. The term usually used to refer to art produced by and for the “new peoples,” primarily Germanic, who entered the former territory of the Roman Empire as federate allies, mercenaries, raiders, and ultimately as settlers. In France, the migration of new peoples on a large scale is a phenomenon primarily of the 5th century, prior to the establishment of dominant Frankish power throughout most of the country, and the conversion of the Franks to Christianity, ca. 500. By convention, however, “migrations art” refers to ornamental metalwork primarily of non-Christian function and subject matter down to the 7th century. Furthermore, it has become clear that this migrations art is by no means a collection of tribal artistic traditions but rather the product of considerable interchange among Germanic peoples and between the new settlers and indigenous inhabitants; migrations art was not brought to the former Roman territories by new settlers but created there.

The bulk of the migrations art consists of weapons and objects of personal adornment, such as pins, brooches, and buckles, which have been recovered in vast numbers from graves of the period. Important artistic work must also have been undertaken in building (such as royal and aristocratic halls), in wood sculpture, and especially in textiles; that the medium of metalwork alone has survived in quantity gives it undue importance. In addition, the concentration upon elaborate metalwork does not indicate that only portable arts were produced because the artists and their patrons were nomadic. Nonetheless, this metalwork is characteristic of the period, and the great luxury objects played a major role in displaying social patterns and status. Archaeologists and art historians have organized the metalwork of the 5th to early 7th centuries according to technical and stylistic criteria and have concentrated attention on the objects using gold and jewels rather than the far more numerous examples in iron and bronze. Most objects fall within the categories known as chip carving, Polychrome Style, Style I, and Style II. All of these terms are used for objects produced and found from Scandinavia to Italy and from Spain to the Black Sea basin, and for none of them does France appear to have been the most original or productive center, although it certainly participated actively in the development.

Chip carving developed along the eastern borders of the Roman Empire, including the Frankish regions of the lower Rhine, in the late 4th century, in connection with cast-bronze objects made for soldiers; it involved handchiseling of abstract patterns into the metal. The starting point of the tradition is Roman in both design and tech-

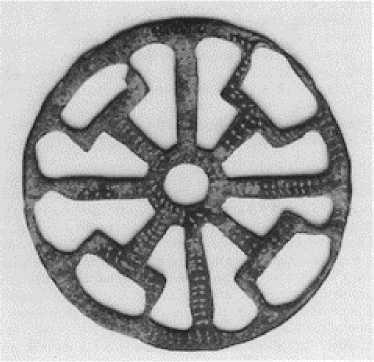

Bronze openwork disk. 500-600 A. D. Northern France. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. P.Morgan, 1917. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pinned bronze buckle and plaque. 525600 A. D. Paris basin. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. P.Morgan, 1917. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Nique, and the bulk of the material, executed in base metals, was used widely throughout the military class. In contrast, the Polychrome Style, developed in eastern Europe by the 4th century, used red garnets, glass, and other colored gems set onto gilt backgrounds as small separate cells, or cloisons, often surrounded with gold granulation and filigree. Patterns are primarily abstract or geometric, and the emphasis on precious materials ensures that this class of objects has royal and aristocratic associations. The greatest French examples of this technique are the sword fittings and other objects from the tomb of Clovis’s father, Childeric I, last pagan Frankish king, a tomb excavated at Tournai in 1653 and usually dated to 481. Here, the color is restricted to the red garnets, now set closely together to make whole fields of red divided only by thin sheets of gold. This polychrome cloisonne style continued well into the 6th century in such luxury objects as the disc brooches founded in the tomb of the Christian Queen Arnegund (probably died ca. 565) excavated in the church of Saint-Denis.

Style I and Style II metalwork focuses upon animal forms. Style I clearly developed in northern Europe, perhaps in Scandinavia and England, in the early 6th century and spread rapidly across France and the Continent. It primarily used compact animals and animal parts, which were treated in a progressively more abstract and decorative manner. Style II now seems likely to have developed in Lombard Italy in the late 6th century, whence it rapidly spread northward into Germany and France. It essentially involves the combination of animal forms with complex ribbon-interlace patterns of Mediterranean origin. Both animal styles were used not only in the decoration of commonplace objects in base metals but also in combination with polychrome cloisonne techniques in a series of objects of stunningly inventive virtuosity, examples of which are again provided from Arnegund’s burial. Ultimately, such decorative styles were adopted for Christian art in reliquaries and other sacred objects of high status.

Lawrence Nees

Gold disk fibula. First half of 7th century. From Neiderbreisig. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. P.Morgan, 1917. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[See also: JEWELRY AND METALWORKING; MEROVINGIAN ART]

Haseloff, Gunther.“Salin’s Style I.” Medieval Archaeology 18 (1974):1-15.

Lasko, Peter. The Kingdom ofthe Franks: Northwest Europe Before Charlemagne. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.

Nees, Lawrence. Justinian to Charlemagne: European Art, 565-787: An Annotated Bibliography. Boston: Hall, 1985.

Perin, Patrick, and Laure-Charlotte Feffer. Les Frances. Paris: Colin, 1987.

Roth, Helmut. Kunst der Volkerwanderungszeit. Supplement-band 4 of Propylaen Kunstgeschichte. Frankfurt am Main: Propylaen, 1979.

World History

World History