This situation soon changed. In the early 830s the Viking raiders started altering their tactics in ominous ways. First, the number of yearly attacks increased markedly. So did the size of the raiding parties, as many Viking fleets grew in size to as many as thirty to thirty-five ships, and in the decades

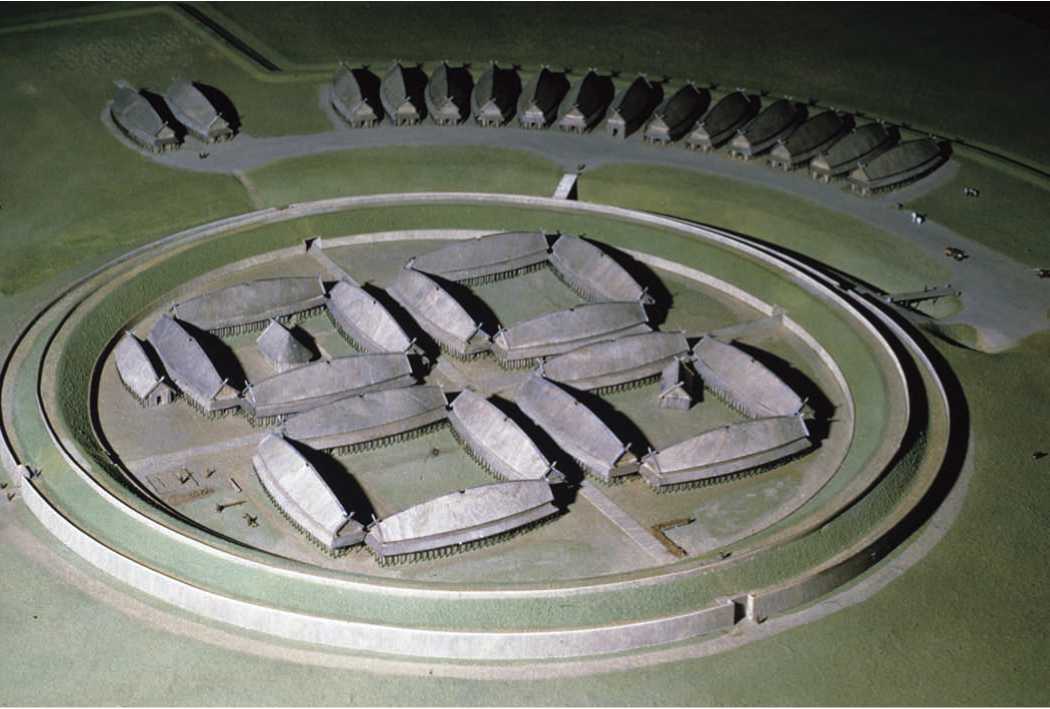

This modern reconstruction shows the Viking longphort, or fortified coastal base, on the island of Zealand, in medieval Denmark.

That followed a few had as many as a hundred vessels.

Even more disconcerting for the victims, the raiders' ships began sailing far upstream on the larger, navigable rivers, which allowed them to ravage inland areas. In Ireland in 836, for instance, a Viking fleet moved up the Shannon River and sacked the important monastery at Clonmacnoise, in the island's heartland. Similar forays were launched up the Rhine River in Germany and the Loire and Seine rivers in France.

Next, in the late 830s and early 840s, many Viking raiders ceased returning to Scandinavia each winter. Instead, they built longphorts, fortified coastal bases, on the shores of Germany and France and later Ireland and Scotland. Raiding parties spent the winter at such bases, allowing them to get an earlier and easier Start in the next raiding season. The tremendous advantage this gave the Vikings can be seen by what happened when such overwintering began in England in 850 or 851. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that "The heathens now for the first time remained over winter in the Isle of Thanet." Thanet is located near the tip of Kent, in southeastern England, a strategic spot where the raiders were able to take the time to amass a huge force for their coming campaign. According to the Chronicle: "The same year came three hundred and fifty ships into the mouth of the Thames [River]; the crew of which went upon land, and stormed Canterbury and London, putting to flight Bertulf [a local king], with his army, and then marched southward over the Thames into Surrey [to conduct more raids]."22

Most disquieting of all was when large Viking groups decided to forego ordinary raiding and pursue large-scale conquest and settlement. This happened in many parts of western Europe, most noticeably at first in southeastern England. In 865, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded, the Viking forces wintering at Thanet "made peace with the men of Kent, who promised money." Paying such money, essentially a bribe to guarantee that the intruders would not pillage the countryside, was becoming a common tactic among the Vikings' victims. The English called it "Danegold," a reference to the fact that many of the raiders were Danes. In any case, the Vikings took the money and then double-crossed the "men of Kent." The Chronicle tells how "under the security of peace, and the promise of money, the [Viking] army in the night stole up the country, and overran all Kent eastward."23 In the years that followed, more and more English and other European lands fell to the invaders.

Modern scholars have frequently debated about why some Vikings resorted to the conquest and settlement of foreign lands. Those scholars generally agree that it was not because the small amount of decent farmland in Scandinavia could no longer support the growing population. Instead, such conquests appear to have been a way for some of the more determined and competing Viking leaders to create their own power bases outside the homelands. As Hall points out, the conquered lands

Were arenas where ambitious and successful warriors with only a relatively low social standing in their homeland could escape those constraints, dramatically improve their fortunes, and become their own masters. The careers of some leaders suggest that they were not mere opportunists, but were prepared to assault target after target in dogged pursuit of a territory over which they could exert control.24

World History

World History