Although the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan died while campaigning against the Karakhanid emirs east of the Caspian soon after his

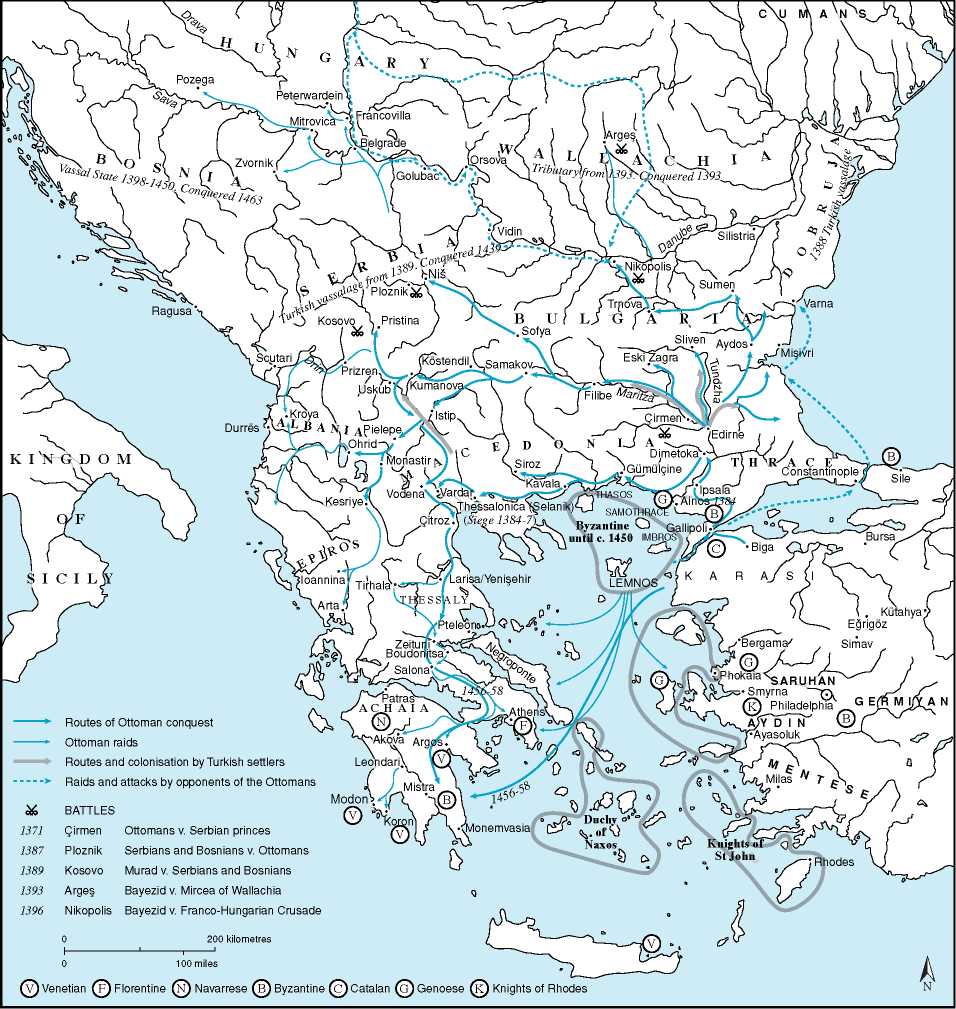

Map 11.3 Byzantium’s Balkan neighbours 1350-1453: Serbs, Bulgars and Turks. (After Kennedy, Historical Atlas of Islam.)

Victory at Manzikert, the Byzantine civil war enabled a rapid Turkish occupation of the central Anatolian plateau, much of it well suited to the pastoral nomadic lifestyle. By the 1090s, however, the Sultanate had split into three major parts, the sultanates of Merv, in the east, of Hamadan (Iran, Iraq and parts of Syria) in the centre, and of Nicaea (Iznik) in the west. The latter ruled over the greater part of the lands conquered from the Byzantine empire, although the Danishmend clan which actually controlled much of the eastern and central plateau regions barely accepted the sultan’s authority. The arrival

Of the First Crusade effectively returned Nicaea to imperial authority, along with substantial districts around it, and made the Danishmendid emirate independent of Seljuk authority. The Seljuks, meanwhile, had withdrawn onto the plateau and established a new capital at the formerly Byzantine fortress town of Ikonion (Konya). To the east of the Danishmendid emirs the emirate of Armenia owed nominal fealty to the Seljuk sultans of Hamadan, as did their neighbours to the south, the emirs of Mosul. In practice, both were more or less entirely independent, along with a number of other petty emirs along the frontier, a factor which gave the advancing First Crusade a decided advantage in the campaign which led to their capture of Jerusalem in 1099.

