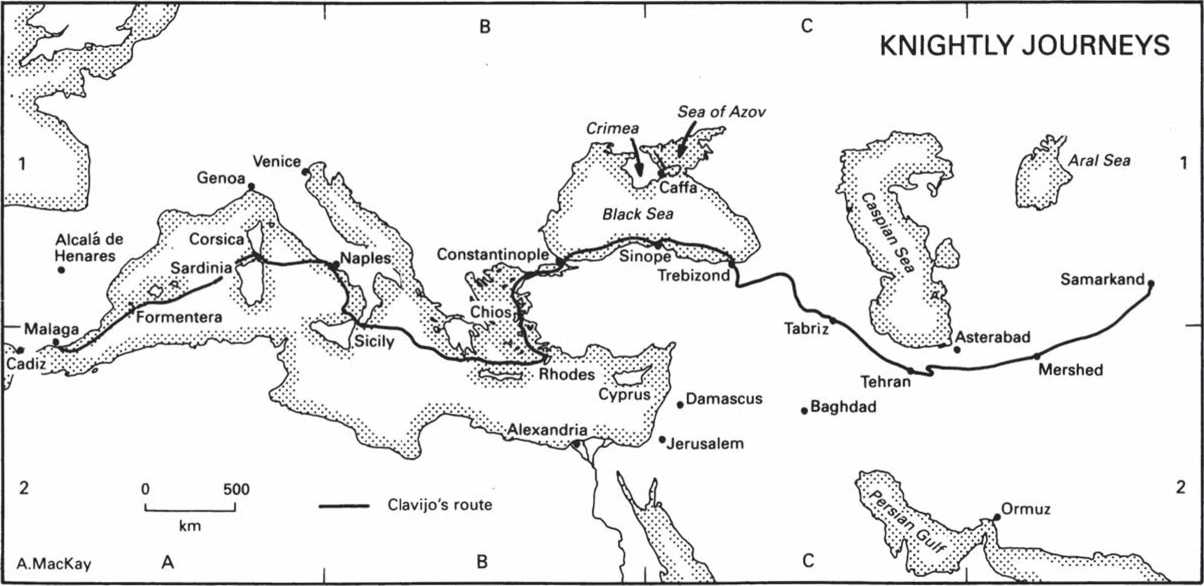

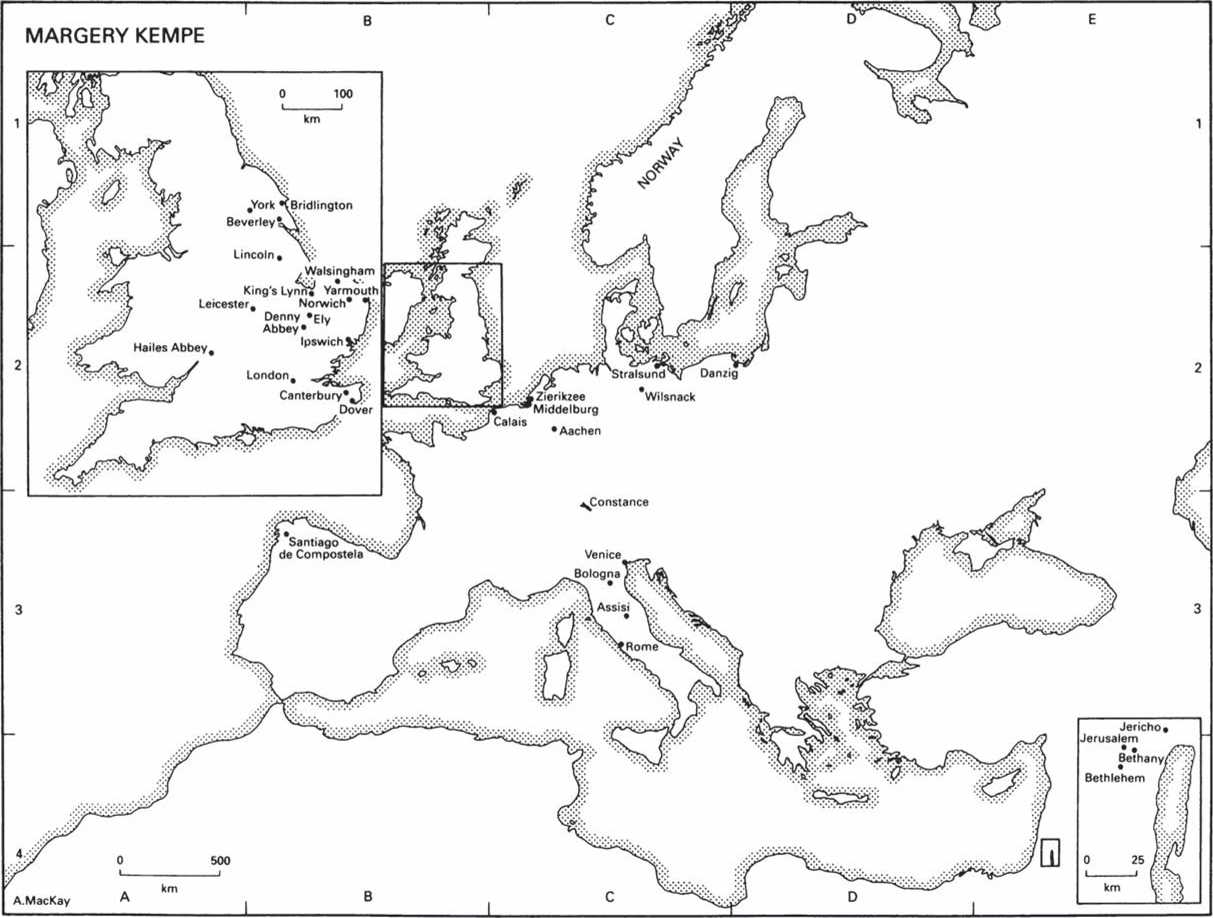

Born c. 1373 in the prosperous port of King's Lynn, the daughter of John Brunham, a substantial oligarch who was several times mayor of the town and one of its Members of Parliament, Margery at the age of 20 married John Kempe. However she seems to have spent most of her subsequent life travelling, motivated by a religious wanderlust that usually took the form of frequent and incessant pilgrimages: to

Jerusalem and the Holy Land, northern Italy, Santiago de Compostela, Norway, northern Germany, and places in England such as York, Walsingham and Leicester. On her travels she left her husband behind, although on occasion at least she was asked whether she had his written permission to journey alone in this way. Probably illiterate, yet with a sound knowledge of some of the scriptures, she began to dictate her

Experiences to a sympathetic priest round about 1436. What emerges from her Book or Life is hardly a traveller's account as one might imagine today; rather it is the description of a succession of emotionally charged religious experiences frequently associated with the places she visited.

When she visited Jerusalem, for example, she arrived there, like Christ, on a donkey. Then at Calvary she had a vision of Christ: not Christ as God but Christ as Man, a suffering human covered in blood, brutally nailed to the Cross. Such visions may well have been influenced by the Franciscan spirituality of the period, but in the view of most of her contemporaries Margery took matters to extremes, particularly since her ecstatic experiences usually took the form of noisy and prolonged bouts of crying, sobbing and roaring, frequently taking place in church and in public. When travelling, her fellow-pilgrims, determined to combine their religious duties with the enjoyment of pleasant company, food and good wine, clearly found her abstemious excesses and constant discoursing on spiritual matters intolerable.

Although Margery's Book does not obviously refer to her experiences in modern terms, the evidence does suggest that she may have suffered from some form of post-natal depression after the birth of her first child (by the time she was 40 she had given birth to fourteen children). Yet in some ways her actions were almost logical. For example, as an avid and frequent partaker of the Eucharist (literally the body and flesh of Christ) she compensated for this excess by becoming a vegetarian. She also had the ability to disturb members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, powerful and humble alike. No stranger to sexual temptation herself, as she recounts vividly, she once turned the tables on a monk by telling him that he had sinned with women, only to be asked by her unfortunate and puzzled victim whether she knew if the women in question were married or single.

Eccentric to a degree and even suspected of being a Lollard, Margery was not perhaps entirely untypical. The number of documented female religious visionaries increased sharply during the later medieval and early modern period. Indeed Margery herself was aware of some of them. She visited the famous anchorite Julian of Norwich, went in Rome to the premises where St Bridget of Sweden had died, and may even have modelled herself to some extent on the Brabantine beguine Mary of Oignes (d. 1213) who also sobbed uncontrollably, persuaded her husband to live chastely, had the gift of visions and prophecies, and was devoted to the Eucharist and Christ's Passion.

A. MacKay

World History

World History