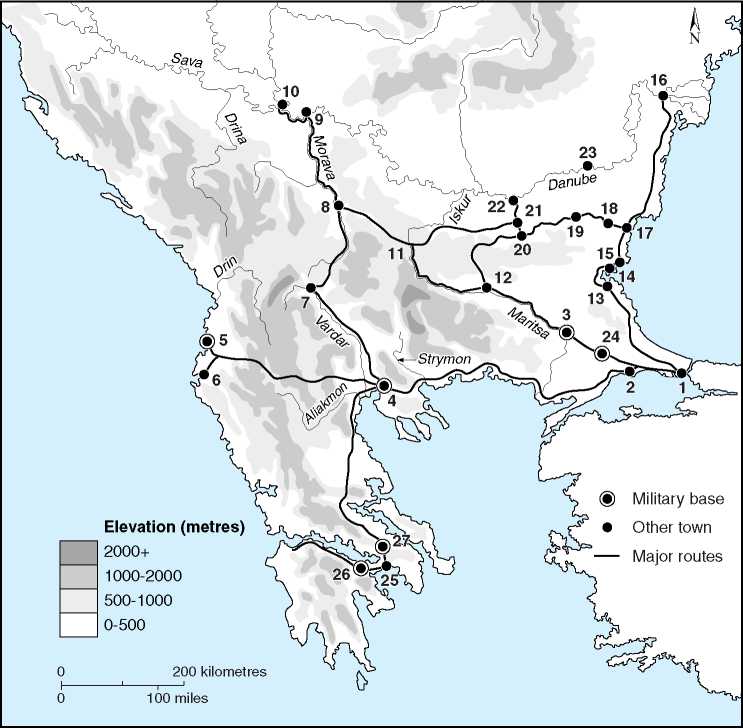

Map 6.8 Major fortified centres c. 700-1000.

|

1 |

Constantinople |

10 |

Singidunum (Belgrade) |

19 |

Pliska |

|

2 |

Herakleia |

11 |

Serdike (Sofia) |

20 |

Trnovo |

|

3 |

Adrianople |

12 |

Philippoupolis |

21 |

Nikopolis |

|

4 |

Thessalonica |

13 |

Develtos |

22 |

Novae |

|

5 |

Dyrrhachion |

14 |

Anchialos |

23 |

Dorostolon |

|

6 |

Avlona |

15 |

Mesembria |

24 |

Arkadiopolis |

|

7 |

Skopje |

16 |

Noviodunum |

25 |

Athens |

|

8 |

Naissos (Nis) |

17 |

Varna |

26 |

Corinth |

|

9 |

Viminacium |

18 |

Markianopolis |

27 |

Thebes |

Map 6.9 The Balkans: military bases.

These developments also impacted upon the demography and settlement pattern of the empire. Survey evidence suggests that villages around many cities attracted some of the urban population, becoming larger, sometimes defended or re-sited to defensible locations, and more nucleated. From the fifth century onwards there is evidence of a downward demographic trend, which is paralleled but somewhat preceded by the beginnings of a colder climate, and which lasts into the later eighth century. The arrival of plague (bubonic and pneumonic, although there is still some disagreement) in the eastern empire in the 540s had a significant negative impact on the population as a whole. Its reoccurrence thereafter into the middle of the eighth century, while it affected different regions in different degrees, nevertheless continued to affect population adversely.

Colder winters, lower agricultural outputs, a reduction in the amount of land farmed and the encroachment on marginal areas of habitation and cultivation of forest and woodland, all played a role. Byzantium was not alone, of course, since these changes affected the whole Eurasian zone. But the political and economic effects of warfare and conflict exacerbated the consequences for established patterns of settlement and land-use in the Byzantine context. The changing appearance and function of towns is a part of this broader picture. From the ninth century, in contrast, an amelioration of climatic conditions seems to have contributed to the revived fortunes of urban settlement as well as the demographic and economic improvement of the empire’s position, culminating in the twelfth century.

— Early Byzantine acropolis (7th-9th century)

“ Possible boundary of late Roman and early Byzantine city

— Middle and late Byzantine fortification walls (12th-early 14th century) H Late Byzantine settlement (13th-early 14th century)

A

N

Map 6.10 Development of the city of Pergamon in the late Roman and Byzantine period.

Map 6.II capital’.)

Late Roman and Byzantine Amorion in the 6th-9th centuries. (After Lightfoot, ‘The public and domestic architecture of a thematic

World History

World History