By the 1150s the sultanate of Konya was the most powerful of the Seljuk states in Asia Minor, but had to contend with alliances or agreements between its neighbours to both east - the Danishmendid emirate and other minor factions - and west - the Byzantines. It faced its greatest threat in the 1170s when the Emperor Manuel I, having first isolated it diplomatically from its neighbours, set out in 1176 with the intention of capturing Ikonion and destroying the Seljuk power base. But the campaign failed. By the early thirteenth century the easterly emirates had been absorbed and the sultan at Konya ruled the whole of central and eastern Asia Minor. The westernmost parts of the empire of Trebizond fell to Seljuk forces in 1214, which gave them access to the Black Sea. Yet within a few years these advances were checked by the arrival of a substantial Mongol reconnaissance and raiding force (1221), which disrupted the political situation in the Caucasus region. In the wake of this, the Seljuks were forced to make common cause with the Ayyubids to the south to resist the expansion into this region of the revived Shahdom of Khwarizm, which had itself been defeated by the first Mongol attacks but was able to recover for a short period. Yet by 1243 a second Mongol attack had destroyed the Khwarizmian shahdom, conquered previously independent Christian Georgia, and made the Seljuks tributary.

From the 1230s there took place a movement into Anatolia of a number of Turkmen nomadic groups displaced by the Mongols further to the east. These troublesome groups were despatched to the Byzantine frontier regions where, led by their ug beys, marcher lords, they waged jihad against the Christian forces to west and north. They also exacerbated the internal political problems of the sultans of Rum, and in 1241 a major revolt had to be crushed by the sultan Kay Kusrau II (12411246). The Mongol attack of1246 promoted the breakdown of central Seljuk power, however. Konya continued as the centre of one sultanate, while another was established under Mongol suzerainty at Sebasteia (Sivas). Although temporarily reunited under the sultan of Sivas until 1277 (when the Mongol Ilkhan of Iran crushed the Seljuk forces), between 1280 and 1320 the tributary sultanate broke up into a number of competing factions dominated by the ug beys. The most significant were the Karamanids in central and southern Anatolia (who took Konya in 1308 but were expelled by the Mongols); but the emirate of Kastamonu to the west of Trebizond and the confederation of the six emirates in the south-west competed from the early fourteenth century on equal terms until the rise of the Osmanli beys - the Ottomans - began to bring about substantial changes.

Although hemmed into the north-western provinces of Asia Minor, the Ottomans had the advantage of facing a Christian enemy, in the shape of the Byzantines, and of being able to exploit the situation in the Balkans when Byzantine emperors requested military aid from them. By the 1360s entrenched in Gallipoli and by the 1390s the dominant Balkan power, this provided the Ottomans with reserves of wealth and manpower which makes their eventual conquest of the independent Anatolian emirates readily understandable. Between 1390 and 1393 Bayezid I had defeated and absorbed these territories into his realm and extended the frontier of his power to the Euphrates. Unfortunately, this success was short-lived: the invasion of Timur in 1402 resulted in a crushing defeat for the Ottomans, and the re-establishment of the independence of the subject emirs. Yet in spite of a revival of Christian power in the Balkans and the emergence of revived emirates of Karaman and Kastamonu, Bayezid’s successor Mehmet I was quickly able to restore Ottoman pre-eminence. By 1430 the situation before the battle of Ankara was almost restored. Only in eastern Asia Minor did the Ottoman sultan face a more substantial problem.

At the same period as the Osmanli power was developing to the west, two other powerful Turkmen emirates had evolved from the collapsing Ilkhanate of Persia. The White Sheep Turks (Akkoyunlu) in eastern Asia Minor (up to the Euphrates) and the Black Sheep Turks (Karakoyunlu) in Iran and Iraq, represented two powerful warring confederacies. The Ilkhanate itself, Islamised in 1300 and the following years, having lost control over Anatolia and the Turks, had fragmented even further by the 1330s, with the central section ruled by the Jalayrids, and a number of emirates in the eastern regions. Temporarily weakened by Timur’s invasion, the Karakoyunlu were for a while able to expand southwards into southern Iraq at the expense of the Jalayrids, but were eventually defeated and absorbed by the White Sheep (who had sided with Timur and benefited therefrom) in 1467. By 1502, the rise of the Safavid Persian empire and the expansion of the Ottomans eastwards brought the Akkoyunlu emirate to an end in the first years of the sixteenth century. The only Christian power to survive in the east (apart from the Lusignan kingdom of Cyprus, taken eventually by the Mamluks in 1426) was the kingdom of Georgia, relatively safe, but also isolated, in the Caucasus and eastern Pontic plain.

World History

World History